When the Jazz Age Met the Pre-Columbian

For over two hundred years, from about 900 CE to 1150 CE, the Pueblo people made their home in Chaco Canyon, making it the most impressive pre-Columbian settlement in North America. They built beautiful, expansive ‘mansions,’ apartments, and sacred kivas until drought forced their migration. The ruins’ ‘discovery’ in the nineteenth century launched years of fascination and study at the site. From 1929 to 1937, the School of American Research and the University of New Mexico hosted a summer field school there that was revolutionary for its time: Edgar Lee Hewett, the field school’s founder, lobbied for the inclusion of women. Many of those women—Bertha Dutton, Florence Hawley Ellis, Florence Lister, Anna Sheppard—went on to pioneering professional careers. Their adventures at Chaco Canyon were lastingly chronicled in a weekly newsletter called Digs.

When The Appendix learned of Digs from Erika Bsumek, one of this issue’s contributors, we knew we had to feature it for our own ‘Digs.’ Dry but crunchy, like a martini stirred with a pickaxe, Digs was edited by a student named Winifred Stamm, and is a wonderful document of its moment, when a group of college co-eds left the Jazz Age each summer to venture into the Pre-Columbian. They diary, they tease, they compose doggerel odes to the dust around them. They talk about dressing the part (bandanas were all the rage). They make fun of their fellow male students’ visiting sweethearts, the “cool pink-and-white summer girls.” They have fun.

Digs also documents the students’ relationships to the Navajo laborers who helped excavate the site. There was mutual fascination, and perhaps a little bit of anxiety. While the students dug in the dirt, the Navajo dug at the students, “worming information out of [them] by slow degrees.” The Navajo shared songs, and told stories, and the students attended their Fourth of July celebration at the Chaco Trading Post. (That night the female archaeologists were woken by a “Bang! Bang! Bang!” Had it been a “a Navajo uprising?” No, Stamm explained: just the white boys of the camp being white boys, letting off firecrackers.) For their part, the female students studied how the Navajo women looked, dressed, and acted, the “loops of turquoise” in their ears, their voluminous skirts, their strings of beads. Sometimes they learned those women’s names, and were sympathetic, but the unfortunately frequent impression the white women leave is that their Navajo counterparts were exotically dressed “daughters of nature,” whose clothes were prêt a porter.

Whether it’s so far from there to the “Navajo Hipster Panty” American Apparel was forced to stop selling in 2011, we’ll leave up to you.

[WINIFRED STAMM, EDITOR

No. 3 CHACO CANON, N. M., JULY 13, 1929]

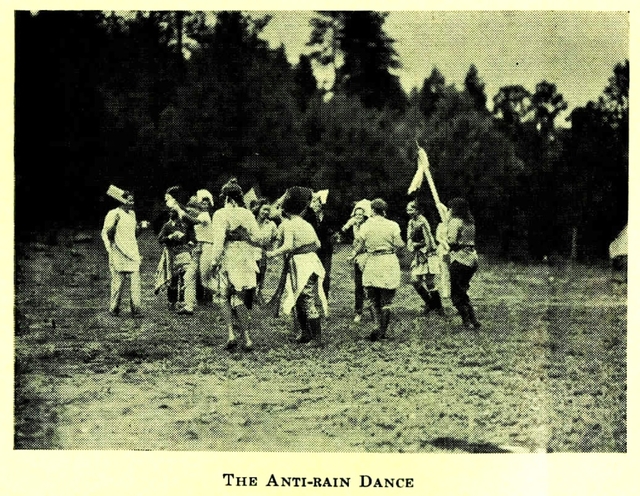

COLORFUL FOURTH BY NAVAHOS

Loud was the noise and great the confusion when four hundred Navahos rode into Smith’s store in Chaco canyon for a monstrous celebration on the Fourth of July. From all directions they came, in cars and wagons and on horseback. With children and wives and dogs - and without. Dressed in their best hats and jewelry. Such jewelry! Turquoise and more turquoise and a lot of silver. Necklaces so heavy that they burdened their weavers. Bracelets three and four inches wide - and tiny little slim ones weighted with stones. Rings in an infinity of sizes and shapes. Neckerchiefs whose colors hurt the eyes. Velvet and plush jackets. Purple and red and green. Long, long skirts swishing through the dust and big concho belts holding up dirty jeans.

The excitement started late Wednesday evening. All day they had been coming in small lots. They would pull up to the store with a flourish, climb out and join the multitude within. After due meditation and consideration they would accost Mr. Smith and request tomatoes. Mr. Smith would open a can, dump in a lot of sugar, supply a spoon, and the Navaho would sit down and devour the can. When he had finished, he would return the spoon - first carefully wiping it on his overalls - and go back to his wagon or pony and drive down the arroya to make camp. By eight o’clock the canyon - particularly in the vicinity of the store - was crowded and noisy with children and dogs and bleating goats and fires burned everywhere along the cliff. When the students of the field camp across the canyon drove over after lecture, the store was so crowded with people eating tomatoes or just standing, not conversing, but occasionally approaching one another with out-stretched hand and touching fingers, that they couldn’t get in. The [sic] were [p. 27] greeted by such a deluge of firecrackers from the youngsters that they soon beat a retreat to the other side of the bridge.

