The Descent of the Lyre

For several years, I traveled in pursuit of a strange image: an icon of a guitarist-saint with bandaged hands. Looking back, I am no longer sure how it was that I first imagined or dreamed of this image; but it must have been some time back in 2005 or 2006, when I made two short visits to Bulgaria, claimed home of the mythical musician-king Orpheus. On those two visits, I spent a lot of time visiting mountain valleys and hillside chapels; and after my return from one or another of these journeys, the image of this saint appeared to me—the guitar, the bandaged hands, the grave expression. As time went on, this image came to obsess me so much that eventually, despite the fact that I am not a painter, I sat down and painted my first and only icon painting, working in gouache on board.

There is and never has been any such saint; but having painted the icon of this strange figure, I felt somehow bound to him. Then back in 2007, I had the opportunity to travel to Bulgaria for a third time. On this third journey, I set out with three things: a guitar, the crude icon painting, and the intention to write a novel about this invented saint, this unorthodox Orthodox saint. His name, I already knew, was Ivan of Gela, or Ivan Gelski, his surname taken from the name of the Bulgarian village that is said to have been the birthplace of Orpheus.

I spent eight weeks traveling through the mountains and small towns of Bulgaria, accompanied by my guitar and my patron saint; and I returned home with a clutch of notes and drafts that eventually became my novel, The Descent of the Lyre (2012).

This novel, in the form that it has eventually taken, is perhaps best seen as a series of variations on the theme of Orpheus—following the life of Ivan Gelski from his childhood in the Rodopi mountains, to his adulthood as an outlaw in the hills of Bulgaria, to his success on the concert stage of Paris as a guitarist, to his eventual return home as a saint of sorts. Here, I reproduce three extracts from the novel: three variations that relate, in one way or another, to the story of Orpheus.

The book is finished and is now in the hands of readers, but that original image of Ivan Gelski still stares down at me from the mantelpiece. As I meet his gaze, I still feel a shudder of obligation towards him as his first and perhaps only disciple. I had not expected to spend so much time recounting his life—his zhitie, or saintly biography, as they say in Bulgaria.

Painting saints, it turns out, is something of a perilous undertaking.

Extract One:

The first extract comes from the very beginning of the book, set in the village of Gela before Ivan’s birth. It tells the tale of how the future guitarist’s uncle meets with his untimely death, and how Ivan, even whilst still in the womb, has already become a musician.

The music was already there before he was born. He lay in his mother’s womb and listened to her heart thud like a tupan. His eyes were closed, but his ears attuned to the rhythms of his mother’s body—the unsteady ruchenitsas of her laughter, the slowing and quickening kopanitsas of her changing moods, the steady pravo horo of the hours she spent weaving at the loom. The music was there, as if awaiting his arrival, lying in ambush for him as he made his way down the road that led into existence.

He was the first of his mother’s children to live beyond the womb, the first to open his eyes and see the soft green of the upland fields and meadows of the village of Gela. An elder brother and sister, twins, had died the year before his birth. His mother would later consider him to be not the first, but the third.

The music was already there, not only before his birth, but before his conception. His uncle, his mother’s brother, had been a musician. His name, also, was Ivan. And he plucked the strings of the tambura with such sweetness it was said to bring peace to the animals of the forest, to calm the hearts of bears and wolves, so that they would lumber away and cause nobody any harm. Like Orfei, the old women of the village said: like Orfei, who once had been king. But uncle Ivan had killed himself in the spring before the child’s birth, whilst his nephew swam, no larger than the length of a human thumb, in the many rhythms of his mother’s womb.

They found the body hanging from a cherry tree, drenched in a rain of yellow blossom. When the fruits budded and swelled later that year, they were more abundant than anybody could remember.

