Ditsong’s Dioramas: Putting a Body on a Fossil and a Fossil in a Narrative

His eyes were vacant—glassy, even. Blood flowed from his head and his hands dragged next to him, fingers rolling lifelessly in the brown African dirt. His mouth was frozen open in terror, his head firmly clenched between a leopard’s jaws. The cat’s snarl was practically audible. The scene was strangely mesmerizing and people stopped in their tracks to gawk. The horror, the horror. Another hominin bites the dust in the Ditsong Museum dioramas.

To most visitors, I would venture to guess, the Museum is a modern day cabinet of curiosities, chock-full of dinosaur fossils and taxidermied exotics. The most striking displays feature reconstructions of fossil human ancestors—the australopithecine hominins. Originally founded as the Staatsmuseum (State Museum) of the Zuid-Afrikaansche Republiek on 1 December 1892, the museum has amassed a colossal collection of artifacts and specimens from South Africa over the past 122 years.

In the early twentieth-century, the Staatsmuseum was renamed the Transvaal Museum and, in 2010, became the Ditsong Museum of Natural History. As a result of these changes, many exhibits at the Ditsong are receiving makeovers; the human evolution dioramas are no exception. The Museum curates some of South Africa’s most important fossil collections and many famous fossil human ancestors are brought to life through elaborate scenes based on the South African fossil record.

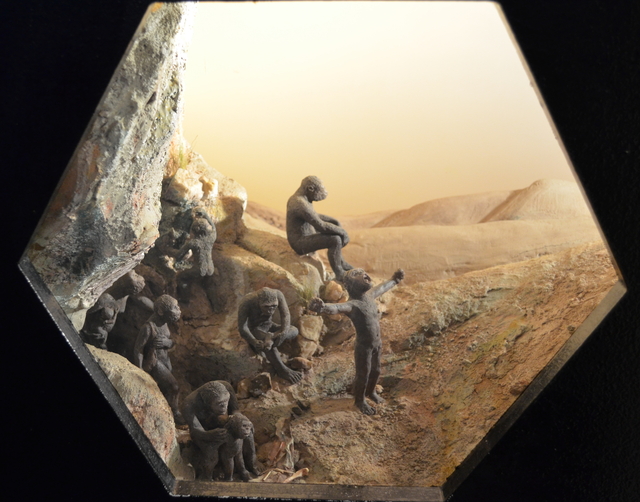

An early human ancestor in a contemplative moment, framed in one of the Ditsong Museum’s distinctive dioramas. Ditsong Museum, courtesy of J. Adams

The first time I visited the then-Transvaal museum, these dioramas showed the wear and tear of decades of display. Visitors saw exhibits with hominin hair a bit askew, tired-looking faux plants collecting dust, and models of australopithecine behavior that hadn’t really been in scientific vogue since the late 1960s. But the overall effect was oddly compelling. This past summer, I visited the Ditsong Museum again as part of a research trip to museums in Johannesburg and Pretoria. Despite their somewhat scrappy appearance, I was really looking forward to the Ditsong’s exhibit of australopithecine dioramas. On arrival I learned that the dioramas were closed to the public for cleaning, changing, and re-interpreting the evolutionary scenes.

What could the Ditsong dioramas have to offer?

Dioramas have a powerful explanatory power as tangible reconstructions. They take a static object, like a fossil, and give it a face and body. They transform the grimace of an ancient skull into an anthropomorphized face that looks back at us. We as viewers walk away understanding more through the diorama than if we simply read a descriptive placard about the fossil. Famous South African fossils like Mrs. Ples and the Taung Child find character, persona, and a voice through their public displays in the museum, in a South African museum even more so than other natural history venues.

In 1925, Australian anatomist, Raymond Dart, announced an unusual fossil from the northern province of South Africa. The fossil—a small crania and mandible—came from Buxton Limeworks quarry and arrived for Dart’s inspection buried in a crate of rocks. Dart and his wife, Dora, nicknamed the fossil the Taung Child and good-naturedly anthropomorphized it. “There was doubt if there was any parent prouder of his offspring,” Dart later recalled, “than I was of my Taungs baby [sic] on that Christmas of 1924.”

