The Space Between

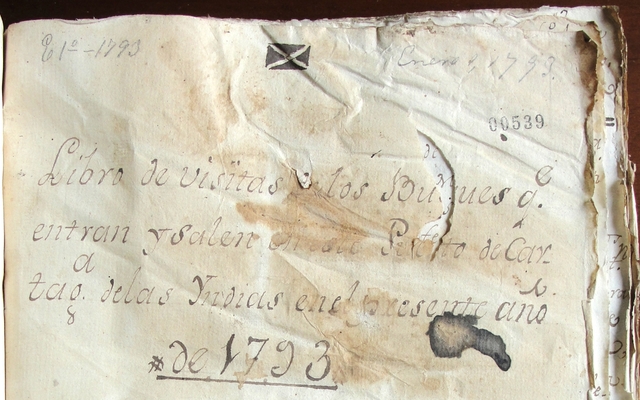

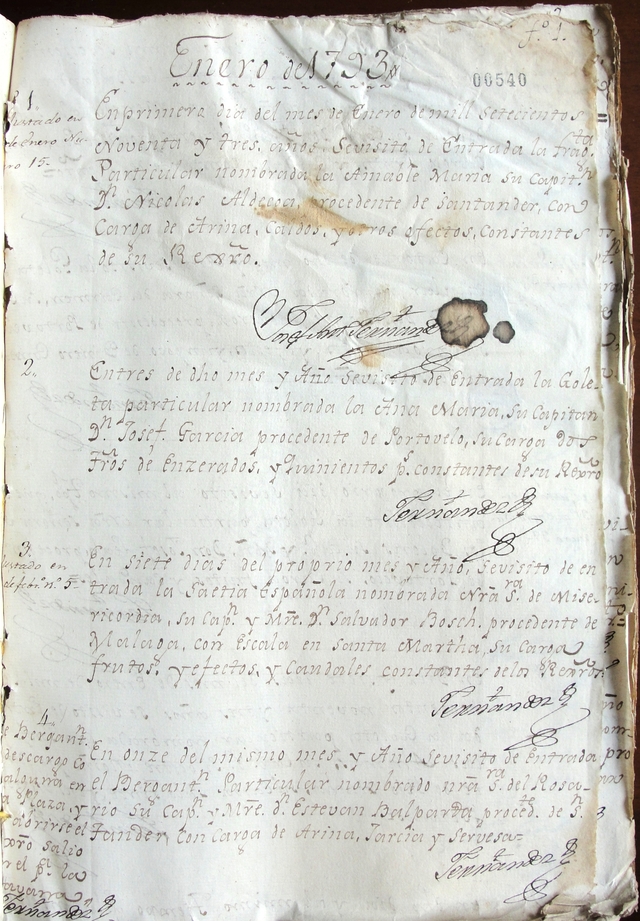

Title page of Cartagena’s 1793 book of ship arrivals and departures. Archivo General de la Nación, Bogota, Colombia. Archivo Anexo 1, Aduanas, 22, 539-569