Nobody asked why uncle Ivan took his life. In times such as these—when the countryside was full of robber bands who would cut a man’s throat for a few coins, when Sultan Selim III sat uneasily on his throne listening to a million insects gnawing at the foundations of the empire, when those who toiled for a living on the hillsides were at the mercy of the rich, as they always are and always have been—in times such as these, what requires explanation is not why a man should wish to die, but rather why life persists at all.

A child, no more than seven or eight, brought the news of the suicide. Wandering on the hillside he had seen the man’s body hanging from the tree. He ran to the village in tears. The dead man’s sister, on hearing the news, touched her hand to her belly, retired to the house and closed the door. Through her tears she murmured blessings upon the child; and the child, shut in the singing, pulsing cauldron of her womb, listened as she sang her brother’s name, over and over, two syllables, the second stressed, like the uneven steps of a dance: Ivàn, Ivàn, Ivàn.

Extract Two:

Ivan is now living in the hills, having taken to banditry after the abduction of his bride-to-be on the night before their planned wedding. Several years have passed, and he is now leader of an outlaw band. It is here, in the mountains, that he meets with the Jewish-Croatian guitarist Solomon Kuretic, who is captured while traveling to the court of the Ottoman Sultan. After his capture, Ivan offers a challenge: either the guitarist must play something to ease the suffering of the outlaw’s heart, or he will be killed.

Solomon did not need to wait long. Ivan returned to the encampment within the hour. The first sign of his arrival was the gaidar, who ceased playing his pipes. Then Ivan appeared out of the darkness, on the further side of the hill. As he came close to the fire, Solomon noticed the grave, bearded face, the deep-set eyes that had something wild about them. The new arrival, the Voyvod, spoke with Boyko the standard-bearer, then he came from the fire to the tree where Solomon was tethered, accompanied by the German-speaker. He crouched down in front of the prisoner and looked into his eyes. Solomon looked back, blinking occasionally. For the first time since his capture, he felt afraid. And cold, too, with the wind that came across the hillside. His head throbbed where it had hit the rocks. The moment he thought of the pain, it came flooding back, and he winced. He could smell Ivan’s breath, and the animal reek coming off the furs he was wearing. The one who spoke German muttered something to the Voyvod, who broke his gaze and turned his head. The two men conversed for a while in Bulgarian. Then the Voyvod walked over to Solomon’s guitar case, which was lying to his side. He kicked it with his toe, but gently, and asked the German-speaker something.

“He wants to know what it is,” the German-speaker translated.

“Tell him it is a guitar.”

The Voyvod looked puzzled.

“Music,” said Solomon.

“Muzika,” the translator said.

“Muzika,” Solomon repeated.

Ivan Voyvoda frowned, and then muttered something else to the translator.

“He says that he wants you to open the case. He wants to see the instrument.”

“You will have to untie me first.”

After a short discussion, Ivan leaned over, and taking a knife cut the ropes that tied Solomon. He said something to the translator, who had taken his pistol from his belt and was pointing it at the musician.

“Open.”

Solomon got to his feet, but he was stiff from long sitting, and he wavered a little, steadying himself by reaching out to the trunk of the tree. Then he undid the latches of the case and opened it. The top of the guitar glowed dull orange.

“Tambura,” said Ivan.

“Kitara,” the translator replied.

Ivan stood over the captive, watching him lift the guitar from its case. As the prisoner picked up the instrument, his hand brushed lightly over the strings, which hummed in the night. The image passed through Ivan’s mind, so fleetingly that he hardly noticed it, of a blizzard of yellow blossom.

Solomon stood, holding his guitar in his hand. “Kitara,” he said, and he smiled.

Ivan did not smile back. He spoke to the translator for a few moments more, then turned and headed back towards the fire. The translator, who was still pointing the pistol at the musician, spoke softly. “The Voyvod has offered you a wager,” he said.

“What kind of wager?”

“It is simple. He has gone to prepare a place for you by the fire. Tonight, the Voyvod will give you food and drink, and all the hospitality that is proper for an honored guest. Then he will ask you to play.”

“And the wager?” Solomon said.

