Terrestriality

On December 1, 2006, just past 18:30 GMT, Michael D. Griffin, Administrator of NASA, took the podium at the Royal Society of London. A physicist and engineer, Griffin nevertheless chose, at this event, to consider the history of the explorer’s body. “I’m not a historian,” he admitted, “but I am mindful of the lessons of history.” Griffin’s remarks were themselves historical, the most recent iteration in a long argument over an important question: is the human body innately terrestrial, unsuited to a prolonged time away from its earthly element?

Exploration is something that NASA and the Royal Society have in common. Griffin had participated in an earlier ceremony in which Stephen Hawking received the Royal Society’s Copley Medal. The award, which is always a great honor, carried extra glory in Hawking’s case: his medal had made a journey beyond the Earth and back on the Space Shuttle Discovery, named, as Griffin pointed out, after the Discovery that Captain James Cook had commanded on his second circumnavigation. Another shuttle, the Endeavour, was named for the first ship Cook had taken around the world. In 1776 Cook had won the Copley Medal for his efforts in combating sea scurvy during his circumnavigations. Griffin managed to square this circle of historical references by comparing the explorer’s old problem of sea scurvy to the new one of weightlessness in space:

This rate of bone loss for astronauts is ten times worse than for those who suffer from osteoporosis here on Earth. Thus, like sailors of the 18th century, our astronauts on the space station or in future missions to Mars face significant medical hazards in the form of bone fractures and kidney stones that could jeopardize their health and their mission. The equivalent of [antiscorbutic] sauerkraut for modern-day astronauts is the unpleasant but necessary nutrition and exercise regimen to create muscle tension and mitigate bone loss. But these are stopgaps, incomplete and unsatisfactory at best.

What Griffin didn’t know was that Cook hadn’t really solved the problem either. The sauerkraut story is a myth. Yet inside every bundle of historical clichés is an actual truth, and here it is.

During his two circumnavigations, Cook had indeed tackled scurvy, the plague of around-the-world expeditions since the very first, commanded (at least initially) by Ferdinand Magellan. Unlike space travel, these global circuits did not leave Earth—but they did depart terra firma. They were distinctive in the durations that their mariners spent at sea, combining all the hazards of single-ocean journeys into one long ordeal. This included passage over the dreaded Pacific, the world’s largest ocean, and the one with the fewest obvious stopping points, as would be apparent even to twentieth-century circumnavigators (Amelia Earhart’s life depended on her finding tiny Howland Island, which she failed to do.) During circumnavigations in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries it was impossible to guarantee timely access to land, even as supplies shrank and crew and ships fell apart. Much depended on luck. Poor survival rates were typical, as men died, deserted, or were abandoned:

| Men: Out/back | Attrition (%) | Ships: Out/back | Loss (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Magellan / Elcano (1519-22) |

275/39 | 86 | 5/1 | 80 |

| Loaísa (1524-32) |

450/9 | 98 | 8/0 | 100 |

| Drake (1577-80) |

164/56 | 66 | 5/1 | 80 |

| Noort (1598-1601) |

248/45 | 82 | 4/1 | 7/5 |

| Le Maire / Schouten (1615-16) |

87/21 | 76 | 2/0 | 100 |

| Dampier (1703-06) |

183/18 | 90 | 2/0 | 100 |

| Anson (1740-44) |

1,939/145 | 93 | 6/1 | 83 |

NASA’s website, like Griffin’s Royal Society speech, claims that it was Cook who beat the devil. The Endeavour “reportedly made the first long-distance voyage on which no crewman died from scurvy, the dietary disease caused by lack of ascorbic acids.” Moreover, “Cook is credited with being the first captain to use diet as a cure for scurvy, when he made his crew eat cress, sauerkraut and an orange extract.”

“No” on both counts. John Byron (grandfather of the poet) is the first circumnavigator credited with maintaining a scurvy-free ship, and the first to bring back the overwhelming majority of his men:

| Men | Deaths | Mortality (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Byron | 153 | 6 | 3.9 |

| Wallis/Carteret | 240 | 31 | 12.9 |

| Bougainville | 200 | 7 | 3.5 |

| Cook (I) | 96 | 40 | 41.7 |

| Cook (II) | 232 | 6 | 2.6 |

Nor were these happy outcomes the result of a dietetic magic bullet, either Cook’s fabled sauerkraut or the citrus that is frequently credited to naval doctor James Lind. Rather, circumnavigators thought that it was firm green earth that prevented (or cured) scurvy, and they accordingly thought of the disease as a kind of “earthsickness.” Iberian and French sailors coined that term by describing scurvy as “mal de tierra” or “mal de terre.” They did not mean that the earth made them sick (as “seasickness” means of the sea). They meant that their bodies pined for earth, much as a homesick person longs for home.

