Following a Migrant Route

I still don’t know where I’ll be staying tonight. But I’ve accomplished the few tasks I needed to get done by this evening. I have a rental car that is neither fancy nor colorful. I have taken my husband’s advice and found a dusty road on which to drive for a handful of miles, so that the car stands out even less for what it is—full of a graduate student’s arsenal of technology. And I have arrived at my first stop, Brawley, California, before sunset. For the next month, I’ll be driving from this southernmost site north to Yuba City.

In the two to three days I have allotted for each stop, my goal is to find and visit (wherever possible) the sites of each of the thirteen migratory labor camps built in California by the Farm Security Administration in the late 1930s. These camps were modest and rural—designed to meet the immediate need of thousands of migrants, many having driven to California from the Dust Bowl states, seeking work and sanitary shelter. Residents stayed in each camp only as long as they could find work in the vicinity. Thus, the camps were located at intervals up California’s central agricultural corridor. In all but one case, I do not know what I will find remaining on-site. Given that the camps were initially built as temporary communities, I hold little hope of finding much in the way of physical, let alone architectural, remains. Yet I have convinced myself that it is important to know whether any parts of these sites still stand, even if I find only plowed fields where there were once communities of government relief and mutual aid.

Driving through the largely abandoned downtown of Brawley, wondering where I will stay for the night, I feel ill-prepared. Yet I have intentionally put myself in this situation. Although I have a rough schedule for the upcoming weeks, I haven’t made any reservations in advance. My plan is to build flexibility into the schedule, to let myself overstay if a particular site or archive is especially rich, and to pass through quickly if I find nothing but subdivisions and closed libraries.

It occurs to me only later that some of my anxieties about this trip—deeply unfamiliar mobility, worry over carrying so many valuables in the trunk of my car, uncertainty whether I will find any work worth keeping me at each stop along the way—echo those of the people whose migration I am researching.

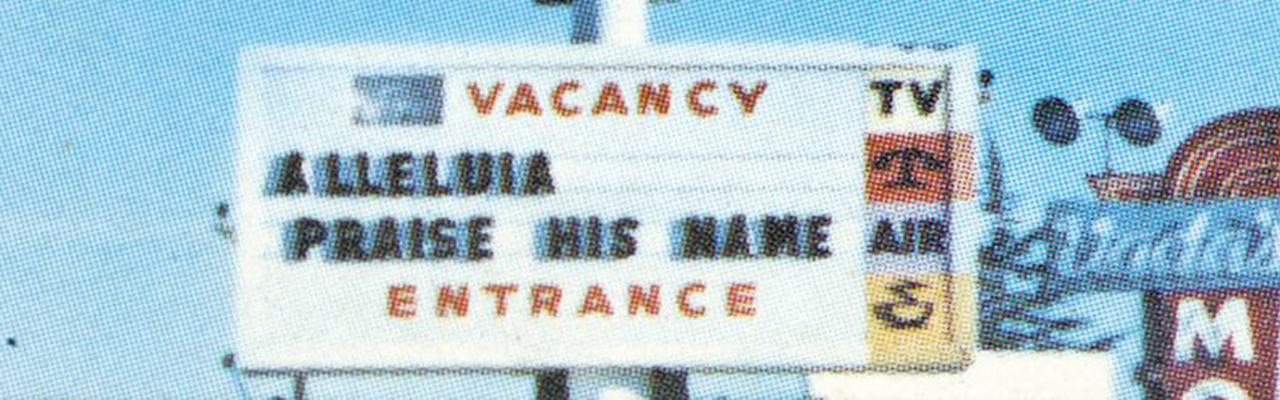

Having budgeted $45 a night for lodging, my choices in Brawley are few. I find a vacancy in a motel near the Salton Sea, check into a second-floor room, bring my equipment and a change of clothes in from the car, and set into inhaling my fish tacos. At first the cable TV drowns out the noises from the neighboring room. Soon the sounds get louder, the screams more audible. The wall I am leaning up against shakes. I turn off the TV. A woman’s voice is the only consistent noise, interrupted periodically by crashes, vibrations. What do I do? What does she need? Before I can decide which number to dial on the phone, heavy footsteps pass my door, a fist pounds on the adjacent one, and the screams stop. I turn the TV back on. That night I sleep fitfully.

First thing the next morning I re-evaluate my budget. No more taquería lunches or dinners will buy me another $10 a night. My hotel choices expand considerably.

