Losing Face

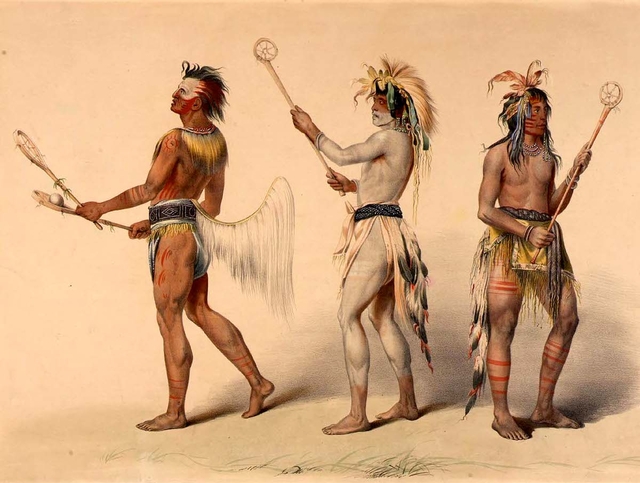

“The operations of my brush were entirely new and unaccountable,” Catlin wrote among the Sioux. Wikimedia Commons

This short piece focuses on “digs” as insults and their potentially tragic consequences. As has been well documented, Catlin traveled into the Sioux territory to paint Native Americans in the 1830s. While historians and anthropologists appreciate his colorful portraits for their historical and ethnographic value, we can also look his diary for ways that his presence could be a destabilizing one. Here, I paraphrase an encounter Catlin described between himself and two prominent Sioux men (and their families) that reveals the unexpected—and sometimes tragic consequences—that his “cross canvas” encounters could stimulate. You can read a full description of the event in his notes on the experience.

In 1832, aboard the steamship Yellow Stone, painter George Catlin ascended the Missouri River. His goal was to encounter, document, and deliver images of American Indians for education—and profit. His companions were an edgy lot: men looking for furs to buy and land to claim.

The party stopped at the principal trading post for the powerful Sioux Nation. Six hundred families made up the village. Some five to six thousand Indians waited to meet the government agent, but a smaller group, who Catlin decided to paint, was less patient.

“To these people,” Catlin recorded, “the operations of my brush were entirely new and unaccountable, and excited amongst them the greatest curiosity imaginable.”

Before him revered Indian leaders posed. All went well until a few unnamed medicine men warned that the portraits would cause “endless trouble.” The high-spirited leaders ignored their counsel and persevered, asking Catlin for the portraits they so desired.

But the leaders’ jocularity gave way to tension when the posing Mah-tó tchee-ga—or Little Bear—was offended by a jibe. Shón-ka, his rival who was also known as The Dog, declared that “Mah-tó tchee-ga is but half a man.”

Brief silence followed, then Mah-tó tchee-ga retorted. He demanded that Shón-ka justify his allegation. Shón-ka pointed to the artist’s canvas, where Catlin, bored with painting warriors head-on, had painted Mah-tó tchee-ga’s profile instead.

Mah-tó tchee-ga recounted his adversary’s failings in battle, and then, finishing the insult, derided Shón-ka as a “an old woman and a coward!” Shón-ka slunk off, shamed by communal laughter. Mah-tó tchee-ga, portrait complete, returned to his lodge to prepare for the anticipated altercation. But his wife, unfamiliar with the earlier encounter, had removed the bullets from his gun.

Pride wounded and animosity fueled—Shón-ka followed Mah-tó tchee-ga home, and challenged him to a duel. A bullet shattered the side of Mah-tó tchee-ga’s chin and blew his left cheek off his face. Shón-ka walked away.

Dying, Mah-tó tchee-ga lost face for the second time that day.

Catlin, blaming Mah-tó tchee-ga’s wife for the death, rode off to remember it his way.

The preceding account was paraphrased from George Catlin’s own sometimes-flowery Letters and Notes on the Manners, Customs, and Conditions of North American Indians, Vol. II, (First edition, 1844), Reprint, (Mineola, N.Y.: Dover Publications, 1973).