The idea of scurvy as earthsickness had existed since the sixteenth century. Whenever possible, circumnavigators put scorbutic invalids ashore to convalesce, to steep themselves in the air, water, and natural products of land. That was what Magellan did in Guam (in 1521), Olivier Van Noort in Brazil (1598), Joris Spilbergen also in Brazil (1614), William Dampier in the Galapagos (1684), Woodes Rogers at the Juan Fernández Islands (1709), and William Betagh on Cocos Island (1722). After his circumnavigation (1721-23), Dutch mariner Jacob Roggeveen stated that it took precisely “fourteen days on land” for “fresh” food and “the assisting land air” to cure scorbutic sailors.

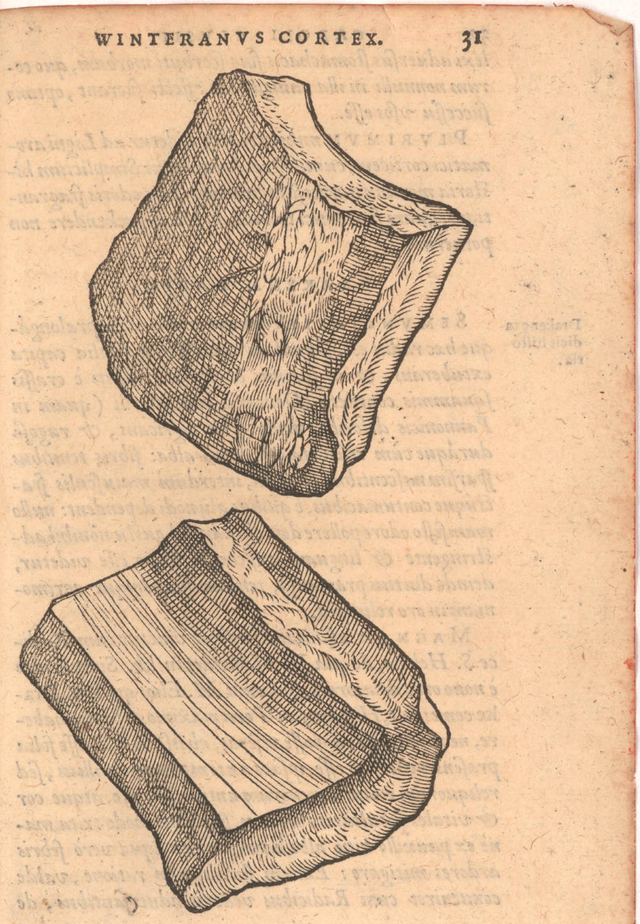

“Winter’s bark,” named after Captain William Winter, a colleague of Sir Francis Drake who used the bark to treat scurvy among his crew. Woodcut from Carolus Clusius, Rariorum aliquot stirpium per Hispanias observatarum historia, (1582). John Carter Brown Library

By the eighteenth century, mariners wondered whether a terrestrial essence could be preserved at sea by keeping the air below decks (as well as food and water stores) from losing a quality almost universally called “fresh.” Freshness usually indicated how recently something had been taken from land. One naval officer concluded that scurvy had only one “proper medicine: viz fresh meat and fruits.” At one Pacific island, George Anson’s men “eagerly devoured” a boatload of mown grass and butchered seals, both items “considered as fresh provision.” Conversely, heavily salted meat, the standard maritime ration, lacked freshness. If sailors had scurvy, “to give them salt provisions before they are thoroughly recovered, would be to murder them.” Indeed, the men “must inevitably perish without refreshments” derived from land, as if their sea provisions had, despite—or because of—their being salted, pickled, bottled, or confected, lost something in the translation.

