Inside the American Museum of Natural History’s Hidden Masterpiece

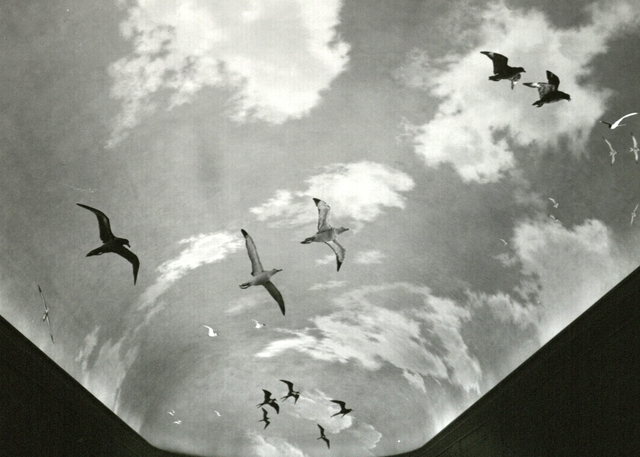

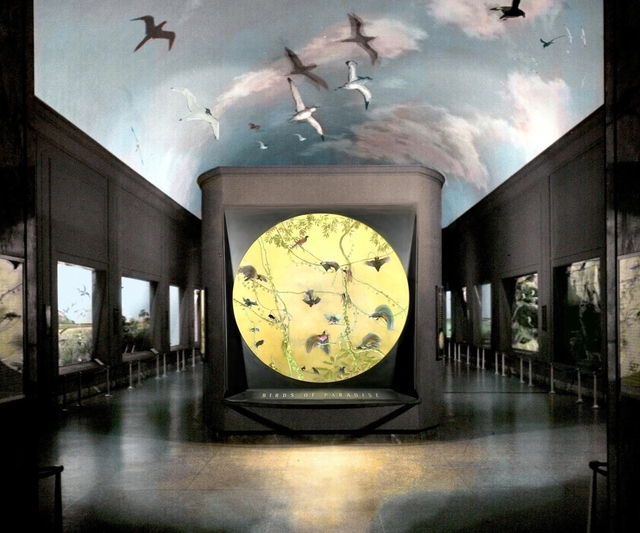

The Whitney Hall of Oceanic Birds at its official dedication in 1953. American Museum of Natural History (AMNH) Photograph #319645

Visitors to the American Museum of Natural History’s popular Butterfly Conservatory could be forgiven a moment’s confusion when they enter the exhibit through an archway marked ‘Birds of the Pacific.’ A framed mayoral proclamation, signed by Ed Koch in 1989, hangs on the wall by the entrance. It commemorates the fiftieth anniversary of the museum’s Whitney Wing “and its two public exhibitions, the Whitney Hall of Oceanic Birds and the Sanford Hall of Bird Life, which have enlightened millions of students, scholars, and visitors from around the world and will continue to be sources of knowledge and enjoyment for generations to come.”

Neither hall, however, really exists any more. The Sanford hall was dismantled in 1999 to make room for an expansion of the planetarium, and the Whitney hall’s fate is ambiguous: like an abandoned subway station, it can be glimpsed, but is mostly hidden. Ten of its eighteen dioramas are concealed behind the conservatory’s cocoon-shaped enclosure, where live tropical butterflies land on visitors’ heads and outstretched fingers.

The Whitney hall was once one of the crown jewels of the museum, alongside the halls of African and North American mammals, and like them it was a reminder of a time when the museum pushed the boundaries of dioramas as educational objects and as art. Over the years, even as range maps and species names have become outdated, the art has remained potent; the mammal halls’ dioramas retain an eerie, sublime power. At their best they seem deeply and strangely alive. The Hall of North American Mammals was lovingly restored and reopened in 2012, and the numinous indoor courtyard of the African hall, whose dark-paneled galleries surround a parading family of elephants, remains the museum’s literal and figurative centerpiece. But of the three halls, the Whitney might have been the most ambitious, if not quite in grandeur, then at least in scope. Oceanic birds were its alleged focus, but its true aim was to create “the Pacific in microcosm,” cramming the landscapes, seascapes, and feathered wildlife of nearly half the globe—all Oceania—into one room.

