Atomic Anxiety and the Tooth Fairy: Citizen Science in the Midcentury Midwest

How the St. Louis Baby Tooth Study reconciled the domestic ritual of childhood tooth loss with the geopolitics of nuclear annihilation.

Ava was getting desperate. Her latest baby tooth to come loose was hanging on with uncharacteristic vigor. No matter how she worked at it, there it was—wiggling in her jaw every time she ate, drank or talked. She had been waiting for her next loose tooth ever since her homeroom teacher had announced Operation Tooth in class. Other kids already had their buttons and tooth club membership cards. Ava was tired of waiting.

Ava looped a string around the base of the tooth and tied the other end to a doorknob. She braced herself in a chair, cocked her head back, opened wide, and slammed the door. The tooth clattered on the linoleum. She couldn’t see it at first—it blended in with the white speckles on the blue tile—but she scanned the floor until she found a tiny dot of blood. Her tooth. She picked it up, wrapped it in tissue, and prepared her letter. She was going to help scientists, and everyone would know it because the scientists were going to send her a bright red button inscribed with the following message:

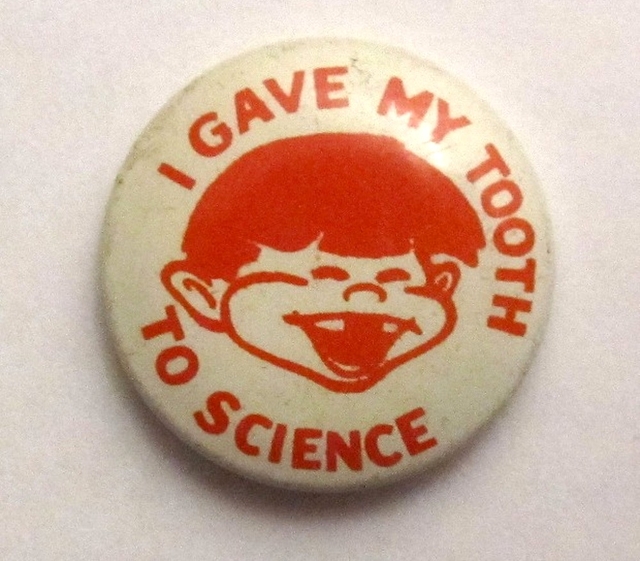

I GAVE MY TOOTH TO SCIENCE.

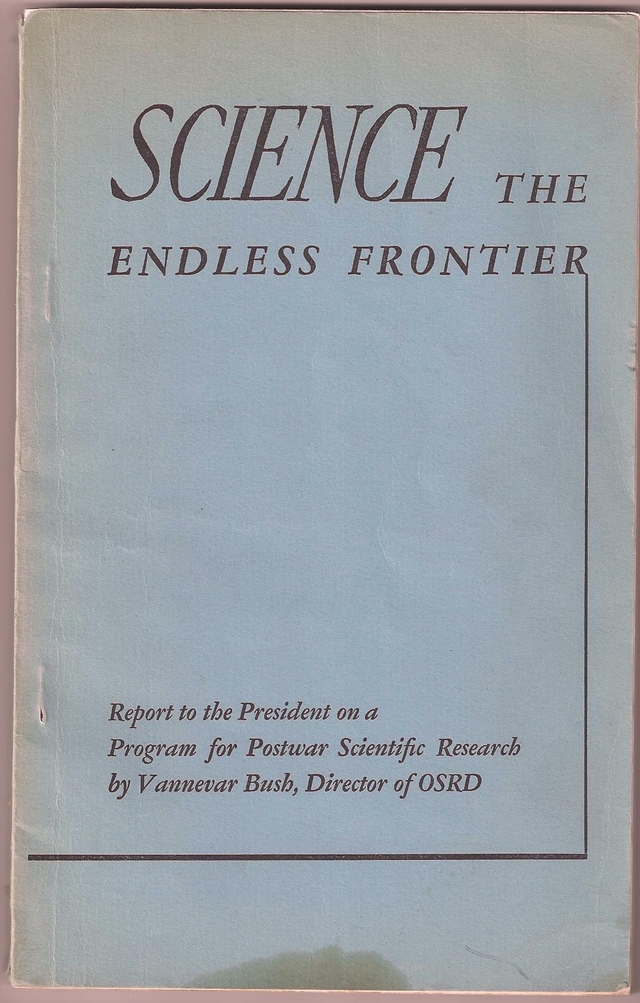

Button pins like this one were sent to children in recognition of their donation of a tooth. St. Louis Post-Dispatch August 1, 2013

