Happy Birds: Darwin on Avian Song

In the beginning was the Squawk, and the Squawk was with Song, and the Squawk was Song.

We humans were not the first to communicate. In fact, as we explore in this issue of The Appendix, we may have learned how to communicate using sound from our distant relatives and predecessors, the animal species that populated Earth for hundreds of millions of years before us. Specifically, birds, whose evolution likely began from dinosaurs in the Jurassic.

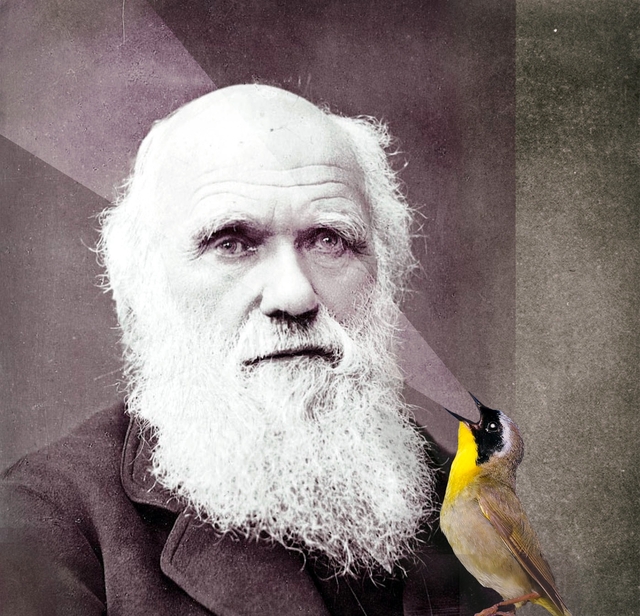

For the Open Source of our ‘Out Loud’ issue, we’ve selected a passage from a thinker whose work brings out the bird-to-human evolutionary connection: the Englishman Charles Darwin (1809-1882). Though hardly obscure, Darwin’s work is not often read in the original. This is a shame, as Darwin was not just the naturalist whom we most associate with natural selection and evolution, but also a fascinatingly controversial observer of humanity.

The following passage is taken from The Descent of Man, and Selection in Relation to Sex, published in 1871, which argued that humans are animals, and that sexual selection explains the seemingly impractical features of humans and animals alike. Although subsequent scholars have questioned some of Darwin’s conclusions (arguing that sex was also important as a social function, and that garish colors and behaviors also served as warning mechanisms) perhaps the most radical implications of the work lay in the realm of race. Darwin was a staunch proponent of the idea that human races were of the same species, not of different species as many race scientists of the nineteenth century claimed, and that exterior differences were superficial.

Yet as the following passage shows, even while writing about birds, Darwin was a man of his time. He held firm views on the differences between civilization and savagery in their customs, and between the roles of males and females. Whether or not Darwin channeled racist prejudice or happily anticipated the extinction of “savage races,” he indeed asked questions that would soon be put to darker interpretations, such as Social Darwinism, and what came to be called eugenics.

This passage, however, sings with bright insight, some teasing ambiguity, and some very funny glimpses of the behavior of nineteenth-century natural historians. (It seems that English scientists swung birdcages about their heads with some regularity.) Though ostensibly about birds and their vocal and instrumental music, it is as much about human interaction, and the emotion, fear, and sexual attraction that humans and birds share. Be it romanticism or insight, Darwin himself leaves the door open for argument. The facts are one thing, but when it comes to interpretation—of theory, of song—we might chalk up our different opinions on Darwin to that underestimated but delightful factor of natural history: taste.

One person’s savage notes are another’s symphony.

Vocal and Instrumental Music

With birds the voice serves to express various emotions, such as distress, fear, anger, triumph, or mere happiness. It is apparently sometimes used to excite terror, as in the case of the hissing noise made by some nestling-birds. Audubon relates that a night-heron (Ardea nycticorax, Linn.), which he kept tame, used to hide itself when a cat approached, and then “suddenly start up uttering one of the most frightful cries, apparently enjoying the cat’s alarm and flight.” The common domestic cock clucks to the hen, and the hen to her chickens, when a dainty morsel is found. The hen, when she has laid an egg, “repeats the same note very often, and concludes with the sixth above, which she holds for a longer time”; and thus she expresses her joy. Some social birds apparently call to each other for aid; and as they flit from tree to tree, the flock is kept together by chirp answering chirp. During the nocturnal migrations of geese and other water-fowl, sonorous clangs from the van may be heard in the darkness overhead, answered by clangs in the rear. Certain cries serve as danger signals, which, as the sportsman knows to his cost, are understood by the same species and by others. The domestic cock crows, and the humming-bird chirps, in triumph over a defeated rival. The true song, however, of most birds and various strange cries are chiefly uttered during the breeding-season, and serve as a charm, or merely as a call-note, to the other sex.