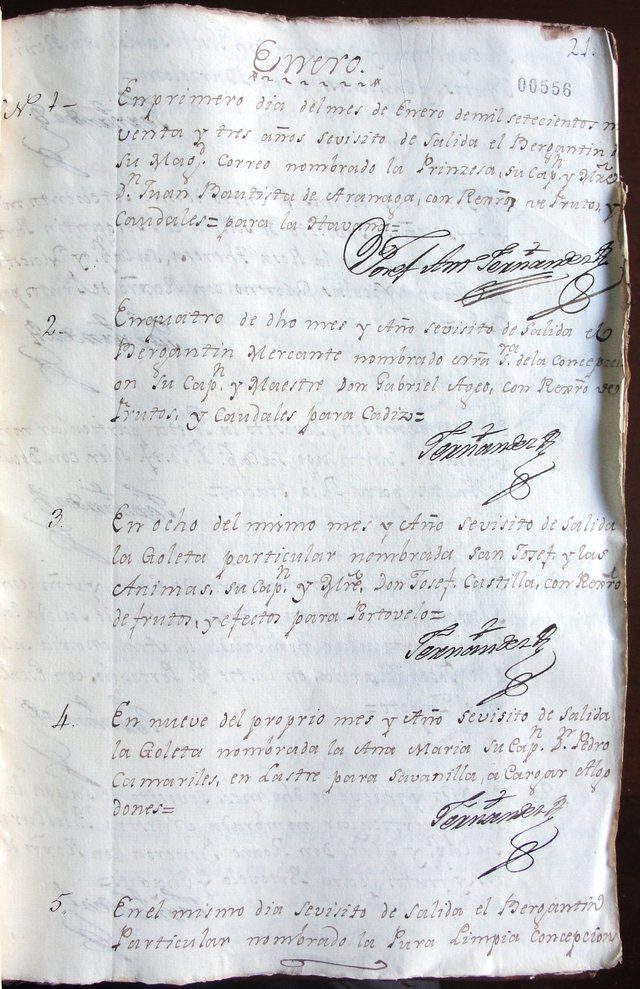

Sample pages of Cartagena’s 1793 book of arrivals and departures. Archivo General de la Nación, Bogota, Colombia. Archivo Anexo 1, Aduanas, 22, 539-569

Sample pages of Cartagena’s 1793 book of arrivals and departures. Archivo General de la Nación, Bogota, Colombia. Archivo Anexo 1, Aduanas, 22, 539-569

On January 9, 1793, the schooner Ana María, captained by Pedro Camariles, sailed from Cartagena to Sabanilla. In Sabanilla (so it declared when leaving Cartagena) it was going to load cotton, most likely to sell later in Jamaica or in another foreign colony. This much we can know from a single entry into shipping returns like the one pictured above.

In theory, shipping returns, also called books of arrivals and departures, register every legal arrival into and departure from a particular port. Much like modern airport arrival and departure screens, shipping returns give us a sense of the ways in which a particular port was connected with the world. Shipping returns list the name of the ship’s captain, the ship’s nationality, its port of origin or destination, and a brief description of its cargo. On occasion, they also include the tonnage of the ship and a short note regarding unusual circumstances accounting for a ship’s arrival (it was common to make a note about ships that entered after being captured at sea as well as those that entered de arribada or in distress).

In an ideal world, one might piece together thousands of records like that of the Ana María to get a complete picture of the workings of the maritime networks connecting Cartagena (or any other port) to the wider world. Such a reconstruction, in turn, would provide a clear picture of the geographic space that sailors and other frequent travelers inhabited. But that assumes that these records exist for all ships. And it assumes that all ships’ movements were recorded.

Following ships in the archives, tracing the routes of the sloops and schooners that navigated the Caribbean during the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, is a difficult task. The problem—mostly—has to do with the fragmentary nature of the information available in archival repositories. Neither the Spanish colonial archives (I worked at Seville’s Archivo General de Indias and Colombia’s Archivo General de la Nación) nor the UK’s National Archives allow for a complete reconstruction of the dynamic world of transimperial exchanges in which New Granada’s Caribbean ports were actively involved.

Shipping returns, to begin with, are only available for selected ports and selected years. In addition, because many ships sailed the Caribbean carrying contraband, their owners, captains, and sailors made conscious efforts to avoid colonial authorities and, by extension, the colonial archive. A certain lack of imagination when it came to naming ships—or religious scruples demanding seamen to seek heavenly protection when braving the seas—adds difficulty to the task of following ships as they navigated Caribbean waters. Names like San Josef (or San Joseph or San Josef y las Ánimas and many other variations) and Carmen (or Nuestra Señora del Carmen or El Carmen and many variations thereof) were very common. With multiple ships bearing the same name it is often impossible to avoid confusion and successfully follow the maritime path and archival trail of a specific ship. Sometimes ship aliases, captain names, and tonnage are helpful in distinguishing between two ships of the same name. But aliases and tonnage are not always available. And frequent changes of captains, sometimes unaccounted for in the shipping returns, do not always make it easy to distinguish between two schooners called Nuestra Señora del Carmen. Add to this other issues, including flag changes, sales that lead to renaming, and shipwrecks, and you could imagine maritime historians finding themselves lost at sea while trying to follow a ship across the seas.

