Mining the Languages of Empire in the Early Americas

In Potosí, the mining capital of the early modern world, smelted metals became entangled with the mingled identities of Spanish America. Benjamin Breen, 2013

“Oye hueón está tan rica la mina,” one operative said to his friend on a typical March day in the altiplano, nearly ten years ago.

It was warm in the sunny spaces where they walked, and chilly on the bench where I sat in the shade of the dining hall, waiting for a bus to take me up the hill and back to the classroom where I taught English to miners, metallurgists, and managers in my first “real job” after college. As one of a handful of women then working among some 700 male employees of Cerro Colorado, an open-pit copper mine in the north of Chile, I was used to catcalls and comments. But this one was different, because this miner used the technical language of his profession to say something prohibited by company policy. Mines, ores, and metallic grades are evaluated in terms of their richness (rica), and mina is slang for “woman,” at least in Chile. Thus, the miner said two things at once: “that mine has excellent metallic ore” and “that woman is so fine.”

Later, it struck me that the language of science, especially in applied, commercialized sciences like mining and metallurgy, might be full of these sorts of expressions of gender and sexuality—and probably race, ethnicity, and all of the nuances of human cultures, because people would translate the terms of their everyday lives into a language that revealed their particular ways of being in the world. So I went to graduate school and began digging in colonial archives for scientific texts that both revealed these kinds of terms and showed how metaphors came to matter in the seventeenth century.

The colonial period—with its multiple, uneven, and incomplete transitions from indigenous empires like the Inca and Mexica to the Hispanic empire—produced highly original expressions of mining and metallurgical theories and practices. New linguistic communities from Africa, Europe, and the Americas were thrown together, willingly and unwillingly, and they developed new technologies that required new terminologies.

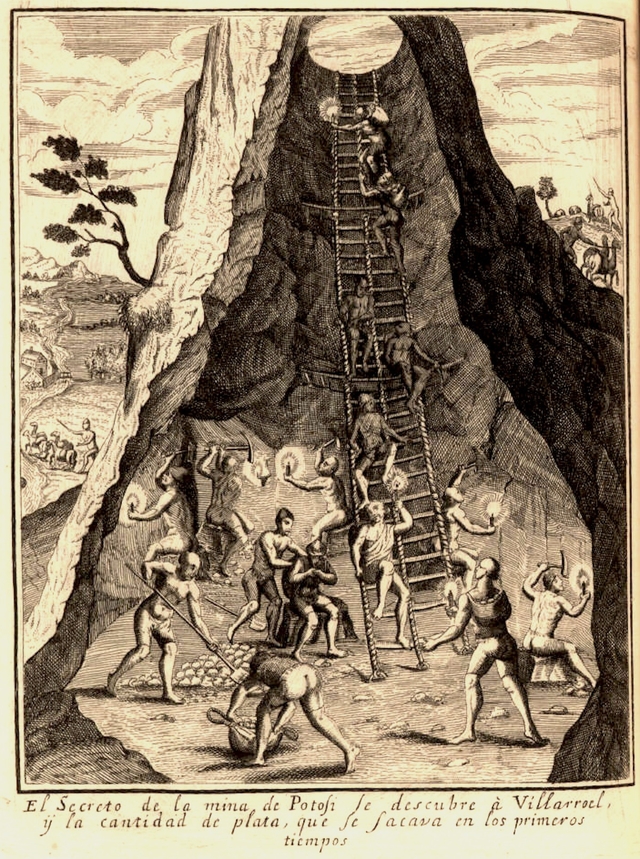

Nowhere do we see these patterns more clearly than in the silver industry, the largest sector of the Spanish American economy and one that generated some 86 million kilos of silver between 1492 and 1810. Because of its economic importance, the viceroyalties of Mexico and Peru were reorganized to facilitate the mining and minting of silver. This was the standardized currency of an empire that transported American silver to Asian markets in exchange for goods and peoples bought and sold in Europe and Africa. We have long known that the silver industry influenced life in the colonial Americas and the Atlantic world on social, political, and economic levels. Studying the language of silver mining shows how it shaped scientific ideas and even social categories.

