Open Sound, Musical Curation, and the Delightful Objectness of Wax: Interviews with Light in the Attic and Clifford Allen

The production of history and the historical archive are traditionally considered the domain of historians. There are, however, a wide variety of archival practices and practices of history that exist outside the academy. Recently, Appendix contributing editor Michael Schmidt sat down over Skype with Matt Sullivan, Kevin Howes, and Clifford Allen and discussed the interstices between music, collecting, archives, and history.

Matt, Kevin, and Clifford unite two different modes of historical work: that of the scholar and that of the enthusiast. All three are avid record collectors and documenters of rare or underexposed music. Matt and Kevin reissue albums through the label Light in the Attic (Matt as the founder and main curator and Kevin as a curator and writer). Trained as an art historian and archivist, Clifford is also a journalist of jazz and improvised music.

Although Michael spoke to Clifford and the Light in the Attic folks separately, their responses touched on a number of similar topics. They spoke about records as cultural phenomena and reissues as a purposeful medium. They discussed the relationship between liner notes, packaging, and music history. Assembled here, their conversations offer a number of poignant reflections on the roles and motivations of those actively shaping the music we listen to, and the way we listen to and think about it.

Origins and Starting Points

Although engaged in complementary endeavors, all three got into their work in different ways. Kevin started as a DJ, Matt worked in radio, and Clifford began writing in graduate school.

KevinBasically, I was born in 1974, and my parents both had reasonably sized record collections. So, I grew up with that. Some of my earliest memories are looking at my parents’ records and listening to them. Looking at the record covers. Talking about records like the early Beatles albums and Sly and the Family Stone. I started to fall in love with the music.

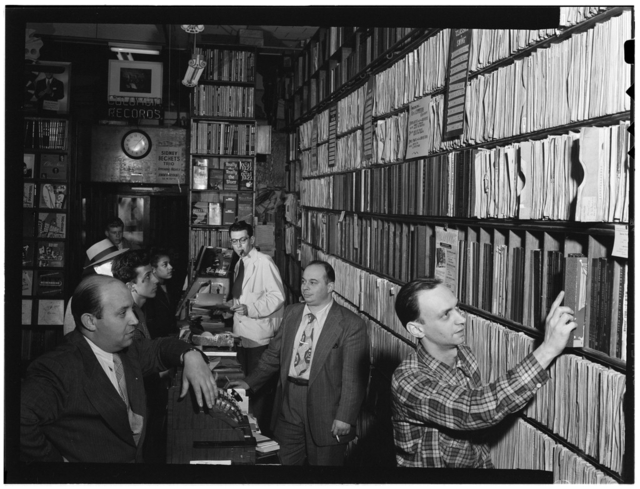

I didn’t really start record collecting myself or buying records until maybe the early 1990s. A lot of the music that I love—rap, reggae, disco, rock and roll—vinyl is (or was) the medium for that kind of music at the time it was being released. Music from the 60s and 80s: it came out on records. I guess by then CDs and cassettes had come into fashion, but records were still relatively affordable, and they were what the DJs used.

So, I sort of got into it like that: starting to find out about sample-based culture. A lot of the music I was listening to in the rap world was based on these old soul and funk and rock records, so it was a natural step to get into that. I started DJing myself, and, once you start DJing, the record is your tool. You want to have stuff that no one else has, and you want to keep up with the latest releases. You start buying records and getting into the habit; you know, collecting them. It’s one thing to have them on the shelf and they look pretty, but I’m all about using the record, wanting to play them and share them with people.

MattI grew up in the suburbs outside of Seattle in a town called Bellevue where we had a small high school radio station. It was 10 Watts (this is 1993-1994). So early on I got involved with that with Josh, my eventual business partner, and we both were in this class where at night you got your own radio show where you could play whatever you wanted. It was a pretty mind-boggling experience as a kid. I liked music before, but that’s where it really hit me. I learned early on that I wasn’t the best musician [laughs] and I liked the idea of curating with a record label and being a part of music on that level.

I’d do lots of internships in college and ended up doing an internship at a label in Spain called Munster Records in 1996 or 1997. Their focus was reissue; they’d been around since about 1984. They were in Madrid and in Bilbao. They were the ones who introduced me to a lot of this older music. At the time most of the music I listened to was contemporary or it would be things that were easily accessible.

