Supernatural Sound: Science and Shamanism in the Arctic

Toolemak’s voice

Scanning the horizon off the coast of Greenland in 1822, William Scoresby witnessed the impossible: floating in the sky was an upside down ship. “It was,” the whaling captain wrote, “so well defined, that I could distinguish by a telescope every sail, the general rig of the ship, and its particular character; insomuch that I confidently pronounced it to be my father’s ship, the Fame.” And this despite the fact that no ship was visible upon the water itself.

“I was so struck with the peculiarity of the circumstance,” Scoresby noted, “that I mentioned it to the officer of the watch, stating my full conviction that the Fame was then cruising in the neighbouring inlet.” Scoresby was correct: the airy phantoms not only resembled his father’s ship but, like the supernatural images seen by those with second sight, were premonitions of it. Scoresby senior’s ship subsequently appeared over the horizon, floating the right way up on the sea.

In the same year, the captain of a Northwest Passage expedition found his ears playing even stranger tricks than had Scoresby’s eyes. Meeting “a few male wizards,” among the Igloolik, George Lyon invited their “principal,” named Toolemak, to demonstrate his magical skills:

[He] began turning himself rapidly round, and in a loud powerful voice vociferated for Tornga with great impatience, at the same time blowing and snorting like a walrus. […] Suddenly the voice seemed smothered, and was so managed as to sound as if retreating beneath the deck, each moment becoming more distant, and ultimately giving the idea of being many feet below the cabin, when it ceased entirely. His wife now, in answer to my queries, informed me very seriously, that he had lived, and that he would send up Tornga. Accordingly, in about half a minute, a distant blowing was heard very slowly approaching, and a voice, which differed from that at first heard, was at times mingled with the blowing, until at length both sounds became distinct, and the old woman informed me that Tornga was come to answer my questions. I accordingly asked several questions of the sagacious spirit, to each of which inquiries I received an answer by two loud claps on the deck, which I was given to understand were favourable.

At length, the “voice gradually sank from our hearing,” Lyon related, only to be replaced by an “indistinct hissing” that reminded him of

the tone produced by the wind on the bass chord of an Aeolian harp. This was soon changed to a rapid hiss like that of a rocket, and Toolemak with a yell announced his return. I had held my breath at the first distant hissing, and twice exhausted myself; yet our conjurer did not once respire, and even his returning and powerful yell was uttered without a previous stop or inspiration of air.

What Lyon witnessed was an Inuit shamanistic performance. Typically, these performances took place within a specially erected tent or hut, the unnatural shaking of which formed part of the uncanny effect. Lyon recorded the ceremony, as he did many Inuit practices, with an unaffected curiosity that allowed him to be drawn further into Inuit culture than most white visitors. His journal suggests that the Inuit recognized his open-mindedness and engaged with him more closely than with any of the other members of the expedition.

Lyon and Scoresby had more than their northerly location in common. Both men were startled by their Arctic encounters because they were unable to demonstrate the origin of the strange events in terms of natural law. And in this they were, unwittingly, perpetuating a tradition in which the Arctic and its inhabitants stood for the strange, the sublime and the supernatural. Since time immemorial seamen had encountered the supernatural on their northern voyages: they were wooed by mermaids, menaced by kraken, whirled into maelstroms, pursued by Flying Dutchmen.