Image of Potosí from Antonio de Herrera y Tordesillas, Historia general (Antwerp: Juan Bautista Verdussen, 1728). John Carter Brown Library at Brown University

The new method of amalgamation (nuevo beneficio de azogue) that developed in the highlands of central Mexico was crucial to the production of colonial silver and imperial wealth. Refiners in Renaissance Europe, like their predecessors in antiquity, had treated precious metals with mercury to recover particles from metals that were discarded into slag heaps. This was a very different procedure than the methods required to process ore that was excavated from the veins of deep, underground tunnels, and to treat varieties of silver (Ag) that were often mixed with other substances, such as lead (Pb), tin (Sn), or copper (Cu), which revealed different colors that miners skillfully identified on the walls of dark and dusty passages.

In Spanish America, mixed minerals were given names that indexed the multilingual nature of colonial mining and metallurgy with the racialized terms of colonial science. Silver bodies mixed with iron (Fe) and sulfur (S) were called metales mulatos y negrillos, and they were organized into what miners like Álvaro Alonso Barba called castas de metales. This scientific language and method of sorting helped to reinforce the classification practices that were employed by legal theorists and colonial officials to categorize mixed-race peoples (castas) into hierarchies based on socioeconomic status, kinship networks, and skin color.

In mining, as in the legal negotiations of casta status for indigenous, black, and creole subjects, these categories of silver were determined in relation to one another. As one metallurgist instructed his son, some metales mulatos (mulato metals) had to be smelted like negrillos, while others were amalgamated with mercury, following the methods used for pacos—a Hispanized version of the Quechua term ppaqu, or “reddish.” In his Directorio de beneficiadores, Juan de Alcalá y Hamurrio analogized metallic mixtures to children who took equally from their mothers and fathers to explain why metales mulatos “are a middle point between pacos and negrillos, formed of both natures.”

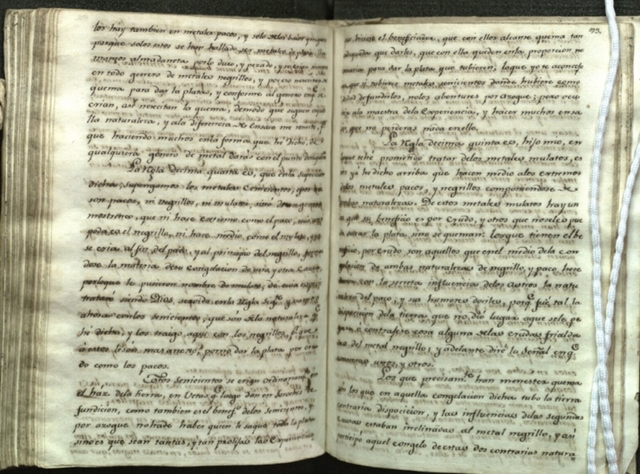

Juan de Alcalá y Hamurrio, Directorio de beneficiadores (1737 [ca. 1691]: Lima [Potosí?]), 90. Center for Southwest Research, University of New Mexico.

But Spanish was not the only language providing the terms of classification in colonial silver mining and metallurgy. Indigenous artisans figured so prominently in the mining of silver and its refinement into imperial wealth that officials in Alto Perú required native plateros (silversmiths) to practice within the city limits of the Villa Imperial, rather than provincial smitheries, and they punished non-compliers with two years of service in the Hospital de los Naturales (Indian Hospital). Given the demographic dominance and technical masteries of indigenous miners and refiners, it is not surprising to find that Spanish miners accommodated the sounds and syntaxes of the Andean languages Quechua and Aymara.

In and around Potosí, for example, surface-level mixtures of silver and copper were called pacos, “reddish,” while gray-blue mixtures of silver and lead were called oques, or what one Spanish metallurgist translated as “friarish” suggesting that indigenous miners analogized the gray robes of Franciscan friars to the metals that they harvested from mines. One scholar has traced the use of oque-colored threads in quipus to specific kinship networks, called ayllus, suggesting that we might be able to use the linguistic footprints of these naming practices to determine the identities of native mining communities in ways that written documents alone have not allowed.

