“Nancy Grows Up,” the Media Age, and the Historian’s Craft

The Challenge of “Nancy Grows Up”

It begins with anxious crying. The plaintive sound only lasts a few moments before the screams drop into a slightly lower register and transform into a calm murmur. The sound repeats, then breaks into the rudiments of language. It sings—or tries—and falters. A man helps, playing a game with a familiar rhyme: “Jack and Jill went up the … to fetch a pail of … Jack fell down and broke his … and Jill came tumbling …”

She fills in the appropriate words and, as she does, we suddenly meet her.

For the remaining minute and forty-two seconds we hear and follow Nancy. We listen to her development as a person through a variety of situations: she wishes her father a happy birthday, she lists what she wants for Christmas (“a puppy and a whistle and a horn and a hat and a dress and a ballerina costume”), she explains how to housetrain a dog, and she expresses her feelings about the Russians sending the dog Laika into space. All the while Nancy’s voice grows increasingly distinct, speaks longer, takes on and sheds accents, and uses increasingly sophisticated vocabulary. Finally, the recording ends, but it does so just as we witness what seems like a personal milestone. Nancy becomes silent just after we see the door open on her developing sexuality. In the last and longest of the voices, after updating us on what she has been doing at school, she sighs and confesses, “and I’ve been discovering boys.”

“Nancy Grows Up”

Recorded over the course of the 1950s and the early 1960s, “Nancy Grows Up” gives us a beautiful and stimulating portrait of growth. It is an audio montage; Tony Schwartz, its creator, continuously taped his niece from her first month of life to the age of thirteen and, later, spliced together pieces chronologically. Schwartz likened what he did to time-lapse photography: it condenses the story of thirteen years, as Schwartz said, in less than two and a half minutes.

“Nancy Grows Up” is more than a simple novelty piece. Poetic and expository, it reveals a type of storytelling that has an enigmatic intelligibility. Offering a biographical history of development, “Nancy” narrates the phases and stages of a young girl’s early life. It does so quite successfully and evocatively and achieves a rich unspoken analysis in its juxtaposition of different voices, words, and timbre.

Confronted with the possibilities of communication in “Nancy,” one can’t help but ask, “why have historians neglected sound?” Despite more than a century and a half of ongoing media revolutions, historians—especially professional academic historians—have largely worked within a self-imposed textual ghetto. Why have historians restricted themselves to written histories? Why only the monograph and journal article after the advent of the photo essay, the LP record, the radio show, documentary film, and animation short?

There do seem to be substantial reasons for why we have continued to rely almost exclusively on text. It is beyond the scope of this piece to attempt to give a comprehensive explanation of this phenomenon, but a few things come immediately to mind. Text’s capacity to transmit large masses of information, for example, is attractive. The monograph and article also parallel and allow the exact reproduction of what has been most historians’ primary source: written documents. Furthermore, the footnote, the sine qua non of historical scholarship and the linguistic technology for and symbol of the discipline’s seriousness and rigor, appears almost inextricably grounded in the text.

Beginning to rethink the footnote outside the page only seemed possible recently. Internet-based publications have shown that digital footnotes can reference sources in more direct ways, offer more detail and information, and, possibly, shift the function of the footnote altogether. The blog maintained by The Appendix, for example, uses hyperlink footnotes to immediately show the content of a source or acquaint the reader with information about an obscure person or organization.

Text has served historians well, but it is useful to ask if we have missed whole modes of analysis and presentation with such a consistently narrow range of media. How, for example, has the primacy of text and the page shaped how we understand and judge historical scholarship as a whole? Hayden White famously asserted that historical interpretation is shaped by the plot structures of particular kinds of stories—the romance, the tragedy, the comedy, and the satire—but we can go one step further: history as a discipline has also been fundamentally structured by its medium. The way we conceive of the work of history and, thus, the field in which history can be told and debated are intimately intertwined with and determined by the advantages and limitations of the written word.

There is nothing essential linking history and text. Historians can and should embrace other media in the production of history. Fortunately, there are considerable guideposts for a journey into new media; our neglect has not been for a lack of evidence of the unique and intriguing capabilities of other media.

The use and exploration of sound and sound technology offer clear examples of this. “Nancy Grows Up” was not an isolated piece; it was part of a large, rich history of thinking about and through sound in the twentieth century. Even a brief account of sound technology shows that there is a considerable body of work in other media that historians could learn from and draw on.

Looking at some of the ideas and practices surrounding “Nancy” illuminates some of the ways non-historians have sought to engage sound narrative and documentation.

Telling with Sound: A Very Short History

The cover of Tony Schwartz’s 1959 LP, The New York Taxi Driver. Folkways Records

From the late 1920s until the early 1950s, American radio drama, comedies, and soap operas pioneered new ways of conveying stories and ideas through voice and other auditory material. These shows worked out, in the words of radio scholar Susan Douglas, a mode of “story listening.” Although primarily a source of entertainment, Orson Welles’s 1938 famous Mercury Theater production of War of the Worlds—and the consequent panic that a Martian invasion was under way—demonstrates the immense power and effect that audio stories could wield. Welles’s ability to create hysteria and horror in his listeners was a direct consequence of his “media sense”—his talent at adapting storytelling to his artistic vehicle.