“The wager is this. If you play with sufficient skill to ease his suffering, he will spare you. But if your playing does not please him, if it does not still his rage and his pain, he will kill you.”

“If I am to die,” Solomon said slowly, “how shall I die, and when?”

“Our Voyvod will make sure your death is quick. If you have not succeeded by the time that the sun rises over the hill, then he will plant a bullet here.” The translator gently pressed his gun into the middle of Solomon’s forehead. Then he placed it back in his belt and put his arm around the musician. “But that is for later,” he said. “For now, let us eat and drink as brothers.”

So the two men went to join the circle by the flames, the tall, pale Jewish musician who held his guitar in his hands, and the merchant who had fallen on hard times; and when Solomon took his seat, the haiduti welcomed him, as if he was already one of their number.

Ivan sat on the far side of the fire, poking at the embers with a stick.

Solomon shivered as the haiduti passed around clay cups, glazed with green and filled with rakiya. Ivan Voyvoda offered a toast, raising his cup, and the men all responded, taking care to look each other in the eye in turn. Solomon swallowed the brandy and tried not to wince, but in truth he was not feeling much like feasting.

The German speaker, who only now introduced himself as Asen, and who became increasingly voluble and friendly the more they drank, translated for the musician, and the other men pressed him with questions about life in Vienna, about the women there, and about his music. It would have seemed that the band were a model of hospitality were it not for the fact that hanging over Solomon’s head was the threat of death the following dawn. Yet in this respect, he was no different from the others, for whom every day offered the prospect of a new and different death. Solomon was not the only man on that hillside who was living in the shadow of his own destruction, and perhaps it was this, above all, that led to the sense of kinship, even of friendship, that his captors felt towards him.

Whatever the reason, they broke bread together, drank rakiya and wine, feasted on fish pulled from the streams and the rivers—silvered trout that crackled as they cooked on the embers, and on mutton and on blackened peppers that tasted of sun. And although Solomon wanted more than anything to keep his head, so that he might play well—he had played for love before, for the hearts of women, but never for his life—he could not refuse the endless toasting, so that by the time the evening was well advanced, he was singing haidut songs along with the others, accompanied by the gaidar, songs of bold raids, of fallen friends, of hatreds and revenge and of quiet meadows where the trees sang with the sounds of finches and sparrows. And even though he did not know the words, it did not matter. He made up his own words, singing about his home, about the Danube he loved, about Clara, about his childhood, so that had he not been already driven half-mad by his long journey, by the blow to his head, by the fear that was growing inside him moment by moment, by the drone of the pipes and the rough sound of so many men’s voices, he might have stepped back and wondered that this was a strange way to spend what could be his final night on earth.

But he sang also because whilst he sang, the moment when he would have to play had not yet come; because whilst he sang, he could imagine that he was simply a traveller enjoying the hospitality of shepherds and villagers, a traveller who might, when the dawn came, depart on the road that led east to Constantinople.

When the moon was high overhead, the singing came to a close. The gaidar ceased playing, and Ivan Voyvoda said something in a low voice, something that made all the men laugh, all except Solomon. Asen did not translate. Solomon was swaying a little, more drunk than he could remember having ever been; and when he managed to focus, he saw that there all of the men were staring at him.

Solomon took the guitar and placed it in his lap. He wrapped his arms about it and closed his eyes. The world was pitching and reeling like a ship. Ivan Voyvoda muttered something else, and this time Asen did translate. “The Voyvod asks you to play,” he said. “He asks you to play to ease his suffering heart.”

Solomon ran his fingers along the strings. His pale right hand hovered over the sound hole, his left crouched on the fingerboard. He paused, tested the tuning, and made what adjustments he could; but because of the drink it was hard to be sure whether he was making things better or worse. Then he played a chord—an E minor that set the four open strings thrumming—just to test the sound. He ran through another few chords. Then he looked into the fire.