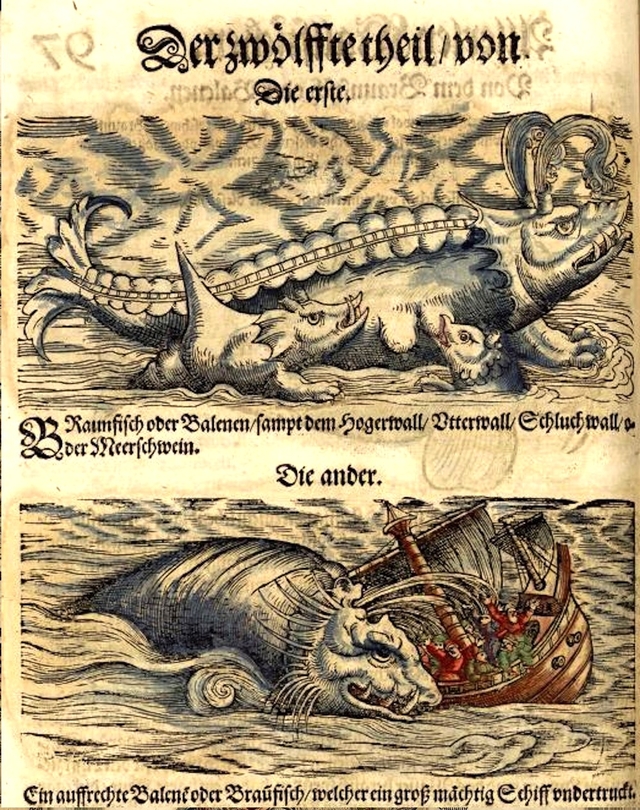

Images of kraken, monstrous whales, and “leviathans” proliferated in early modern bestiaries. This engraving is from Konrad Gesner’s Fischbuch, Der zwölffte theil von de Meertheire (1598), fol. 97r. Wikimedia Commons

These encounters were at best the stuff of myth—images of an oceanic uncanny accruing to all who had sailed in strange seas. But Scoresby and Lyon were no ancient mariners, no gullible deckhands. They belonged to a new generation of explorers, who, from the 1770s onwards, observed the seas with eyes trained in mathematical mensuration and armed with scientific instruments—telescopes, compasses, sextants, chronometers. This generation could, for the first time in history, accurately plot their longitude as well as their latitude. They were scientific voyagers, educated to turn unknown seas and unmapped shores into the calibrated lines and accurate figures of the naval chart. Careful, empirical, rational, they were not given to believing in ghosts or observing superstitions.

It was all the more significant, then, that such men reported these uncanny auditory and visual phenomena when they voyaged in polar regions. Georg Forster, the highly educated and skeptical man of science who accompanied Captain Cook on his cruise into Antarctic waters, noted incident after incident in which nature offered staggering sights and sounds: “long columns of a clear white light, shooting up from the horizon to the eastward, almost to the zenith, and gradually spreading on the whole southern part of the sky.” Nothing fitted expectations; perspectives were scrambled: “we saw the sea luminous at night”; “we passed by a large island of ice, which at that moment crumbled to pieces with a tremendous explosion”; “the ice is not always entirely white, but often tinged, especially near the surface of the sea, with a most beautiful sapphrine or rather beryline blue.”

So too the Arctic: with six months of light and six of dark, with all-blanketing white-outs in which ground and sky were indistinguishable, with compasses useless near the Pole, the region seemed a zone where nature’s laws were suspended, where the senses were overwhelmed by the unexpected.

Visible science and supernatural sound

The Arctic was a zone of the uncanny because the supernatural was increasingly banished from realms closer to home by exactly the kind of scientific and technological culture to which modern navigators themselves adhered. The Arctic’s indigenous people fascinated British travelers because of their very obliviousness to the empirical, rational, scientific culture to which ‘civilized’ Britons were committed. Far from studying this dichotomy, many scholars of Native American culture in the Arctic have simply perpetuated it without questioning the relationship of their own work to earlier white idealizations of people who seemed to exist beyond civilization.

Arctic Indians stood at the inflection point of early nineteenth-century culture—the point at which scientific rationalists and their Romantic opponents articulated their opposition to each other and yet revealed their mutual dependence. In other words, Indians came to voice the persistence of a supernatural beyond the proliferation of texts (mathematical, cartographical, statistical, literary) that claimed to comprehend nature.

In the Romantic era, science had demystified the senses, sight especially. By the early 1820s, the disciplines of surgery, instrument-making, and physics had advanced enough to enable anatomists and oculists to conduct experiments which changed our understanding of the way we see. After Thomas Young and Charles Bell’s work on the eye, vision became a subject for anatomical analysis rather than religious inquisition. If it showed unfocused, elusive spirits, these could be understood as flaws in the eye or brain, medical conditions rather than an actual perception of supernatural beings.