At that point I really liked the idea of trying to combine doing some contemporary releases as well as some reissues. The fact that there are zillions of amazing albums by musicians and artists who sacrificed and made these brilliant recordings and then, for whatever reason, their careers didn’t really take off. It seemed like there were amazing albums sitting there that really people should know about.

So I started the label in 2001. 2001 was when it started; 2002 the first record came out. Quickly, we met people like Kevin who has an incredible mind for music, and Kevin turned us on to lots of recordings and we got to work together on that. So that’s where the reissue side of our label started.

CliffordI did some writing in college for a friend’s punk zine, doing very verbose reviews of indie rock and punk records, but that was not really particularly serious in any way. I guess I started [writing about music] as an undergraduate, in an academic setting, writing papers and so forth—those often seemed to spin into music. As far as professionally, it happened while I was in art school in Chicago at the School of the Art Institute. I was working on my Master’s thesis and interviewed Peter Brötzmann for that. I knew John Corbett and he set it up. So, the interview with Brötzmann went well and I had a friend who was starting the New York City Jazz Record [then called All About Jazz New York]—this was 2002, I believe—and he wanted to use the interview.

So that was the accidental start. The [MA] thesis itself was about music: it was [discussing] European free improvisation and process art. But I had not thought journalistically in any sense, so once the Brötzmann interview was published, I became staff on this paper, the New York City Jazz Record, and things just began pouring in afterwards. People began to ask me to do things, whether I would want to contribute and folks would send CDs, and it all took off from there. It was kind of an inauspicious beginning, but it did start earlier than I often thought it did. There wasn’t any “ah-ha, I’m going to do this” moment. It was just one of those things that slowly developed and took hold without any game plan at all.

Peter Brötzmann was the first interview I ever did. Sunny Murray was the second. It was some pretty out dudes right away. Sunny Murray and Buell Neidlinger (the bassist in some of the early Cecil Taylor ensembles). Who else around that time? Burton Greene—he might have been a little later. Charlie Haden was really early for me and that was pretty cool. I got to talk with all of these very heavy folks at the beginning and sort of front-loaded the process, which I think was good: trial by fire.

Knowing how to navigate [conversations with] these complex human beings with a lot of history early on was helpful. It sets up how you think about the rights and the wrongs [of the process] pretty early on and I think that it was good to jump into the deep end of the swimming pool very early.

LITA on Listening

Listening is an activity that is both historical and individual. For those working in and/or devoted to music, the ears are an important thing to cultivate. The way one listens is quite informative—it says something interesting about the fundamental way that one approaches music. Matt and Kevin discussed different ways that they listen to recordings and the way that their practices go beyond just the sounds on a CD, cassette, or audio file.

MattFor me, now that I have a wife and a child and a house that’s maybe not so big, it’s hard to listen to music at home sometimes. I do listen to music at home, but I’m not able to just sit down and zone out. So, a lot of times the car is actually a really nice place to listen to music and get the vibe of it. Living in Los Angeles, you’re in a car a lot. I also listen to music at work all the time. It’s not like everything we listen to at work has to do with what we’re working on; I think it’s kind of hard to listen to work and focus on it. It’s not that it’s always background music, we’re enjoying it and talking about it, but when I was younger it would be a lot more of getting stoned and putting headphones on and listening to records or cassettes or CDs over and over again. Now it’s the car. Sometimes late at night at home when everyone else is asleep, I’ll be listening to music on my own. The car and late at night is the best time. I like really getting into a record when it isn’t just background music. A lot of times I’ll buy records and won’t listen to them for a long time‚ like six months or maybe a year‚ because I really want to listen to them at the right moment. I hate listening to music when I’m forced to listen to it. I like being able to look at the covers, read the notes, and just lay back and listen to it.

Also hiking is a really nice way to experience music I’ve found lately, just on my headphones. So, yeah, being mobile, I prefer that. On a hike, in particular, you pick out scenery that you’re enjoying, and you can find music that fits the mood really well. While in the car you might be stuck on the highway; depending on what you’re listening to it might be calming or it might make you angry. So a more natural setting can always be a nice environment.