Even in cases where shipping returns yield what seems to be a detailed itinerary of a ship’s Caribbean cruise, a careful look at the arrival and departure dates reveals moments in which the ship “gets lost.” Where does a ship go when it temporarily disappears from the archival record? It enters the space between. That is, the geographic area and the time elapsed between the moments of visibility afforded by shipping returns. While shipping returns allow us to see ships entering and leaving ports, much of their actual journeys remains invisible. What happens in between ports is concealed from the historian’s gaze unless the ship encounters troubles that put it again on the archival record. Sometimes the space between falls well between the parameters of what can be considered normal. Often, it does not. This is when things get interesting.

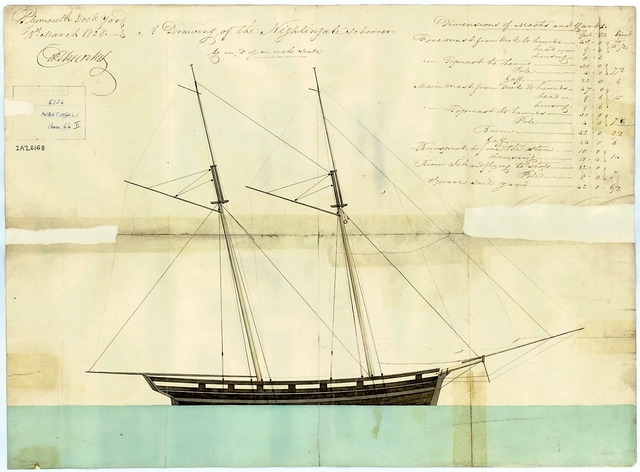

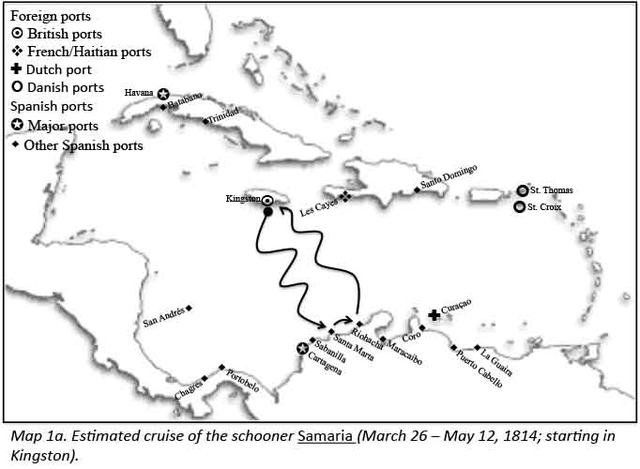

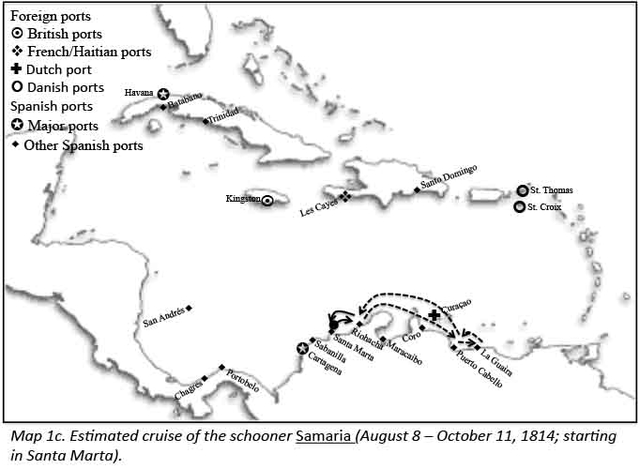

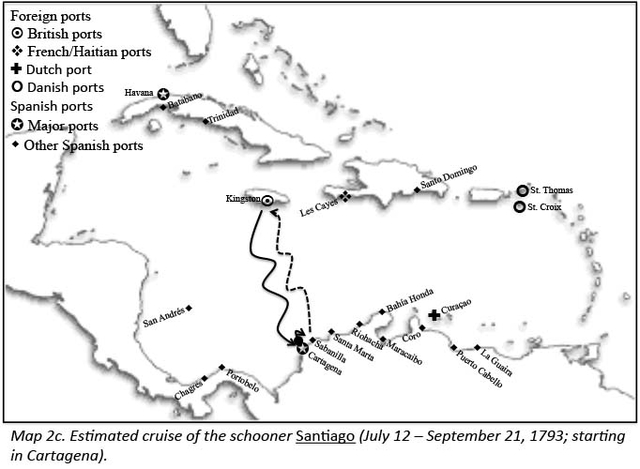

The visible trajectories of two schooners, the Samaria and the Santiago, demonstrate the possibilities and limitations of shipping returns. They also show the almost limitless possibilities of the space between. Maps 1a to 1d depict the estimated cruise of the schooner Samaria during 1814. The Samaria’s documented cruise began in Kingston on March 26. Eleven days later it entered Santa Marta, on April 6, carrying rum, candles, and dry goods. After two weeks in Santa Marta it sailed, in ballast, toward Riohacha. The Samaria’s next documented sighting was in Kingston, on May 12, which it entered loaded with Nicaragua wood, a cargo commonly found in ships entering Kingston, Cartagena, and Santa Marta from Riohacha. There is no registry of the Samaria entering or leaving Riohacha. In fact, there are no port records available for Riohacha at all. Still, the twenty-two days that elapsed between its departure from Santa Marta and its arrival at Kingston make its declared Santa Marta-Riohacha-Kingston itinerary credible. The path traversed by the Samaria between Santa Marta and Kingston seems to have been—as declared—the seaspace between Santa Marta and Riohacha, the port of Riohacha itself, and the seaspace between Riohacha and Kingston.