Commentators were not always confident that the “refreshments” yielded the full benefit of being on land. They often jumbled the land’s virtues (sometimes but not always its air) with those of its fresh products. At Juan Fernández, “the land” but also “the refreshments it produces, very soon recover most stages of the sea-scurvy.” Relapsed cases benefitted from “the smell of the earth together with the coconut milk, oranges, limes, bread-fruit and fresh meat.” Sailors were “languishing” for “the land and its vegetable productions (an inclination that attended every stage of the sea-scurvy).” “Nor can all the physicians, with all their materia medica,” one mariner explained, “find a remedy for it equal to the smell of a turf or a dish of greens.”

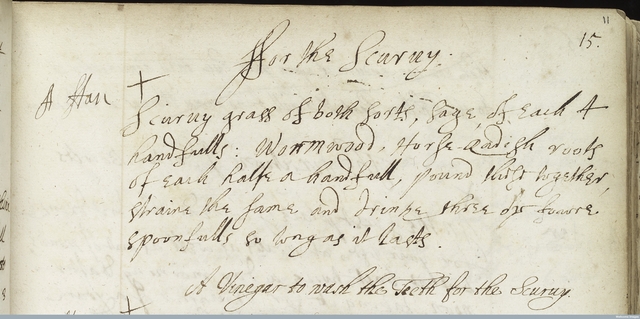

A scurvy remedy featuring scurvy grass, wormwood and horseradish from the recipe book of Lady Ann Fanshawe, wife of the English ambassador to Spain, 1651. Wellcome Trust

Why was land beneficial? Convinced they were right, most mariners did not bother to explain their claim. One of Anson’s officers concluded that humans had a terrestrial “Je ne sais quois … or in plain English, the land is man’s proper element, and vegetables and fruit his only physic”—the sailor’s basic belief, tricked out with a bit of French. Only it wasn’t unique to sailors; two eighteenth-century men of science agreed with it. Richard Mead said the speed of the land therapy was “incredible.” “Upon their being exposed upon the ground,” he claimed, Anson’s invalids “immediately recovered.” Mead related how one incapacitated sailor begged some stronger companions to dig a hole in the soil and let him inhale its restorative effluvia. “Upon doing this, he came to himself, and grew afterwards quite well.” In the third edition of his classic work on scurvy, Dr. James Lind (a purported citrus enthusiast) also defended the faith in land as something more than a sailor’s yarn. He described an incident when some scorbutic seamen were taken ashore, stripped, and buried up to their heads in the earth. They revived, Lind related, without a hint of skepticism. (The burial therapy was common for sea scurvy, as if graves in the earth could sometimes restore life to the dying rather than inter the dead.) Lind even thought that, given the melancholy that haunted the scorbutic, “the joy of being landed” was enough to begin their recovery.

The belief in earthsickness should frame the better-known storyline in which medical experts, including Lind, tried to identify a more precise cure for scurvy. Cook dutifully carried an arsenal of Admiralty-approved items believed to be antiscorbutic, including sauerkraut. But in the essay that brought him the Copley Prize, Cook declared that none of these items was itself sufficient to prevent scurvy. Reports from his third (and fatal) expedition, far from the Admiralty’s oversight, revealed how he and his men assumed that land and its fresh products were irreplaceable. Alexander Home, quartermaster on the voyage, in describing a brush with a poisonous plant in Kamchatka, marveled that it was “astonishing How we have Come to so little Damage in this way … for it was the Custom of Our Crews to Eat almost Every Herb plant Root and kinds of Fruit they Could Possibly Light [upon] with[out] the Least Inquirey or Hesitation or any Degree of skill & knowledge of their Qualitys.” Cook urged his sailors, wherever possible, to go ashore and pluck “A Handkerchif full of greens.” He would also “Order [the men] on shore in partys to walk about the Country and smell the Fresh Earth and Herbage,” as he himself did, to set an “Example.”

Sea scurvy receded into memory in the nineteenth century. Ships’ provisioning improved, but the critical factor was ability to make land. Cartographic knowledge of safe havens had improved, as did access to them. The Congress of Vienna (1815) declared that European nations should maintain free ports. Except in times of war, western countries—and, crucially, their imperial territories—welcomed ships of all nations. Travel became safer.

