How Victorian London Almost Ended Up with a Roman Sewer

Edwin Chadwick was not a man especially concerned with the past. A staunch Utilitarian social reformer and friend of John Stuart Mill, Chadwick used statistics to show that the poor faced disproportionate amounts of death and disease in England’s booming industrial cities, and that the reason for this was environmental. As the Commissioner of the brand new General Board of Health, created in 1849, Chadwick became a crusader for a new conception of sanitation—one that drew on ancient Roman precedents even as it looked forward to a new vision of urban modernity.

“All smell is disease,” Chadwick famously proclaimed in front of Parliament in 1846. He was forward-thinking in terms of the social determinants of health, but never questioned the prevailing understanding of disease causation: like other educated Englishmen, Chadwick was convinced that all disease was caused by miasma, or polluted air. The centerpiece of Chadwick’s vision for a modernized, healthy London was therefore a complete reconstruction of the city’s centuries-old sewer system, whose porous brick walls and lack of drainage fostered terrible smells that wafted up to the city above.

Using plans drawn up by the engineer John Roe, Chadwick replaced several old brick sewers with round earthenware pipes that emptied into the Thames. These pipes were installed on a gradient so that sewage would flow out of the city rather than festering underground. In a report to Parliament regarding the status of these trials, the forward-thinking Chadwick made an appeal to antiquity:

When upon the observation of the evil effects and the expense of permeable brick drains, I proposed the substitution of tubular earthenware drains, I was unaware that the simple expedient had ever been tried; but Mr. [Edward] Cresy traced out the tubular earthenware drains as systematically laid down in the colosseum at Rome.

He continued:

A friend at Zurich has forwarded to me a specimen of an earthenware pipe laid down by the Romans probably two thousand years ago, and which has worked until recent times under five hundred feet of pressure. Vitruvius points out the evils of lead and metal pipes for the distribution of water, and the advantages of earthenware pipes as substitutes. Miss [Harriet] Martineau recently found the remains of earthenware pipes laid down for the distribution of water through the ancient city of Petra. The remains of water-closets, which are thought to be an English invention, were found at Pompeii.

This same Edwin Chadwick later dismissed the study of history as “one great field of cram, of reliance on memory, and of dodging.” Still, the sources and material he cites above betray him as something of an archaeology buff, familiar with trends in the rapidly maturing field. Chadwick used these few bits of information to manufacture a new vision of the past, one in line with his own political beliefs. He was one of the first modern politicians to discover the power of cherry-picked historical anecdotes. And he did so by digging deep into the history of something few of us want to think about: the sewer.

At the dawn of the nineteenth century educated Englishmen were certainly familiar with the ancient Romans. But they knew them as abstractions, filtered through the tortuous Latin of Tacitus and Vergil’s heroic verse, or the high political drama of Gibbon’s Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire.

By the 1840s, however, the study of the ancient world was undergoing a revolution.

No longer focusing exclusively on great works of art, curiosities, and the romanticism of ruins, European scholars began to take a more painstaking approach to excavating. Archaeology suggested a host of new questions. How did ancient people build their impressive monuments in the first place? How and when did their cities grow? How did the Romans manage the physical requirements of their daily lives, like acquiring water and disposing of waste? By the end of the century, thanks to men like William Cunnington, Christian Jürgensen Thomsen, and Augustus Pitt Rivers, archaeology had become a recognized scientific field with its own jargon and formal methodologies.

1849, the year Chadwick seems to have discovered the utility of archaeology for his own project, falls right in the middle of this transformation from antiquarianism to archaeology. There had been just enough news of the engineering marvels of Roman civilization published to capture the collective European imagination, but not enough so that Chadwick could refer to an authority on Roman sewers. Instead, he had to piece together his own picture of ancient sanitary engineering using a hodgepodge of sources.

The Mr. Cresy Chadwick refers to is the architect Edward Cresy, who in 1821 along with his colleague George Ledwell Taylor published The Architectural Antiquities of Rome. The book included the first architectural plans of a number of Roman monuments, including the Colosseum. Unlike Giovanni Battista Piranesi’s romantic etchings of Roman ruins from the previous century, Taylor and Cresy’s plans were drafted with an architect’s eye for precision. These plans were detailed enough to include the drainage system in plain black and white, neatly labeled.

The other contemporary writer Chadwick cites, Harriet Martineau, was, like Chadwick, a pioneering social reformer involved in Whig politics. Also like Chadwick, she was not an archaeologist, antiquarian, or historian. Instead, her knowledge of the drainage systems of ancient Petra, a Nabataean-Roman trading city in modern Jordan, came from a sightseeing trip she took with friends on a whim in 1846. Martineau published her notes from this trip in 1848 in a massive multi-volume book titled Eastern Life, Present and Past.

