Trade Tales and Tiny Trails: Glass Beads in the Kalahari Desert

The archaeological site of Khubu la Dintša in Botswana is littered with broken-down entranceways of mud and stone melted and slumped inwards on themselves: dirty, stacked lumpy piles defeated and retired from the seasonal rains. Paths lined with stones taken from those archaeological walls have been kicked out of alignment by grazing cattle or scampering kudus. Less than ten years earlier, large stone circles led to a dancing floor in front of a collapsing wooden structure, which housed purification basins. Thirty meters beyond these basins, at the base of a man-made cave christened by a sacrificed snake, sits a clay-lined basin, still filled with blue-and-white striped glass beads. Although these beads are modern, they have ancient echoes that extend nearly 1,000 years ago in the past.

Glass beads, more than any other type of artifact, help us make sense of the last 600 years of Kalahari history. Even today, they play a role in local Batswana communities and public health and medical treatment; and as such, glass beads are woven into the social fabric of Khubu la Dintša, just as they were when Indo-Arabian traders introduced them to Africa. Glass beads help link the archaeologist to a time and a place beyond ancient texts and oral histories, when this part of Africa—thousands of miles from the Indian Ocean—traded with the Middle East, India, Indonesia, and China. This is a story about the tiny trails of history the beads have left us. In the past as well as in the present, these beads have played a social role in how people connect themselves to one another and their ancestors.

I first held these glass beads in 2009, as a graduate student working on these prehistoric, pre-European African cities and kingdoms. Looking at these tiny artifacts, I struggled to control my breathing, terrified of blowing them out of my hand back into the Kalahari dirt. These colorful glass seed beads, many of which can hardly fit in the edge of a pin, traveled a long, long way to get to the Kalahari. During the Southern African Iron Age (~600-1750 CE), these tiny beads traveled as commodities around the Indian Ocean, passing through the hands of many traders and sailors from the Middle East and Asia to eventually arrive at in Botswana at Khubu la Dintša.

Basin containing blue and blue-and-white striped glass beads offered as part of the phekolo ceremony that took place at Khubu la Dintša from the mid-1990s to the early 2000s. Carla Klehm, 2010

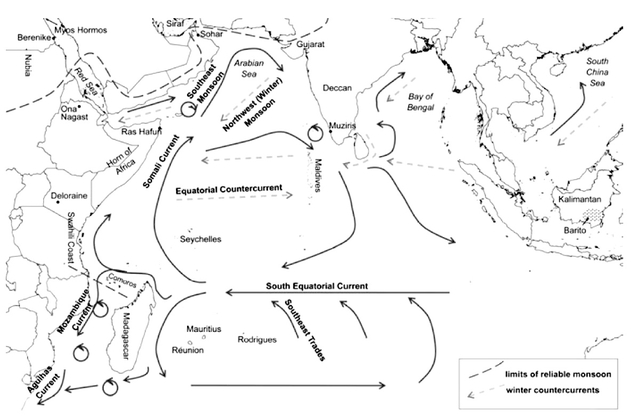

From about 600 to 1750 CE, the Indian Ocean trade played a crucial role in the development of cities and kingdoms in southern Africa. Communities that grew sorghum and millet on landscapes filled with wandering goats, bleating sheep, and herds of cows began to become involved in regional and long-distance exchange that ultimately linked them to Indo-Asian trade systems that used the monsoon winds to trade among Africa, the Middle East, India, China, Madagascar, and Indonesia. In southern Africa, trade involved goods including ivory, gold, rhino horns, exotic animals, and more locally iron, copper, tin, salt, and cattle. These goods were traded for cloth, prestige ceramics, and, of course, glass beads.

Our site of Khubu la Dintša (in the 13th and 14th centuries CE) differed greatly from its contemporaries, both in and out of Africa. In 1415 CE the ancient city of Malindi was visited by a Chinese ambassador sailing a fleet 250 times the size of the Columbus voyage, and gifted the Chinese emperor Yong’le with two giraffes. In the 15th century CE, just a few hundred kilometers east of Khubu la Dintša, Great Zimbabwe controlled the southern African gold trade, and was guarded by free-standing stone enclosures up to 36 feet high and 20 feet thick, built with cut granite blocks without the use of mortar. Khubu la Dintša did not have Chinese visitors nor did it have architectural feats in stone. Yet, the Khubu la Dintša people and their glass beads were linked to all of these players—a node in the network of trade goods and ideas.