In many of the counties I plan to visit, I have a general sense of where the migrant camps had been located. But here in Brawley, and neighboring Indio, I know only that there was a camp somewhere in, or immediately outside of, town. On the hunt for maps or plats that may identify a precise location, I begin at the Planning Department. They send me to the City Clerk’s office. The City Clerk suggests perhaps the Planning Department or the Chamber of Commerce. The Chamber of Commerce has a locked vault with historic materials, but no key.

At the Brawley Public Library I ask to see copies of the Brawley News published between 1935 and 1940. Large, hard-bound volumes emerge—one for each year. Placing them carefully on my table, the head librarian asks after my project. I explain that I am trying to locate the site of the FSA migrant labor camp that was built somewhere in Brawley. She shakes her head emphatically: “There were no internment camps in the Imperial Valley.” This is neither the first nor the final time that I will shake my head in response, and insist to the helpful archivist (to myself as well?) that the camps I seek are quite different in kind than those she is imagining. At a time when Californians were fighting vigorously to prevent any programs that would enable migrants to stay in their communities—fearful that they brought with them diseases both social and biological—these camps were designed to re-assert the respectability of their migrant residents. Bathing and laundry facilities provided bodily cleanliness, while a system of self-governance entrusted the residents with the organization and care for their communities. I am aware that my optimism about these camps is at odds with some historians’ perspectives. Yet the more stories I read about them, the more I find an instructive example of intelligent and productive government aid.

In the years of newspapers that I scan that afternoon, I find two specific references to the location of the Brawley camp. One article locates it at the W. I. Wilson tract just north of city limits. Another refers to its location on Imperial Avenue just north of town. On the way home I drive north on Imperial and find subdivisions on both sides of the road. Eventually Imperial dead-ends into a construction site for what appears to be another housing tract. I take pictures aimlessly.

My last hope in Brawley is the Pioneer’s Museum, which is affiliated with the Imperial County Historical Society. The Museum is ten miles south of town. I call before making the drive. Carol, who answers the phone, is quick to clarify she is only the gift shop attendant: “My only exposure to that era is reading Grapes of Wrath.” I tell her how apt her association is, that in fact John Steinbeck worked closely with the camp manager at the Arvin camp, and interviewed many of the residents, when researching the novel. She promises to ask Mike, their historian, if they have any maps in their collections. Two hours later my phone rings. “You’re in luck! We have a historic map of all the labor camps in Imperial County on display.” I am elated, and leave immediately.

My car is only the second in the lot. As I enter, Carol calls from the far corner, “You must be Josi,” and tells me Mike will be down in a few minutes. Browsing the display of local taxidermy—some quite lifelike and others uncannily stretched—I wait with guarded optimism. Mike leads me upstairs to the chronological exhibits of agriculture in the county. He excitedly points me past the nineteenth-century farm equipment to the “Hard Times” exhibit, and tells me the map is in the display case at the front of the diorama. I approach the scale-model of an Okie’s truck, piled high with miniature possessions. Adjacent to the truck is a framed print of Dorothea Lange’s “Migrant Mother.” I delight in the details of the diorama—the whimsical stuffed crows, the Highway 99 road sign—before turning my focus to the historic map.

The map inside this glass display case, shielded from air and curious hands, consists of a piece of paper approximately two feet wide, cut out in the shape of the state of California. Atop the map sit what look like red Monopoly houses. Coffee stirrers bridge the space between the little houses and their corresponding labels. The town names—“Brawley,” “Calipatria,”—are printed, cut-out, and neatly laid atop of the map, outside of California’s flattened outline. No suggestion of topography adds precision to this featureless outline; the scale of the plastic houses suggests the camps were the size of the cities that housed them. And no distinction has been made between squatters’ camps, private camps, and government camps; the list of sites seems to include whatever camps Dorothea Lange and fellow FSA photographers documented.

I ask myself what I had expected: a government published map, perhaps, or at least one that originated in Imperial County; the indication of streets or specific tracts of land; the label of “FSA migrant labor camp” somewhere along a street named Imperial? Although this map represents an inclusive, if unspecific, documentation of sites where migrants found shelter, it will not help me get any closer to locating the Brawley camp. I marvel for minutes, then move back downstairs. Mike is nowhere to be found. All I hear is the buzz of overhead fluorescent lights and the motor of Carol’s electric wheelchair, on which she is circling the first-floor exhibits. I slip quietly out the door.