Across the pond, intellectuals quickly used the young technology as material for modernist experimentation. During the late 1920s and early 1930s, German artists sought to create a radio-specific art form, i.e., an artistic genre that would reveal and marshal radio’s unique characteristics. The intriguing possibilities of the ether attracted a number of artists from outside the musical or theatrical world; established writers like Alfred Döblin and future film directors like Max Ophüls and Billy Wilder produced Hörbilder (literally, listening pictures) and Hörspiele (listening plays). In 1930, the avant-garde director Walter Ruttmann produced the following:

Walter Ruttmann, Wochenende, (1930)

A film soundtrack without the accompanying picture, Wochenende is the story of a weekend. Ruttmann had spent much of the previous decade making “Absolute Film,” abstract films which attempted to capture the essential qualities of the filmic medium. With Wochenende, he tried to do the same with sound. Working with new sound film technology, he isolated the soundtrack and built a narrative using a montage of noises, identifiable sounds, and speech-fragments.

Germans were not the only Europeans playing with the open possibilities of radio form. Around the same time, Lance Sieveking attempted his own experiments in “wireless imagination” at the BBC and Italian Futurists like Fillipo Marinetti produced music and theater for fascist radio.

Others, like Paul Daharme, Sir Oliver Lodge, and Rudolf Arnheim, wrote and theorized about the possibilities of the disembodied auditory content of radio during the interwar period. For many, the ethereal and mysterious qualities of radio could foster outlandish hopes and fantasies. Daharme and Lodge, for example, believed that the ether granted access to new psychological and metaphysical spaces. Daharme, a French advertiser and experimental radio practitioner, believed that broadcasting could reach directly into the unconscious and radio works could provoke a psychoactive space in which individuals would encounter their own theater of the mind. Lodge, a pioneer in radio technology and revered British scientist, argued that the ether comingled with the realm of the dead and that broadcasting could be used as a spiritualist tool to communicate with lost love ones.

Arnheim stayed a bit closer to the ground. Like Daharme and Lodge, however, he was also fascinated by radio’s ability to detach sound from image. After years thinking about images as a film critic, he wrote Radio: The Art of Sound. In it he pondered the power of isolated sounds and the audio-specific methods through which radio could tell stories.

The ether was not only used for fiction and modernist abstraction, however. Radio journalists also produced documentary news programs. By the late 1930s, broadcast journalism had supplanted newspapers for immediate news coverage in the United States, and most Americans on the home front experienced World War II on a day-to-day basis through listening. Radio journalism employed all sorts of sounds—location noises, sound effects, monologues, and dialogues—in order to move audiences between “informational listening” (taking in facts) and “dimensional listening” (where, for example, “people were compelled to conjure up maps, topographies, street scenes in London after a bombing”).

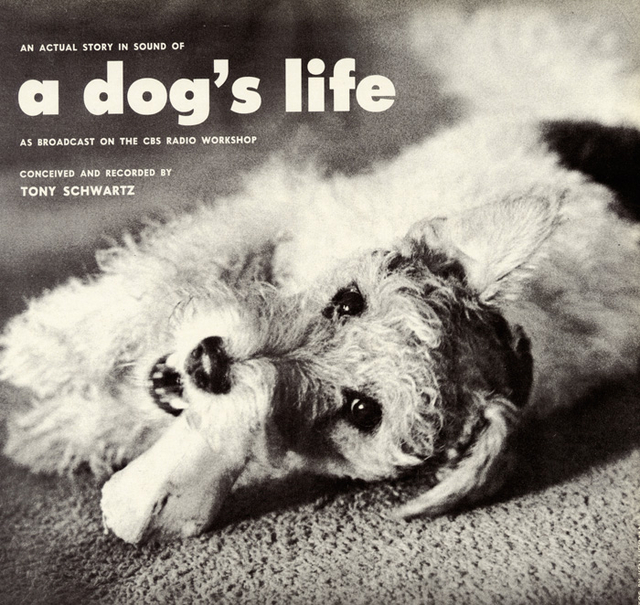

After their introduction in 1948, long playing records provided new materials and resources to explore the story-telling and documentary capabilities of sound. In addition to being repeatable, LPs had a distinct advantage over radio: their multi-faceted presentation format. Record producers and designers could use the non-aural parts of the LP—the label, cover, photos, and liner notes—to guide the listener’s perceptions and stoke their imagination. Ever the brilliant pioneer, Schwartz made a number of innovative narrative and representational experimental recordings for Folkway Records, including An Actual Story in Sound of a Dog’s Life, New York 19, Nueva York: A Tape Documentary of Puerto Rican New Yorkers, and The World in My Mailbox.