Map of the Indian Ocean monsoon wind and ocean currents that connects East and Southern Africa, the Middle East, and South and Southeast Asia. Nicole Boivin, Alison Crowther, Richard Helm, and Dorian Q. Fuller, “East Africa and Madagascar in the Indian Ocean World,” Journal of World Prehistory 26(2013): 221

Arab, Chinese, and Portuguese documents describe the lands where they are trading for gold, but geographic locations are often lacking, leaving most of the continent a virtual question mark in terms of where and how settlements and cities developed. Written documents by Arab, Chinese, and Portuguese traders describe their travels, but anything outside of their mercantile focus leaves unmapped and unknown areas. These trade networks extended thousands of kilometers into the interior of Africa—far beyond the explorations of these travelers—and we are left with archaeological evidence to infer their expanse. The glass beads, however, can fill in these geographic gaps. The analysis of the excavated beads’ chemical composition, through mass spectrometry, allows us to retrace these trade routes to deep into the interior of Africa. Major and minor elements in these glass beads can be used to be diagnostic of the place of origin (provenience) as well as the technological advances in melting the glass, making the beads, and coloring them. From this, we’re able to infer a best estimate of when the beads were manufactured. Ancient glass is most often made from silica sand, to which an alkali or alkali earth-based flux is added to keep the melting point low. The glass beads found in sub-Saharan Africa are made from three main components: silica (from the sand), lime, and soda (the alkali). The type of soda can be broadly diagnostic of when and where the glass beads were made. With Indian Ocean beads, it’s either mineral soda or plant ash soda glass. Magnesium oxide (MgO) serves as the simplest determinant of the soda type: plant ash beads contain more than mineral soda glass beads, often substantially so.

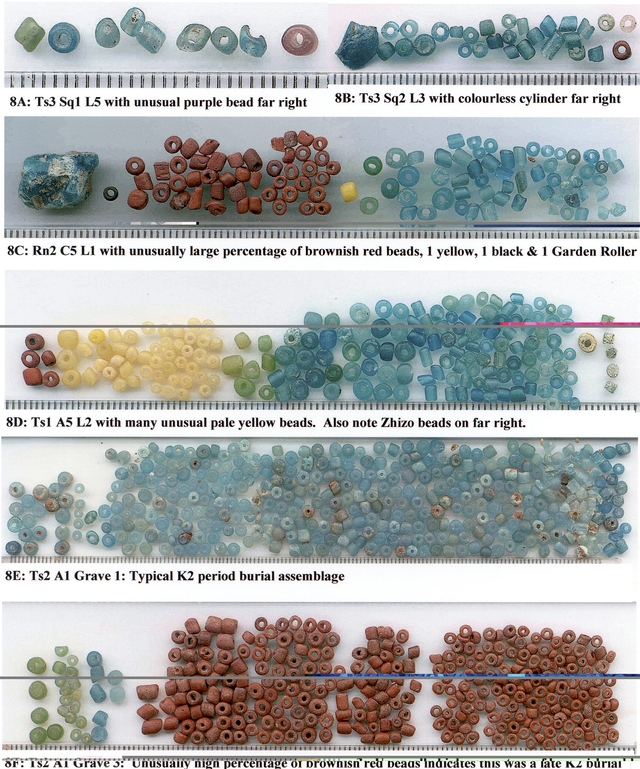

We now know that many of these early glass beads that come to the Kalahari date to the 8th century CE and come from the Middle East—from Iran and areas east of the Euphrates River. These beads are followed by high aluminum mineral soda beads during the 10th century, from South or even Southeast Asia. By the 13th century—and what we see at Khubu la Dintša—are mostly high-aluminum, low-lime (CaO) glass beads that again are coming from the Middle East, from an area distinctly (read: chemically) different from earlier. By the early 15th century, the beads are again flowing from South Asia, and are documented by Portuguese sources that help trace their places of origin. The beads and their material history fill in where the other documents leave off.