The hall was the brainchild of Frank Chapman, the visionary chairman of the museum’s Department of Ornithology, and Leonard C. Sanford, a deep-pocketed New Haven surgeon with an ornithology habit. Chapman arrived at the museum as a volunteer in 1887 and didn’t retire until 1942, at age 78. He more or less acquired Sanford along the way: in 1912, Chapman convinced him to store his personal collection of bird skins at the museum and installed him in an office next to Chapman’s as an unofficial member of the staff.

It was a shrewd, if unconventional, move. Sanford was well-connected, ambitious, persuasive, and competitive, especially with his friends at Harvard’s Museum of Comparative Zoology. Robert Cushman Murphy, who came to the museum as a young man in 1912 and later chaired the department after Chapman retired, noted that Sanford “particularly enjoyed possessing things which the other fellow did not have, and partly because the other fellow did not have them.”

Sanford’s new position let him scratch this itch in ways he could only have imagined as a private collector. He was especially keen to send collecting expeditions to poorly-surveyed parts of the world, and he had a gift for convincing his well-heeled friends to share his enthusiasm. It was a golden age for field ornithology; steamships, railroads, and the fledgling automobile had made the world newly accessible, but vast regions remained unsurveyed. Sanford’s first major effort was a marine expedition to collect shorebirds and seabirds around the coast of South America, a huge job that would take years to complete. After persuading a museum trustee to help fund the project, Sanford hired an unusually gifted Californian bird collector named Rollo Beck to see it through.

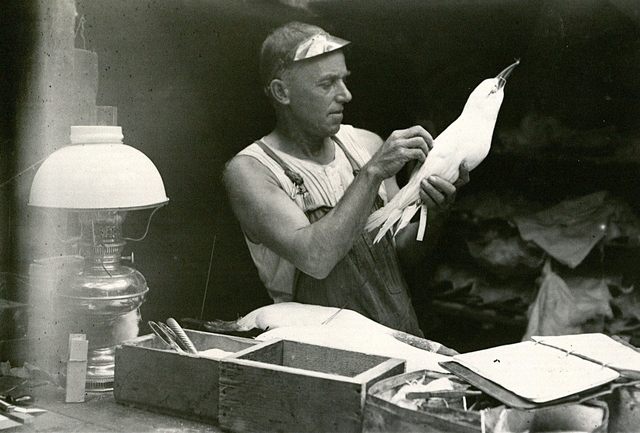

Rollo Beck preparing the skin of a tropicbird aboard the France on the Whitney South Seas Expedition. AMNH Photo #107954

Beck was one of a kind. He only had an eighth-grade education, but he was hardy, brilliant, and brave—a “tough little bastard,” as a friend described him, who could spend days in a skiff or rowboat alone at sea collecting birds, skinning them, and living off the meat of their carcasses. He pioneered the technique of “chumming” for seabirds, tossing oily bits of meat and offal from the boat as he drifted with the current, then rowing back and picking off the birds that collected to scavenge on the slick. This technique amazed Beck’s companions, who couldn’t understand how he could so confidently set out to bag seabirds where there weren’t any to be seen, but he knew from experience that seabirds can detect food from miles away just as turkey vultures do on land – with a keen sense of smell. Beck’s wife, Ida, who often accompanied him on collecting trips, sometimes waited for him on the shores of Monterey Bay until well after dark.