For a few days in January of 2014, I drove each morning in bitter cold from my mother’s house in the St. Louis suburbs to the state historical archive at the University of Missouri-St. Louis. A few months earlier, an archivist friend had mentioned over lunch that she had a connection to my hometown—in fact her first job as an archivist was in St. Louis, organizing the papers from a midcentury study of radioactivity in children’s teeth. I had been unable to shake the story, and found myself up late at night reading about nuclear weapons testing, or daydreaming during work about purity and milk, innocence and poison, the movement of invisible contamination. A follow-up with my archivist friend revealed that the archive contained letters from children—to scientists, and to the tooth fairy.

The story unfolded against my expectations. I went to the archive expecting cute letters from children and poignant missives from parents concerned about their kids’ exposure to radiation. I found these, to be sure—at the end of each day in the archives I felt exhausted from the weight of the letters’ polite Midwestern formality tinged with anxiety. The story I didn’t expect, though, had much higher stakes.

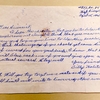

In the postwar United States, scientific progress dominated national conversations. Vannevar Bush’s influential report to President Roosevelt, “Science: The Endless Frontier,” set the terms of this conversation in 1945. The report, which international historian Odd Arne Westad calls “the classic statement of technology as power in the postwar world,” promised rewards to every sector of society in return for state investment in science:

Advances in science when put to practical use mean more jobs, higher wages, shorter hours, more abundant crops, more leisure for recreation, for study, for learning how to live without the deadening drudgery which has been the burden of the common man for ages past. Advances in science will also bring higher standards of living, will lead to the prevention or cure of diseases, will promote conservation of our limited national resources, and will assure means of defense against aggression. But to achieve these objectives—to secure a high level of employment, to maintain a position of world leadership—the flow of new scientific knowledge must be both continuous and substantial.

Bush’s promises obscured the clash between nationalism and science that came to the fore as the euphoria of V-Day gave way to the Cold War with the Soviet Union. By the late 1950s, any scientist who questioned the United States’ atomic test detonations risked meeting the same fate as J. Robert Oppenheimer, disgraced and dismissed as a Communist sympathizer.

Yet the scientists of the Greater St. Louis Committee for Nuclear Information not only expressed their misgivings, but also proved the validity of their concerns with a citizen science project carried out on a massive scale. The study collected more than 250,000 baby teeth from the children of St. Louis city and county and analyzed them for traces of radioactivity. This effort to understand and inform the public about the effects of radioactive fallout from above-ground atomic weapons testing ultimately persuaded President John F. Kennedy to sign the Limited Nuclear Test Ban Treaty in 1963. Tiny teeth, it turned out, could speak louder than bombs.

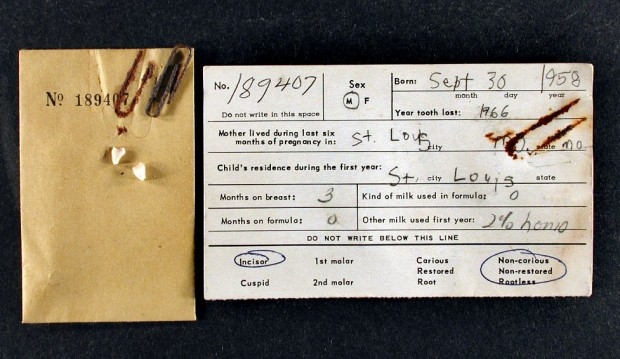

A survey card from the St. Louis Baby Tooth Survey. St. Louis Post Dispatach / University of Washington at St. Louis

In August of 1958, Nature published a brief article by Danish biochemist Herman M. Kalckar. Though scarcely more than a page long, the article’s innovative thesis sparked a vast research project that defied official public safety claims with evidence taken from the mouths of St. Louis’s child population. Scientists suspected that radiation from the above-ground atomic weapons tests taking place from 1945 onward could pose a significant health risk to the populace, but no one knew how much radiation human bodies were absorbing. Atomic weapons detonations released the radioactive isotopes Strontium-90 and Cesium-137 into the environment as explosion debris. These were entirely new substances that had not existed until the advent of nuclear weapons testing. Some of the debris contaminated with these previously unknown isotopes fell to earth quickly, but the rest remained in the atmosphere, mixed with water molecules, and eventually fell to earth as rain. It then passed into the food chain and subsequently into the body. Cesium-137 (CS-137) accumulated uniformly across bodily tissues due to its chemical similarity to salt. Strontium-90 (SR-90), however, was similar to calcium and thus accumulated mainly in calcium-rich areas, posing the potential for cancer in bone and surrounding tissues as it decayed over its twenty-nine-year half-life.