What can a man play, he wondered, to save his life? And because none of those things he had performed on the concert stage were adequate to the occasion, because an encampment in the Rhodope mountains, surrounded by men who have just slaughtered every last one of your travelling companions, is no place for delicate Viennese waltzes, for the fripperies of the salons of Europe, he simply let his fingers guide him. He played the lightest of passages in harmonics, echoed them on the bass strings, playing in heavy rest-strokes with his thumb, a melody that came to him from nowhere, or perhaps from everywhere, from the long road he had travelled, from his regret at leaving Clara, from the fear that was settling in his belly, coiled like a guard dog only half-asleep, from these hillsides with their gorges and valleys, their upland meadows and rushing streams filled with trout and fringed by green ferns, from the music he had heard played in the houses of peasants along the way, from the sky above with its incomprehensible stars, and from the eyes of the men who sat listening to him, immobile, no longer even passing around the rakiya, but simply listening. The melody inched its way up the stave, fugue-like, repeating each time, but never quite the same, a melody like the river that, as some sage once said, one can never step into twice, but that remains the same river. There were waterfalls of arpeggios, swirling whirlpools of triplets, slow-moving depths on the lower strings, clashes that were only partly resolved before becoming still further clashes, dissonances and tensions and cross-rhythms that built upon each other until Solomon’s hands were a blur; but somehow, out of this chaos of notes, the same melody, returning again and again. Then his hands slowed, and his left hand moved up to the top of the fingerboard where the melody appeared once more, modulating into the minor key with such extraordinary sweetness that—had he still been walking in those hills, had he not been torn to pieces by savage women as a punishment for spurning their advances—even Orfei himself would have wept to hear it. Solomon pulled the melody from the guitar in long skeins, drawing it out like silk. And then the tempo quickened, the discords becoming more pronounced, rhythms of the soil and of the rocks and of the trees, uncountable rhythms felt only in the body, beginning to take over. The gaidar smiled and leaned forward. He had heard nothing like this before, and yet it was as if he had always been waiting to hear it. His fingers twitched, following the flood of ornaments and grace notes. Asen leaned back, breathless. Boyko put his face in his hands, for what reason it is impossible to tell. And Solomon played on, as the sparks flew up into the night, and the dead on the hillsides, unseen, clustered around to listen, because it is not every day that you get a concert such as this, and if the dead are not easily roused, they are not entirely intractable; and as the dead assembled, although they could not be seen, the haiduti shivered at their presence and at the strange spell that Solomon was weaving, not a music of the head, nor even of the heart, but of the hands that danced like ghosts in the firelight, the hands and the body and the ancient earth singing through the body and the sinews and the blood.

Then the melody eased, became simple again. Played on the bass strings. Echoed once in the higher register. Again, but more gently, in the bass. And again at the top of the guitar, but in harmonics, clear and pure as a mountain spring, the final note so quiet that it was not certain whether it was played, or simply imagined.

Solomon opened his eyes. His head was pounding and he was damp with sweat. He looked around the fire. Nobody clapped. Nobody moved. Then he saw Ivan Voyvoda: and tears were streaming down the man’s face.

The Voyvod rolled his shoulders and cleared his throat. His men turned and looked at him with astonishment, for they had never once seen him weep. He then let his head hang, so that the tears fell into his lap. His verdict was murmured so softly it was almost inaudible. “The Jew lives.”

Extract Three:

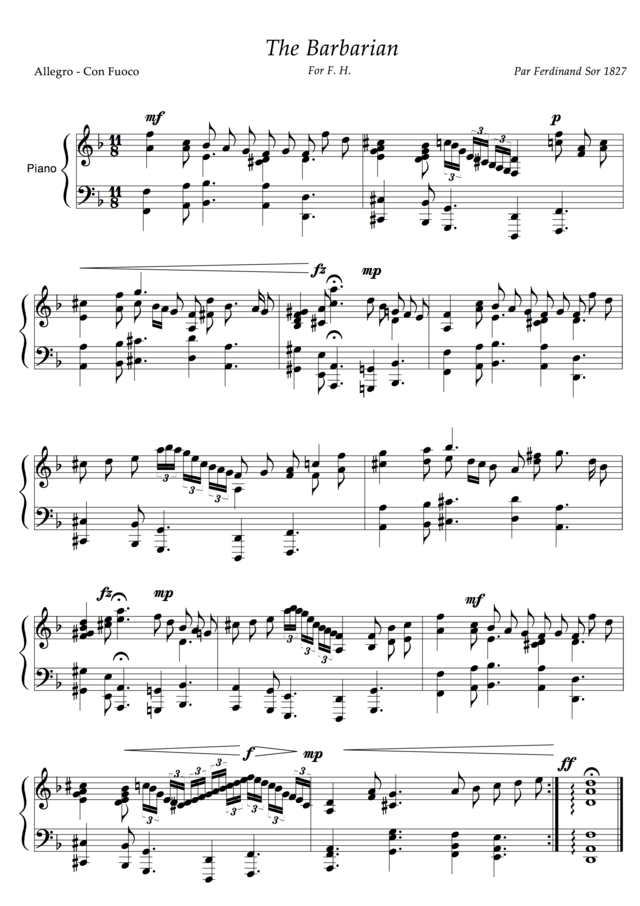

The final passage comes from a later section of the book. Ivan’s encounter with Solomon eventually leads him to take up the guitar and travel to Paris; but the protagonist in this final extract is not Ivan. Instead it is the Spaniard Fernando Sor, one of the greatest guitarists of the early nineteenth century, and the catalyst for Ivan’s eventual transformation from guitarist to saint.

The sickness was getting worse, and the rain did not help. It made him long for the clear cold of Moscow. Or for the warm sun of Spain. But not London, that wretched town with her mist and her foul odours that drifted up from the all but lifeless river, and her squat, charmless citizens. He longed for everywhere except London.

Ferdinand pulled the blankets more closely around himself, and leaned towards the fire. The rain was streaming down the window with steady determination, as if it did not intend to let up for weeks. Through the glass, he could see low clouds, brown and heavy. He shivered again, and muttered a prayer to the Virgin in Spanish, the prayer that as a boy he had intoned every morning in the monastery school of Montserrat, and that was almost the only thing that remained of what had once been his faith. These days, he only used Spanish for prayers and curses, an exile not only from his homeland but also from his own tongue; and the memory of that monastery between those strange rocks, where you could smell the sea on the air, and where the hillsides were filled with the sounds of the practicing choirs, was one that made the cold seem even more severe. He sneezed and looked gloomily into the flames.

This sickness had happened before, and he knew it was not serious. He had learned to endure much worse cold during those crystalline winters in Moscow when Félicité, wrapped in furs, her cheeks red as apples, would put her small gloved hand in his, and they would walk through the streets nodding to acquaintances and admirers. She had been the brazier at which he had warmed himself for those years in Russia, and despite her small frame, he had believed then that her body could provide fuel and warmth enough for the remainder of his life, were it not for the others who, his jealous eye had already long noted, clamoured to steal a bit of that same warmth for themselves.

He had endured much worse, and yet this late autumn damp, without Félicité to make him warm broth and to put her arms around him and to reassure him that the sickness would not last, was insufferable. Their journey back from Moscow had been frigid, despite the clear and generous sunshine that is peculiar to September and that had blessed them for every mile of the way. It had been so different from the journey they had taken together from London to Moscow three years before, cuddling in the back of the coach, giggling in lodging houses, when he had been astonished at her youth and her beauty and the suppleness of her body.

He heard a knock at the door. It opened before he could say anything. He hoped it might be Félicité, for he had not seen her for several days; but instead it was Antoine Meissonnier, dressed immaculately, an urbane smile that was impossible to read on his face, and a sheaf of papers underneath his arms. The sufferer sneezed again.