Naturalists are much divided with respect to the object of the singing of birds. Few more careful observers ever lived than Montagu, and he maintained that the “males of songbirds and of many others do not in general search for the female, but, on the contrary, their business in the spring is to perch on some conspicuous spot, breathing out their full and armorous notes, which, by instinct, the female knows, and repairs to the spot to choose her mate.” Mr. Jenner Weir informs me that this is certainly the case with the nightingale. Bechstein, who kept birds during his whole life, asserts, “that the female canary always chooses the best singer, and that in a state of nature the female finch selects that male out of a hundred whose notes please her most.” There can be no doubt that birds closely attend to each other’s song. Mr. Weir has told me of the case of a bullfinch which had been taught to pipe a German waltz, and who was so good a performer that he cost ten guineas; when this bird was first introduced into a room where other birds were kept and he began to sing, all the others, consisting of about twenty linnets and canaries, ranged themselves on the nearest side of their cages, and listened with the greatest interest to the new performer. Many naturalists believe that the singing of birds is almost exclusively “the effect of rivalry and emulation,” and not for the sake of charming their mates. This was the opinion of Daines Barrington and White of Selborne, who both especially attended to this subject. Barrington, however, admits that “superiority in song gives to birds an amazing ascendancy over others, as is well known to bird-catchers.”

It is certain that there is an intense degree of rivalry between the males in their singing. Bird-fanciers match their birds to see which will sing longest; and I was told by Mr. Yarrell that a first-rate bird will sometimes sing till he drops down almost dead, or according to Bechstein, quite dead from rupturing a vessel in the lungs. Whatever the cause may be, male birds, as I hear from Mr. Weir, often die suddenly during the season of song. That the habit of singing is sometimes quite independent of love is clear, for a sterile, hybrid canary-bird has been described as singing whilst viewing itself in a mirror, and then dashing at its own image; it likewise attacked with fury a female canary, when put into the same cage. The jealousy excited by the act of singing is constantly taken advantage of by bird-catchers; a male in good song, is hidden and protected, whilst a stuffed bird, surrounded by limed twigs, is exposed to view. In this manner, as Mr. Weir informs me, a man has in the course of a single day caught fifty, and in one instance, seventy, male chaffinches. The power and inclination to sing differ so greatly with birds that although the price of an ordinary male chaffinch is only sixpence, Mr. Weir saw one bird for which the bird-catcher asked three pounds; the test of a really good singer being that it will continue to sing whilst the cage is swung round the owner’s head.

That male birds should sing from emulation as well as for charming the female, is not at all incompatible; and it might have been expected that these two habits would have concurred, like those of display and pugnacity. Some authors, however, argue that the song of the male cannot serve to charm the female, because the females of some few species, such as of the canary, robin, lark, and bullfinch, especially when in a state of widowhood, as Bechstein remarks, pour forth fairly melodious strains. In some of these cases the habit of singing may be in part attributed to the females having been highly fed and confined, for this disturbs all the functions connected with the reproduction of the species. Many instances have already been given of the partial transference of secondary masculine characters to the female, so that it is not at all surprising that the females of some species should possess the power of song. It has also been argued, that the song of the male cannot serve as a charm, because the males of certain species, for instance of the robin, sing during the autumn. But nothing is more common than for animals to take pleasure in practising whatever instinct they follow at other times for some real good. How often do we see birds which fly easily, gliding and sailing through the air obviously for pleasure? The cat plays with the captured mouse, and the cormorant with the captured fish. The weaver-bird (Ploceus), when confined in a cage, amuses itself by neatly weaving blades of grass between the wires of its cage. Birds which habitually fight during the breeding-season are generally ready to fight at all times; and the males of the capercailzie sometimes hold their Balzen or leks at the usual place of assemblage during the autumn. Hence it is not at all surprising that male birds should continue singing for their own amusement after the season for courtship is over.

