Curculionidae: Scolytinae. A Parasitology of Sound

The following text is an example of the kind of entry I would like to include in a Bestiary of Sound that I am currently working on. The idea of the book comes from medieval and early modern bestiaries, many of which contain descriptions of the most fantastic, never-seen or not-yet seen creatures. Often lavishly illustrated, these works appealed to early modern readers’ sense of the marvelous, but they also encouraged them to do something profoundly modern: to take risks in the pursuit of the unknown. My own bestiary is a similar attempt to establish the most unlikely of connections between organisms, things, and sounds in hopes of thinking about the world in novel ways. Like the entry on the bark beetle below, all entries are structured around the idea that in order to represent sound as a cultural form, we must evoke more than an acoustic version of established master narratives.

The notion that seemingly simple acoustic phenomena—the sound of a voice, a chord—might be useful in clarifying otherwise obscure matters is among humankind’s oldest. From a divine utterance that brings the world into existence in the Judeo-Christian tradition or the cosmology of the West African Dogon to the vibrating membranes of string theory—the universe is made of sound.

Yet sound can also function in a very different kind of epistemology, one that resists the urge to explain complexity by tracing it to a first cause, as in Laplacean physics, Cartesian rationalism, or Kantian idealism. An example of this is the entomological study of climate change: the study of how the environment is shaped not by humans but by beings like the small insects of the Curculionidae: Scolytinae species, commonly known as bark beetles.

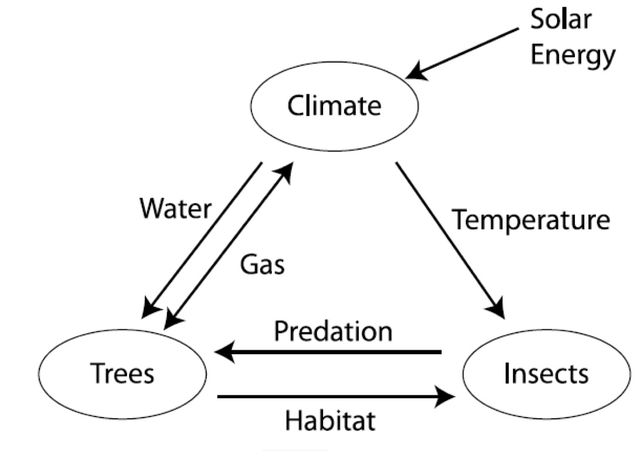

Bark beetles have long been suspected of posing the single most daunting threat to the boreal forests of North America and Siberia. Researchers also know that much of the massive spread of these humble creatures is due to climatic factors. Prolonged periods of drought caused by global warming render these forests susceptible to infestation. The ensuing deforestation in turn releases enormous amounts of CO2, which had been previously sequestered by healthy trees. This, in turn, increases the greenhouse effect, which creates favorable conditions for rapidly growing populations of insects, which infest more trees, which … . A perfect feedback loop that composer David Dunn and theoretical physicist James P. Crutchfield picture thus:

Yet feedback loops are more than self-reproducing systems. They tell us two things: first, new patterns of behavior are not owed to the actions of single agents as much as they emerge from the interaction of several actors. Second, complex interactions such as the bark beetle-climate change loop are inherently unstable and unpredictable. Under normal conditions they may ensure the stability of ecosystems. But by the same token such loops may also lead to situations in which even small causes may have catastrophic effects.

There have been numerous attempts to upset the loop and to bring beetle infestation under control through pesticides and pheromone traps. So far these initiatives have met only with partial success. Yet more effective strategies against deforestation and resulting climate change may soon become available. The bark beetle, Crutchfield and Dunn argue, possesses remarkable bio-acoustic capabilities that might contain the secret to combatting beetle infestation. Some varieties of bark beetles, such as the North American pinyon ips (Ips confusus), are equipped with a sound-producing organ located at the back of the insect’s head and that is activated by means of a plectrum on the underside of the prothorax. While we may reasonably assume that the beetles use the clicks they produce in this manner in order to coordinate attacks on trees, their bio-acoustics are part of a far more complex feedback loop. With the help of specially designed “microphones” that are inserted into the trees, Crutchfield and Dunn found that decaying cells of dying trees produce acoustic emissions in the ultrasonic spectrum. Bark beetles, they speculate, might “hear” these sounds and decode them as meaning “food.”