Upon its official publication in Nature, the scientific community dismissed the Taung fossil as a candidate for a human ancestor. Theories about the mechanics of human evolution in the 1920s pinned their hopes on the Piltdown fossil, found in Sussex in 1912 and later revealed as a hoax. According to evolutionary theory upheld by supporters of the Piltdown fossil, humans evolved big brains earlier than bipedality. The Taung Child, on the other hand, suggested that bipedality might be an earlier evolutionary trait than a large brain. Historical distance helps us to unpack the reasons that Piltdown was such a fossil contender in the hominin family tree—Piltdown privileged the Eurocentric historical vision of the day (It was only after Piltdown was shown to be a hoax in 1952 that the Taung Child became accepted as a human ancestor). Ultimately, the Taung fossil shifted the geographic emphasis of human evolution from Southeast Asia and Europe toward Africa, putting australopithecines on the map in scientific and public imaginations. Few fossils since have been simultaneously so scientifically important and publically iconic.

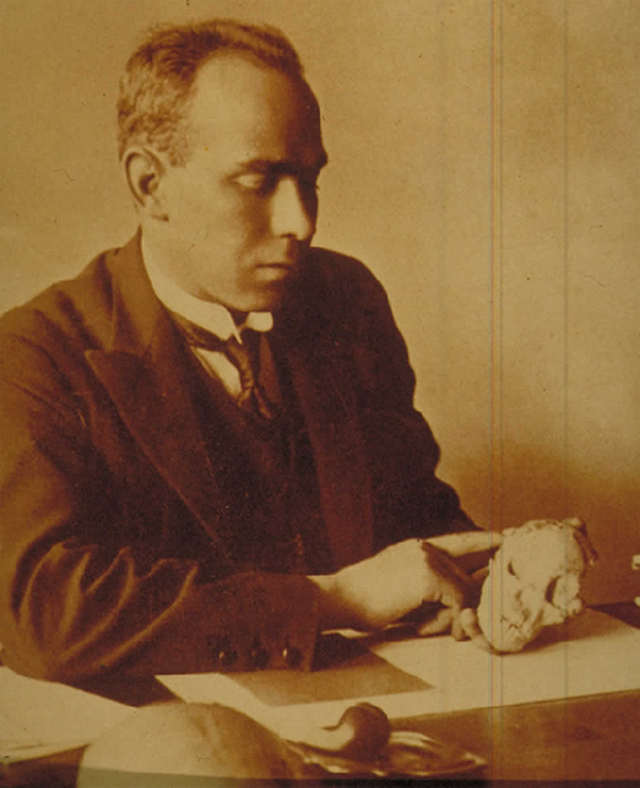

Raymond Dart with the Taung Child, immediately after his publication of the fossil in Nature, 1925. University of Witwatersrand, Raymond Dart Archive

