In King Tut’s Shadow

What was it like to discover an ancient Egyptian tomb?

If the breathless records from the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries are to be believed, it was an experience almost too marvelous to be grasped. Having cleared a portal back through the centuries, the dirt-caked explorer stepped through it, and there, amid the coded relics, found himself face-to-face with an eerily recognizable predecessor from distant antiquity—a mute figure, surprising in its completeness, long dead and yet in the immediacy and strangeness of the encounter, somehow very much alive.

Tunneling into ancient tombs was laborious—they had been designed to foil grave robbers, after all, and the intervening millennia had filled them with rocky debris. Arrival in the burial chamber was often disorienting. In the poor light, explorers momentarily mistook exquisitely mummified domestic animals for live ones. They found stacks of hard goods in the sarcophagi, but also dried flowers and the leavings of a last meal, as though only a few weeks or months had passed since the long-distant funerary rites. Arthur Weigall, an Egyptologist of the period who wrote eloquently about such moments, compared them to walking through a tear in the curtain of time.

Even more striking, almost magical, was the quickness with which that curtain repaired itself. Upon discovery, items in the tombs started visibly to decay. The sudden change in temperature and atmosphere made vivid colors fade and carved outlines all but disappear. A scholar assigned to copy hieroglyphs inside King Tut’s tomb when it was discovered in 1922 records that he worked to the sound of ancient wood creaking and snapping as the new air flowed in.

Of course, many items of immeasurable scholarly, artistic, and commercial value did emerge from these once-sacred spaces, and in good condition. That value has made them the objects of all sorts of disputes and passions, and there’s no shortage of either in the story of Theodore Davis, the American tycoon who played a central role in the development of Egyptology.

For more than a decade, beginning with his uncovering of the resting place of Yuya and Thuyu—parents of the glamorous Queen Tiye—in 1905, Davis was the world’s best-known opener of tombs. He made the Valley of the Kings his personal sandlot, uncovering eighteen sarcophagi between 1902 and 1914 and paying for the clearing of a dozen more. He was assumed to have exhausted the valley by the time he died, in 1915. But then Howard Carter and George Herbert, Earl of Carnarvon, unearthed the perfectly intact resting place of King Tut, the likes of which the world had never seen before.

In a single stroke, Davis and his legacy were all but buried.