Nine days after sailing from Kingston on May 21, again carrying rum and dry goods, the Samaria entered Santa Marta. After a twenty-day stopover it sailed, in ballast, from Santa Marta to Riohacha and Maracaibo. Forty days later, on July 30, it entered Santa Marta from Riohacha with registro from Maracaibo (registro refers to paperwork and merchandise that confirmed that it actually was in Maracaibo). Even in the absence of shipping returns for Riohacha and Maracaibo, the fact that it entered Santa Marta with registro from Maracaibo gives credence to the itinerary depicted in map 1b. In addition, assuming navigation times of about a week for each of the four steps of the Santa Marta-Riohacha-Maracaibo-Riohacha-Santa Marta journey, and stays in port of about five days, the forty days elapsed between its departure from Santa Marta and its return to the same port further add credibility to the Samaria’s declared itinerary. Nevertheless, one wonders.

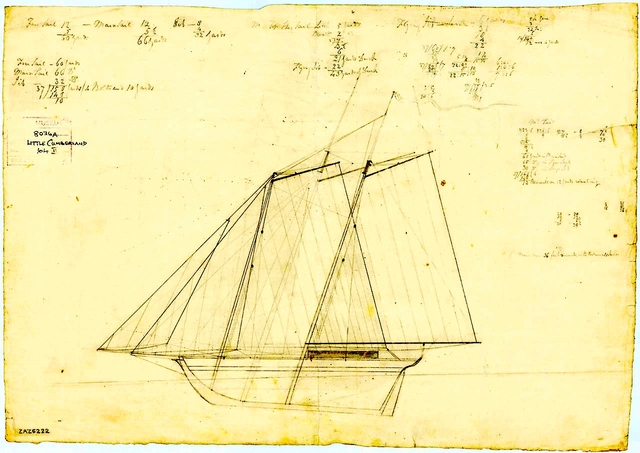

The next steps in the Samaria’s 1814 journey (map 1c) involve two new ports: La Guaira and Puerto Cabello. In this case, the space between gets murky. Shipping returns only show that it sailed from Santa Marta to Riohacha on August 8 and, two months later, on October 11, returned to Santa Marta from Riohacha with registro from La Guaira and Puerto Cabello. Did the Samaria follow the Santa Marta-Riohacha-Puerto Cabello-La Guaira-Puerto Cabello-Riohacha-Santa Marta route that the shipping returns imply? The registro from La Guaira and Puerto Cabello proves that the Samaria visited these two ports. The order in which it entered them, and potential visits to other Spanish or foreign ports, cannot be verified. The conspicuousness of contraband in the area raises suspicions about the likelihood of the Samaria actually following its stated route. Dutch merchants from Curaçao and the indigenous Wayuu of the Province of Riohacha were known to be actively engaged in this illicit trade. Proving these suspicions, however, is not possible.

