Amazons, Pirates, and Turtles on the Island of California

I want you now to know a thing,

the strangest anyone could ever find

in either writing or memory…

Know that at the right hand of the Indies

very close to the Earthly Paradise…

there was an island called California

—Garcí Rodríguez de Montalvo, Las sergas de Esplandián, 1510

For centuries the Baja California peninsula was known as the Island of California, a mythical land populated by Amazons and griffins, covered in gold and pearls. Sea turtles swam in the surrounding Pacific Ocean and the Sea of Cortés, and have appeared in written and oral sources over four hundred years of the peninsula’s recorded history. Conquistadores, pirates, missionaries, whalers, and fishermen have, at different moments, relied on sea turtles for sustenance, commerce, and medicine. These sea turtles have an important place, both pragmatic and symbolic, in the history of the mythical “island.”

The Sagas of Esplandián

Tenochtitlán had fallen. The Spanish conquistadores, blinded by the unimagined riches torn from the empires of the Americas, stood before a New World seemingly unbound by the constraints of reality. The lines between the tangible and the imaginary became blurred. Literature played no small role in this entanglement. The chivalric novel, beloved by the masses of medieval Spain, stimulated the ambitions of the sailors and soldiers (often freed from gallows and dungeons) who crossed the Atlantic. This genre, parodied by Cervantes in Don Quixote, inspired colonial fantasies thanks to the novel, Las sergas de Esplandián (“The Sagas of Esplandián”) from whence was born the myth of the Island of California.

In Las sergas, the noble knight Esplandián survives the siege of Constantinople by a pagan horde of Amazons mounted on griffins, led by the queen, Calafia. They came from the Island of California, populated only by “black women… with valiant bodies and ardent hearts and great strength” whose weapons were made of gold because “in all of the island there was no other metal.” The novel was much admired by Cortés and his captains who, after the conquest of the Mexica or Aztec empire, would expand Spain’s empire northward in pursuit of the mythical geographies of El Dorado, Cíbola, and the Island of California. They did not find golden cities or Amazons in the Isle of California, but did encounter a vast, arid desert, and pearl-laden seas.

Sea turtles swarmed in great numbers around the “Island,” but proved to be of little interest to the conquistadores hungry for gold and Amazons. For millennia, turtles had constituted a staple food source for the Cochimí, Guaycura, and Pericú hunter-gatherers. However, when the Spanish first arrived in the 1500s, they faced starvation despite being surrounded by abundant food in the form of marine turtles. Over the next five centuries, the sea turtles would oscillate between the undesirable, the irresistible, and eventually the illicit, marking the broader environmental history of the Baja California peninsula.

Cortés’s Ill-fated Voyages

Cortés first received news of the Mexican Pacific, la Mar del Sur, in 1522, less than a year after the fall of México-Tenochtitlan and twelve years after Las sergas was published. In this time in which the real and the fantastic were closely intertwined, the conquistadores were quick to project a mythical geography onto the expanding landscape. In an effusive letter to Emperor Carlos V, he reported that

all those with any science and experience of the navigation of the Indies have had for very certain that, upon discovering these parts of the mar del Sur, there would be discovered and found many islands rich in gold and pearls and precious stones and spices, and there are to be discovered and found many secrets and admirable things.

Months later, his captain, Gonzalo de Sandoval, reported an island populated by women who killed their male offspring, and was said to be rich in pearls and gold, much like the island described in Las sergas. According to the novel, the Island of California was located “to the right hand of the Indies”—that is, to the east of Asia and to the west of New Spain—and seemed to be clearly situated off the coast of Cihuatlán, in the western provinces of New Spain. Cortés spent the next years sending expeditions in reconnaissance of the Mar del Sur, as far as the Philippines and the Moluccas. The unknown lands to the north—thought to be the location of the mythical Cíbola, El Dorado, and the Seven Cities of Gold—were surveyed by Spaniards. The Island of California, however, remained elusive.

A map of the “Mar del Zur” (the Spanish-controlled “South Seas”) by Jan Jansson, 1650. Glen McLaughlin Map Collection, courtesy Stanford University Libraries

In 1532, Cortés sent Captain Diego Hurtado on the first of many doomed expeditions; rather than a gold-paved island “close to the earthly paradise,” Hurtado and Company found a parched land surrounded by tempestuous seas. Other expeditions would follow. Francisco de Ulloa circumnavigated the small Sea of Cortés, along the Eastern edge of the “Island.” It became known as la mar Bermejo, the vermilion sea, for the reddish hue of its waters. He observed the naturales—hunter-gatherers of the Cochimí, Pericú, and Guaycura language groups—fishing from rafts with hooks fashioned from turtle bones, but never mentions consuming turtle himself.