If there is any merit to this hypothesis—and it is a hypothesis after all—our feedback loop would have to be expanded by more than an additional acoustic factor. Since communication systems only function within a frequency range that participating organisms can produce and perceive, the social system of bark beetles could be far more complicated than is generally assumed. Combatting climate change thus requires more than moral appeals or more efficient technologies. We need a new thinking about the boundary between man and animal. Who we are and what binds us to all the other creatures of the planet is no longer part of an overarching discourse in which animals always figure subservient to Homo sapiens.

The bark beetle may have yet another lesson in store. Sound and music may no longer be subsumed under conventional discourses of truth based in only one field of knowledge. As a parasite, the bark beetle reminds us that a new mode of inquiry is required to think about people, animals, or music in times of global climate change: a parasitology of culture perhaps. Western philosophy’s desire for certainty, for the most part, entailed the identification and suppression of the parasite, the troublemaker, and of noise; the bark beetle allows no such easy classifications. For who is the parasite here? The tree? Man? Or the beetle?

Lafontaine’s fable of the town mouse and the country mouse comes to mind here—and Michel Serres’s The Parasite along with it. In the book, the thinker of mingled bodies wonders what happens to relationships of dual exchange when the parasite enters the equation. The parasite is not a new being, it is the complete blurring of boundaries between entities: between host and guest, subject and object, cause and effect.

But also those boundaries between artist and work. The artist is a parasite of his own work that in turn feeds on him. We do not speak a language; language speaks us, as David Dunn’s extensive oeuvre shows. The San Diego-born composer has been active in sound art from as early as the 1970s. But in contrast to the appropriation of natural sounds in experimental music and sound art, Dunn sees his works as a re-contextualization of such sounds. In The Sound of Light in Trees, for instance, he correlates the acoustic “signature” of specific tree regions, the density of beetle infestation, the life cycles of trees and the condition of their phloem layers. Music thus becomes a strategy among others to preserve forms of communication akin to human language. As such, it shares certain features with the communicative forms of other species. Intelligence is not the exclusive feature of a single species, but an emergent quality of larger ecosystems comprising many species. In short, music and natural sounds are part of a feedback loop.

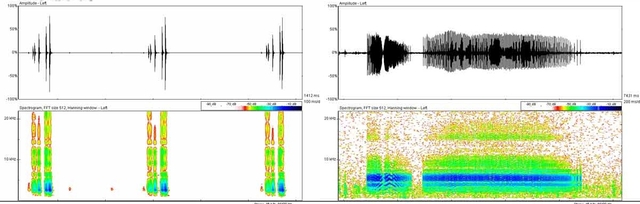

Sonograms of beetle chirps recorded by David Dunn for his field recording The Sound of Light in Trees. David Dunn

The equivalent of this microcosm of rustling leaves, wind, and beeping beetles is a tranquil, almost brittle “soundscape” whose charms do not become immediately apparent. We struggle to break through the sharp line at the heart of what we call music and that separates the animal-like, inhuman from the human. The point, according to Dunn, is not to double nature musically, as in most post-Aristotelian aesthetic thought, but to grasp the acoustic interdependence of nature and human sonic labor as part of processes that resist unambiguous attributions of sound to one or another ontology—of Man, music or nature. The difference between humans and animals is as much due to the violence we do to the latter as the differentiation between nature’s sounds and music is itself part of the mastery of nature.

Recommended reading/listening:

David Dunn:

Music, Language and Environment.

The Sound of Light in Trees. Audio CD. Earth Ear ee0513.

David Dunn and James P.Crutchfield:

Insects, Trees, and Climate: The Bioacoustic Ecology of Deforestation and Entomogenic Climate Change. Santa Fe Institute Working Paper 06-12-055.

Michel Serres:

The Parasite. (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1982).