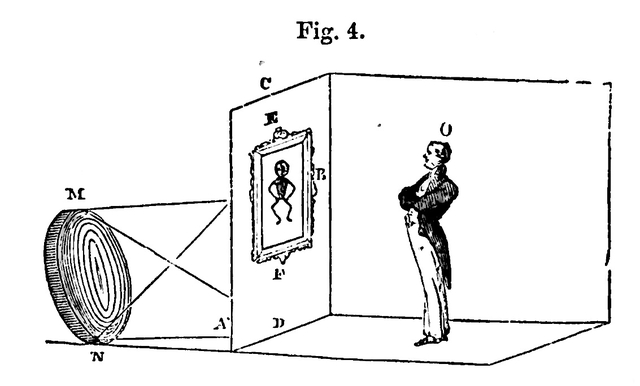

It was the application of technology, as much as the science of optics itself that removed the supernatural from the enlightened world. But technology also conferred an unparalleled ability to manufacture the supernatural. By the 1820s, engineers had constructed a series of vision-machines capable of producing ghosts at the turn of a handle such as the phantasmagoria—essentially an updated and moveable magic lantern capable of projecting magnified images through a gauze screen into smoky air. The images grew and shrank in size and fluttered as the air moved: they seemed, like spirits, to have animate life but no material substance. In 1833, David Brewster, by now the foremost scientific expert on optics, designed an improvement to allow the phantasmagoria to project not just images painted on glass, but also reflections of the living human body. Flesh could now become spirit with the aid of smoke, mirrors, and the latest precision lenses.

In 1832, Brewster published his Letters on Natural Magic—a book dedicated to demonstrating how many of the encounters that had once been thought to be supernatural were now explicable as being purely natural. Paradoxically, this demystifying work related many stories of hauntings and miracles, as if Brewster, despite his intention of explaining them away, was swayed by their narratives of belief in a world that could never be ultimately reduced to empirical facts. Brewster’s ambivalence about the supernatural was apparent in his discussion of the Arctic: he related at length Scoresby’s vision of ships in the air only to explain it away as a manifestation of natural law. Scoresby’s polar miracle was, in fact, only a mirage, now explicable by the latest experiments, demonstrated with mathematical formulae and geometrical diagrams. No longer did the Arctic defy scientific authority as it did the evidence of the senses. Its visions were reducible to abstract knowledge, number-relationships illustrated by nothing more sensual than a series of angular lines.

An illustration from Charles Brewster’s Letters on Natural Magic. Internet Archive

Yet as vision grew increasingly technologized, the Poles became landscapes in which a different kind of supernatural encounter persisted—an encounter dependent on a sense that was not yet subject to mechanical reproduction and mathematical explanation: the sense of hearing. Sound, whether inarticulate noise or articulate voice, was hard to pin down. Its origins, movement, and reception were difficult to fix and had not yet been captured by technology—as the phonograph and telephone were still nearly a century in the future.

Not just sound, but indigenous people’s use of it, fascinated Victorians because they defied scientific explanation. Thus it’s notable that, as his chief example of the haunting power of sound, Brewster chose none other than Lyon’s account of his encounter with the Inuit shamans who ventriloquize the voices of the spirits—reproducing it in full. Even for this arch-scientific explicator, then, the encounter with the Inuit shaman testifies to sound’s power to elude the knowable—and contains an attraction to and fascination with the supernatural.

This is what Brewster says:

The ventriloquist … has the supernatural always at his command. In the open fields, as well as in the crowded city—in the private apartments, as well as in the public hall, he can summon up innumerable spirits; and though the persons of his fictitious dialogue are not visible to the eye, yet they are as unequivocally present to the imagination of his auditors as if they had been shadowed forth in the silence of a spectral form.

For Brewster the haunting by voices is an illusion—a ventriloquism, but he writes as one who is convinced by it. The spirits are summoned. The speaking persons are present to the imagination. And so the Inuit shaman is a talismanic figure because he marks the limit at which scientific demystification—a logical, textual discourse—breaks down, precisely because the shaman’s oral powers defy the explanatory resources of scientific method. The scientific mind knows it can’t be real yet believes anyway.

In fact Brewster’s text and Lyon’s narrative testify in their form as well as in their content to the capacity of the oral/aural to elude them and the kinds of knowledge they epitomize. Effectively, Brewster and Lyon, following several earlier visitors to the Arctic Indians, write a demonstration of their inability to grasp, in their most powerful technologies (the textual technologies of measurement and record), the Arctic natural world vocalised by the shaman. In the process, they reveal both their bewilderment at the ineffectiveness of their technologies and their fascination by people who are not governed by such technologies.

To such Britons it seemed that the voices uttered by the shaman, because they were seemingly without body yet inhabited a body not their own, called his presence into question. It is as if what became manifest in the body of the shaman was the condition of all voices—an unfixable, mobile sound that moves through, but is not wholly possessed by, a body.

