“To Wait Together upon the Lord in Pure Silence”

“Vague Religious Feeling,” “Upward Rush of Devotion,” and “Response to Devotion,” illustrations of mental states from the 1901 book Thoughtforms, by Annie Besant and C. W. Leadbeater.

“The voices of the past are especially lost to us. The world of unrecorded sounds is irreclaimable, so the disjunctions that separate our ears from what people heard in the past are doubly profound.”

When historians say they hope to retrieve the “lost voices” of the past, they typically mean that they wish to uncover the lives of people who did not leave behind written records. Historian Leigh Schmidt, however, reminds us that when we talk about historical voices, we can also refer to actual voices. The past was full of sights and sounds that we can only imagine. Yet if the sounds of the past are “lost to us,” how much more are the silences? How did people of the past experience silence? In the history of the United States, one group in particular spent a lot time thinking about and practicing silence—Quakers. Because silence was so integral to their worship, Quakers, or Friends, can help us understand how some people experienced silence. They can also illuminate how religious communities use their understanding of what constitutes appropriate religious sound to define themselves.

Quaker worship services have always consisted of long periods of silent reflection. In the late eighteenth century they faced challenges to their silent practice from the rapid growth of new evangelical groups, such as the Baptists and the Methodists. Indeed, as Friends ministers encountered the ecstatic, emotional worship services of Methodists, they began to define their practice of silence not only in traditional Quaker terms, but in opposition to these evangelical groups. Whereas Quakers perceived their own worship as reflecting godly silence, they believed that Methodists’ loud, noisy worship would lead them astray from the true guidance of the Inner Light, or the Holy Spirit. Quakers believed that such noisy behavior had no place in the true Christian community.

Late eighteenth-century Quaker ministers’ journals reveal that, for them, “silence” meant more than the simple absence of speech or singing that characterized their worship services. Silence also referred to an internal condition—one that minister Job Scott described as a “silent introversion and feeling after God.” Scott’s contemporary Elias Hicks explained that silent worship was most effective “when the mind is silently prostrated at the throne of grace, and helped to be sequestered from all intruding thoughts, and wholly centered in and upon Jehovah.” True experience of silence occurred only when the individual experienced “entire sequestration from everything of an outward or external nature.” Only then would his or her soul be “permitted to enter into the holy place.”

Silence, then, required Quakers to quiet not only their voices, but their minds as well. Silence could also refer to a lack of speech—the result of individual, silent practice. Scott explained that he sometimes “felt great caution not to move in words”—not to speak during worship—“unless a fresh opening induced me”—unless he felt certain that the Light inspired him to speak. He believed that ministers were “often closed up in profound silence by the outward expectations of the people, not having liberty … to gratify those itching ears.” In other words, ministers were in fact prevented from speaking, because the people around them expected to hear something that the Spirit did not want them too. Priscilla Hunt reportedly described this phenomenon as “something cast in my way … whereby the pure flowing of gospel communication is obstructed.” Hicks believed that sometimes it was the minister’s responsibility to set the example of “silence” to other Quakers by refraining from speaking, if he did not feel genuinely moved by the Light to speak.

The ministers’ experience of silence was also sometimes painful—as though it were a palpable absence of God. Scott in particular recalled many instances in which an extended period of “silence,” meaning lack of communication from God, became emotionally distressing to him. In December 1779, he visited a number of families in Dartmouth. He reported, “It was a time of great trial: I was shut up in silence, pain, and poverty of spirit … .” He persevered in visiting families in the area, but “still for sometime found no relief,” because the Light did not communicate with him for weeks. Eventually, however, his “tongue again was loosed,” and his “confidence” was “renewed.” For Scott, God’s “silence”, or lack of spiritual communication, could be incredibly emotionally taxing because of his fear that God might never “speak” to him again.

In addition to internal practices of silence, however, Friends in the late eighteenth century defined silence in opposition to the behaviors they observed of both Baptists and Methodists. Quakers objected to these groups’ worship services because of their tendency to wordiness and speeches. Even though he had been raised in the Society of Friends, Scott went through a rebellious period in which he attended Baptist services. He explained that when he was young, he attended Baptist worship services because “Friends meetings were oftener held in silence than suited my itching ear.” He “loved to hear words,” especially on “doctrines and tenets of religion,” and “the Baptist preachers filled [his] ears with words, and [his] head with arguments.” As an adult, however, he returned to the Quaker church, because all of those words at the Baptist meetings failed to touch his “heart.” In 1790, Hicks visited a group of former Friends in Vermont. He recalled that they had initially been “convinced of the principle of the Inward Light.” Over time, however, they had abandoned “the principle of Divine Light and Grace.” Instead, “those who apprehended it their duty to teach had got too much into words and speculative preaching and doctrine—which soon produced discord and a schism among them.” According to both Hicks and Scott, silence meant that people did not become enamored with hearing words but instead kept quiet. This silence was necessary in order for them to experience genuine, personal connection with the Holy Spirit. Only true spiritual communion with the Spirit could provide the truth, and Friends were not supposed to rely on others’ words but their own experiences.