Historians of the colonial Andes have long suggested that indigenous and Iberian metallurgical methods were two separate systems, and that the one, in which native miners used wind ovens (guairas) to process high-grade ores, declined throughout the seventeenth century, as the other, marked by new technologies that amalgamated low-grade ores like negrillos, rose over the course of the colonial era. The language of silver amalgamation treatises, however, allows us to see where and how indigenous knowledge systems and technical practices shaped the science of colonial silver, just as native names for minerals—and their Hispanized forms—provided terms of classification.

But first, we need to have a sense of what the ten-step process of colonial amalgamation looked like. According to Modesto Bargalló, minerals were crushed (1) and sorted into piles (2), at which point they were watered, mixed with reagents, namely mercury, salt, and a solution of distilled copper, called magistral (3-5). The wet mixtures were then stomped (6) and washed (7) to separate the incorporated mercury from the silver (8). The unincorporated mercury was removed from the bins to be used again (9), while the incorporated masses were sent to refining ovens (10), some of which were specially designed to separate mixtures of silver and copper or lead.

We now explain these changes with chemical formulas that show how mercury brings out silver particles by binding to other elements:

Cu2Cl2 + 2Ag2S + Hg > 4Ag + 2CuS + Hg2Cl2

Early modern miners and refiners, however, had to use other terms in the days before the development of modern chemistry. Unsurprisingly, they applied terms and ideas they already knew to explain the physical and chemical changes in this new process, much as we use computer analogies to explain the inner workings of the mind (“my hard drive is full”) or car analogies to explain obtuse political processes (“Congressional debates are stuck in reverse”). And, also unsurprisingly, the old terms didn’t quite fit the new realities.

European metallurgists described metals in the humoral language of antiquity. Following natural philosophers and medical writers like Empedocles (ca. 495-435 BCE), Galen (129-200), and Aristotle (384-322), metals, like people, plants, and planets, were classified as hot, cold, wet, and dry, in various combinations. Silver (Ag) and lead (Pb), shared what Vanoccio Biringuccio (1480 – ca. 1540), smelter and munitions manager for Pope Paul III, called in his Pirotechnica a “unione amichevole” marked by “simpasta con l’altra.” This friendly union was so named for the sympathy (“simpasta”) or similarity that the two metals shared, and these ideas informed deep patterns of analogical thinking in which natural scientists explained botanical growth, tidal patterns, and the movement of stars across the sky in terms of human emotions like love and sympathy, or else enmity and antipathy.

Silver (Ag) and chemically-related quicksilver, or mercury (Hg), were also friendly substances, so their coming together involved, as Biringuccio explained in emotionally neutral language, “tak[ing] from the substance that the material contains.” This metallic union of similar things—like all combinations of like bodies—did not produce anything new or cause matter to change shape, humoral theory suggested, because only opposite forces like hot and cold, or male and female, could do so.

Refiners in the colonial Americas also used the terms of natural philosophers like Aristotle, but they did so in different ways. For metallurgical writers like Álvaro Alonso Barba (1569-1662) in Peru and the physician Juan de Cárdenas (1563-1609) in Mexico, the friendly similarities of silver and mercury transformed during the amalgamation process into a relationship marked by desire, appetite, embrace, and penetration—the kind of productive and reproductive terms typically reserved for the generative couplings of different essences.

In his Problemas y secretos maravillosos de las Indias (México, 1591), Cárdenas argued that sympathy and likeness made it possible for silver and mercury to incorporate in an erotic act of embrace (abrazar):

mercury, through the aforementioned friendship, embraces silver; one must understand that silver and mercury love and appeal to each other, procuring through their friendship to embrace and unite, the one with the other; they are cast together and the mercury incorporates the silver so as to embrace it through its great friendship and analogy, because it is such a friend and so familiar with the silver.