My next destination is Kern County, where the Arvin and Shafter camps were established. Arvin, or “Weedpatch” as it is more commonly called, has long been the most famous of the FSA communities because of its association with John Steinbeck’s The Grapes of Wrath. I know for certain that a handful of historic buildings remain there. I head directly to the former camp site. My enthusiasm mounts as I pass the Weedpatch supermarket. Then I see the historic water tower in the distance. Familiar from so many FSA photographs of this camp and others, the water tower assures me that I am headed in the right direction.

The water tower at Arvin had stood at the center of the migrant labor camp, and today is my first view of what remains of Weedpatch. Josi Ward, 2013

Pulling into the parking lot at Arvin, I pass over a large speed bump and a “Children playing” sign. I recall that as they first pulled into the camp, the Joads’ “whole truck leaped into the air and crashed down again.” Cursing at the jolt, Tom asked the watchman what purpose it could possibly serve, and received the reply: “a lot of kids play in here. You tell folks to go slow and they’re liable to forget. But let ‘em hit that hump once and they don’t.” A common speed bump was the first signal for the Joads that this camp cared about the people, and children, living within.

Although I had known that some historic buildings remained at Arvin, I had not been prepared to find that the Arvin Migrant Center is still in operation, still housing migrant agricultural workers for roughly six months of every year. Although the site has moved from federal to state to county auspices, I discover it has served this purpose consistently since the days of the FSA program. The demographics of the workers have changed since the New Deal years, of course. Whereas the residents of the initial camps were primarily white Americans displaced from their tenant farms, now the workers are predominantly Mexican Americans who live further south most of the year—in Brawley and Calexico—but come up here for the months of the harvest. I cannot imagine that the federal government of today, nor even of 80 years ago, would have built such ambitious communities for an immigrant population. Yet it strikes me as an important legacy of the FSA program that these spaces now serve a population whose health and rights are of even less concern to the American public than had been those of their white predecessors.

Today the parking lot is empty; the season has not yet begun. Albeza at the front desk is patient with my curiosity, and offers to unlock the chain-link fence that surrounds the collection of historic buildings, abandoned but stable, in the far northeast corner of the site.

One of the two metal shelters still standing at Weedpatch. This shelter serves as a storage building today, while the other is empty and accessible to inquisitive visitors. Adjacent to the shelter stands the recently restored community center building. Josi Ward, 2013

Albeza leaves me be, and tells me I’m free to walk inside any of the buildings that are open. I am most excited to see two of the ubiquitous one-room, metal shelters still standing. These structures were considered an upgrade from the rudimentary tent platforms in the earliest camps, yet because they are such modest structures, I had suspected most would be gone. I have long wondered how families lived in these small spaces, how any furniture or belongings might have fit in addition to bodies. The shelter is empty, its concrete floor swept clean. I measure its dimensions: 12’ by 16’. Having wondered what the heat must have been like in an all-metal shelter intended for a desert, I am surprised how cool the air is. A breeze passes through the screened windows. I extend my arms and cannot reach the peak of the roof.

From the shelter I walk into the only other unlocked building. The community center is vast where the shelter was small. Yet like the shelter, this building is open within—a virtually undivided interior space. Traces of “Dust Bowl Day” are scattered throughout the room, remnants of what had been an annual festival in which former residents of this and other FSA camps met on site for a day of music, food, and memories. I try to imagine the noise of the events this community center has hosted; not just the recent festivals, but also the Thanksgiving dinners and sewing classes and elementary school plays I have read about in the documents of the camp manager, Tom Collins. The weekly reports that he submitted to the regional office of the FSA are exhaustive catalogs of arrivals and departures, and births and deaths. They contain detailed accounts of baseball games, marriage proposals, bible studies, and carpools to the fields that betray his pride in the camp as well as in the residents who planned and promoted these community events. As vivid as his stories were, and as inspired as I felt reading his tender accounts of life at Weedpatch—nothing shakes the sense of utter emptiness in this enormous hall. Today this room feels forgotten.

