International Diplomacy (and Chocolate) in the Archives

I began my Fulbright year in Lucca the day before my birthday. Feeling a little lonely, I decided to walk around the city and get to know the place. As I walked down Via Santa Croce toward Piazza San Michele, I saw that people were lining the fronts of their businesses and homes with tiny candles. When the sun finally set, the city sparkled with thousands of flickering lights. The façade of San Michele lit up with candles and torches of its own and shone its light on the crowd that had gathered in the piazza for the procession of the Holy Cross. That night, I shared the centuries-old tradition of Lucca’s Luminaria with tourists and townsfolk alike.

Lucca is a medium-sized city between Florence and Pisa. These days, it is generally known for its centro storico and distinctive Renaissance walls, which have since been converted into a park and recently celebrated their five hundredth anniversary. Lucca is also the focus of my current research, which relies on a collection of documents in the Archivio Storico Diocesano, the episcopal archive of the city. In 2005, I won a pre-doctoral Fulbright fellowship, which gave me a year in which to explore collections, develop my dissertation, and learn the strange and mysterious art of digging for undiscovered treasure in historical archives.

In a way, I made an earth-shaking discovery before I even entered the archives. Over the weekend, I had received a call from my advisor asking if I had seen the headlines; there was a story about Lucca that I should see. Turning the corner to the newsstand, the headline struck me immediately: “Lucca, Monsignor Arrested for Receiving Stolen Goods.” The night of the Luminaria was also the night authorities arrested Monsignor Giuseppe Ghilarducci, director of the episcopal archive of Lucca and priest of several local parishes, for receiving sacred objects stolen from museums and churches in Rome, Viterbo, Terni, Naples, and other Italian cities. The article listed altar cloths, vestments, kneelers, chalices, and a small marble altar among the hundreds of stolen works of art discovered in the episcopal palace of Lucca and churches in Mons. Ghilarducci’s parishes of Vetriano, Colognora Pescaia and Celle di Puccini. I had planned on starting my research the next day, but now I wondered about my letter of permission from Mons. Ghilarducci. I was already in over my head, and I had been in Lucca for less than a week.

The following day, I entered the episcopal archive and introduced myself. The archivist, a small, middle-aged, and impeccably dressed woman, greeted me with a harried expression that was understandable under the circumstances, and introduced me to Mons. Ghilarducci. I had read in the newspaper that he had been placed under house arrest, but I had failed to grasp that his “house” was the episcopal palace, which contained the episcopal archive.

Autumn trees growing atop the ancient and remarkably preserved city walls of Lucca. Jscarreiro/Wikimedia Commons

Over the next few weeks, I learned the skill of making small talk in a foreign language while ignoring the only topic of interest in Lucca. I also learned, to my relief, that Mons. Ghilarducci was not some villainous cleric from a Dan Brown novel. While I cannot excuse anyone’s ownership of stolen artifacts, he insisted to the authorities and the press that he had bought the items in good faith. It was hard to condemn this earnest and soft-spoken seventy-year-old priest, and soon the charges surrounding Mons. Ghilarducci ceased to define him. Out of curiosity, I looked up his work only to find that he was responsible for a number of articles and an edited collection of eleventh-century manuscripts from the episcopal archive. He asked about my work and suggested collections that might be helpful, and I grew to see him as a real person and a fellow scholar.

More than once I wondered if this was the kind of diplomatic endeavor Senator Fulbright had in mind.

In 1945 U.S. Senator James William Fulbright of Arkansas proposed a bill to use the proceeds from sales of U.S. war surplus to fund international exchange. On August 1, 1946, President Truman signed the bill into law, effectively creating what would later become the largest educational exchange program in history. The Fulbright program now operates in over 150 countries worldwide and has aided over 120,000 U.S. and 200,000 foreign scholars since its inception. It is overseen by the U.S. State Department’s Bureau of Educational and Cultural Affairs (ECA), which still largely bills the Fulbright program as a diplomatic effort. I am sure the ECA conceives of this effort primarily as exchange between scholars in international settings, but there is something to be said for the exercise of international diplomacy in the small world of regional archives.

The Archivio Storico Diocesano di Lucca as it appeared in Pierre Mortier’s 1640 map of Lucca and today.

The Archivio Storico Diocesano di Lucca does not easily let visitors forget its history or its owner. It resides in the episcopal palace in Via Arcivescovado, just across from the Duomo di San Martino. The cathedral, begun in 1063 by Bishop Anselm—later Pope Alexander II—and given a gothic overhaul in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, casts an imposing afternoon shadow over the Palazzo Arcivescovile. The palace itself is the result of a fourteenth-century foundation with expansions in the fifteenth and eighteenth centuries, accessible through a grand fifteenth-century wooden door by Jacopo da Villa. The palace and adjacent archive might blend into the surrounding structures if it were not for a prominent arcade on the balcony of the piano nobile. It is impossible to walk between cathedral and palace without having some sense of the grandeur of Lucca’s medieval and Renaissance past.

After entering through da Villa’s portal, a courteous, if officious, administrative assistant directs scholars to a cramped, antique elevator. On the second floor, the interior of the archive only reinforces the impression of history. After leaving their bags in lockers in the hall, scholars can walk, blissfully unencumbered, into the archive’s reading room. A beautiful electric chandelier and the daylight that comes streaming in from the high windows along one wall light this room. The walls are covered in a rich, dark red that compliments the long wooden tables that serve as desks. Bookshelves full of inventories line the walls and frame the archivists’ desk at the front of the room. Despite the efficiency of its administration, this is no sterile, modern library.