“Ferdinand,” said the visitor. “You are still sick?”

Ferdinand sneezed again by way of assent.

“I trust that Félicité looks after you well.” There was a kind of flicker in his smile that made Ferdinand uneasy.

“Very well, thank you,” he said.

“She is acclimatising to Paris again, after so long away?”

“I believe so. Antoine, please, sit down.” Ferdinand indicated to a chair.

Antoine arranged himself in the chair carefully, crossing his long legs. “I have brought the proofs,” he smiled. “Would you care to take a look?”

Ferdinand reached out from underneath the blanket and took the papers. He looked through, nodding as he did so.

“Of course, you will want to examine them more carefully when you are not so inconvenienced by illness, but you should find everything is in order. It is, if you do not mind me saying, a fine collection. A first-class collection. I am particularly moved by the Opus 28. It was written, I presume, in Moscow?”

“Torzhok,” the other man said. “We spent several days in Torzhok. They embroider the most beautiful figures out of gold. I bought a dress for Félicité to wear. We walked along the river in the sunshine under the willow trees…” The memory seemed to precipitate him into a fresh bout of melancholy and he shuddered pathetically, his teeth chattering together. “Antoine,” he said after a few moments, regaining a sense of his composure, “may I offer you brandy?”

“No, thank you,” Antoine smiled. “It is still early.”

“You do not mind if I do?”

“By all means.”

He placed the papers down on a table, slipped off the cocoon of blankets and got to his feet. Antoine suspected that he was afflicted more by sadness than by the cold that was causing him to sneeze, and as he watched the sick man pour himself a brandy, he wondered at the precise reason for this gloomy humour. Ferdinand drank the brandy standing up, then he returned to his chair by the fire and enshrouded himself once again in the blankets. Antoine looked out of the window. The rain was easing a little. “I should be departing,” he said. “I only wished to bring you the proofs for your approval. It is, as I have already said, magnificent work.” He smiled with his teeth but not with his eyes.

Ferdinand propped his head on his hand. He could feel the hot brandy as it burned somewhere half way down his throat.

“You are performing tonight?” Antoine asked.

Ferdinand nodded. “Will you be there?”

Antoine looked apologetic. “I am a busy man, Ferdinand. I have an appointment to keep, so I will not be present. But I wish you well. I hope that the performance is a success.” He got to his feet. “I should depart,” he said. “Goodbye.”

Ferdinand opened his eyes and looked up. “Goodbye,” he said.

When Antoine had left, Ferdinand coughed for a while, as if he wished to remind himself that he was still ill, and then he pulled the papers towards him and placed them on his lap. He started to leaf through the pages. Opus numbers twenty-four to twenty-nine. He turned to number twenty-eight and looked through the music. Antoine was right: it was magnificent. He started to hum, following the lines of the staves with his eyes.

The composer turned the pages of the proofs and hummed through the variations. Outside the window the rain continued to come down in sheets. Somewhere not far away, the composer’s publisher, the estimable Antoine Meissonnier of the Boulevard de Montmartre, went hurrying through the streets on his way home.

As the afternoon wore on, the sick man (let us not call him a malingerer, for not knowing the condition of his soul, we would be unwise to sit in judgement upon him) tired at last of sitting by the fire which had begun to burn down in the grate; and so he got to his feet and, taking the sheaf of papers left by Meissonnier, he walked to the next-door room, where his guitar lay upon a couch. He picked up the instrument and slumped into the seat, swinging his feet up, so that the guitar was laid across his belly. With the flesh of the thumb of his right hand, he stroked the strings. He deplored the barbarism of Aguado, convinced that the touch of soft flesh on the strings better suited the intimacy of the salon. To play with the flesh or with the nails? The difference was like that between a harpsichord and a pianoforte. So with the bare flesh of his thumb, he played the opening phrases of his Opus 28. He stopped before he even reached the theme.

What terrible weather, he thought.