Kevin on Environmental Sounds

KevinIn those contexts I really prefer the open sort of sound. I don’t like using headphones too much, especially walking around. I like to catch the environmental sounds as well.

I like hearing the sounds of the road as well. I don’t want to totally internalize with the process. I like combining it with other things. It’s almost like a mix in a way. Like if I’m outside and I’m hiking or whatever, I’d rather walk with a little cassette player that played it out and I could hear the nature sounds. Not that I do this, but in my mind that’s how I’d like it to be.

Or if I’m sitting at the beach or something, and have a little player that you can just listen to instead of putting the headphones on and just internalizing. I like to hear the surf with it as well.

It’s like if you’re mixing two records on a couple turntables and a mixer, blending records together. The environmental sounds, the nature sounds, are almost like another channel, you know? It’s another texture the music can interact with. It sounds super hippy-dippy, but I really like even just nature sound records. You have vinyl records, and you know CDs, of relaxation music. The Sounds of the Ocean‚ A Walk by a Gentle Stream—I’ll buy these records. I collect that type of stuff. I love it. It’s just another way of listening; an added texture. Sometimes you can get a really neat sync thing or synergy with it where it becomes its own entity.

Interviews and Oral History

One of Clifford’s main occupations as a music journalist is interviews. For scholars of music, interviews are often one of the few sources that we have of musicians speaking about their music in their own voice (other than the music itself) and they often provide essential information about sound events which are not very well documented. We spoke about how he approaches the interview process and how he thinks it relates to oral history.

CliffordI definitely think of [my] interviews in part as oral history, though with a different sort of underpinning. For example, if you go to the Online Archive of California [OAC] and you look at their oral histories, they start from the very beginning, “where were your parents born?,” with very specific trajectories. There is a great oral history with Anthony Ortega, the alto saxophonist, who, I believe, still lives in LA. [He is a] really wonderful saxophonist, recorded for Revelation and for, I believe, the old Dawn label. He’s a Mexican-American Charlie Parker acolyte, so he has an interesting story. The transcription is all available at the OAC; he’s not right away talking about playing in Los Angeles jazz clubs in the 1950s; he’s talking about what his parents did and that sort of thing.

That sort of oral history is very specific. What I do—I don’t put that into the same category. When I interview musicians, their story comes out in conversation as much as they like to tell [it] but a lot of it is centered in their music and thoughts. Biography is necessary, although I don’t think I treat it as though it were a familial oral history or an oral history of—say, the context in which Sunny Murray grew up in Oklahoma. I mean that stuff comes out, but tracing his life from those early pre-musical stages to his living in Paris, that’s a totally different enterprise than what I was trying to glean, which was more to understand his process and work.

I’m interested in how musicians’ work transpires, how it comes to be, their process as creative artists, how they compose, how they view composition—either as improvising composers or if they are actually writing tunes. I’m very interested how they put together the bands and ensembles, how they view their work in terms of placing it in some sort of sonic continuum. I’m also interested in musicians who may have connections to other art forms or, say, improvisers who may play other types of music or musicians who may be visual artists or are writers or are connected to other creative endeavors. I’m always interested in that kind of stuff: to see how the whole person thinks. For me, I really like having a dialogue with people about creativity and each interview is very different. So, that said, some salient historical points might get left out because I’m interested in getting at their essence as creative beings, and trying to put that out there for people to read and enjoy. It may be a bit more nebulous than providing a straight historical lineage.

Records, Record Collecting, and Personal Archives

Collecting is driven by a fascination with specific objects, and collections can become personal archives. Acquiring and bringing together a large number of similar objects opens up interesting questions: how do these objects relate to each other? How do I organize them? How do I find meaning in these objects and how do I distinguish them? We tend to think of music only as sound, but commercial records are multi-faceted objects that communicate through various means. Clifford is also trained in Information Science as an archivist and we discussed how he views records and how he has confronted the organization of his collection.

Clifford on Records

CliffordWhen I approach an old record, say in its original or as close to original form as can be found, I think of those as art objects, although they might be mass produced sometimes. I think of them in their context. It’s less thinking of them as historical stand-ins for a specific time period and more thinking of them in terms of their objectness, in terms of their beauty as physical things, graphically, etc.