In 1535, Cortés embarked on his third expedition to California in an attempt to establish a colony. After a reconnaissance voyage, Cortés sent for 320 people to be stationed in the mainland of New Spain, including 32 married couples, to settle in Bahía de la Santa Cruz (now known as the Bay of La Paz). Although the colonists did find pearls, there were no Amazons with golden weapons and the arid land proved too much of a challenge even for the hardened soldiers. According to Díaz del Castillo both Cortés and his soldiers were afflicted by the lack of food:

Throughout the land the naturales don’t gather corn, and they are a savage people… and all they eat are the fruits that are among them and fish and seafood. And of the soldiers that were with Cortés some died of hunger and… many more were in pain and cursing Cortés and his island and his sea and discovery.

It seems these early colonists weren’t eating the turtles. Although López de Gómara relates how the Californians “fish in the sea, with hooks or spines from trees, or bones of turtles, of which there are many and of great size.” However, he makes no mention of their consumption, saying that the Spaniards who were stationed at the port of Santa Cruz were starving, and over five had died of hunger. An average-sized turtle (50 kilograms) is relatively easy to catch from a small raft and could feed twenty grown men. However, López de Gómara states that the soldiers were emaciated to the point where they could no longer fish, and ate weeds and scarce wild fruits, despite simple access to this abundantly available food source. Spanish sources citing turtle consumption in the peninsula do not appear until much later, after the establishment of the Jesuit and Franciscan missions in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. It is unclear whether this initial aversion to sea turtle consumption was due to repulsion, or if the early Spaniards lacked the understanding that these giant turtles were a potential food source. However, this attitude would change over the centuries with the establishment of a mestizo society in the peninsula, to the point where sea turtles would become an iconic feature of regional gastronomy and culture.

The siege of the Manila ships

By the eighteenth century, Spain ruled un imperio en el que nunca se pone el sol (an empire where the sun never set), extending from Europe to America and across the Pacific to the Philippines. The trade route between Manila and Acapulco was well established. Trade ships returning to Acapulco spent four to six months traveling from Manila to New Spain. They returned laden with silk, spices, porcelain, and treasures. These goods were bought with Mexican silver and came from Persia to Japan, purchased through the trade centers of the Philippines. By the end of the long trade journeys, the crews were famished and scurvy-ridden; large sums were sometimes paid for the fresh meat of rats that scuttled about the ships. With little or no naval escort or stopover points on the return voyage, the galleons were vulnerable to attack. Buccaneers and corsairs knew this well. They roamed the waters around Cape San Lucas, the first small port town at which galleons often made landfall after months at sea, waiting for the treasure ships. Their diaries are valuable records of the ethnography and natural history of the “Island of California” and the Sea of Cortés.

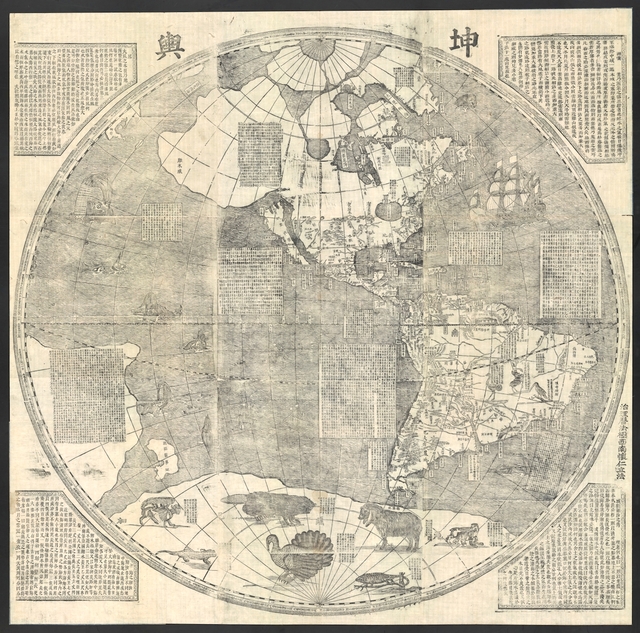

A woodblock map published in Beijing in 1674 under the direction of the Jesuit missionary Ferdinand Verbiest shows California as an island—as well as an Antarctic turkey. Glen McLaughlin Map Collection, Stanford University Libraries