In this room, I learned one of my most valuable lessons as a scholar: befriend the archivists. A scholar in any archive—especially a smaller regional one like an episcopal archive—is more or less at the mercy of the archivists. They have access to the manuscripts, and no one is a better source of information on inventories or uncatalogued collections that might be helpful. They are also human beings, which can be frightening when you realize how much power they have over the successful completion of your research.

In this respect, chocolate can become an invaluable research tool.

I discovered this handy fact one day when I requested the next volume in a series I had been reading. The archivist shook her head sadly and told me that it was impossible. I asked why, imagining that perhaps it was under seal of confession, catastrophically damaged, or lost. I was surprised then when she said she could not bring it to me because it was on too high a shelf. I asked if I could come with her to help, and she kindly led me up to the attic. Yes, the attic.

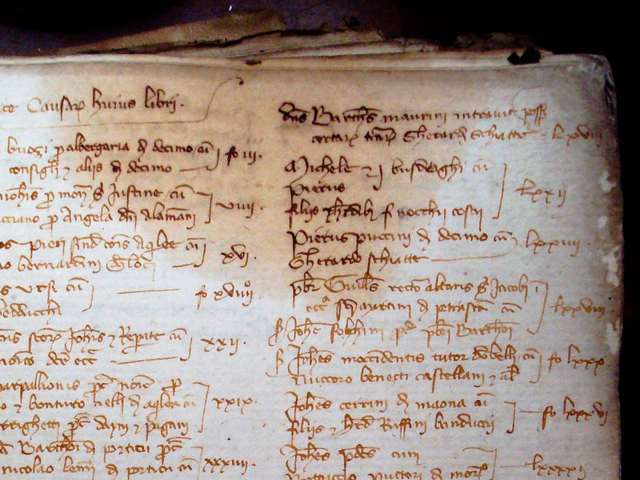

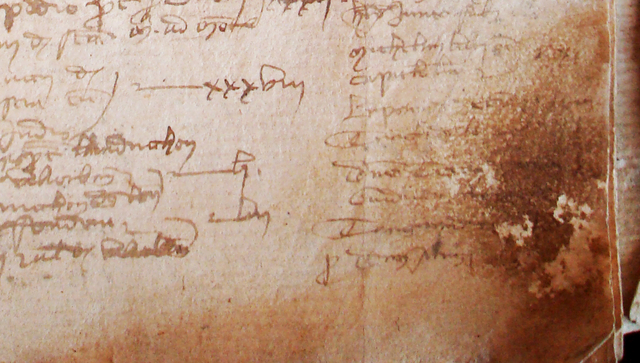

As I climbed up the stepladder to reach the volumes I needed, I could not help but wonder about the effects of a centuries-old attic space on the huge stacks of parchment and paper on the shelves. I soon learned that a leak had already done its work. The roof had, of course, since been repaired, but not before it had damaged several late medieval codices on the top shelves.

Between an archivist who could not reach the top shelf and the damage wrought by a leak, I realized suddenly what a particularly human endeavor it is to work in an archive like this one. Since the episcopal scribes first produced them in the 1340s, the codices I was reading had been handed down from one set of keepers to the next. All of them have had to contend with threats ranging from wars and natural disasters to bookworms and leaky roofs.

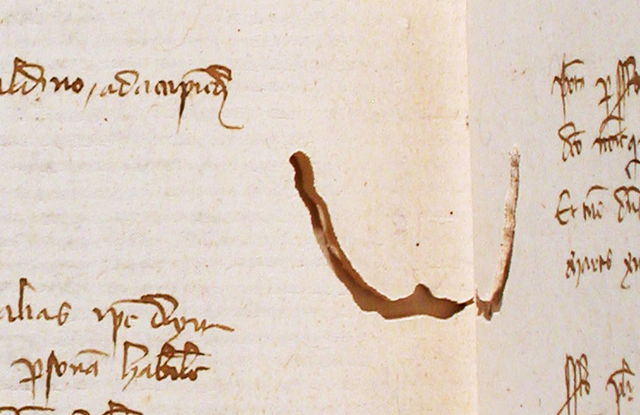

Folio corner damaged by skin oils. Archivio Storico Diocseano di Lucca, photo by Corinne Wieben Lampert

Every scholar who consults these records and every individual and scribe whose stories and efforts they preserve owe thanks to this unbroken line of custodians. I thanked mine with chocolate.

No scholar produces in a vacuum. Our acknowledgment pages are filled with thanks for our mentors, our colleagues, our fellow researchers, our students, our benefactors, and, often, the priceless archival staff who helped us through those first difficult days digging through a new collection. Describing the purpose of the Fulbright program in 1983, Sen. Fulbright said that international scholarly exchange “can turn nations into people, contributing as no other form of communication can to the humanizing of international relations.” Sure, bringing a box of chocolates to the archivist who let me into the attic may not be exactly what Sen. Fulbright had in mind when he envisioned a grand program of diplomatic and scholarly exchange, but he did grasp how real diplomacy works. It is easy for us to think about the practice of international exchange as an act performed by nations rather than individuals, but individuals give faces and voices to their nations. These experiences transformed the episcopal archive from a faceless institution to a group of dedicated scholars who shared my love of the past and my desire to preserve it.

When I returned to the archive in 2007 the archivists teased, “Dove sono i nostri cioccolatini?” Where are our chocolates?

I promised that next time I would come properly equipped for archival research.