Charles Darwin recognized this when he rounded the world on the Beagle (1831-36). “How glad I am,” Darwin wrote home, that “the Beagle does not carry a years provisions; formerly it was like going into the grave for that time,” whereas he enjoyed frequent shore leave. “The short space of sixty years [since Captain Cook] has made an astonishing difference in the facility of distant navigation,” he concluded. “A yacht now with every luxury of life might circumnavigate the globe,” not least because “the whole western shores of America are thrown” open” and Australia settled. Humans could circle the Earth without compromising their attachment to earth.

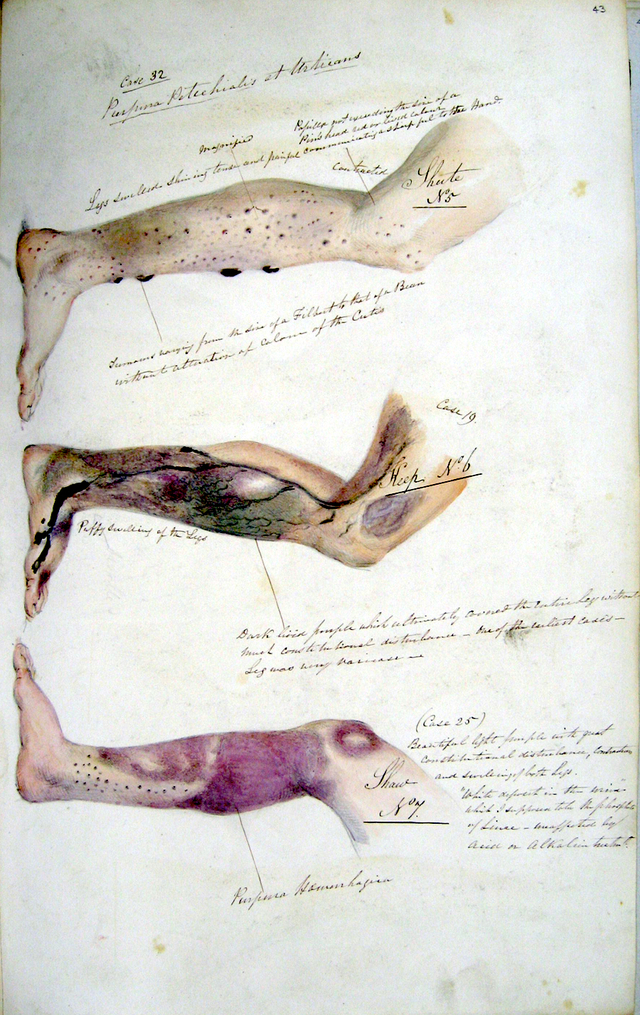

By the 1840s, when the naval surgeon Henry Walsh Mahon documented this case of scurvy on the Australia-bound convict ship Barrosa, the disease had become a relative rarity. The National Archives of the United Kingdom

A sense of the human body’s innate terrestriality may be maritime circumnavigation’s most powerful legacy. As Michael Griffin observed at the Royal Society, a spacecraft can be engineered to support human life: air and water can be recycled, waste removed, and humidity controlled. To that extent, spaceships and Spaceship Earth have similar optimal functioning. But the ships do nothing to counteract weightlessness, a problem for any prolonged time spent in space.