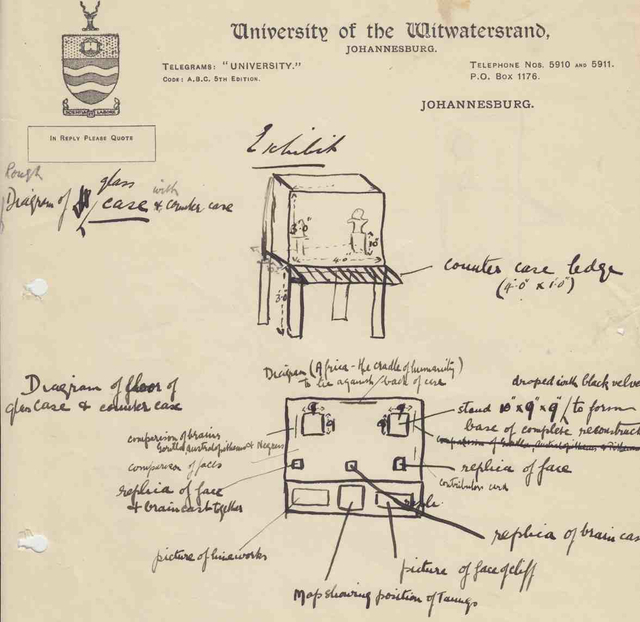

By 1925, Dart had created casts of the fossils which he promptly dispatched to Wembley, England as a contribution from South Africa toward the British Exhibition in 1925. The Exhibition Commission was most excited to show the casts, praising the exhibit Dart created: “We have had a good deal of attention drawn to this exhibit by the newspaper reports and we are indeed grateful to you for having framed such a nice cast.” The exhibit caused a stir within scientific circles because Dart argued the Taung fossil was a human ancestor and not some ape-like evolutionary offshoot—a decidedly anti-Piltdown argument. Prominent members of the paleo-intelligentsia, like Sir Arthur Keith, complained of being forced to parade through the public exhibit to examine the specimen rather than attend a special viewing for their own study. Prior to the exhibit, newspapers in England, South Africa, and as far away as Tasmania, played up the scientific rivalries and the question of the evolutionary legitimacy of the fossil, creating a huge public interest in actually seeing the crania cast at the British Exhibition. Dart recognized that the Taung Child had a public presence and spent a good deal of thought working out how to best display the fossil’s cast.

Raymond Dart’s sketch of the Taung cast display for Wembley and the British Exhibition, 1925. The author, courtesy of the University of Witwatersrand, Raymond Dart Archive

At the cost of a mere £15, cast replicas could be ordered by other institutions. The American Museum of Natural History queried Dart for one in the early 1930s. With a great deal of diplomatic tap-dancing, a set of casts even reached the Moscow Museum in 1933. Dart corresponded with other paleoanthropologists (like Franz Weidenreich, working in China), offering to trade a copy of the Taung Child’s cast. And Dart was inundated with numerous requests from Australia to Botswana for copies of Taung fossil for the museum to display to its visitors and to be accessible to its researchers—a human ancestor that so many had heard so much about.

Thanks to the newspapers’ interest in the fossil, the Taung Child thus gained a public as well as scientific life. People, even outside of scientific circles, had heard of the Taung Child. The cast became a way for scientists and museum-goers to put a face to the news reports of the Taung Child, itself. The cast was an equalizing object: expert and amateur fossil enthusiasts viewed the fossil casts together in spaces that did not differentiate according to education and expertise.

Dioramas and museum reconstructions, however, take us a step further than a simple cast. Reconstructions of extinct species—the australopithecines, in the case of Taung—became a way to put a body on a fossil. Fossil reconstructions evoke the tactility of muscle, skin, hair, and movement, providing a sense of “real-ness” that a mere description, however detailed, simply cannot match. Famous animals like Sir Roger the Elephant, in the Glasgow Museums collection, and Balto the Dog make the stories of these animals’ lives accessible, long after the animal is dead.

Putting a body on a fossil also puts a story on the science behind it. And setting this reconstruction of an extinct species in a larger diorama takes this one step further. The dioramas tell the viewer more than a plate or a placard repeating information from the scientific literature—it gives the viewer a narrative.

No one is exactly sure when Ditsong dioramas were first constructed, but most guesses put the dioramas as part of overhaul of the museum’s taxidermy and exhibits in the late 1960s. So what narratives surround the Ditsong dioramas? What stories are written into the fossil reconstructions and what are we to make of them?

In one corner, we see the stuffed leopard dragging an adult australopithecine off to its lair with the skull lodged firmly in its mouth. Blood drips from the tooth-punctures in the skull. (As a grad student, I used a photo of this very diorama scene as the background for my office name tag until my officemate made me take it down, claiming that it creeped her out and was off-putting to students.) In another corner, a different leopard sprawled on a tree branch, chewed on a juvenile australopith, where body limbs accumulated below the tree (suggesting perhaps that this was not the first small hominin to fall foul to predators).

A different section of the room showcases what appears to be a nuclear family: two parents playing with children, while keeping a watchful eye on the birds of prey perched above them. A small, furry moppet, labeled “Taung Child” toddles after his other family members.

