“And Raising His Hand He Gave the Finger to Heaven”: Digs and Disses Throughout History

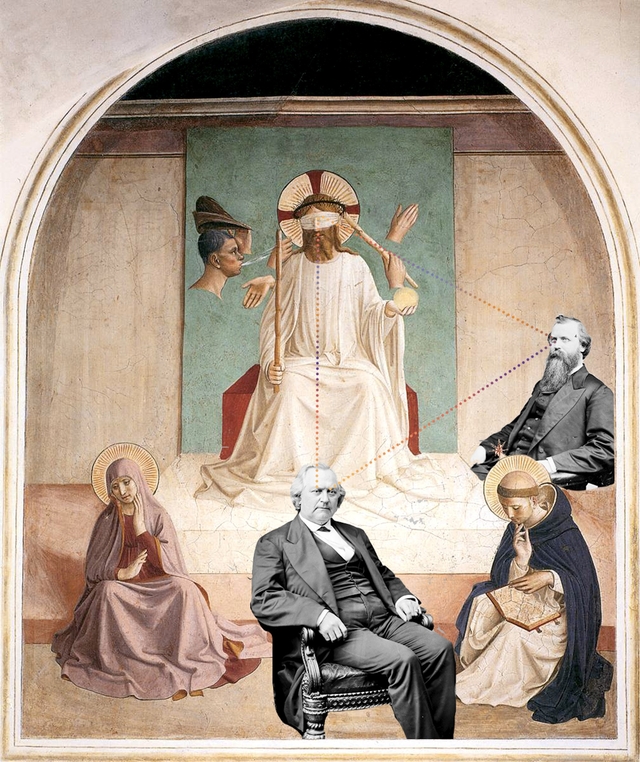

Fra Angelico, The Mockery of Christ, 1441 (with the addition of Senators Stewart and Nye). Wikimedia Commons

Senator William Morris Stewart was nothing if not a shrewd man. In 1850, he dropped out of Yale University and moved to California to become a gold miner. Like many savvy 49ers, Stewart soon realized that the real money and power lay in building an infrastructure to support the miners rather that digging in the dirt himself, and he became a lawyer specializing in the law of silver mining claims. He was wildly successful: attorney general of California by age twenty-six, and United States Senator for Nevada by thirty-seven.

It was at the Senate, in 1869, that he engaged in a sardonic exchange with two powerful Senators: Thomas Hendricks of Indiana and his fellow Nevadan James W. Nye (the latter had recently fired his young personal secretary, an up-and-coming writer named Samuel Clemens, for mailing prank letters to his constituents).

It’s impossible to tell from the surviving transcript of the 1869 debate, which involved railroad funding, whether Stewart was actually furious or just pretending to be for comic effect. Suffice to say, his two great loves appear to be hyperbole and defending the honor and business interests of the good folk of Nevada:

Mr. STEWART. I am glad that he has not made up his mind to annihilate the State of Nevada. The people out there will be exceedingly gratified when they learn the fact that the great Senator from Indiana does not intend to do that.

Mr HENDRICKS. Oh do not crush me with your wit.

Things went on like this for quite some time. Stewart accuses his Indiana enemy of “every abomination that was ever advocated in this body, by speaking of the number of people in Nevada.”

At this, the presumably witty Senator Nye jumps in:

Mr NYE. I hope my colleague will leave a little for me to do, for I want to take a dig at that. [Laughter.]

Is this the first recorded usage of the phrase “to take a dig at” someone, used as an insult? Or an ad-libbed witticism relating to the debate’s mining theme? Or both?

Hard to say, and etymology dictionaries are of surprisingly little help. One thing is for certain: authors, writers, politicians, and other makers of history have been taking digs at one another for a long, long time. Here’s a sampling of some of our favorites, emphasizing lesser-known insults from forgotten backways of the past. There’ll be no Winston Churchill calling people ugly here—but there will be Giordano Bruno giving Jesus Christ the finger from his jail cell in 1590s Venice. And isn’t that so much better?

[Fra Celestino] says that he deposes against Giordano, because he suspects that he has been slanderously denounced by the same, and informed against Giordano in writing. He reports that Giordano has said:

…

3) That Christ is a dog cuckold fucked dog; he said that the ruler of this world was a traitor, because he could not rule it well, and raising his hand he gave the finger to heaven.

…

11. That if he had to go back to being a Dominican friar, he wanted to blow up the monastery, and when he had done that, he wanted to return to Germany or England among the heretics where he could live in his own way more comfortably and plant his new and infinite heresies there.

12. The person who compiled the breviary is an ugly dog fucked cuckold, shameless, and the breviary is like an out-of-tune lute, and in it there are many things that are profane and irrelevant, and therefore it is not worth reading by serious men, but ought to be burned.

—Claims made to the Venetian Inquisition by the “mad Capuchin” Fra Celestino against Giordano Bruno, 1593, as translated by Ingrid D. Rowland in her excellent book Giordano Bruno: Philosopher/Heretic, pp. 245-46.

He lays in bed after the alarm goes off and rather than make my mouth filthy by asking him to get up I get up and get it myself. Also all the week he was loafing in camp milling chocolate all day long he never even offered to cook supper.

It is only for a little whole longer and by keeping his helper I can get along fine. His helper even is getting disgusted and the other day asked me if W. wasn’t afraid of wearing out his ass as he hasn’t even got off it for ten days.

—Ned Anderson complaining about his partner on the Yale Peru Expedition, October 15, 1914. Read more about this wonderfully mean-spirited letter in our article “One of the Damnedest Trampling Matches You Ever Saw”: When Archaeologists Talk Trash.

“If told I am a bad poet, I smile; but if told I am a poor scholar, I reach for my heaviest dictionary… The point is not that one version is better than the other (frankly, there is not much to choose between the two); the point is that unwittingly both use the same wrong person as if all paraphrasts were interconnected omphalically by an ectoplasmic band.”

—Vladimir Nabokov complaining about two rival translators missing the subtleties of an idiomatic use of the second person in a Lermontov poem in “Nabokov’s Reply,” Endeavour, February, 1966, pp. 80-89.

Contemporary hunter-gatherer life can tell us a great deal about the world of states and empires but it can tell us nothing at all about our prehistory. We have virtually no credible evidence about the world until yesterday and, until we do, the only defensible intellectual position is to shut up.

—James C. Scott reviewing Jared Diamond’s The World Until Yesterday (2013) in London Review of Books, Vol. 35, No. 22, November, 2013.

Finally, here’s a letter I found at the Virginia Historical Society in 2009. It had nothing to do with what I was researching at the time, but I was charmed by it and filed it away. The 1779 letter was signed “Downright Honest,” but attributed to a physician named Philip Turpin, mainly remembered today (if he is remembered at all) as a correspondent with Thomas Jefferson, who wrote to him about “traversing the air with balloons.”

Sir I must begin my letter to you with an apology for the liberty I take in writing to you on a disagreeable subject. Few People can bear to be told of their Faults, and for that reason often remain ignorant of them: as this may probably be the case with you, I have undertaken the friendly office of mentioning them to you.

The World, Sir, in general allows you to be an honest good kind of Man enough, but you lose the Merit of this Character by an avaricious, miserly disposition which makes you guilty of many little dirty actions quite unbecoming the Character of a Gentleman, or the station you act in. People, Sir, see through this shallow artifice, and pity and despise you for it.

If you are a Man of common sense, you will make a proper use of this friendly admonition; if you are not, it is your own Fault; I have done my duty.

I am Sir

Your most obl. (tho’ unknown) servt.

Downright Honest [Phillip Turpin, 1779]