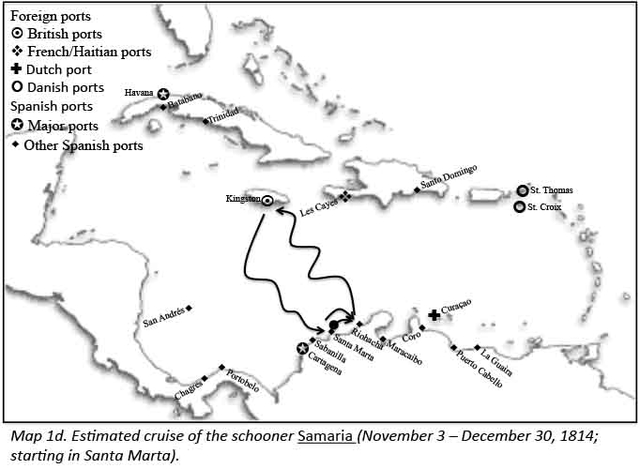

The last portion of the schooner’s 1814 journey is far clearer. After sailing from Santa Marta to Riohacha on November 3, records show it entered Kingston, from Riohacha, on November 16. Eight days later, on November 24, it sailed from Kingston to Santa Marta, entering this last port (declaring that it was coming from Kingston) on December 1. On December 20, it sailed from Santa Marta to Riohacha, only to return two days later claiming that strong winds made it impossible to continue its journey. After a week docked in Santa Marta, the Samaria began its last trip of 1814, sailing to Riohacha on December 30.