As shown in a previous chapter, singing is to a certain extent an art, and is much improved by practice. Birds can be taught various tunes, and even the unmelodious sparrow has learnt to sing like a linnet. They acquire the song of their foster parents, and sometimes that of their neighbours. All the common songsters belong to the Order of Insessores, and their vocal organs are much more complex than those of most other birds; yet it is a singular fact that some of the Insessores, such as ravens, crows, and magpies, possess the proper apparatus, though they never sing, and do not naturally modulate their voices to any great extent. Hunter asserts that with the true songsters the muscles of the larynx are stronger in the males than in the females; but with this slight exception there is no difference in the vocal organs of the two sexes, although the males of most species sing so much better and more continuously than the females.

It is remarkable that only small birds properly sing. The Australian genus Menura, however, must be excepted; for the Menura alberti, which is about the size of a half-grown turkey, not only mocks other birds, but “its own whistle is exceedingly beautiful and varied.” The males congregate and form “corroborying places,” where they sing, raising and spreading their tails like peacocks, and drooping their wings. It is also remarkable that birds which sing well are rarely decorated with brilliant colours or other ornaments. Of our British birds, excepting the bullfinch and goldfinch, the best songsters are plain-coloured. The kingfisher, bee-eater, roller, hoopoe, wood-peckers, &c., utter harsh cries; and the brilliant birds of the tropics are hardly ever songsters. Hence bright colours and the power of song seem to replace each other. We can perceive that if the plumage did not vary in brightness, or if bright colours were dangerous to the species, other means would be employed to charm the females; and melody of voice offers one such means.

It is often difficult to conjecture whether the many strange cries and notes uttered by male birds during the breeding-season serve as a charm or merely as a call to the female. The soft cooing of the turtle-dove and of many pigeons, it may be presumed, pleases the female. When the female of the wild turkey utters her call in the morning, the male answers by a note which differs from the gobling noise made, when with erected feathers, rustling wings and distended wattles, he puffs and struts before her. The spel of the black-cock certainly serves as a call to the female, for it has been known to bring four or five females from a distance to a male under confinement; but as the black-cock continues his spel for hours during successive days, and in the case of the capercailzie “with an agony of passion,” we are led to suppose that the females which are present are thus charmed. The voice of the common rook is known to alter during the breeding-season, and is therefore in some way sexual. But what shall we say about the harsh screams of, for instance, some kinds of macaws; have these birds as bad taste for musical sounds as they apparently have for colour, judging by the inharmonious contrast of their bright yellow and blue plumage? It is indeed possible that without any advantage being thus gained, the loud voices of many male birds may be the result of the inherited effects of the continued use of their vocal organs when excited by the strong passions of love, jealousy and rage; but to this point we shall recur when we treat of quadrupeds.

We have as yet spoken only of the voice, but the males of various birds practise, during their courtship, what may be called instrumental music. Peacocks and birds of paradise rattle their quills together. Turkey-cocks scrape their wings against the ground, and some kinds of grouse thus produce a buzzing sound. Another North American grouse, the Tetrao umbellus, when with his tail erect, his ruffs displayed, “he shows off his finery to the females, who lie hid in the neighbourhood,” drums by rapidly striking his wings together above his back, according to Mr. R. Haymond, and not, as Audubon thought, by striking them against his sides. The sound thus produced is compared by some to distant thunder, and by others to the quick roll of a drum. The female never drums, “but flies directly to the place where the male is thus engaged.” The male of the Kalij-pheasant, in the Himalayas, often makes a singular drumming noise with his wings, not unlike the sound produced by shaking a stiff piece of cloth.” On the west coast of Africa the little black-weavers (Ploceus?) congregate in a small party on the bushes round a small open space, and sing and glide through the air with quivering wings, “which make a rapid whirring sound like a child’s rattle.” One bird after another thus performs for hours together, but only during the courting-season. At this season, and at no other time, the males of certain night-jars (Caprimulgus) make a strange booming noise with their wings. The various species of woodpeckers strike a sonorous branch with their beaks, with so rapid a vibratory movement that “the head appears to be in two places at once.” The sound thus produced is audible at a considerable distance but cannot be described; and I feel sure that its source would never be conjectured by any one hearing it for the first time. As this jarring sound is made chiefly during the breeding-season, it has been considered as a love-song; but it is perhaps more strictly a love-call. The female, when driven from her nest, has been observed thus to call her mate, who answered in the same manner and soon appeared. Lastly, the male hoopoe (Upupa epops) combines vocal and instrumental music; for during the breeding-season this bird, as Mr. Swinhoe observed, first draws in air, and then taps the end of its beak perpendicularly down against a stone or the trunk of a tree, “when the breath being forced down the tubular bill produces the correct sound.” If the beak is not thus struck against some object, the sound is quite different. Air is at the same time swallowed, and the oesophagus thus becomes much swollen; and this probably acts as a resonator, not only with the hoopoe, but with pigeons and other birds.