The Becks–adventuresome, childless, and equally handy with a scalpel and a shotgun—seemed tailor-made for Sanford’s South American expedition. With his backing, they spent the years from 1912 to 1917 circumnavigating the coast of the continent, returning to the United States via the West Indies. The thousands of specimens they collected surpassed the museum’s expectations—Murphy, who used them as his primary reference for his landmark Oceanic Birds of South America, gushed that “no other ornithological collector has carried through a similar campaign, or matched such scientific spoils.”

Rollo and Ida, for their part, seemed to have enjoyed the challenge. A photograph of them on Christmas Day, 1914, aboard the small sailboat Legúri, shows them looking weathered but sturdy and good-humored as they prepare “Christmas dinner” among the fjords and islands of southern Chile. They seem to be sharing a private joke with the photographer; Ida smiles warmly and Rollo, wearing an impish expression, looms like a Cheshire Cat out of the darkness of the hold to her left. Another image from the same day, taken by Rollo, shows a gracefully posed Ida reading The Ladies’ Home Journal on deck with a young gentoo penguin by her side. Three days later, Ida appears perched on a cliff, gazing toward the famous silhouette of Cape Horn. It looks like a good place to be in the second year of the First World War.

Buoyed by the South American expedition’s success, Sanford decided to set his sights on an ornithological holy grail. He wanted to send the Becks on another multi-year collecting trip, this time to the far-flung islands of the South Pacific.

The Pacific islands were both known and rumored to be the home of many rare and undescribed birds—jewel-like honeyeaters and sunbirds; the collected-once-and-never-seen-again Meek’s Pigeon; the leggy, flightless Kagu of New Caledonia—but Sanford wasn’t only interested in trophies and bragging rights. Like his friend Walter Rothschild in England, Sanford wanted a complete “series” of bird skins from each island, even where species were duplicated, to create a picture not only of what birds existed in the world, but exactly where they were, reflecting a growing scientific interest in small geographical variations among related species. Nowhere were these variations more pronounced than among island birds, and nowhere were there more islands than in the Pacific—some twenty to thirty thousand—many of them never surveyed by ornithologists. Sanford wasn’t deterred by the fact that these islands were spread over an area almost as large as all the world’s land masses combined.

Finding the money for such a wildly ambitious project, however, was another matter. Sanford eventually coaxed it from Harry Payne Whitney, husband of Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney (who later endowed the Whitney Museum of American Art). Whitney contributed $100,000, which provided for the purchase of a battered-but-sturdy schooner, the France, and funded its operation for five years. The Becks set sail for Fiji in 1920, launching the Whitney South Seas Expedition–an unprecedented collecting effort that ultimately stayed in the field for the next two decades.

Life aboard the France was trying. The ship’s engine was unreliable at best, and it was so hot and cramped in the cabin that everyone usually slept on deck, where they were often drenched by night rains. The crew endured dengue fever, malaria and dysentery, and choked down a monotonous diet of rice and tinned salmon. They also contended with an infestation of cockroaches and the smells of what was basically a floating abattoir. “It was not,” one participant recalled, “a glorious expedition in any sense of the word.” Added to all this was the danger of visiting islands whose residents might not welcome strange foreigners. En route to a notorious island near New Ireland, an official of the then-British territorial authority gave the bird collectors a fifty-fifty chance of making it back alive.

Nevertheless, the expedition was an unqualified success, and the Becks’ casual photographs of the birds and people of the south seas suggest a world that was unfamiliar but not unfriendly. After five years, the France hadn’t even left the many islands of Fiji, but the Becks’ steady pace and remarkable skill resulted in a comprehensive collection, enabling Sanford to secure continued funding from the Whitneys. (The Becks, possibly out of exasperation with the Ivy League boys the museum kept sending them as field assistants, left the expedition after nine years and traveled on their own to Australia and New Guinea, where Rollo discovered a new species of bowerbird.)