Khubu la Dintša is actually a small site—one of a number of similar sites—clustered around the ancient trade center, Bosutswe. For hundreds of years, Bosutswe (700-1700 CE) was a major regional hub for Indian Ocean trade. Bosutswe functioned as both a trade bottleneck to gain access across the Kalahari up towards the Congolese Basin and as a provider of cattle—a crucial component for those long journeys undertaken by traders. The cattle trade at Bosutswe peaked between 1200-1450 CE, when the highest number of “status” items like glass beads and bronze metal jewelry are found at the site.

Khubu la Dintša, dating from 1220-1420 CE, is located 14km to the northwest of Bosutswe. Both Bosutswe and Khubu la Dintša are hilltops, and just close enough to one another that one can see smoke, fires, and signals from one hilltop to the other. At Khubu la Dintša, two long, 30-meter stone walls border the site. In between the walls, scraggly patches of buffalo grass (Cenchrus ciliaris), signify the location of ancient remains; this vegetation preferentially grows on the thick kraal (animal pen) deposits that are characteristic of African Iron Age sites, outgrowing almost every other type of vegetation. These kraals would have been where the animals were kept at night after long days of grazing the nearby grasses.

Ancient stone walls associated with the site of Khubu la Dintša, dating back to the 14th century CE. Carla Klehm, 2010

My own recent excavations at Khubu la Dintša revealed a surprising find: 229 Indian Ocean glass beads. The concentrations of these glass beads from Khubu la Dintša were higher than the elite areas at Bosutswe, the elite trade center. Not only could these sites see one another, they were also intimately connected. These beads, and local and long-distance trade brought these two sites together, linking them economically, with Bosutswe the major center and therefore its political ally. These sites were linked socially as well, as other artifacts like elite ceramics suggest that alliances between the settlements at both sites were political allies through marriage.

One strong possibility for these tight ties may be that Bosutswe depended on Khubu la Dintša for access to grazing grounds that an outlying site like Khubu la Dintša would have been able to control. As Bosutswe became increasingly important in the regional trade, the increased number of cattle would have needed good grass and plenty of areas to graze in. Moreover, increased riches associated with this long-distance trade would have meant more cattle for the elite at Bosutswe—a major status symbol in ancient southern African societies. The marginal environment of the Kalahari Desert would have meant that outlying communities would have been incorporated both economically, but also through social and political alliances and ties, possibly through marriages. Khubu la Dintša would have been a place to keep the cattle, bought with their burgeoning riches, and an opportunity for the site to get rich on glass beads.

While trade at Bosutswe Khubu la Dintša was beginning to die out in the 15th and 16th centuries CE, trade elsewhere in Africa was still thriving along with the introduction of a new trade player: the Portuguese. It is through the diaries, notes, and records associated with these Portuguese merchants and, later, British colonials, that we continue to trace the story of these ancient glass beads, and the many people they encountered.

View of the Bosutswe region from the top of Khubu la Dintša. Bosutswe is the hilltop located in the far left area of the landscape; Mmadipudi Hill, another Iron Age hilltop site, is visible on the far right. Carla Klehm, 2011

Portuguese merchants became involved in this Indian Ocean trade in the 15th century CE and quickly noted the high trade value placed on glass beads. And their African trade partners were specific about their point of origin: only glass beads originating from the Indian Ocean were considered proper currency. European glass beads were considered unacceptable. Therefore, Portuguese traders would travel all the way to ports in India in order to obtain beads for African trade. George McCall Theal, a British historian at the turn of the 20th century, translated many of these Portuguese documents. In a few short samples, these Indian Ocean glass beads appear repeatedly:

1513: The merchants take to Sofala gold which they give to the Moors without weighing for coloured cloths and beads which among them are much valued, which beads come from Cambaya.

1554: Among them was one of whom the rest seemed to make the most account … he was distinguished from them by wearing a few beads red in colour, round, and about the same size as coriander seeds, which we rejoiced to see, it seeming to us that these beads being in his possession proved that we were near some river frequented by trading vessels, for they are only made in the kingdom of Cambaya, and are brought by the hands of our people to this coast.