Her description of Petra’s water system in this book is a single sentence long: “A conduit runs along [the main street], and a little above, the wayside—a channel hollowed in the rock: and in parts there are, at the height of thirty feet, earthen pipes for the conduit of water.” In 1848 and 1849, Martineau gave a series of public lectures on a wide range of topics including history and sanitation; perhaps Chadwick heard about the Petra pipes at one of these. Petra was not formally excavated until the 1890s, so traveler stories like Martineau’s were the only way an interested party in London could learn about the site, short of going there himself.

For other evidence to support his vision of Roman rational sanitation, Chadwick cites the excavations of Pompeii. Ongoing since 1748 and more recently a popular tourist spot, Pompeii was in 1836 the subject of a two-volume publication of the Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge, a Whiggish project for public education. Chadwick mentions the first century BC architectural writer Vitruvius, who wrote (among many other things) on the best kind of plumbing. Intriguingly, he also mentions a recovered specimen of Roman terra cotta pipe from the Roman city of Turicum (present-day Zurich). This is the only piece of Roman hydraulic engineering that Chadwick seems to have seen with his own eyes.

Chadwick does not reveal the name or the occupation of his Swiss friend: was he a member of the growing class of scientific archaeologists? A landowner who discovered the pipe on his estate during construction? Or an antiquities collector? Regardless of its origin, the pipe was to Chadwick physical proof of the brilliance of the Romans who, he had just discovered, shared his opinion on the best type of sewage removal system. It was to become briefly famous in Anglophone sanitarian circles.

In January 1850, the Edinburgh Review, a Whig-leaning periodical for which both Chadwick and Harriet Martineau had written, picked up and augmented Chadwick’s small body of evidence for Roman rational sanitation in a review article on recent developments in public health:

With them nothing seems to have been deemed ‘common or unclean’ that could protect the public health. We find Pliny writing to Trajan about a fetid stream passing through Amastris, as if it were an affair of State. The cloacae of the Tarquins are still among the architectural wonders of the world. The censors, ediles, and curators, who at different periods had charge of the buildings, and of the apparatus for the removal of impurities, were invested with great powers for the execution of their functions, and derived a corresponding dignity from them.

The Edinburgh Review was targeted at people much like Chadwick and Martineau: educated, well-off, and interested in social reform. They were perennially concerned with the lot of the poor and, more recently, the public health. The review quoted above goes on to detail recent developments, especially the progress of the sewer system, and the containment of cholera in the city. The above passage does something radical: it places the modernizing program of the sanitarians within a historical context, giving it an august genealogy stretching back to the early days of Western civilization.

This is a much more political—and radical—point than the technical-minded Chadwick ever made, and it relied on the convergence of two things: first, the classical education the Review’s readers would have received, and second, the cutting-edge, if hodgepodge, archaeological research collected by Chadwick. The first stirred up a sense of historical importance and imagination. The second drove home the point that modern London could literally rebuild itself in the model of ancient Rome, transforming itself from a pestilential cesspit into a paragon of public health.

As carefully researched as Chadwick’s plan was, it stalled in Parliament. Earthenware pipes were a hard sell to architects and contractors, who were used to building cheaper brick sewage systems in new construction. Even more difficult was convincing local authorities to require the replacement of existing drainage systems. Chadwick managed to organize limited trials in the suburban neighborhoods of Richmond and Sydenham, but the tangle of old buildings in central London presented more of a problem.

The biggest roadblock was securing funds: tearing apart and rebuilding central London would require a significant investment from the government. Chadwick proved not much of a politician. He argued his case with painstaking surveys of the sanitary conditions and outflow volumes of London neighborhoods, and equally exacting trial runs with differently sized round pipes, all of which he dutifully reported back to Parliament. As Chadwick’s biographer R.A. Lewis put it, this campaign for a new sewer “was dullness unrelieved.”

Chadwick did eventually bring about the legislation that funded a new sewer system for London, but only in an indirect and unfortunate way. The one aspect of his program that Chadwick had been able to enforce was the elimination of private cesspools, which he had pushed through in the late 1840s. All residences in the metropolitan area now had to be connected to the existing sewers, which emptied into the Thames. This was perhaps Chadwick’s greatest misstep: he moved the bulk of human waste out from under houses and into public space. In summer the smell was prodigious. Worse still was that much of the city’s drinking water still came from the Thames, downstream of the sewer outflow.

In 1848, Punch criticized the foul and worsening condition of Thames water with a cartoon of the Thames personified as a grizzled old man trying in vain to clean himself up. The cartoon was accompanied by a poem that began:

Filthy river, filthy river,

Foul from London to the Nore,

What art thou but one vast gutter,

One tremendous common shore?

All beside thy sludgy waters,

All beside thy reeking ooze,

Christian folks inhale mephitis,

Which thy bubbly bosom brews.