“Nancy” was an intersection of techniques developed in radio and on LP. Originally produced for Schwartz’s show Around New York on New York Public Radio, he reworked and released it more than once on record. First appearing as “History of a Voice” in 1962 on You’re Stepping on My Shadow: “Sound Stories” of NYC, he re-presented it as “Nancy” on Records the Sounds of Children in 1970. Although utilizing the same base recordings, they told their story a bit differently: “History” utilizes voice-over narration like a radio news piece while “Nancy” edits together sounds in a way similar to Ruttmann. Both were packaged with a cover and notes.

During the period that Schwartz released “History” and “Nancy,” other LP projects approached history more directly. In the early 1960s, for example, Time-Life released The Sounds of History, a twelve-volume set of records that intertwined short explanations of events, readings of documents and literature, recordings, and contemporary music to evoke sonic portraits of important eras in the history of the United States. Later in the decade, torch singer and Batman star Eartha Kitt helped record narrative biographies of important African Americans in the two-volume set Black Pioneers in American History.

The largest engagement with telling history on records during the period occurred, not surprisingly, in the sphere of music. Some did it within music itself—ambitious albums like Duke Ellington’s Black, Brown, and Beige or the Kinks’ Arthur (Or the Rise and Fall of the British Empire) attempt to paint large historical shifts through suite-like musical assemblages. Others used records to present the history of music through documents; record companies, for example, offered overviews of musical genres by collecting together and chronologically ordering recordings. These projects could become quite ambitious—the most cursory and expansive collection of this sort, the 1962 record collection 2,000 Years of Music, tried to capture “a concise history of the development of music from the earliest times through the 18th century” on four LP sides.

“Nancy” and the New Work of History

This is a just sketch, but it gives us a sense of the wide range of work that has been done exploring the narrative and communication possibilities of sound technology before the digital age. They demonstrate the ample resources and precedents to which historians might turn and build on if we wished to expand beyond paper and the PDF. Despite this extensive engagement with sound as a narrative medium, however, these experiments and treatises have largely taken place outside the historical discipline. Sound creators and thinkers have remained outliers and outsiders.

This non-engagement with sound seems surprising, given the significant place that speech plays in the profession. Historians have taught through lectures for centuries, and conference presentations have become an expected part of membership in the profession. These forms of audio scholarship have not been engaged as ‘works’ of history, however, unless published in journals or in edited volumes. It is quite possible that universities’ insistence on written scholarship as the litmus test for academic success has played a crucial role in the centrality of the text within history.

But what might sonic forms of historical scholarship look and sound like? How can historians marshal these forms to tell history? This question remains largely unanswered at the moment, and this openness is full of exciting possibilities.

Listening to “Nancy” once again in another context may give us some hints, however. Let’s listen to the final segment of it, along with something a little more:

Radiolab, “Time”, (2007)

In 2007, “Nancy” was used in its entirety in the Radiolab episode “Time.” Radiolab and other public radio programs like This American Life have built on the foundations of sonic thinking and experimentation outlined above and embodied by Schwartz and “Nancy.” These programs remain most Americans’ contact (if they have any at all) with the legacy and form of these sonic experiments. Although it is not strictly concerned with history, Radiolab consistently employs sophisticated ideas, arguments, and narratives from current historical scholarship. The discussion of time employed as part of their discussion of “Nancy,” for example, is indebted to cultural histories of the standardization of time like Wolfgang Schivelbusch’s The Railway Journey.

Radio and sound recordings are not the only vehicles that we historians have excluded. The other media that seem most obvious for us to embrace—television and film—have also been pushed beyond the disciplinary pale. Ken Burns’s documentaries and the History Channel, for example, are seldom considered part of the scholarly conversation and are often seen as non-specialist intrusions into “serious history,” despite their formative impact on the popular imagination of the past. Incursions by historians into other types of media—like the film version of Natalie Zemon Davis’s The Return of Martin Guerre or Niall Ferguson’s multi-episode version of The Ascent of Money—have been relatively rare and are often conducted or spearheaded by people not considered part of the scholarly community.

The main point is not that all historians need to begin making sound documentaries, but that there are rich resources outside the text that we have neglected. Sound recording is but one device. Indeed, my own experience within the classroom has demonstrated that historians are increasingly moving towards multi-media presentations within teaching—using music on Youtube, photographs, blogs, and film footage—both to expand the range of sources and to try to engage students through the media that are the most familiar to them. Scholarship should follow suit. The increasing move towards the digitalization of academic work—as PDFs or online books—is an incredible opportunity to begin to rethink the historical work. At the same time, it could allow us to dialogue with audiences that are receptive to Errol Morris’s documentaries and podcasts of Fresh Air but who find academic monographs tedious or difficult to approach.

If we accept Walter Benjamin’s argument that perception and communication are historical and formed by their social and technological contexts, then historians are lagging behind. Creating scholarship has long required that historians learn the art of writing; there is no reason that the historian’s craft could not begin to include a fluency in other technologies and media. If, as historians, we took such a turn, we could open up new horizons for historical scholarship and begin to speak a language more attuned to a larger public.

Editor’s Note: For a related exploration of ‘sonic forms of historical scholarship’ see Amber Abbas’s “For the Sound of Her Voice” elsewhere in this issue.