Sea turtles were an important part of the buccaneer diet, mainly because they could be held alive, without water, for weeks or months at a time. The diaries of corsairs like George Anson, Edward Cooke, and Woodes Rogers contain detailed descriptions of where, how, and how many turtles were caught on the stops between Lima and Cape San Lucas. There, turtles were consumed as they waited for the Manila ships. Recounting his time in the Marías Archipelago, in the sea of Cortez, Edward Cooke offers up a reminiscence that is in equal parts gastronomy and natural history, using the words “turtle” and “tortoise” indistinctly:

The Lean of the green Tortoise taste and looks like Veal, without any Fishy Savour; the Fat is as green as Grass, and very sweet; the Belly, either bak’d or roasted, is excellent Food. We sometimes took 100 tortoises in one Night a-shore, and kept some of them six Weeks without Meat or Water. They are easily taken at Sea, when it is their breeding Time.

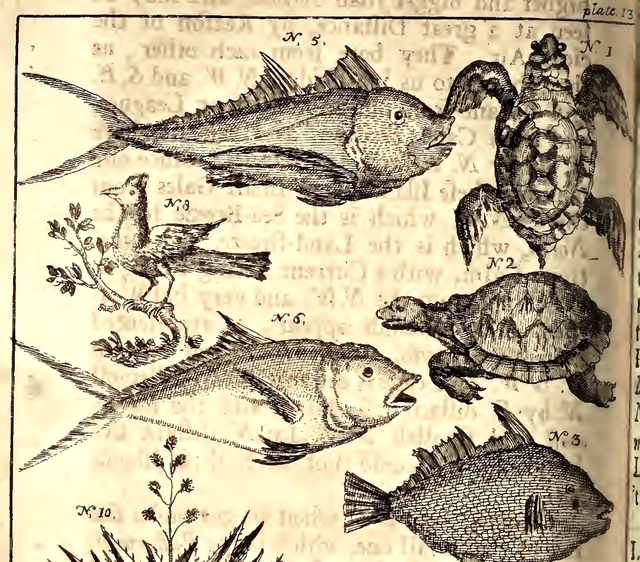

Along with this, Cooke provided some of the first illustrations of the animals of the Marías Archipelago, including a sea turtle that is probably Chelonia mydas or Lepidochelys olivacea. Rogers added a tentative taxonomic description:

The Turtle here is very good, but of a different Shape from any I have seen; and tho’ vulgarly there’s reckon’d but 3 sorts of Turtle, we have seen 6 or 7 different sorts at several times, and our People have eat of them all.

This statement seems to indicate that the creature in question is not the green turtle (Chelonia mydas), abundant in Caribbean waters and preferred by British taste-makers. These passages seem to describe the nesting habits of Lepidochelys olivacea, the Olive Ridley sea turtle. If so, this is probably the earliest written description of sea turtle synchronous mass nesting behavior in the Eastern Pacific region.

Sea turtles, probably Chelonia mydas or Lepidochelys olivacea, depicted in an engraving in Edward Cooke’s A Voyage to the South Sea (London, 1712). The Internet Archive

Another British corsair, Admiral George Anson, discusses the virtues of turtle as a nourishing and salubrious food despite the fact that Spaniards were adverse to its consumption:

It appears wonderful that a species of food very palatable and salubrious as turtle, and there so much abounding, should be prescribed by the Spaniards as unwholesome, and little less than poisonous. Perhaps the strange appearance of this animal may have been the foundation of this ridiculous and superstitious aversion, which is strongly rooted in the inhabitants of those countries, and of which we had many instances during the course of this navigation.

Anson’s observations of the Spanish aversion to turtle consumption may shed light on the case of Cortés’s colonization attempts. Although an average-sized East Pacific green sea turtle could feed twenty grown men, much of Cortés’s party starved to death. Spanish sources citing turtle consumption in the peninsula do not appear until much later, and the idea of the turtle as “unwholesome, little less than poison” may have contributed to this lacuna.