With records, there are so many aspects to a record as an art object. It is a record of something that occurred, literally. Musically, it is a record of what happened at a point in time. It is also a graphic design object. And it is a piece of text. So there are a lot of things going on and sometimes they can be difficult to separate from one another and I think that is kind of cool. I also like the mysterious aspect of a lot of records that have no notes and that seem to come from nowhere. What is this thing? And sometimes any effort to uncover what it is will be met with obstinance. And as an art historian, those objects that were not easily yielding were always pretty interesting to me.

MichaelIn what ways do you think about your records as an archivist? I sometimes play around with organization. It’s interesting to view records or connect records physically according to different themes.

CliffordI used to do more of the organizational play. I would divide things historically or contextually. So, like, all the AACM records would all be together. The Black Artist Group would all be together. The [Albert] Ayler, [Archie] Shepp, and Coltrane, the Pharoah [Sanders] and so on, would all be together. The European stuff would all be by country and sub-divided even more, by regional weirdness or whatever. Say with the Dutch guys, an ICP section [Instant Composer’s Pool] and then a not ICP section and so on and so forth. I don’t do that now. It got to be too much a pain in the ass. For like Grachan Moncur III, you know, you’ve got his Blue Notes, and you’ve got his Actuell, and you’ve got his Jazz Composer’s Orchestra and where do you put them? There are many artists like that that spanned the genres. Or Wayne Shorter. It would be hard to file them together. Or file them apart. You’re kind of stuck there. So I just do genre and alpha, chronological by album now.

But as a personal archive, sure, yeah, I do try to, as much as the pocket book allows. I do try to document as much as I can any area I feel interested in or feel needs work. I mean there’s always more stuff to check out. And I’m very attached to original forms of recordings so I try not to have too many reissue LPs. I try to have original pressings and [to have them in] their most representative, most aesthetically pleasing, and earliest form.

I don’t like surface noise. If you view these things as art objects, you wouldn’t want a ruined painting, so why have a ruined [record]? I’m of the mind-set, at least in the case of records, that I’d rather not have it than have a trashed copy.

Reissues and Documentation

At heart, reissues are anachronisms. They take musical artifacts produced by specific actors in a specific context and re-insert them in a different time, often involving different actors. This combination often creates a remarkable and complex blend of intentions and meaning.

Reissues are also, however, a means to document and illuminate the musical past. This occurs most obviously in terms of the sound content of the music itself, but physical albums also offer a host of resources to frame what comes out of the speakers.

MichaelOne thing that strikes me about reissue labels is that it they are about creating a certain image of taste, of being a curator of people’s tastes. It seems like part of having a successful reissue label is about people trusting your taste and wanting to buy something that they’ve never heard before and know nothing about based on their trust that you’re putting out interesting stuff. Is that something that you actively think about?

MattYeah, all the time. That was the goal from the beginning. I looked at labels like Creation Records or Stax—labels [that] you trusted. Maybe in the 80s or early 90s you’d read about a new Sub Pop release or a Stax release back in the day, and you’d go buy that record just because it had that credibility.

For me that was always really important, from the beginning, for Light in the Attic. I wanted for us to try to do our best. I want people to say, “I bought the Jamaica to Toronto release, and that was really cool,” and they go to the record store and see Karen Dalton. They’ve never heard of Karen Dalton, but they see the Light in the Attic logo and they say, “Well, I’m going to give this a shot.”

Karen Dalton, whose 1971 album In My Own Time was reissued by Light in the Attic Records, with Tim Hardin in Boulder, CO in the 1960s. Nicholas Hill

Maybe this has always been the case, but it feels like now a lot of people are focused on doing quantity rather than quality. So, for me, less is more. That’s important. Kevin probably feels the same thing about everything he does. I just don’t want to contribute more crap to the world. And I don’t want to‚ when most of these artists had failures back in the day, I don’t want to be another person contributing to their failed career. Therefore, if we’re going to do something, I want to do it the best we can. Some things are going to do better than others, but at the end of the day, regardless of sales, I feel like I can look at each of the releases and say, “that had some nice liner notes and [we] documented the release and the artist the best we could and had some photos and we got the best audio source material we could and remastered it the best we could.”

KevinI think it comes across in the releases, too: the detail, the multiple formats, the liner notes, and booklets. The accoutrements that pop up here and there. I think it resonates with people, serious music fans who are interested in this kind of music.