Barba made the same conclusion in Peru, insisting with the full weight of thirty years of experience as a metallurgist in the Andes that the “friendship” of the two mineral bodies allowed them to generate new amalgams, called pella:

The closeness and convenience that mercury has naturally with metals is clearly shown, absent other arguments, by the ease with which it unites with metals, penetrates them and becomes imbued, converting them into what we call pella; it keeps no such company with any other thing.

The metallurgical technologies developed in Latin America required that colonial practitioners reinterpret the traditional definitions of similarity and difference, scientific concepts and analogical roots that had been transmitted from antiquity to the medieval Middle East and Renaissance Europe. These new ways of thinking made possible the unimaginable wealth of the Hapsburg Empire in the early modern era, along with material and economic realities that were impossible to ignore. By tracing the shifts in language that colonial scientific writers like Barba and Cárdenas used to explain New World technologies, we can appreciate how a new understanding of what it meant to be like and unlike allowed indigenous African and Iberian miners to scale up metallurgical methods from the Old World, and to use them to treat new mineralogical mixtures in new ways.

But language alone cannot explain why or how these scientific practitioners came to their new ideas. For that, we need to compare what miners said in their own words and how their letters were translated for other readers. Vocabularies and ideas that circulated in Renaissance Europe were translated comfortably enough from one European language to another. English translators easily found Aristotelian terms like “sympathy” and “antipathy” to express relationships between American metals, even when they and their readers had never seen or heard of these ores before. But when translators get the terms wrong, we can see where they struggle to find ways to express ideas and practices that are new to them.

In 1670, Edward Montagu (1625-1672), Earl of Sandwich and English ambassador to Spain, published his translation of Barba’s Arte de los metales, revealing ideas that were translated and mistranslated across imperial scientific discourse. For example, Barba recommended that miners incorporate mercury to partially-formed amalgams in two steps, resulting in higher yields of silver and fewer material losses: “y mientras mas fuere menos conchos se causarán.” However, Montagu translated the passage as “the more Quicksilver there was, the fewer inequalities like Oyster shells will be produced,” taking the term conchos to mean “Oyster shells” because he did not realize that Barba used a Hispanized version of the Quechua word qunchu (dreg, sediment, remains). We have already seen how Quechua terms for varieties of silver were incorporated into Spanish names for raw materials, but this passage allows us to see where indigenous vocabularies structured the practices of new metallurgical technologies.

This moment of mistranslation might also help to explain the conceptual origins of the new definitions of similarity and difference that large-scale colonial amalgamation technologies required. Whereas Spanish writers used a language of emotion and affect (abrazar, amar), Montagu described the union of silver and mercury in much more neutral terms: “for the Quicksilver to lay hold of, and incorporate itself with the Silver that is in it,” “so shall the dry Plate be collected together.” Like the case of conchos/dregs/“Oyster shells,” the mistranslation of abrazar/embrace/“lay hold” shows where Montagu misses the mark, perhaps because the new understanding of the generative potential of similarity emerged in whole or in part from indigenous or creole knowledge systems in the Americas, rather than the epistemologies of the Old World with which he was familiar.

Historians have long recognized the unique demographic conditions of colonial American mining and metallurgy, and they have noted that it cannot be a coincidence that new technologies of amalgamation were developed in these spaces. Silver mining was by far the largest industry in Spanish America, one whose impact on global markets, transportation networks, and economic exchanges throughout the Hapsburg imperial world was, according to Peter J. Bakewell “almost beyond measure.”

Fortunately, new interdisciplinary methods emerging in the interstices of history, literature, linguistics, and archaeology are allowing us to study the contributions of indigenous and creole miners and refiners in ways that more traditional approaches have not always allowed. We might never be able to measure the full impact of miners who “wrote without letters,” as Walter Mignolo has so wonderfully put it. Yet integrating literary methods of close reading with histories of science allows us to catch a glimpse of these women and men who shaped the making of a new world in the early modern era.

By digging into old archives in new ways—taking texts in their original languages to root out the epistemological play of discourse and mine the coloniality of power—we can begin to see mining and metallurgy not just as material cultures, but also as cultures that matter.