Apprehended in the shaman’s body, the voices that speak through him seemed like the essence of speech/sound—articulated spirit, passing into and out of body. For an observer educated, like Lyon and Brewster, in the European tradition, this voice is analogous to the Muse occupying the poet (vates), or the god occupying the prophet (Cassandra)—a matter of inspiration. Thus the Inuit becomes a present-day example of a figure confined, in enlightened countries, to the past (or to the uneducated)—the figure of the prophetic oracle. For the Indians, however, the shaman mobilizes the voices of the spirits who animate the natural world—plants, rocks animals, sea, sky, storm—and the spirits of the dead. By so doing, he demonstrates his access to a real spirit world, enabling him to interpret dreams, predict future events, and cure the sick. In both traditions, then, the shaman accesses power via possession. He becomes uncanny, a double presence: he is at once himself and more than himself.

This uncanniness made the shaman enthralling for many of the voyagers and men of science who visited the Arctic. Although as late as 1750 very few Britons had come into contact with Arctic peoples, by 1830 a succession of travelers had described both the Inuit and the ‘northern Indians.’ Most of these travelers were employees of the Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC)—traders who lived among the Cree and Ojibwa Indians in northern Canada; some were trappers who dwelt among the Inuit on the Labrador coast; a few were, like Lyon, polar explorers who met native people who came out to trade with the white men’s ice-bound ships.

All of these Britons were intrigued by the shaman, who became one of the chief figures about whom they commented in their journals. When those journals were published as travel narratives, they established ‘Eskimos’ and ‘northern Indians’ as oracular, sublime, ‘prophets of nature’ in Britons’ imagination—as well as ‘primitives.’ These writings thus shaped Indians in a rather different popular image from the images attached to more southerly Native Americans with whom white colonists had had centuries of contact (stereotypes including drunken savages, brave warriors, noble innocents).

One witness was the HBC trader George Nelson, who had more than twenty years’ experience of working with the Cree and Ojibwa. In a journal composed in 1823 at Lac La Ronge (Northeast Saskatchewan), Nelson recorded his profound “astonishment” at the sights and, most of all, sounds of the shamans in the shaking tent ceremony:

The rattler is shaked at a merry rate and all of a Sudden, either from the top or below, away flies the cords by which the Indian was tied into the lap of he who tied him. … It is then that the Devil is at work—Every instant some one or other enters, which is known to those outside by either the fluttering, the rubbing against the Skins of the hut in descending (inside) or the shaking or the rattler, and sometimes all together. When any enter, the hut moves in a most violent manner—I have frequently thought that it would be knocked down, or torn out of the Ground.

In 1795 a still stranger account of Indian shamans was published—Samuel Hearne’s A Journey from Prince of Wales’s Fort in Hudson’s Bay to the Northern Ocean. Hearne was an employee of the HBC who in the early 1770s, led by a party of Cree and Dene, walked through the Canadian interior to the Arctic shore. The only white man in the expedition, Hearne was dependent upon his companions for survival, following their lifeways and directions rather than vice versa. From this position, he lauded the power of shamans’ oral performances, revealing a society from which belief in the supernatural had not been banished in the name of science and civilization.

Hearne revealed that the shamans mobilized spirits to cure and curse their fellow tribe-members:

When a friend for whom they have a particular regard is, as they suppose, dangerously ill, … they have recourse to another very extraordinary piece of superstition; which is no less than that of pretending to swallow hatchets, ice-chissels, broad bayonets, knives, and the like; out of a superstitious notion that undertaking such desperate feats will have some influence in appeasing death, and procure a respite for their patient.

Reading Hearne in 1797, Samuel Taylor Coleridge was fascinated by his account of shamanistic practices and the belief these practices engendered among the Indians. Hearne prompted him to write poetry that defers to the oral, as if tracing a passage of sound too elusive to be caught on paper—what he called “strange power of speech.” In this poetry he sought to make the supernatural encounter believable for his readers, to turn them away from too materialist a culture. Coleridge explained that

I had been reading … Hearne’s deeply interesting anecdotes of … workings on the imagination of the Copper Indians … and I conceived the design of showing that instances of this kind are not peculiar to savage or barbarous tribes, and of illustrating the mode in which the mind is affected in these cases.