Matt on Re-issues

MattMost people are consuming music in a different way. Most people aren’t paying for music, so you really need to give people a reason why they should be buying this. We don’t want to create something that’s disposable. You tend not to throw away a coffee table book. Our hope is that people really enjoy this music and get something out of it, and hopefully don’t just throw it in a corner like other things you do in your life.

CliffordI really think if you are going to do a reissue you really have to do it right. You can’t fuck around. It’s gotta be nice.

MichaelIf I can interject, what do you think doing it right is exactly?

CliffordDoing it better than the original.

MichaelIn terms of sound quality?

CliffordIn terms of presentation. If you are going to encourage people to buy this again, it has to have something that the original doesn’t have. I’ll just use the example of the Bill Dixon Intents and Purposes record. It was done from the master tapes and a nice little gatefold CD package reproducing the original cover. Remastered from the original tapes, sounds great … it was definitely done “right,” but the caveat is, the Dixon estate has reams of photographs, of materials relating to those recording sessions. There is extra music, you know, rehearsal tapes. My view is that is should have been done as a deluxe reissue. If you have access to all this extra contextualizing material for a singular recording, if it’s something that is a cornerstone, you should do it.

MichaelSo ideally you see reissues when they are done right as being as a medium for presenting all available materials?

CliffordYeah, totally. I should qualify that, because I don’t think every record needs it, but if you are going to do a reissue of something that hasn’t been out in CD format before, for example, I think you should feel like you are in the position where you can do something really special that will really illuminate the project. I think that is different than say the deluxe box reissue of Kind of Blue because it’s been out 3,682 times.

MichaelI think it’s interesting: you were talking about when you buy records on vinyl, you want it to be as close to the original, to keep the integrity of the artwork as much as possible. But reissues for you are something different, something more like a medium for documentation.

CliffordYeah, as an homage.

To me that is what a reissue should be. I think it should have it’s own kind of life. If it’s not ‘better’ than the original then at least it should be a paean or a serious homage to the fact that the original exists.

MichaelWith jazz, it seems to me that reissues are way more commercially successful than new recordings. People will have a jazz collection and it will all be from the 50s and 60s and have nothing new. Clearly reissues are vital to sales of the genre but why do you think it tends to be such a historicist type of listening, versus one that is actively seeking out contemporary music?

CliffordYeah, I think there is a fetishization of the old, as clichéd as that sounds. I don’t want to repeat clichés, but here we are. I’m as guilty of it as the next guy.

I don’t know. My feeling is that one has to be pretty careful about these things, especially with artists who are still alive and are still making new recordings. Those [recordings] tend to get overshadowed by the reissues and I think that is really unfortunate. Bill Dixon, for example, he made cornerstone recordings for RCA Victor in the 1960s that were reissued and a nice job was done, but he was at that time still making work.

So the reissue came out at the same time as his final recorded work and there was this fear that—and I think this was fairly accurately borne out—the reissue overshadowed the new recordings, and people are still clamoring about that older work, when he was doing fundamentally powerful work until practically the day he died. His final recording was made just a few weeks before he passed. Burton Greene is another example. His new recordings are wonderful, but people still just talk about the ESP [recordings] and those were done in 1965-1966. I don’t know why people put so much stock in older recordings. I don’t think it’s just jazz. I think in rock music it’s the case too. I don’t that Glenn Branca’s newer symphonies are really given the same level of attention as his early work, probably to the detriment of his pocket book. I don’t have an answer for it. I think it’s a cultural symptom. We tend to like to see the past, we’re interested in it. A historian has insight into our obsession with the past, and reissues are certainly great to have available as important historical documents, but, at the same time, there is a paucity of attention paid to contemporary work.

It’s a tension I’m well aware of—as a record collector, I’m buying old stuff. And some days I feel like—some weeks I feel like—giving way more attention to that type of listening than new jazz record X,Y, or Z that, for all intents and purposes, is equally interesting.

MichaelOne of the things that I think is interesting about reissues is that it’s taking music that was recorded in another time and place and another context and, essentially, most of the time it didn’t stick. Then you put them out in the present, in this foreign context—what do you think makes records that didn’t stick then stick now?