In 1929, Sanford went back to the Whitneys again, not only for more money for the South Seas Expedition, but with something even grander and pricier in mind. Birds were pouring into the Department of Ornithology from the Pacific and from separate expeditions to the interiors of Africa and South America, and a new facility was urgently needed to keep the specimens safe from fire, rot, and vermin. Sanford asked the Whitneys to fund the construction of an entire new wing of the museum, purpose-built to house and display its overflowing bird collection. The wing would also include two permanent exhibit halls, one of which would showcase the birds of the Whitney expedition and their home islands, bringing the distant worlds of the Pacific—previously known best to the public from the works of Gauguin and Melville—to Manhattan.

The Whitneys, once again, capitulated. They gave an enormous sum of stock to the project, the city provided matching funds, and the museum broke ground on the Whitney Wing in 1931. The South Seas Expedition, having expanded its geographical scope as far as New Zealand and the Marianas, now added a new dimension to its mission: to bring back not only island birds, but the islands themselves.

Frank Chapman was ahead of his time in his belief that museum displays should present animals in the context of their habitats, and insisted that dioramas should depict actual places, not idealized composites. To prepare for the construction of an exhibit hall devoted to Pacific birds, the museum hired plant collectors and photographers for foreground material and visual artists charged with absorbing the colors, textures, and moods of the Pacific islands for the backgrounds of the Whitney hall’s exhibits.

Francis Lee Jaques, a gifted painter of birds in flight who conceived the eighteen-window design of the hall, accompanied the Whitney expedition to eastern Polynesia and in 1936 was selected for the career-defining job of painting all of the hall’s dioramas. In hiring a single artist for this massive endeavor, Chapman and Sanford hoped to produce a feeling of unity and coherence among the disparate landscapes.

Jaques’ career wasn’t the only one shaped by the expedition. Among its alumni was an energetic young German ornithologist named Ernst Mayr, who left an isolated field camp in New Guinea to join the crew of the France in 1930. In 1931, Mayr accepted a post at the museum, where he began the mammoth job of describing and analyzing its growing backlog of bird skins. Many of the specimens were new to science, and Mayr drew on the incredible breadth of the expedition’s collection and his own field experiences as the basis for his still-definitive list of the birds of New Guinea and his landmark Systematics and the Origin of Species (1942), which essentially created the modern field of evolutionary biology.

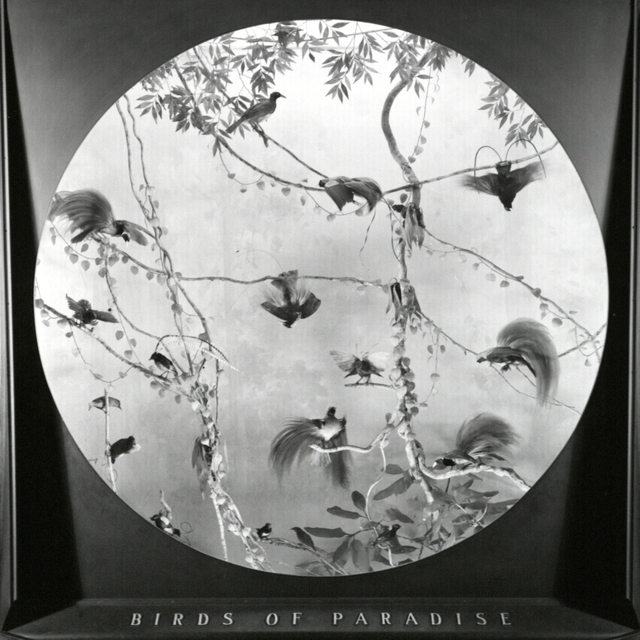

It’s probably fair to say that the birds collected by the Whitney expedition were as significant for Mayr, and for science itself, as the birds of the Galapagos were for Darwin. As the Hall of Oceanic Birds took shape, Mayr must have seen it as a monument to a part of the world to which he owed a great debt. It probably pleased him when Murphy’s staff installed a medallion-shaped display of the outlandishly decorated New Guinean crow relatives dearest to Mayr’s heart, the birds of paradise, facing visitors as they entered the Whitney hall.