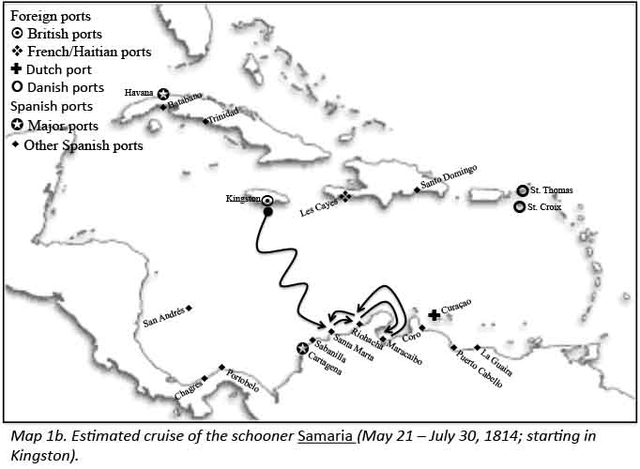

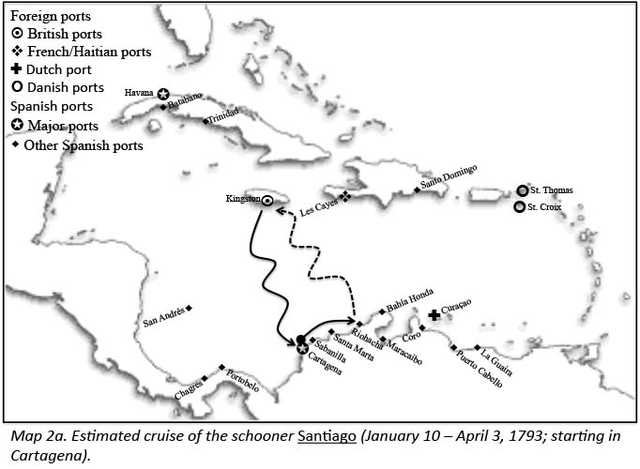

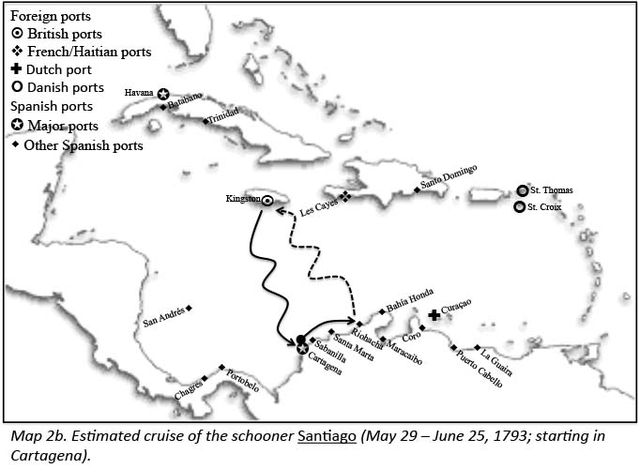

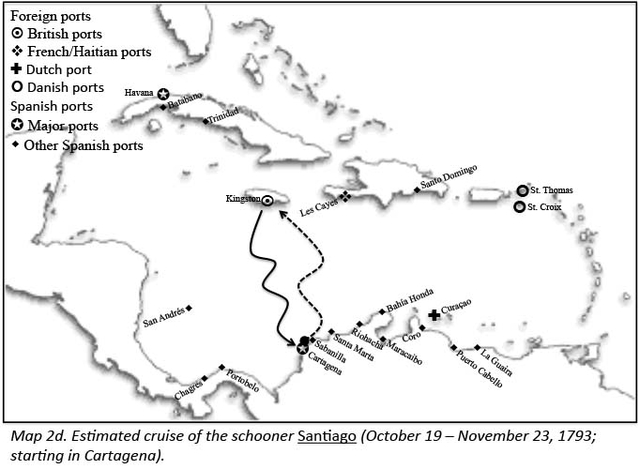

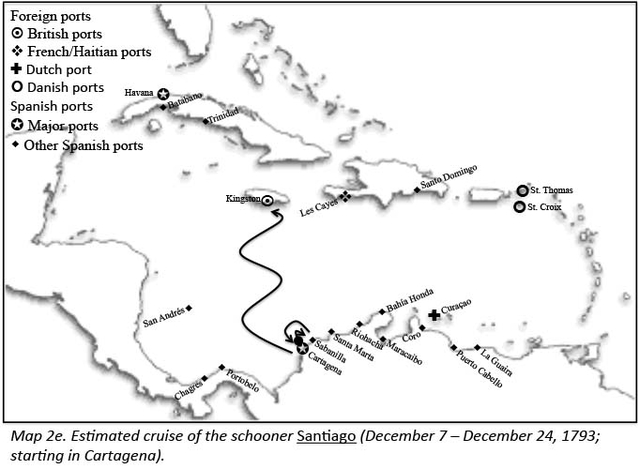

The retrievable itinerary of the Santiago (maps 2a-2e) provides a better sense of the possibilities of the space between. From January 10, 1793, when it sailed from Cartagena to Riohacha with frutos (agricultural produce) to December 24, when it sailed from Cartagena to Kingston (again with frutos), the Santiago frequently crisscrossed the seaspace between Jamaica and the Caribbean coast of New Granada. Its declared itinerary includes repeated visits to Kingston, Cartagena, Riohacha, and the small port of Sabanilla. But the Santiago’s 1793 journey is full of holes—the kind that make a historian wonder what might have happened in the vast spaces between its documented entries in Cartagena’s book of arrivals and departures. During the first half of the year, for instance, the Santiago appears to have followed two identical triangular paths sailing from Cartagena to Riohacha, from Riohacha to Jamaica, and from Jamaica to Cartagena.

Appearances, in this case, can be deceiving. Shipping returns only provide certainty about four dates:

1) January 10, when the Santiago sailed from Cartagena declaring that it was sailing to Riohacha;

2) April 3, when it entered Cartagena from Jamaica;

3) May 29, when it left Cartagena declaring Riohacha as its destination; and

4) June 25, when, once again, it entered Cartagena from Jamaica.

It is tempting to fill the gaps in this itinerary with two straightforward trips from Riohacha to Jamaica in order to complete the triangular path suggested by Cartagena’s shipping returns. While this is a possibility, there are other plausible scenarios. Did the Santiago actually sail to Riohacha both times? If it did, what port did it visit next? Did it sail from Riohacha to Jamaica or did it sail to another foreign port? If, in fact, it followed the same path on both occasions, why did it take it almost two months to return to Cartagena the first time and less than a month the second time?