MattSometimes it just takes years for people to catch up to things. It’s clichéd sounding, but it’s true. Some of these records and artists were just before their time. People weren’t ready for it.

KevinYeah, they just didn’t find their audience in the past. You know, a lot of these records being reissued today were regional things and things that generally didn’t have a big push in the media or by a major record label. If they didn’t hit really big at the time, they just fell through the cracks. Life goes on. Some musicians from the 60s and 70s, they started families and moved on to other things. They had to pay the bills, and music wasn’t paying the bills. But, just because something didn’t reach commercial success back in the day doesn’t mean it’s not good music. That’s one thing that we’ve all learned about.

And I don’t think that everything from the past is worthy of reappraisal. The good stuff will rise to the top eventually. It just may take twenty or thirty years.

One thing I can note is that, with the digital age that we live in, a lot of the music of today is documented. A band will have their BandCamp pages, any number of websites documenting and promoting their music. Kids at shows have phones and digital cameras. So much stuff gets documented. But if you look back forty years ago, they didn’t have iPhones in ‘67, obviously. A lot of these great bands didn’t even have a friend with a camera around at the time. So the pioneers of a lot of the music that gets copied today isn’t really documented.

The motivator for my work with Light in the Attic is preserving and documenting history which will be lost if it’s not preserved now for future generations. I think that would be a real shame if the pioneers of a lot of pop rock and other kinds of music—if their history were to just get lost, if someone doesn’t take the time to talk to the musicians. It doesn’t have to go as far as a reissue, but, you know, preserve it. People do that a lot today with blogs, and I think it’s commendable. Light in the Attic goes a step beyond that. They put so much time into these reissues, documenting them for future generations who I hope will have access to them.

I worked as a DJ for years and I worked in the newspaper business as a music journalist for years as well. And over the years, as I’ve been exploring music that hasn’t really been documented very well, that’s actually something I really get a kick out of—finding stuff that’s not Googleable. If I go out and I find a 45 on an independent label, and I come home and look it up online and there’s no information, that’s the kind of stuff that I actively want to find all the time. That really excites me: that not everything can be found through Google, that there’s still a bit of mystery.

How I connected with Light in the Attic was [that] they were looking for information on a Jamaican artist by the name of Wayne McGhie. So you type “Wayne McGhie” and you might find a couple little things, but it doesn’t tell you very much. You look in The History of Canadian Music, the encyclopedia, and you look up his name in the index and he’s nowhere to be found. You look in the Toronto Star and the other newspapers of the day and there’s no information. You love the music so much, you want to know, “How was this record made? It’s incredible! What the heck was going on here?” You have to go direct to the source. You have to go to the musicians themselves, obviously. That’s been a catalyst for a lot of this work. You talk to these players and you hear these stories and you listen to the history behind these records and it adds a lot to them. It provides context. Once you have this knowledge, you want to share it with other people, so that you can document some of this history. It’s really important.

MichaelI have another question about the choice of you guys putting out original artwork. A lot of reissues, like jazz reissues in the seventies and eighties, would completely remake the artwork. Why do you guys choose to put out the original artwork?

MattWe tend to want to want to stay true to the historical piece in our hand, and that means the original album cover.

KevinIt’s nice to have that link, obviously. That’s what inspired us in the first place with both of these records: it’s the artwork, the albums, you stare at them for hours and that’s what inspires. So to be able to recreate that and to put that out and share what inspired us about these things in the first place is phenomenal.

MattWe try often to find the people who made the album cover, but we tend not to be able to find them. We found the [cover artist for] Wayne McGhie, though. We spoke to him, or Kevin did. You know, you always hope to have more photos from the session or good stories, but I don’t think he remembered a damn thing. [Laughs]. I don’t think he even remembered the cover.

KevinMost people involved in the creative didn’t keep stuff. One thing I’ve noticed talking to a lot of the veteran musicians and producers, people in the sixties and seventies didn’t foresee this future interest in the music. It was over. The album didn’t sell. It was done. No one in their right mind would think that thirty years later there’d be these young kids and music lovers passionate about these recordings that didn’t sell at the time. They threw out the master tapes. They threw out the original artwork. A lot of the artists don’t even have copies of their own records anymore. No one could predict this renewed interest.