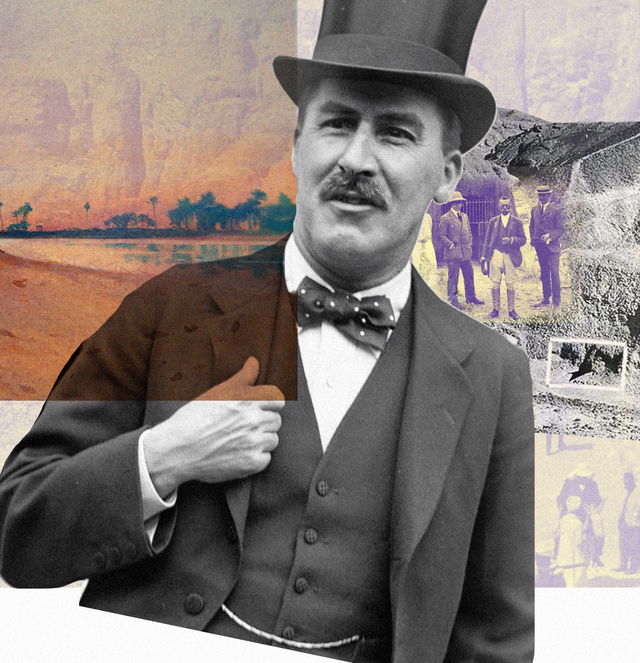

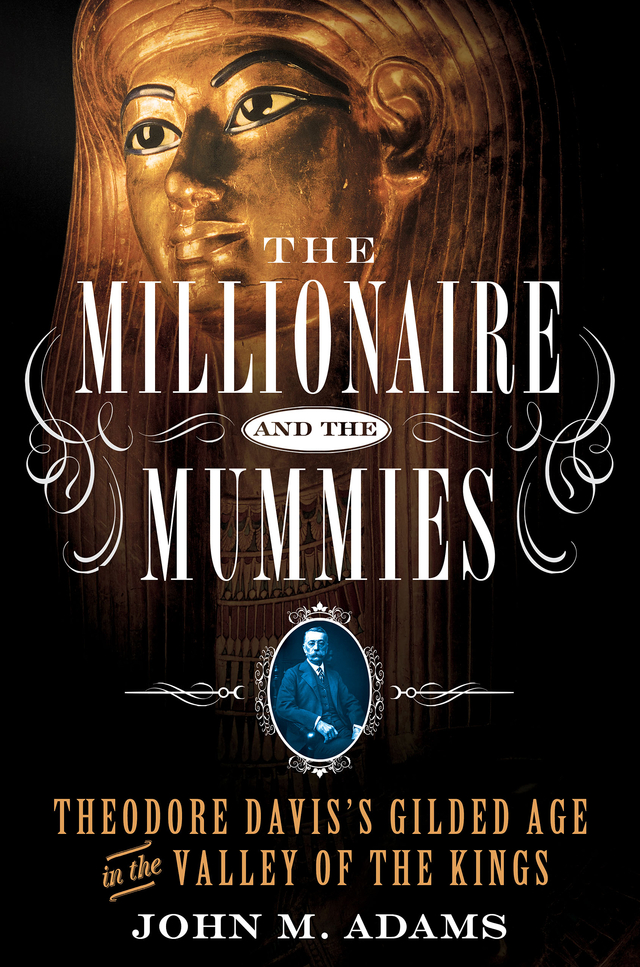

John M. Adams tries to exhume both in his new biography of Davis, The Millionaire and the Mummies. His is an approving portrait overall; given his subject’s reputation as a vulgarian and pushy egotist, it might thus be considered revisionist. The Davis who emerges here is brusque, virile, bent on advancement and self-improvement—in short, an archetypal alpha male of the Gilded Age.

Adams seems aware of his subject’s limitations. “He was not a particularly reflective man,” he writes, “and if spiritual or philosophical matters did not concern him much it was because the world had rewarded the pragmatic, materialistic traits his youth and young manhood had developed.” What, then, did Davis feel during those enviable through-the-curtain encounters? We learn that while contemplating Thuyu’s tomb he exclaimed, “Oh my god!” and promptly fainted. Beyond that, Adams offers precious little.

More interesting than Davis himself, perhaps, is the underlying story of how a self-educated opportunist from the American provinces became worldly enough to develop an enthusiasm for unearthing ancient tombs along the Nile. The book also sheds light on a pivotal moment in archaeology, at least in Egypt, when the culling of ancient ruins went from flat-out plundering to something resembling disinterested scholarship.

Davis was instrumental in the change. There’s some irony here, given that he made his fortune the way many did in the Gilded Age: by lying and bribing more effectively than his rivals. Born in 1838 in Springfield, New York, Davis grew up in Detroit, which was then still a frontier town. He worked as a lawyer in Iowa, then in post-Civil War New York City; he lived very comfortably, but it wasn’t until he started digging in the American Wilds that he became a millionaire.

Employing shady methods, to say the least, Davis formed a syndicate that invested in undeveloped territory around Lake Superior. He and his east-coast partners cut canals that opened up swathes of Michigan’s Upper Peninsula, putting small armies of men to work felling trees and sucking layers of muck out of swamps. “The canal builders operated five huge steam dredges, had laid track for the two locomotives and dump cars that removed the digging debris, used pile drivers to secure the sides of the canal,” Adams notes. “Nitroglycerin was used to blast apart the hardpan clay at the bottom.” These were rougher techniques than the ones Davis would later employ in Egypt.

The canals opened the Upper Peninsula to mining, which had of course been the plan all along. By 1872, the area was the source of 70 percent of all copper coming out of the United States. Davis made a killing by leasing land to mining companies here and elsewhere, and his profits allowed him to go into comfortable semiretirement in Newport, Rhode Island by middle age.

Around this time, he started wintering in Europe. Like many nouveaux riches of the day—and of many another time and place—he decided that his ticket to sophistication lay in collecting art. Davis, who was self-educated, attacked the hobby with his usual brute enthusiasm. “If you see any very fine picture which can be bought very cheap, please advise me,” he wrote to his art consultant, the Renaissance historian Bernard Berenson.

Davis started enjoyed art-buying a little less after acquiring a Da Vinci for a song, only to have it revealed to be a fake.