Other scenes highlighted early tool-use, as adults brandished clubs. And a small in-wall diorama showed a stretching australopithecine, greeting the morning as others begin to awaken against a sun-kissed African horizon. It took a lot of restraint not to draw the Black Monolith from 2001: A Space Odyssey into that diorama’s background.

What narratives do these dioramas tell? And why are they important?

On the surface, it’s easy to dismiss such scenes. We can say that our scientific understanding of tool-making, social dynamics, and paleoenvironments has changed so much that we ought to dismiss these dioramas as vestiges of fifty-year-old science (for example, there is no paleo-evidence to support a depiction of the Taung Child in a nuclear family). It’s easy to argue that these dioramas are doing a disservice to museum-goers since the visitors will take away “wrong” information. It’s easy to take issue with the presentation of the reconstructions, saying that because the diorama stories are imprecise, it would be better to strip the scenes from the museum and only display fossil casts and their descriptions.

These stories, however, humanize the australopithecines, and that’s a powerful thing. It makes the fossil record accessible to us as people, not just as scientists. It makes us more sympathetic, more empathetic, with fossils we’re seeing. Just as we’re ready to look to the brandishing club as a clear cultural motif, courtesy of Stanley Kubrick, we’re prepared to allow human ancestors narratives that we wouldn’t have in other circumstances. Putting the body on these fossils speaks to the way that we consciously or unconsciously make sense of these scenes and human evolution more generally.

Ditsong Museum’s dioramas stand in stark contrast to the Smithsonian Institution’s Hall of Human Ancestors in Washington, D.C. While Ditsong has several entire scenes, there are only a few full-body reconstructions of human ancestors in the Smithsonian (most notably, of the famous Ethiopian fossil, Lucy). The reconstructed bodies and subsequent narratives of these ancestors have been stripped bare, back to the fossils’ casts. Instead of full diorama scenes, visitors see amazingly life-like reconstructions of hominin faces, created by brilliant paleo-artist John Gurche specifically for the Smithsonian. (Gurche’s hominin faces make just about every other attempt to put a body on a human ancestor look like a bedraggled 2001 extra sporting costume mange.) Interestingly and tellingly, for purposes of our diorama discussion, Gurche’s reconstructions are hominins that stand alone. There is an element of singularity and disconnect as the reconstructions stand as individuals, devoid of a scene and devoid of a story.

Interestingly, many of the specimens in the Hall of Human Ancestors have been reduced to their cast presence – there isn’t any attempt at a reconstruction. The Taung Child, for example, our famous South Africa fossil and lovable toddler from the Ditsong, cast stares unblinkingly at its viewer, devoid of any narrative. The small fossil is marooned without connections or context. This is a stark contrast to the Ditsong’s dioramas. Even in the original display of the fossil casts at Wembley, Raymond Dart dressed up the display with a black velvet backdrop, impressing upon the viewers that idea that they were seeing something valuable, like a venerated gem. In the Hall, there is none of that. In the Smithsonian display of the Taung Child, we can practically see Marcel Duchamp’s modernist series of glass—the Taung Child in the Hall of Human Ancestors shows us The Fossil Stripped Bare from its Narrative, Even.

Reconstructions of the fossil species are the means through which we internalize and make sense of the bare bone. And the face, the body, and eventually, a scene, allow us to be able to make sense of what we’re seeing through narratives that are familiar, stories that we can put ourselves into.

The dioramas at the Ditsong are still undergoing their cleaning and refurbishing and their future is in limbo. Perhaps the new displays will incorporate the most recent science of the fossils? Their diets? Their social structures? Their interactions with other animals in their ecosystems? It all makes me wonder what new narratives would be consciously or unconsciously written into the dioramas. A display without a narrative seems stark, cold, and inaccessible. I, for one, hope that the dioramas, in some narrative form or other, will continue to build powerful links between fossil and viewer.

The author would like to acknowledge Drexel University’s Pennoni Honors College; Dr. Justin Adams; Dr. Kevin Egan; Dr. Bernard Zipfel; Tesia Perregil of the Ditsong Archives; the Institute for Historical Studies at the University of Texas at Austin; and the feedback and editorial expertise from The Appendix.