The space between, here, bursts with possibilities: delays in Riohacha and Kingston linked to procuring supplies and commodities; weather, in the form of rough seas or complete lack of wind; harassment by foreign ships at sea; undeclared trips to other foreign ports to procure foreign (mostly British) clothes to later introduce surreptitiously to New Granada; even clandestine arrivals to hidden coves to unload said contraband. Any of these things could have happened. And because all of these things happened with some regularity, customs officers could not simply dismiss them. Neither can historians combing through the archives today.

In the absence of further records documenting its arrival to other ports between January 10 and April 3 (or between May 29 and June 25), the Santiago’s itinerary remains murky. Its maritime path for the second half of 1793, given that it involved sailing to Sabanilla—a hidden, yet well known, cove frequented by smugglers—features an equally murky space between.

What are historians to do when facing these gaps? Fleeing them to avoid the dreaded (by some, not me) speculation is definitely one path. Embracing them and working to suggest an account that is simultaneously speculative and persuasive seems more enticing.

Contemporary reports abound with complaints about unauthorized travels and testimonies describing the tricks small vessels performed to bypass regulations. French traveler François Depons, writing from Venezuela, described the practice by which Spanish vessels sailing from Neogranadan and Venezuelan ports in 1801 claimed to be sailing to Guadeloupe, when in fact they were headed for British islands like Jamaica, Trinidad, and Curaçao (in 1801 Curaçao was under British control). Similarly, William Walton described how, during the Anglo-Spanish War of 1796-1808, “many Spanish vessels cleared out for Guadeloupe, Martinique, and St. Domingo, then in possession of their allies, and when they returned, produced false clearances and fabricated papers” to cover their actual trips to British islands. Taking advantage of the permissions granted by all imperial powers to trade with neutrals, James Stephen denounced, merchants of all nations were pursuing “a war in disguise” characterized by the fraudulent use of neutral flags to undertake trade with war enemies. The schemes, most times, involved declaring to sail to a port and then proceeding to a different one. This practice warns against taking shipping returns at face value.

Like these foreign observers, local merchants also doubted the advisability of trusting shipping returns. Prominent Cartagena merchant José Ignacio de Pombo, for instance, denounced the contraband transported under the cover of the legal trade in slaves as well as the ways in which small vessels abused permits granted to trade with foreign neutrals. In his opinion, trade with foreigners not only favored contraband but also set a negative precedent and constituted “an addiction, difficult to cure after acquired.” Provincial authorities in Cartagena, Santa Marta, and Portobelo shared Pombo’s concerns. Manuel Hernández, the Spanish crown’s treasurer at Portobelo decried the practice some vessels legally trading with Jamaica pursued: they added stopovers in hidden coves like Sabanilla, and Bahía Honda before entering their official ports of destination. Sabanilla, as ship captain Domingo Negrón witnessed after his schooner, the Concepción, fell prey to a British ship, was a dynamic hidden port, which Spanish vessels legally sailing from Jamaica to Cartagena frequently entered to unload illegal merchandise before officially entering Cartagena with their legal cargo. Bahía Honda, which Spanish authorities considered a marvelous bay “capable of harboring the biggest fleet,” was—unfortunately for Spanish purposes—“only useful to foreign… ships” that used it “to introduce their goods… and take away the palo del Brasil, pearls, cottons, and gold from this province” of Riohacha.

Even when captured in flagrante, smugglers and sailors facing charges of piracy could come up with alibis to save themselves from jail or execution. Claiming that they had entered a forbidden port because their ships were sinking (suspicious Spanish authorities called these arrivals arribadas maliciosas) or that the “winds and currents” had deviated them from their stated courses, many sailors ended up giving judicial declarations in ports where, according to their navigation documents, they were not scheduled to stop. The archival bundles containing these declarations stand as visible counterparts to the invisible files never created by the many ships that fraudulently—either without being noticed by colonial authorities or with their complicity—entered a forbidden port before continuing their navigation to the scheduled port.