By the 1890s, The Land of the Nile (which was occupied by Britain throughout his time there) had become Davis’s new obsession. Having toiled for years in a nation that was energetically on the rise, he enjoyed lingering in one that wasn’t. “All countries seem youthful in comparison with Egypt,” he rhapsodized. Also, here he could prise precious objects from the ground himself, with little doubt as to their authenticity.

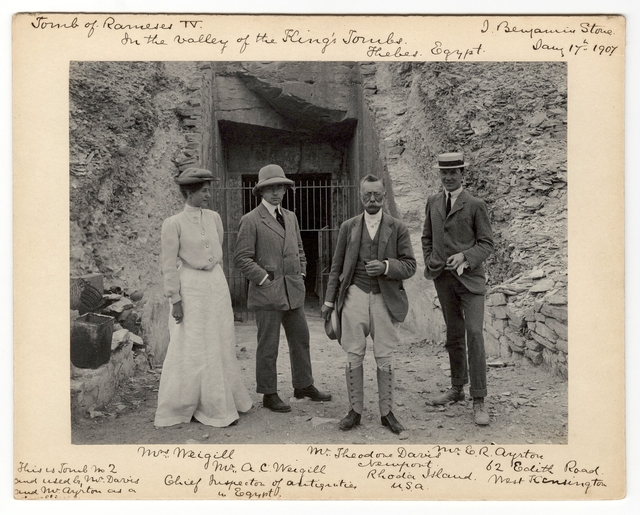

He didn’t literally discover these treasures himself, of course. Davis, who was in his sixties by the time he commissioned his first dig, spent much of his time in Egypt cruising up and down the Nile in his boat, the Beduin, with his longtime companion and mistress, Emma Andrews. He tended to visit excavation sites only when the archaeologist he’d hired or partnered with had something new to show him.

Theodore Davis alongside Mr. and Mrs. Weigall and E. R. Ayrton at the Valley of the Kings, 1907. John M. Adams, The Millionaire and the Mummies

The actual digging was done by local workmen, or fellahin, who were hired and supervised (and routinely extorted) by an Egyptian reis, or foreman, who in turn reported to the European archaeologist in charge. The toilers burrowed into hillsides and the desert floor, smashing through boulders with pickaxes and carrying tons of rocky debris out in baskets. In the Valley of the Kings, Daniel Meyerson’s colorful chronicle of the discovery of Tut’s tomb, describes the job in vivid terms:

By day, the labor was backbreaking, painstaking, grueling: There was the endless digging and sifting, often yielding nothing but a handful of dust; the crawling and clambering through suffocating underground passages filled with thousands of bats, centuries of their waste creating a poisonous atmosphere; the unstable shale under the solid limestone threatening to collapse. Death or crippling accidents were an ever-present danger.

Davis, aboard the Beduin, kept a leisurely distance from these discomforts. “We are happy on this wonderful Nile, with its warm, certain and hospitable sun and mild sweet airs,” he wrote. But if such an approach seems indulgently disengaged, it compares favorably to that taken by Lord Carnarvon in his early excavating years. The so-called “Carnarvon Tablet” hails from this era, when his lordship insisted on handling ancient relics himself, and the damage he wreaked on this important historical document has caused Egyptologists no small amount of anguish.

Adams argues that compared to other wealthy foreigners running digs, Davis did things responsibly. If he was impatient to make progress, he was also ruthlessly methodical, committing funding for years on end in a time when many patrons invested in dig sites the way they might bet at the racetrack.

Whereas his penny-pinching contemporaries relied on guesswork, Davis used his vast resources to hack the Valley of the Kings systematically down to bedrock—the archaeological equivalent of strip-mining. Davis wrote, not a little bit disingenuously, that he considered it “a satisfaction to know the entire valley, even if it yielded nothing.” It was almost as though, in an age of progress, it was not only passé but unmanly to be making tentative stabs at the earth.