A new sonic aesthetic: Coleridge, orality and Arctic shamanism

The Arctic as a space of supernatural wonder, as depicted in Gustave Dore’s 1876 engraving of Coleridge’s epic. Wikimedia Commons

Coleridge’s interest in Hearne was both psychological and cultural. He wanted to remind his educated readers of the power of imagination—of what they dismissed, when they encountered it among uneducated peasants, as superstition. Because its effects among the Indians and Inuit were so startling and so novel, they were less likely to be so dismissed. For Coleridge it was sound more than sight, and, in particular, the sound uttered through the shaman, in which the supernatural could be credibly apprehended—or rather, through which enlightened readers could access the belief that the occult manipulation of voice embodied by the shaman does indeed give them spiritual power.

‘The Rime of the Ancyent Marinere,’ Coleridge’s greatest poem, was written after his exposure to Hearne. The polar region, as Coleridge’s mariner describes it, resembles Hearne’s (as well as Forster’s and Cook’s) in that it is a place of unaccountable phenomena that defy mensuration—especially of mysterious sounds:

The Ice was here, the Ice was there,

The Ice was all around:

It crack’d and growl’d, and roar’d and howl’d—

Like noises of a swound.

(lines 57-60)

The sonic uncanniness of the Antarctic—a place at the opposite pole to enlightened, domesticated, and charted Britain, a place escaping the scrutiny of science’s visual technologies, prepares Coleridge’s readers for the later emergence of the supernatural in the form of voices emanating from sea and sky. The zombified crew, for instance, utter sounds that are their own and more than their own, sounds profoundly disturbing in their abnormality. They seem like shamans—voicing spirits who utter through, but are not circumscribed by, the body:

Sweet sounds rose slowly thro’ their mouths

And from their bodies pass’d

Around, around flew each sweet sound,

Then darted to the sun:

Slowly the sounds came back again

Now mix’d, now one by one.

(lines 341-346)

Intriguingly, the elusiveness of these sounds is produced in visual terms—we see them flying like birds—although sound, obviously, is always invisible. By describing sounds thus, Coleridge asks us, as readers, to see what we have no experience or possibility of seeing, thereby causing us to doubt both the separateness of the senses and their efficacy in comprehending the phenomenal world.

By the climax of the poem, sound is the chief mode through which the supernatural is encountered, precisely because it cannot be fixed or calibrated and because the reader cannot simply translate it into a more measurable form of data. The mariner is as overcome by its power as were the Dene who, hearing the spirits voiced through the shaman, fainted and wasted away:

The Boat came closer to the Ship

But I ne spake ne stirr’d!

The Boat came close beneath the Ship,

And strait a sound was heard!

Under the water it rumbled on,

Still louder and more dread:

It reach’d the Ship, it split the bay;

The Ship went down like lead.

Stunn’d by that loud and dreadful sound,

Which sky and ocean smote:

Like one that hath been seven days drown’d

My body lay afloat; …

(lines 575-86)

Matching its form to its content, ‘The Rime of the Ancyent Marinere’ offers itself as a vindication of an oral culture. Still apprehended by indigenous Americans and uneducated villagers, that power would, harnessed in Wordsworth’s and Coleridge’s new poetry, give their readers a taste of what their commitment to materialist culture deprived them of. It would alert them to the sensory and spiritual deprivation that this culture enforced in the name of measurable knowledge—and thereby puncture their complacent participation in that culture.

In this respect Native Americans were vital figures in the development of a revolutionary new aesthetic—a sonic aesthetic in which orality was both supernatural subject-matter and the ostensible mode of artistic delivery: Wordsworth and Coleridge made their poems as ballads to be spoken, sang, and chanted. This sonic aesthetic had spiritual and perceptual revolution as its aim and Indians at its root, as Blake acknowledged when, in The Marriage of Heaven and Hell, he paid tribute to “the North American tribes” who “practise … raising other men into a perception of the infinite.”

The Romantic shaman was a new, anti-Enlightenment figure shaped by what scientific travelers guiltily half-revealed: he was uncannily desirable as well as alien because his voicings delimited the explanatory power of science. This process had consequences for real, as well as poetic indigenes: making the northern Indian and the Inuit uncanny figures conditioned the way Indians were seen not just by nineteenth-century poets but also by twentieth-century anthropologists (there was far greater interest in shamans than, for instance, in Inuit women, and in ritual than in domestic work).

In short, the process shaped Romanticism in Britain but also romanticized, for both poets and scientists, the Arctic into a zone of exotic otherness. It became a place beyond empirical grasp: the real/fantasy land of orality about which those living within the textual horizon of rational empiricism dreamed with fear and longing.