While the Spanish were reluctant to consume sea turtles, the British felt no such disinclination. James Colnett, a whaler on a voyage to expand the spermaceti industry, described the sea around Cape San Lucas as “almost covered with turtles, and other tropical fish.” Turtles were a valuable source of food for his crew. Their dependence upon it was such that his crew grew tired of turtle soup cooked with salt meats. Undaunted, Colnett “gave them flour to make their turtle-meats into pies, and, at other times, fat pork to chop up with it, and make sausages.” Although it was rumored that living on turtle caused the flux, scurvy, or fever, Colnett prevented sickness by allowing “the crew as much vinegar as they could use, and superintend myself the preparation of the seaman’s meal… But in most of their messes, I took care that so powerful an antiseptic, as sour crout, should not be forgotten.”

This extensive sea turtle consumption among British mariners stands in stark contrast with the reticence—or at least omission from records—regarding turtles among the Spanish. Is it possible that a few turtles could have changed the fate of Cortés’s doomed attempt to subdue the Island of California?

A turtle surmounts the cartouche (decorative illustration surrounding the title) of Jan Jansson’s 1650 map of the South Seas. Glen McLaughlin Map Collection, courtesy Stanford University Libraries

Californios, Whalers and Canneries

It took nearly two hundred years for the Spanish to establish a stronghold on the Baja California peninsula. The Spanish presence was dominated by the need for safe ports on the Manila Galleons’ return voyages in trade routes. By then, Jesuit and Franciscan missionaries, aided by Spanish soldiers in the task of expanding the empire, had established a network of precarious agrarian settlements that stretched from Cape San Lucas to the south to Cape Mendocino to the north. Indigenous Baja Californian hunter-gatherer populations were quickly decimated by disease and famine, and by the early nineteenth century a small but distinctive Californio society had emerged from the descendants of the native peoples, Spanish soldiers, and shipwrecked and mutinied sailors from Europe, Asia, and the United States.

Early missionary documents register an aversion to sea turtle consumption by the colonists, following the tendencies recorded in the initial Spanish voyages of the sixteenth century. Miguel del Barco, one of the most important chroniclers of Californian life and natural history, states in the late eighteenth century that “only the indios consume them, and reek with a particular stench of seafood.” However his contemporary, the Bohemian Jesuit Wenceslaos Linck, mentions eating turtle out of necessity:

Had not the Gulf of California and the Pacific Ocean—some twenty hours distant from each other—furnished [the natives] with fish, mollusks, oysters, turtles and other sea food, both they and the missionary would have starved—so little did the land produce.

Unfortunately, very few specifics are known about how indigenous Californians exploited sea turtles. Aside from eating them and using their bones as hooks and their guts and bladders for carrying water, there are no ethnohistoric records of cooking methods or medicinal uses. However, it is likely that as Californio society emerged from the colonial processes of mestizaje between the Spanish colonists and native hunter-gatherers, so did the dominant attitudes towards consuming sea turtles—caguamas—which became a defining element of Californio life. Besides being a traditional food (ethnographic fieldwork has yielded over forty recipes in two communities alone) sea turtles were used as medicine, the rendered fat or oil being used as a remedy for coughs, asthma, and bronchial disease, while fresh turtle blood was used as a remedy for anemia. Sea turtle oil was also used in traditional tannery methods.

During the 1850s, American and Russian whalers began hunting gray whales (Eschrichtius robustus) in the Baja California lagoons. Some whalers would abandon ship and stay on in the peninsula, adapting to Californio life; others would continue onward to the ports of San Francisco, Kamchatka and Nantucket. Sea turtles provided sustenance on the whaling voyages and, as global whale stocks plummeted and voyages became less profitable, sea turtles could supplement meager earnings from sperm oil and rendered blubber. By the late nineteenth century, green turtles from Baja California lagoons were being shipped to restaurants in San Francisco and Chicago by whaling vessels.

Captain Charles Scammon, one of the first naturalists to make detailed descriptions of Cetacean biology, lyrically describes the abundance of the Baja California lagoons:

The brig Boston … on a whaling, sea, and sea-elephant voyage … traversed this hitherto unknown whaling-ground. At that time the waters were alive with whales, porpoises, and fish of many varieties; turtle and seal basked upon the shores.

Grey whale populations were quickly decimated, and within less than twenty years whaling fleets abandoned the lagoons along the Baja California coast. Sea turtles, however, remained abundant. During the early twentieth century, fishing vessels from the United States captured East Pacific green turtles—up to a thousand per month—from along the Pacific Shore for processing in canneries in San Diego. By the 1930s, turtles were completely extirpated from Magdalena Bay and Turtle Bay, in Baja California Sur, Mexico.