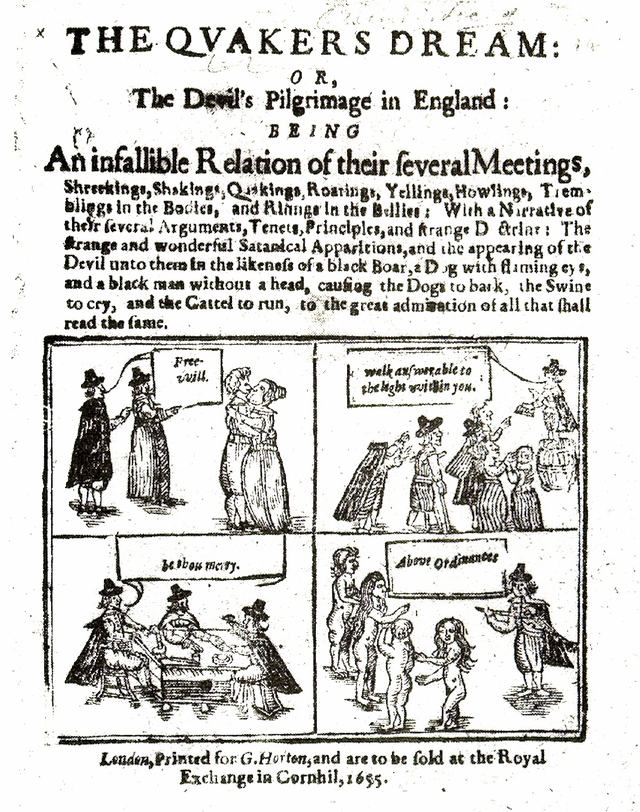

The Quakers were originally associated with noise, not silence: this 1655 pamphlet attacks their supposed “Shreekings, Shakings, Quakings, Roarings, Yellings, Howlings, [and] Tremblings in the Bodies.” The accompanying woodcut shows Quaker women parading nude and a kissing couple, amongst other sins. Wikimedia Commons

Even more disconcerting to Friends, however, were the Methodists’ “noisy” worship practices. In 1797, Hicks reported that a joint meeting of Friends and Methodists in Saint Michaels, Maryland went very well, except for the presence of one man who made “loud groanings” while another Friend was speaking. As he sat in silence, Hicks felt inspired to stand up and inform the group of people there of “the hurtful tendency of such inconsistent conduct”—the groaning—and he encouraged them to practice “stillness” in worship meetings.

Scott was less put off by this behavior than Hicks, but he still believed that noisy worship would lead the Methodists astray. In 1788, he attended a meeting at which the Friends met “mostly among such as were not of our society, many of them called Methodists.” He explained positively that “some of their hearts have been touched with a life coal from the holy altar.” He saw in their excited form of worship a genuine connection to the Holy Spirit. He was nevertheless troubled because they seemed “very unsettled, many having hurried forward into much religious activity, being very noisy, talkative, and almost if not quite ranting.” He believed that their energetic worship practices distracted them from “the truth,” but he remained hopeful that they would “finally shake off their religious exercise,” which indicated a hasty entrance “into religious performances without the pure leadings of truth therein.” Scott implied that Quaker silence demonstrated the patience necessary for a true communion with the Inner Light, rather than the distraction of the physical demonstrations of Methodist worship.

For some Quakers, even being in the tumult of a Methodist worship service caused great uneasiness, because their style of worship felt wrong. On one occasion, Joseph Hoag attended a service in a Methodist meetinghouse. He was immediately uncomfortable there, because the Methodists invited him to preach from a pulpit, which Quakers did not use. At first he concluded that he “could not open [his] mouth,” because of the inappropriateness of the setting. After sitting in silence for a while, however, he felt “the Word of Life to arise in [his] mind,” and he decided to speak to them. Initially “there was considerable whispering over the meeting,” but he claimed that “the first sentence spoken stilled them.” Despite his perception that “Truth reigned” during the meeting, when it ended he “felt a caution to take care not to be drawn away by the affections of the people.” Instead, he left immediately to stay with a Friend who lived nearby, “away from all the noise.”

Just as Quaker ministers cautioned against worship services that emphasized wordy sermons, they warned against the noisy bodily demonstrations of Methodists and other evangelicals, because they distracted from the Inner Light’s ability to touch their hearts. Scott described several meetings with Methodists in 1788. Though at times he was encouraged by their occasional silent behavior during worship, more frequently he observed their noise. He explained that he attended many meetings with Methodists and Baptists during his trip to the south. He felt kinship with them, because their “societies” were in their “infancy” and their spirit was “near to [his] life.” He worried, however, that they were “in imminent danger of being stifled by a multiplicity of lifeless performances.” In 1793, Hicks argued that “true worship” would not reflect “the fruitlessness of mere bodily exercise in our religious performances.” These practices, he claimed, were meaningless without “quickening virtue of the Word of Eternal Life influencing and assisting the soul in that solemn act.”

In the late eighteenth century, one religious group’s “noise” could be another group’s passionate expression of religious fervor. Where one group saw “lifeless” physical exercises, another witnessed powerful spiritual expression. Quakers understood themselves as a “silent” people in contrast to the behaviors of their contemporaries, like the Methodists. They defined silence not only by their own practices but by comparing themselves to others: silent, and therefore genuine, worship was not present in the loud, noisy, ecstatic Methodist meetings. Thus, through their experiences with Methodists, Quakers reinforced their own group identity as a people who did not make noise during worship. Methodists, by contrast, used ecstatic worship practice to gain and consolidate a community, attracting a steady stream of new converts. In either case, the community’s relationship to holy sounds—whether silent or out loud—was essential to defining who belonged.