“The male hoopoe… first draws in air, and then taps the end of its beak perpendicularly down against a stone or the trunk of a tree.” Wikimedia Commons

In the foregoing cases sounds are made by the aid of structures already present and otherwise necessary; but in the following cases certain feathers have been specially modified for the express purpose of producing sounds. The drumming, bleating, neighing, or thundering noise (as expressed by different observers) made by the common snipe (Scolopax gallinago) must have surprised every one who has ever heard it. This bird, during the pairing-season, flies to “perhaps a thousand feet in height,” and after zig-zagging about for a time descends to the earth in a curved line, with outspread tail and quivering pinions, and surprising velocity. The sound is emitted only during this rapid descent. No one was able to explain the cause until M. Meves observed that on each side of the tail the outer feathers are peculiarly formed, having a stiff sabre-shaped shaft with the oblique barbs of unusual length, the outer webs being strongly bound together. He found that by blowing on these feathers, or by fastening them to a long thin stick and waving them rapidly through the air, he could reproduce the drumming noise made by the living bird. Both sexes are furnished with these feathers, but they are generally larger in the male than in the female, and emit a deeper note. In some species, as in S. frenata, four feathers, and in S. javensis, no less than eight on each side of the tail are greatly modified. Different tones are emitted by the feathers of the different species when waved through the air; and the Scolopax wilsonii of the United States makes a switching noise whilst descending rapidly to the earth.

Lastly, in several species of a sub-genus of Pipra or manakin, the males, as described by Mr. Sclater, have their secondary wing-feathers modified in a still more remarkable manner. In the brilliantly-coloured P. deliciosa the first three secondaries are thick-stemmed and curved towards the body; in the fourth and fifth the change is greater; and in the sixth and seventh the shaft “is thickened to an extraordinary degree, forming a solid horny lump.” The barbs also are greatly changed in shape, in comparison with the corresponding feathers in the female. Even the bones of the wing, which support these singular feathers in the male, are said by Mr. Fraser to be much thickened. These little birds make an extraordinary noise, the first “sharp note being not unlike the crack of a whip.”

The diversity of the sounds, both vocal and instrumental, made by the males of many birds during the breeding-season, and the diversity of the means for producing such sounds, are highly remarkable. We thus gain a high idea of their importance for sexual purposes, and are reminded of the conclusion arrived at as to insects. It is not difficult to imagine the steps by which the notes of a bird, primarily used as a mere call or for some other purpose, might have been improved into a melodious love song. In the case of the modified feathers, by which the drumming, whistling, or roaring noises are produced, we know that some birds during their courtship flutter, shake, or rattle their unmodified feathers together; and if the females were led to select the best performers, the males which possessed the strongest or thickest, or most attenuated feathers, situated on any part of the body, would be the most successful; and thus by slow degrees the feathers might be modified to almost any extent. The females, of course, would not notice each slight successive alteration in shape, but only the sounds thus produced. It is a curious fact that in the same class of animals, sounds so different as the drumming of the snipe’s tail, the tapping of the woodpecker’s beak, the harsh trumpet-like cry of certain water-fowl, the cooing of the turtle-dove, and the song of the nightingale, should all be pleasing to the females of the several species. But we must not judge of the tastes of distinct species by a uniform standard; nor must we judge by the standard of man’s taste. Even with man, we should remember what discordant noises, the beating of tom-toms and the shrill notes of reeds, please the ears of savages. Sir S. Baker remarks, that “as the stomach of the Arab prefers the raw meat and reeking liver taken hot from the animal, so does his ear prefer his equally coarse and discordant music to all other.”