1554: As the purpose of that king in desiring to have us there was not all founded in virtue, but partly in interest, a plague which generally infects most people (however rustic they may be), his hope was to get some gold or jewels by it, not because such things were necessary for his use, but because he knew that the Portuguese of the ship which came there in the past years bought these things from those who robbed Manuel de Sousa Sepulveda, giving beads in exchange, which they consider as great a treasure as are gold and jewellery with us.

These Portuguese traders describe how glass beads played a large role in the exchange of African trade goods, especially gold. Noted in multiple accounts was the port of Cambay (present day Khambat) in southwest India, one of several centers for glass bead manufacturing. In the second passage, glass beads signal social standing in African groups in contact with Indian Ocean traders. Notably, the most distinguished individual wore a string of Indian Ocean glass beads. The final excerpt compares glass beads to other “valuable” items in the eyes of the Portuguese traders. The African traders saw little intrinsic worth in gold or jewels taken from a shipwrecked Portuguese vessel. These salvaged goods were seen as a way to trade for glass beads from the next group of Portuguese traders they would encounter.

Indian Ocean glass beads from the site of K2, a major Iron Age site in South Africa dating to the 11th century CE. These beads have been traced back to their Indian Ocean roots through LA-ICP-MS analysis. Marilee Wood, “Glass Beads and Pre-European Trade in the Shashe-Limpopo Region” (PhD diss., University of Witwatersrand, 2005)

Glass beads continued to remain important in southern Africa, even after the Indian Ocean trade had diminished. Dubroc cites an account from the famed David Livingstone, a 19th-century British missionary in Botswana, who interpreted glass beads as a form of monetary currency. He also noted that the size and shape of beads had different values, which he describes through pictures:

The Waiyau prefer exceedingly small beads, the size of mustard-seed, and of various colors, but they must be opaque … but by far the most valuable of all is a small white oblong bead…one pound weight of these beads buy a tusk of ivory, at the south end of Tanganyika, so big that a strong man could not carry it more than two hours.

Other colonialists in Africa took advantage of the perceived value of glass beads, bribing children to attend missionary schools. Even in the African Diaspora, while African peoples were traded as slaves to plantations in North America, South America, and the Caribbean, beads associated with the Indian Ocean trade retained importance. Newton Cemetery, located in southern Barbados, is a slave burial ground from the late 17th and early 18th centuries that contains first and second generation African and Afro-Caribbean slaves. In this cemetery, we see beads, including glass beads, play a significant role in the burial practices. For example, one burial (termed Burial 72, a male), was found with burial items which included European glass beads, drilled dog teeth, fish vertebrae, seven cowry shells, and a Carnelian bead from Cambay. Although Carnelian beads are stone, not glass, their Indian Ocean origins imply the enduring symbolic presence Indian Ocean trade had in African societies.

Burial goods associated with Burial 72 in the Newton Cemetery, Barbados. J. S. Handler, “From Cambay in India to Barbados in the Caribbean: Two Unique Beads from Newton Plantation Slave Cemetery,” African Diaspora Archaeology Newsletter, March 2007

We know glass beads traveled long distances—tens of thousands of miles—to get to their place in southern Africa 700 years ago. We know that these beads can retrace these routes, and tell us about a changing landscape of power for a people increasingly connected to the world around them—worlds overseas unlike anything that had ever been seen before. Their importance lived on long after this trading world was over, from the schoolyards of 19th-century missionaries, echoing in slave burials in the New World. However glamorous and glitzy these beads appear as artifacts, they still have a living cultural history—a voice and materiality that reverberates through Khubu la Dintsa even today.

From 1994 until the mid 2000s Khubu la Dintša was used as an ancestral church called Tumelo mo Badimong (“faith in ancestral spirits”). By 2002, Khubu la Dintša was a site for a yearly purification ritual, known as phekolo, headed by a local spiritual leader, Motofela Molato, every July.

Phekolo churches have sprung up informally around Botswana, partially in response to the outbreak and rapid spread of HIV/AIDS. Notions of AIDS as a punishment given from the ancestors, as witchcraft, or even boswagadi (the end result of having sex with the spouse of a dead person before a purification ritual) existed as alternative explanations for the endemic. Churches like Molato’s attempted to reconnect their members with their ancestors and sought a spiritual harmony with botho, or humanhood.