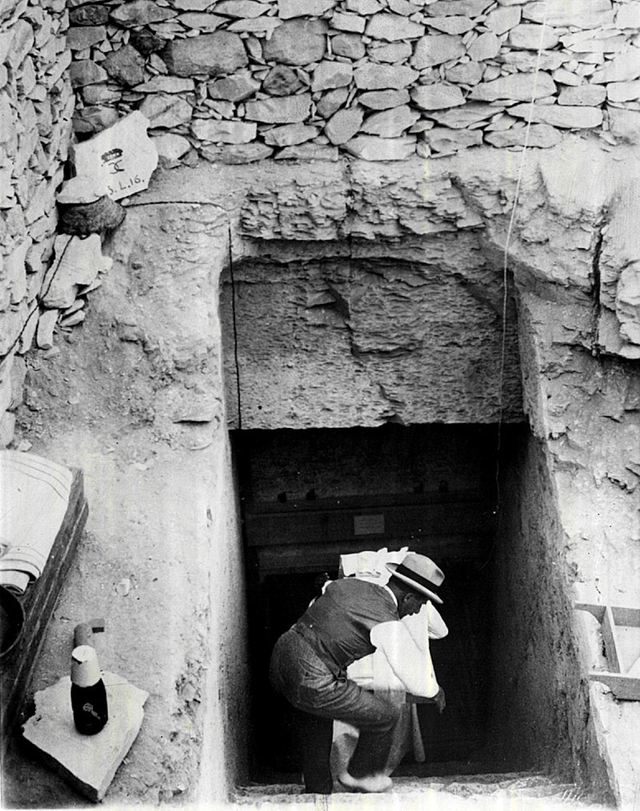

With his purposeful, scaled-up approach, you might say Davis Americanized the excavation process—all the more remarkable, then, that he ultimately lost out to Carnarvon, an English playboy who once quipped, “I would rather discover a royal tomb than win the Derby!”

Impressively, given his advancing age, Davis did slither and crab-walk into tombs once they’d been cleared; he even insisted on going first. He’d slogged through the Midwestern wilderness as a young man, and he was no claustrophobe. One imagines him relishing the opportunity to prove his fitness. For Davis, the Egyptian excursions provided more than one form of enrichment. Rudyard Kipling’s definition of archaeology comes to mind: “A scholarly pursuit with all the excitement of a gold prospector’s life.”

The Egyptomania that gripped America around the time Davis started digging—a time, it may be worth noting, that preceded Hollywood—revolved around glamorous royals. And so, embedded in all those headline-grabbing tales of Davis’s discoveries was an image—a validating one, to say the least— of an elite representative of contemporary America meeting the leader of the civilization that had built the Pyramids.

Davis’s one-time employee, Howard Carter, helps empty King Tut’s tomb in 1923, all but burying Davis’s legacy. Wikimedia Commons

Davis was in thrall to these ancient royals, but often cavalier once he’d found them. Thinking (incorrectly, it turned out) he’d discovered the tomb of Queen Tiye he obnoxiously described her in an interview as “a very beautiful and attractive lady whom I am sorry I did not have the opportunity of meeting.”

Davis brought careless entourages into tombs, unfortunately a common practice at the time. Mummies were pawed at, and crumbled; priceless items were handed out like party favors. Adams relates the story of the French Empress Eugénie, the widow of Napoleon III, who, feeling fatigued after her descent into a tomb, helped herself to a 3,500-year-old chair. (Miraculously, it did not break.)

Unlike Carnarvon and others, Davis was not contractually entitled to a share of the spoils. The Antiquities Service, however, let him keep many treasures that he unearthed as “gifts.” (It is thus likely that Egyptian nationalists of the time would have viewed him as just another foreign pillager. Adams does not go into this, or discuss how Davis fits into the cultural-heritage disputes raging today.) Many of these precious keepsakes Davis gave away, hoping to impress friends. The skull of a Ramesside prince became a paperweight on his desk in Newport. And he donated liberally, when he felt like it, to the Boston Museum of Fine Arts and to the Metropolitan. “Davis made the point,” Adams writes, “that immortal masterpieces should be shared with the entire world—just as soon as he was done with them.”

From a reader’s distance, Davis seems easy to pigeonhole. Yet he also experienced something that mere museum-goers and even today’s meticulous professionals can only guess at: the feeling of stepping into the dark, blind, with no idea—be it from cameras, sonar, or any other modern spoiler alert—of what may lie inside. Such rarified moments might have set his soul alight.

Or he may have been reveling in something more banal. As Adams puts it, “Davis was a rogue, a criminal who found that great wealth did not bring personal fulfillment, and like other robber barons of the Gilded Age he tried to fill his soul with fine art and romance.” Unlike the others, he didn’t look up, but down.