All her foul abominations

Into thee the City throws;

These pollutions, ever churning,

To and fro thy current flows.

And from thee is brew’d our porter -

Thee, thou guilty, puddle, sink!

Thou, vile cesspool, art the liquour

Whence is made the beer we drink!

Chadwick had recognized the poor condition of the water and in fact had campaigned for a reorganization of London’s water supply as part of his sanitation program, but was unsuccessful because of a combination of his growing political unpopularity and vehement opposition from the private water companies that supplied the city. In the meantime London bustled around a water source that at best stank, and at worst circulated pathogens including cholera from privy to water pump and back again.

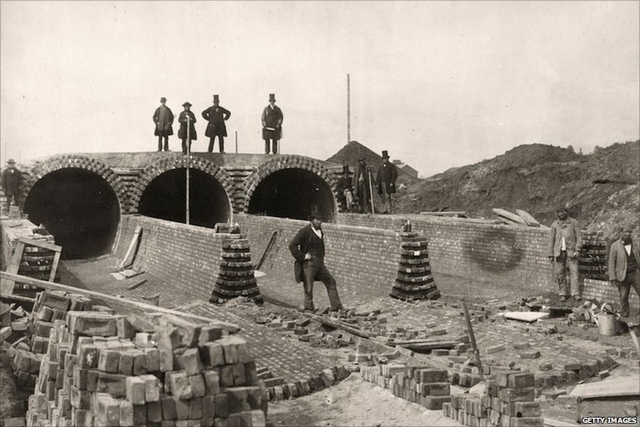

What finally convinced Parliament to loosen its purse strings and fund a new, state of the art sewer system was the Great Stink of 1858, during which the stench of the sewage-filled Thames infiltrated Westminster Palace. Unable to concentrate on normal business due to the smell, the House of Commons pushed through funding for the sewers and began searching for an acceptable proposal. A plan by Joseph Bazalgette, chief engineer of the Metropolitan Board of Works, was accepted the next year.

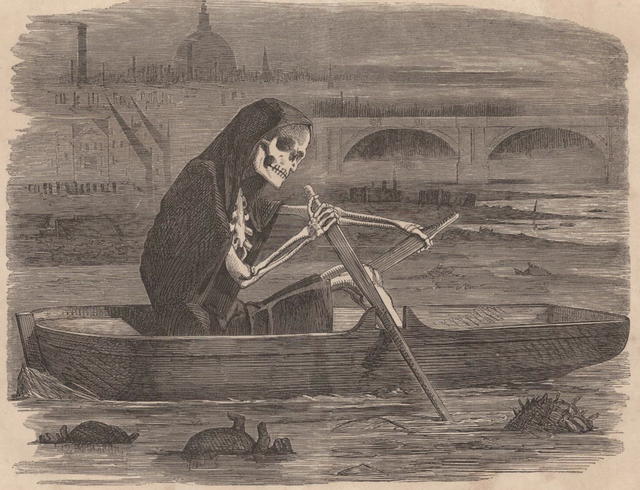

Death portrayed as a highwayman roaming the Thames during the Great Stink (Punch, July, 1858). Wikimedia Commons

While Bazalgette relied heavily on Chadwick’s sanitary research for the specifics of his plan, his sewers ferried waste far downstream of city limits by way of pumping stations and newly invented “deodorizing” intercepting sewers. Bazalgette’s pipes were also much larger than the ones Chadwick proposed: looking to the future, he accounted for a continued boom in London’s population.

The sewers themselves were encased in the monumental embankments that still line the Thames today. At the beginning of its construction in the early 1860s, the Observer called London’s new sewer “the most extensive and wonderful work of modern times.” Though the fact went unremarked, Bazalgette’s sewer also far surpassed the Roman one Chadwick so admired. It was larger in capacity and used new techniques to minimize smell and leakage. Although Pliny the Elder named Rome’s sewers and drains as “the most noteworthy things of all” among the Roman Empire’s accomplishments, they were physically and technologically dwarfed by Bazalgette’s system.

The construction of London’s new sewers happened just as European scientists were delivering death blows to the old miasma paradigm of disease causation that Chadwick had so believed in. In 1854, John Snow famously proved that cholera was transmitted not by smell but by contaminated water; between 1860 and 1864 Louis Pasteur collected evidence connecting microscopic pathogens to the spread of disease. The Romans, it turned out, were not the final authority on what made a person or city healthy.

Just as scientists of the late nineteenth century turned their backs on ancient disease theory, British public health leaders ceased holding Rome up as a paradigm of urban sanitation in Parliament and in public outreach. The reason was simple: in the time between Chadwick’s first call for a renovation of the sewers and the completion of Bazalgette’s system, European health science had surpassed Roman achievement. Like medicine, public health now turned to the future.