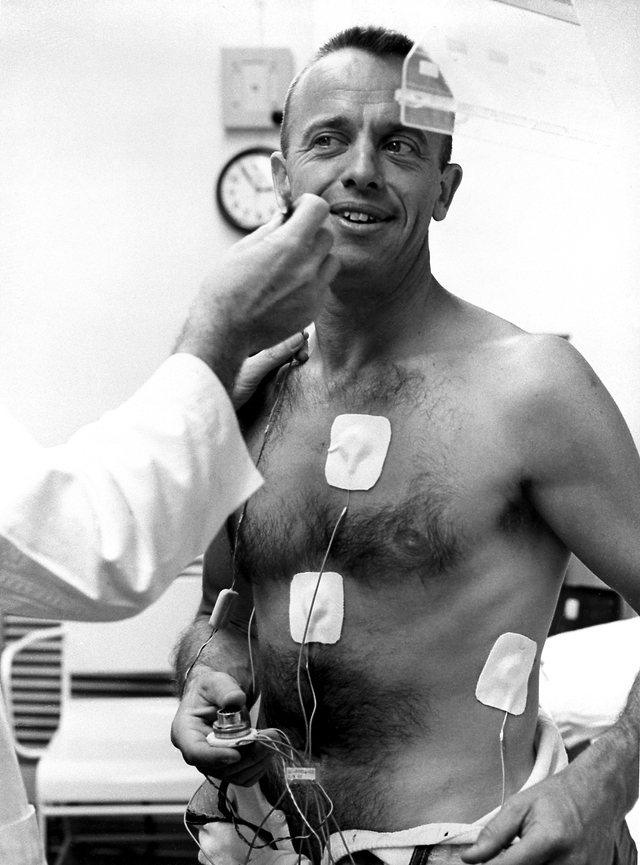

Because of mounting evidence that the human body deteriorates in orbit, Soviet cosmonauts on the first significant space station, Salyut, were required to do two hours of exercise each Earth day. Success with that regimen has made exercise a standard element of space-station life, the best therapy against bone loss and muscle and tissue deterioration. On Mir, a subsequent Soviet space station, Valeri Polyakov, who holds the record of longest stint in space, 438 days (1994 to 1995), exercised as frenziedly as a caged hamster running in a wheel. He returned in no worse shape than cosmonauts who weathered shorter space assignments. That set the bar low. After more than a week in orbit, most returning astronauts and cosmonauts can’t pull themselves from their capsules, let alone walk away from them.

Orbital experiments with plants and animals have been equally discouraging, even though life in space might require cultivation of food, rather than the extra-terrestrial equivalents of salt-beef (which in any case might have the nutritional content leeched from them by radiation). In 1971, Russians grew the first plants in space. Four years later, another Russian crew produced the first edible vegetables, onion sprouts. By 1982, a space-grown plant (Arabidiopsis, the lab rat of the plant world) produced seeds that germinated on Earth. By 1997, Mir produced only the second success (in twenty-six years) at growing plants with viable seeds. Animals fared even worse. Quail eggs hatched on Salyut produced headless chicks. In a later attempt on Mir, the chicks seemed healthy, but soon died.

The successful breeding of mammals in space is the gold standard, essential reassurance that prolonged weightlessness and exposure to elevated radiation would not medically compromise humans. So far, the full mammalian cycle, from conception to conception, hasn’t happened off Earth. It remains unclear whether humans, as mammals that live and reproduce in a terrestrial environment, could survive a long physical separation from Earth, unless altered into a “post-human” state.

NASA’s magic bullet scenario is seductive: just as sauerkraut (later, Vitamin C) cured scurvy, so medical regimens will combat weightlessness in orbit or the absence of gravity in space, and perhaps future remedies will be less intrusive and more portable. The equivalent of vitamin tablets against scurvy might be a space station that rotates just enough to generate a medically-meaningful level of artificial gravity.

But it took a long time to beat scurvy. More than 200 years divide Magellan’s deadly first circumnavigation from John Byron’s healthy one. And it wasn’t clear that the eighteenth century’s carefully-tested shipboard regimens, meant to preserve or pursue land’s fresh je ne sais quois, were what kept mortality low. The Congress of Vienna opened unprecedented territory (and fresh provisions) to circumnavigators after 1815, and frequent shore leave was a confounding variable. The first person to vindicate the claim that human life could be preserved at sea all the way around the world was Robin Knox Johnson, who completed the first solo, unassisted, nonstop circumnavigation in 1968, over 400 years after the return of Magellan’s survivors. Even if modern science could reduce that 400-year period by a quarter, to 100 years, we would still be at the halfway mark. That might be right, given the 26 years it took to replicate results in growing reproductive plant seeds in space, if we assume that humans are only four times as complicated as plants.

Advocates of space exploration often refer to the possibility that we may someday be forced to abandon our home planet. Leaving Earth will be the ultimate test of what makes us human. Are we essentially terrestrial? The earliest centuries of around-the-world travel generated copious evidence of humanity’s longing for the Earth. The scorbutic sailor desired the smell of fresh-cut turf and he rallied at the mere sight of a distant green island peak. A sense of innate terrestriality seemed deeply rooted in the body, not just to the eye or the mind, but within the gut, the flesh, the bone. Even if we might somehow survive elsewhere in the cosmos, we should probably take very good care of the Earth. We might miss it.

For a fuller treatment of this topic see Joyce Chaplin, Chaplin JE. “Earthsickness: Circumnavigation and the Terrestrial Human Body, 1520-1800,” Bulletin of the History of Medicine, 86/4, 2012.