Thirty-two years elapsed between the launch of the France and the final stroke of Jaques’ brush on the dioramas of the Hall of Oceanic Birds, which now contained mounted specimens of more than 400 species, some of which could be seen nowhere else outside of their home islands, and several of which had rarely been seen at all.

It was 1952. The South Seas Expedition had continued under different leaders until the outbreak of World War II, when many of the islands visited by the bird collectors became scenes of heavy fighting. The war delayed work on the hall itself for several years, but it also gave the far reaches of the Pacific an immediacy and interest for Americans that Sanford couldn’t have anticipated in 1920. Jaques had already officially retired, and Mayr, who would become one of the most revered biologists of the twentieth century, would soon move on to a new position at Harvard. Leonard Sanford, Frank Chapman, Rollo Beck, and Harry Payne Whitney had died.

But their vision was realized. From the center of the hall, visitors were surrounded by a unified, 360-degree panorama with a consistent horizon that embraced every Pacific landscape, from coral atolls to volcanic peaks, from the high seas to sub-Antarctic forests. In the domed ceiling above, painted like the sky, soared delicate snow petrels, giant albatrosses, and blade-winged tropical frigatebirds. At the hall’s dedication in January 1953, Whitney’s son Cornelius declared:

Here tonight we may all feel privileged to observe a dream come true…there is sweat, toil, and tears represented here. There is success and failure. There is devotion to science, loyalty to friends, and high romance. There is a past, a present, and a future. There is a corner of knowledge added to the mysteries of the universe in which we live. There is a thing of beauty, and so, of truth.

“It was incredible,” said Peter Capainolo, scientific assistant for ornithology at the museum, closing the brass gate of the Whitney Wing’s original freight elevator. “It was like you were there.” Capainolo, balding and soft-spoken with a gray mustache and a convivial Long Island accent, has worked in the department for over a decade and is especially fond of birds of prey. A very convincing golden eagle, rescued from an eddy of the collection, perches on a filing cabinet in his office.

He pulled a lever, and the elevator descended from the offices of the Department of Ornithology to the basement of the Whitney Wing, past the halls built to contain and showcase the museum’s vast bird holdings, which long ago left Harvard’s in the dust. New acquisitions have slowed to a trickle, but the wing now holds nearly a million specimens—skins, skeletons, and whole birds in formalin gathered from every part of the living world at immense cost and effort over many decades.

Most of them remain stored in metal cabinets, laid side by side in long trays. Capainolo led the way into the lab where study skins are still occasionally prepared; a female turkey he’d shot upstate a few days earlier was pinned out to dry on a table. The turkey was one of about 250 skins Capainolo has contributed to the collection over the course of his career. Rollo Beck, at the museum’s last count, supplied at least 44,000.

Two floors up, the elevator’s doors opened to admit a blast of warm, humid air pumped from the butterfly exhibit’s ventilation system. Capainolo smiled at a surprised guard resting in a folding chair and opened a door into the corner office of Ben King, the museum’s partly-retired expert on Southeast Asian birds. King wasn’t in. The office was like a time capsule from an earlier age of the museum, spacious but cluttered, piled with books, maps, bones, every volume of the immense Handbook of Birds of the World, and, against one wall, a Victorian-era collection of miscellaneous North American birds in a dusty glass case.

The birds in the case were arranged like flowers on a stylized tangle of branches and vines. It was an undeniably beautiful object, but more whimsy than science, and Capainolo noted the presence of a European starling – a recent introduction to the continent at the time the case was built. “That’s how they used to do it,” he said. “Lots of pretty birds.” He opened another small door in the far wall of the office and stepped through it into a dim, narrow, high-ceilinged passage that ran the length of the Whitney hall.