Let’s get back to the Santiago to imagine a possible pathway to explain its space between. Two intervals between recorded departures from and arrivals to Cartagena stand out as particularly intriguing: the 83 days between January 10 and April 3 and the 71 days between July 12 and September 21 (maps 2a and 2c). Two months (almost three in the first case) at sea is an awful lot of time for direct Cartagena-Riohacha-Kingston-Cartagena and Cartagena-Sabanilla-Kingston-Cartagena trips. In the first case, the Santiago’s arrival record contains information that makes it possible to believe that its actual trip included illicit transactions in the hidden coves of New Granada’s Caribbean coastline.

Upon entering Cartagena, the Santiago declared “3 bozales” (African slaves) among its cargo. While selling slaves imported from foreign colonies was legal, having only 3 slaves for sale seems hardly a wise business decision. Given the abundance of voices that claimed that “the ships that sailed [to foreign colonies] to look for slaves, brought back contraband goods,” it seems (highly) plausible that the Santiago took part in this illegal trade, many times consisting of clothes. An undeclared stopover in Sabanilla, one of the most frequented hidden coves, to unload said clothes could have accounted for a portion of the 83 days it supposedly spent sailing to Riohacha, Kingston, and back to Cartagena. If the contraband goods included weapons—another item frequently present in reports, denunciations, and seizures—it also makes sense to imagine a potential stopover in Bahía Honda, where the Wayuu were always ready to buy British weapons. Adding these two hidden stopovers still allows time for the winds and currents to have played a role in the Santiago’s journey between its January 10 departure from Cartagena and its April 3 return.

The second long unaccounted interval—between July 12 and September 21—raises similar questions regarding the business skills of the Santiago’s owners and captains. If shipping returns are to be trusted (and it seems, in this case, they should not), the Santiago sailed to Sabanilla “to get palo mora [a dyewood] for sale in Jamaica.” With its cargo of palo mora, it proceeded from Sabanilla to Kingston, sold the palo mora, and then returned to Cartagena “in ballast.” This trip took the Santiago 71 days. Both the duration and the cargo (or lack thereof) make this straightforward trip unlikely. While palo mora was certainly a valuable commodity, it is hard to believe that the only commercial transaction the Santiago undertook during its 71 days of navigation was the selling of palo mora in Jamaica. It simply does not make business sense. In this case, it appears that the Santiago’s navigational trajectory included much more than the shipping returns show. Before entering Cartagena in ballast, the Santiago may have visited Sabanilla or another hidden cove to unload contraband goods obtained in Jamaica. The unlikelihood of a two-month-long Cartagena-Sabanilla-Kingston-Cartagena trip that only involved obtaining palo mora in Sabanilla to sell in Kingston simply calls for other explanations. In the absence of hard evidence, the Santiago’s trip requires speculation.

While shipping returns do not allow us to fill the Santiago’s space between, properly contextualized, they can help us understand its possibilities. Knowing exactly what path the Santiago traversed is impossible. Concluding that its navigational trajectory between January 10 and April 3 (and then between July 12 and September 21) was much more truculent than Cartagena’s port records suggest, seems in this case to be a safe bet.

Using shipping returns to reconstruct the navigational trajectories of Caribbean schooners offers historians a way to imagine alternative paths that deviate from the official ones delineated in books of arrivals and departures. Despite their fragmentary information, shipping returns remain the key source to study maritime networks in the Age of Sail. Reading them with an awareness of their limits helps us understand the mobile world sailors inhabited.

Mobility and mobile lives help us see the world in a different way. Instead of a world of hard borders and fixed geographic units, a focus on mobility brings to life a world of connections invisible to the eyes trained to see through the lens of political geographies. In the world of the Age of Revolutions—the world I inhabit in my research—focusing on mobility allows us to demolish the fiction of “imperial self-sufficiency” created by an excessive emphasis on imperial political geographies as units of analysis. Mobility and mobile lives also pose great challenges and make us aware of the many possible paths mobile subjects could have taken. Following ships as they cut across political boundaries makes these potential paths visible. It opens up the possibilities of the space between.

Maps created by Ernesto Bassi