Very early next morning the Navaho camps were astir. Many more had come in during the night, and by nine o’clock their number was estimated at four hundred. They rallied round in front of the store and the powwowing began. A rancher from up the canyon took charge of the day’s program and the whole morning was spent in arranging races, making bets, and planning this and that. Every thing had to be done with seriousness and thoughtfulness and each Navaho considered deeply and long before he committed himself to anything. It was noon before they moved to the race track and the real business of the day began. Practically everyone was on horseback, though their were a few crowded cars, and there were no tourists and very few whites. Mostly Indians in their picturesque costumes sitting still on their ponies waiting for things to begin. Two rather poor races were run off. Here and there two men would be seen squatting together with their stakes between them and when the race was over, one would scoop the booty up. Many bracelets and rings of great value changed hands.

Just before two o’clock when a halt was called for dinner, the women ran a hundred yard dash. Their full skirts billowed out around them and their squash blossom hairdresses flopped and jerked. Their moccasined feet fairly tore over the ground and the finish was neck and neck. The gigglying [sic] involved was great.

…

DUST

Bang! Bang! Bang! Through the stilliness [sic] of the night. Archaeologists sit up and look startled. A Navaho uprising? Not at all, my children. Just boys who insist upon being boys celebrating the fourth a few hours previously.

It is you know, a rather odd sensation to be waked by a firecracker shot off in your water bucket.

It is also odd sensation to find one’s bed filled with shards - or so a young lady who got lost tells us. It is rather cruel of people to fill lost ladies’ beds with shards. But is very rude of lost ladies not to be lost at all, but to stroll into camp and greet their doughty rescuers with, “I’ve had the best time!”

These staircases in the vicinity are bad enough in the day time without having to climb them after dark. On moonlight nights, however ———. Ah well! Boys will be boys, and girls will be girls, and cliffs are very beautiful things when flooded with silver light.

The population of Chaco canyon has been greatly [p. 32] amused lately by the spectacle of Ye Editor entering the office each morning by crawling through a window the size of a porthole. Dr. Hewett carried the key in his pocket to Santa Fe.

Civilization is invading us! You may believe it or not, but an airplane flitted over the canyon last week. Not only flitted, but fluttered and came down low so the passengers could see the ruins. We expected to be bombed every moment.

The Admiral was very rash. He got out in the middle of the campus and fluttered a white shirt. Suppose the thing had come down! Our one excuse for cracking our necks looking at planes when we get back to where they run would have been gone. “I haven’t seen one of those for six weeks!” Another good line gone flooey!

White shirts or knickers in camp are more than ever passe. Reconstruction work on the dig has started and the puddles of adobe are huge and sloppy. Woe unto him who shall put temptation before his brethern! [sic]

Next camp we have we are going to make it a rule that commissary managers can’t import their sweethearts. At least not if those sweethearts are going to be cool pink-and-white summer girls. It is cruel and inhuman treatment to so remind us of the days when we too have worn white linen and Spanish heels and had waves in our hair.

Will we ever see a marcel again, do you suppose? Will we ever recapture those school girl complexions? And those haircuts that the young Reiter brought out from town didn’t fit at all, at all. Our men are beginning to look like poets and musicians.

…

DUST

THE SONG OF THE EXCAVATORS

I think I am a prairie dog,

That’s going down to China.

I think I am an angle worm

That’s learning how to dig.

Perhaps I am a gopher

That’s looking for its mother —

But I’m going to run a steam shovel

When I get big.

Which masterpiece was composed by Miss Tietjens of University of Wisconson [sic] as she trowelled the floor of a tunnel.

A steam shovel would have been a big help. This business of raking down a mountain of dirt, hugging it to one’s bosom, and backing out of the tunnel, while amusing, isn’t quite as effective as it might be.

Besides one always leaves one’s trousers behind when one crawls into the tunnel, and one’s shirt behind when one crawls out.

…

Mr. Palmer’s kind offer of the rooms in Pueblo Bonito for the use of the School has been enthusiastically accepted by a group of students in search of a cool place to nap. Some tourists happened in upon them the other afternoon. “Good gracious,” exclaimed one, “Do you sleep in here?” “When we don’t get interrupted,” politely replied one of the students. “But aren’t you afraid of ghosts?” shivered a second tourist. “The spiders are much more active,” said the student. “Well I wouldn’t like those so very well either, but I sure wouldn’t sleep in a place as full of dead Indians as this one.”

The students spent fully three minutes trying to convince her that the Indians were so completely and entirely dead that even their graves are lost, but she couldn’t see it and went off shaking her head with the look of one who says, “What fools some of these mortals be.”

’S a funny world.

Do you suppose Indians as exceedingly dead as the Bonitans could have ghosts still rambling around?