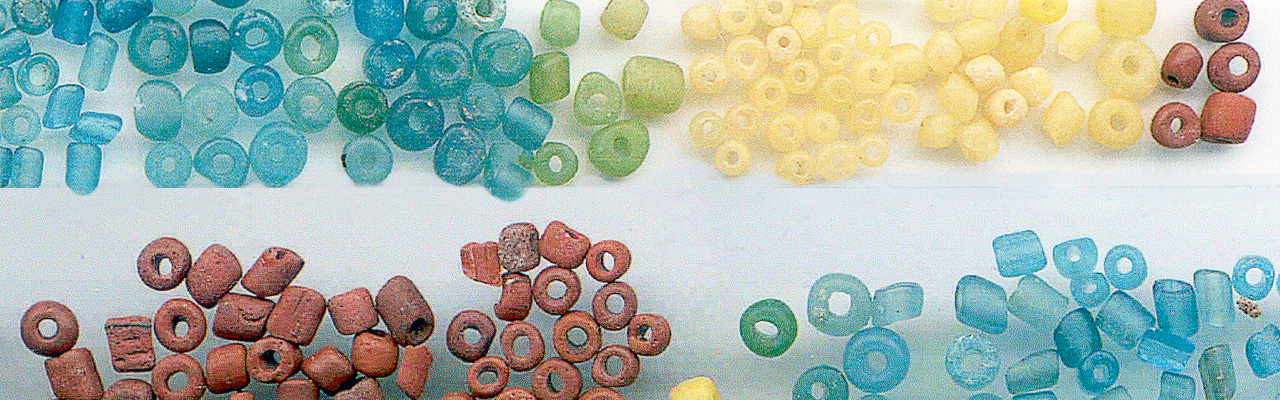

Blue-green, yellow, and brownish-red Indian Ocean glass beads found at Khubu la Dintša. Also visible in the photo are ostrich eggshell and other shell beads found at the site. Photo taken by the author in 2011. Carla Klehm, 2011

At Khubu la Dintša, spiritual imbalance brought 150 congregants together every July, traveling from the town of Letlhakane, over 160 kilometers away, to this place. At Khubu la Dintša, Molato saw lion paw-prints in some of the rocks on the hill. Lions have strong religious and symbolic importance in Batswana society, as they play part of a creation myth. Impressions in two of the rocks were thought to be lions’ footprints from a time when the earth was still soft. Small altars were built around each. Whitewashed stones, bleached as such to show association with the ancestors, lined the hilltop path to the main ceremony area. This main area included a dancing floor, lined with white ash obtained from archaeological deposits (ancient cow dung makes for white ash), to again make a connection to the ancestors. Cleansing basins located in a wooden structure allowed purification for the church’s followers. And, on the far side of the hill, glass beads were left in an offering for the ancestors, as a way to communicate, honor, and ask for help.

Today, only glass beads are left for us to infer the different cultural narratives that surround them. As objects of material culture, these beads help us go beyond the limits of ancient texts and explore thousands of kilometers into the African interior, linking the Kalahari to the Middle East and India over a thousand years ago. Beads boldly proclaim the emergence of another trade partner, Bosutswe, into the Indian Ocean trade network, and the complex set of relationships with outlying areas needed to keep the cattle coming. A shoeless congregation brought glass beads to this same place on cool, dark July nights. Beads that puzzle and draw curiosity of far-off worlds; beads integral to the making of self, that help people cling to a past and identity from the other side of the world into the afterlife; beads that speak to peoples coping with uncertainty in the world, with AIDS and spiritual imbalance, with frustration, anger, and hope; beads the archaeologist is left to decode, to listen to, to sort through their multiple stories.

The author would like to acknowledge and thank the National Science Foundation (NSF #1115148), National Museum of Botswana, the University of Texas at Austin, the University of Botswana, and James Denbow for supporting this part of her dissertation research at Khubu la Dintša, and Lydia Pyne and Christopher Heaney for their editorial help.