Caldo de caguama

Throughout the second half of the twentieth century, sea turtles were fished commercially along Baja California coasts to feed a demand for turtle meat in the growing cities along the Mexico-U.S. border. As the Baja Californian cities of Tijuana, Ensenada, and Mexicali grew, caguamerías selling sea turtle soup, caldo de caguama (also referred to simply as caguama), appeared on streets and in markets. Caldo de caguama begins with sea turtle, an indigenous ingredient, combined with foods introduced by the missionaries: Mediterranean crops and products such as red wine made from Baja Californian grapes, olives, and wheat, as well as Mesoamerican crops such as chilies and tomatoes. Caldo de caguama incorporates all of these elements and is cooked in a slow and elaborate process that takes over six hours from the butcher’s block to the plate. It is consumed with flour tortillas, traditionally made in some communities with rendered turtle fat and sea water. This and many other sea turtle recipes have been kept as part of an oral tradition for generations, perhaps since the time of the missions.

Fishermen hold up a large East Pacific green turtle (Chelonia mydas), circa 1950 Galván family of Bahía de los Ángeles, Baja California, Mexico

During much of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, caguamas were a staple food in many isolated communities. Aside from elaborate dishes, sea turtle meat was dried as jerky (machaca de caguama) or roasted in its shell over open fire. Aletas rellenas, breaded flippers stuffed with picadillo –a mixture of beef, olives, raisins, and spices– were a representative festive dish. Sea turtles also replaced beef and chicken in other recipes such as bistec ranchero or milanesas. Every part of the turtle was utilized, from the meat, blood, and offal to the carapace, which was boiled down to a gelatinous consistency. Different sauces were used for each type of offal: the heart, tripe, and the prized, creamy liver. Fat was rendered for making crisp chicharrón, and also used to replace lard in times of scarcity. Sea turtle consumption became so ubiquitous in Baja California communities that David Caldwell, a marine biologist who worked in the peninsula in the 1960s, described it as “the black steer of Baja California.” Caguama’s status as an iconic, staple ingredient in post-colonial Baja California contrasts sharply with the initial aversions of the early Spanish colonists.

The roles of sea turtles in California have changed alongside human interpretations and interactions with the Californian environment. First a staple food source for hunter-gatherers, they were both reviled and beloved by European colonists and sailors. The formation of a Californio society from the eighteenth century onward brought about a change of paradigm in regards to sea turtles: they became a beloved ingredient, as well as a necessary food source for survival in isolated desert communities.

Today, sea turtles are a contradictory symbol of Baja Californian tradition and, simultaneously, a contentious object of illegality as captures have been banned since 1990. Although the law is not enforced consistently, sea turtle poaching can be punished by up to nine years in prison. However, sea turtle dishes are consumed at many important social and life events—weddings, baptisms, and quinceañeras (a large party and coming-of-age ceremony held on a girl’s 15th birthday) in communities across the peninsula. Despite caguama consumption remaining relatively common yet discrete, it is less embedded among younger generations that have grown up after the ban. Although this has been favorable for populations of Chelonia mydas, some elders fear that as caguama consumption is lost, the recipes, and the tradition and social cohesion associated with them, will be lost as well. Today, East Pacific green turtle populations that feed in Baja California are showing initial signs of recovery after over twenty years of diminished fishing pressure and nesting beach protection. Caguama, once unpalatable, later irresistible, and now illegal, remains an edible connection to the complex history of the “Island” of California.

Acknowledgements:

The author would like to acknowledge the Graduate Program in Ocean Sciences and Limnology at the National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM). Research was funded by Consejo Nacional de Ciencia y Tecnología (CONACyT) graduate studies grant no. 289695. Fieldwork was funded by Grupo Tortuguero de las Californias, A.C. The author acknowledges and thanks all the fishermen who opened their homes and shared their experiences, as well as the personnel of the Área Natural Protegida de Flora y Fauna Islas del Golfo de California, El Vizcaíno Biosphere Reserve, and Museo de Naturaleza y Cultura de Bahía de los Ángeles. The author also thanks Erik Vance and editors Lydia Pyne and Marissa Nicosia for their thoughtful comments and contributions.

Further reading:

This article pairs well with India Mandelkern’s 2013 Appendix article “The Politics of the Turtle Feast.”