The undivided interior space of the Arvin community center is typical of these buildings at other FSA camps. This picture was taken from the raised stage at the rear of the building. Josi Ward, 2013

After the successful visit at Arvin, I have virtually no expectations for the visit to Shafter. Counting on such rich discoveries would surely lead to disappointment. Like the Arvin camp, Shafter still has an active Migrant Center on site. Also like the Arvin camp, it is virtually empty; only one family has arrived so far this season. This time I don’t notice any identifiably historic buildings; no familiar community center or metal shelter. When I ask the manager, Alfredo, if he recalls when the old buildings were torn down, he informs me several remain, and offers to drive me to them. (“It’s too hot to walk!”) I gratefully comply.

Alfredo is generous with his time and his stories, and seems amused as I take pictures of the oldest, most neglected structures on site. As we drive past the old bathhouses, I notice a metal shelter in the distance, surrounded by a chain-link fence. The profile of these shelters is becoming quite familiar. I ask if we can see that building too. Alfredo seems pleased. He tells me he had lived in a metal shelter at Arvin for a few years in the mid-1960s. I ask him what the heat was like. He groans. To cool them down, he explains, they would lay a carpet over the roof and soak it in water. But he also explains that the heat wasn’t such a problem because it was safer then, “You could sleep and live outside.”

I recall how active the community spaces looked in the historic photos I’ve found of these camps and remind myself to keep this explanation in mind. With shared bathhouses and community center buildings, the vast majority of private and public life must have happened outside of the houses. So it seems all the more significant that individual family shelters were provided, despite all other facilities being communal. It dawns on me that the transformation of house into home was yet another activity enabled by the camp program.

All but one of the metal shelters from the Shafter camp were removed years ago, auctioned off for use as storage sheds and outbuildings. Josi Ward, 2013

Alfredo lets me help to move the rubble, weeds, and debris from the front door of the shelter so that he can open it. He explains that the last of the metal shelters were removed in the 1980s, but points out the rows of concrete foundations that still remain. “Why did you keep this one?” I ask. “For history,” he smiles.

The weeks pass slowly as I move from Shafter to Woodville, Tulare, Firebaugh, Westley, Thornton, Winters, Yuba City, Gridley, and Marysville. If needed, I spend the first day locating the site. The next day is the visit, the interviews, the photographs. Finally, the public library, the local historical society, the microfilm reels. I become accustomed to finding agricultural labor housing on site, and to finding roads and community spaces laid out exactly as they were by the FSA planners. The ubiquitous speed bumps comfort me, as they once did the Joads. The wide porches and circular windows on the gable ends of the community centers become so familiar that I easily identify the buildings, even when significantly remodeled. I come to rely on the sight of the water towers—unused artifacts at the center of living landscapes—to guide my route to the camp sites.

This portion of a mural on the site of the former Linnell camp in Tulare represents the two most recognizable features of the FSA community—the community center and the water tower—both of which still stand at the center of Linnell Farm Labor Center. Josi Ward, 2013

The former community center at the Yuba City unit was converted into a school building in the 1960s, and today serves as a preschool for the Yuba City Unified School District. Several interior walls have been added to subdivide the interior space, but otherwise the floor plan remains largely unchanged. Josi Ward, 2013

The routines of mobility also become familiar. With each relocation, I feel less vulnerable. The nightly move of technology and a change of clothes from trunk into motel room, the morning purchase of block ice for the cooler, the 6pm call to assure my husband all is well; these things comfort me that I am safe and my work is progressing incrementally. The motel rooms remain inconsistent, but my routine becomes steadying.

By the time I return home to Ithaca I am satisfied that the trip was well worth both the expense and the anxiety. The purpose of these site visits was to encounter the history of these camps in ways that cannot happen at the archives. This month’s research has given me a sense of architectural scale and enclosure; it has introduced the voices and faces of people with memories of the camps; and it has prompted some empathy with the logistics and vulnerabilities of regular relocation.

I remain as far removed from the residents of these camps, their losses and fears and consolations, as I ever was. What I feel slightly closer to are the ways that this network of FSA camps—the series of communities designed to be occupied and left on a seasonal basis—served their temporary residents. As an architectural historian I was prepared to think about how facilities and spaces within the camps enabled certain routines, both communal and private. But until I followed the route myself, I hadn’t contemplated how meaningful routine itself must have been. As residents repeatedly relocated to follow the promise of work elsewhere, they found a few places that were both physically and socially familiar. Among the many provisions of these camps—the running water, the weekly dances, the committee meetings, the community gardens—the promise of familiarity for migrating families must have been invaluable. This discovery alone was worth the trip.