Inside the passage, nine metal-ribbed half-silos stretched from floor to ceiling, like columns of a massive temple: these were the curved backs of the hidden dioramas, sealed in the dark for the past fifteen years. To preserve the illusion of their seamless backgrounds, there were no secret doors; access was only through the glass in front, covered over now with plywood. Hidden inside were the landscapes and birds of Fiji, Papua, the snowy peaks of western New Guinea, wind-blasted Little Diomede (a tiny spot of land in the Bering Sea), and the shores of the Great Barrier Reef. Piles of cardboard boxes choked the corridor, an antique Underwood typewriter rested against the wall, and a decades-old can of Schaefer beer was tucked behind a railing. Capainolo nodded toward a ladder that ascended into darkness near the doorway. “There’s a little platform up there that’d be a good place to take a nap,” he said. “You go up there, nobody’ll find you.”

On a recent afternoon in the Butterfly Conservatory, a museum volunteer armed with a spray bottle misted the branches of potted Norfolk Island pines, and a family from Pittsburgh admired a trio of resting monarchs. These butterflies, explained the guide, were imported as pupae from farms where they were specially raised for exhibits like this one. They’re also the stars, he added, of the film on butterfly migration showing downstairs in the IMAX theatre. The monarchs, their folded underwings the pale brown of dead leaves, were North American, but their cellmates were cosmopolitan: bouncing against the lights or uncurling their tongues to drink condensation from the walls, they hailed from the Amazon, East Africa, Malaysia. Rows of unhatched chrysalides in a narrow glass box bulged and twitched, and a towheaded little girl contemplated a female swallowtail flopping in a plate of orange slices, its wings grown ragged in the final hours of its few weeks of life.

The Butterfly Conservatory, sponsored by Lord & Taylor, was installed in 1998 as a temporary exhibit—the Whitney hall had been meticulously cleaned, and its signage updated—but the butterflies’ popularity has endured. Visitors paying a special exhibition fee are allowed in every half hour, and on most days between October and June a steady stream of people files out of the conservatory’s double doors past four of the still-visible dioramas of the Hall of Oceanic Birds: tropical Samoa, the wild seas of the high southern latitudes, the Snares Islands, and New Zealand. Though the most colorful birds are slightly faded after sixty years on display, the scenes remain remarkably fresh and real: Samoa’s lorikeets, honey-eaters and fruit-doves blithely perch in view of a concealed barn owl, the yellow-crested penguins of the Snares nest in a weird forest of tree daisies, and elegant, wave-hugging cape petrels and prions soar over the bow of the France.

New Zealand, however, stands out from the others, as its centerpiece is an elaborate fake. Dominating the scene is a model of a moa, an ostrich-sized grazing bird which no one has seen alive for centuries. It was probably an irresistible temptation to include it for Murphy, who spent time digging up sub-fossil moa bones on New Zealand’s South Island, but it’s an odd moment of scientific nostalgia in a hall so dedicated to preserving the Pacific as it was in the early twentieth century that a bullet-pierced American soldier’s helmet lies in the foreground of the Philippines diorama.

The moa, with its long, curved neck, shaggy feathers, massive feet, and golden eyes, peers out at the viewer from a remote beach among the fjords of the South Island, surrounded by a host of strange birds that are now extremely rare—an enormous, flightless parrot, a crow-like bird with odd blue wattles, a purple-and-green moorhen with a huge red beak. The scene is rendered so lovingly and believably that it elicits a pang of regret, as it seems meant to, that this version of the world is gone, that these giants no longer walk among us.

A sign by the exit reads: “The Whitney Hall of Oceanic Birds is temporarily closed. We apologize for the inconvenience.”

I would like to gratefully acknowledge Michael Walker, Peter Capainolo, Mary LeCroy, Paul Sweet, and Barbara Mathé of the American Museum of Natural History in New York for being so generous with their time and attention, and for granting me “backstage” access to the Whitney hall and its archives. I would also like to thank Branan Edgens for his photographs, and Robin Woods for pointing me toward the remarkable life stories of Rollo and Ida Beck.