Kalckar opened his article with a disclaimer and a refusal: “Without expressing here any opinion concerning atomic weapons test programmes, I wish to suggest a scientific study which would at the same time have educational values in its practical demonstration of the peacetime value of atomic research.” Not all of Kalckar’s academic colleagues were so reticent. To the contrary, physicists and other scientists had begun voicing grave concerns about the ill effects of fallout from atomic weapons testing programs on public health.

The article’s argument was simple. Geiger counters could measure radioactivity in food, but tracking its absorption into and passage through the human body was a trickier matter. How to measure the levels of radiation absorbed by the human body? Bone samples were one avenue by which accumulation in the body could be measured. However, the limited samples of bone available from autopsied adults provided a small and erratic body of data.

To avoid these problems, Kalckar proposed turning to a different source of samples: children’s baby teeth. Near-term prenatal incisor teeth (in other words, children’s front baby teeth or “milk teeth”) took up high levels of radioisotopes during their formation, yet renewed their cells at a far slower rate than bone. Therefore, baby teeth could provide a stable snapshot of radiation absorbed by human bodies in a given geographic area around the time of a child’s birth. Since children tend to shed incisor teeth around the age of seven, teeth being shed in 1958 would reflect the levels of environmental radiation absorbed by unborn children around 1951.

The first atomic bomb test, codenamed Trinity, took place in 1945. The United States was the sole nation to wield the bomb until 1949, when the Soviet Union performed its first atomic test detonation. The number of tests increased year by year as the 1950s unfolded and the Cold War intensified, with both the United States and the Soviet Union attempting to exceed the other in demonstrations of nuclear might. While US atomic weapons testing initially took place in the Pacific Islands, cost and timing considerations drove the decision to begin testing within the United States in 1951. Testing continued in the Pacific, including the detonation of hydrogen bombs too powerful to test closer to home.

The US’s 1954 test Castle Bravo (the second and most powerful American hydrogen bomb test) took place at Bikini Atoll, and it was more than eight hundred and forty five times as powerful as the Trinity test. Due to a misunderstanding of the reaction between the uranium and hydrogen elements of the device, the test released almost three times the expected destructive power—and radioactive fallout—its creators had anticipated. The unanticipated volume of fallout from the detonation poisoned fish and Marshall Islanders alike, and caused an international uproar over the toxic aftereffects of atomic testing.

The atomic testing of the 1950s raised unsettling questions. If the detonations in the South Pacific were sickening Marshallese people and killing Japanese fish stocks, were they also exerting milder effects as far away as the United States? For that matter, how was the continued testing of atomic weapons in Nevada affecting food supplies in the United States? In 1957 alone, the United States government detonated twenty-nine atomic weapons in the Nevada desert.

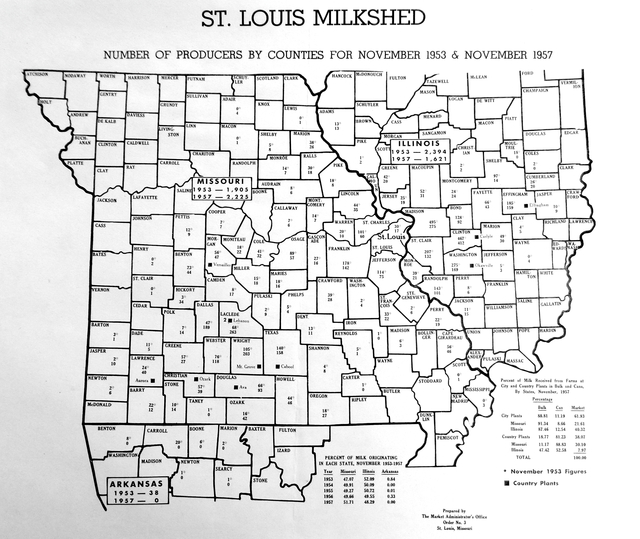

The presence of the new isotopes prompted concerns about food safety. Because of its high calcium content, the milk of cows grazing in fields contaminated by fallout from atomic bomb tests was a likely site for concentrated accumulations of radioisotopes. Milk SR-90 levels had risen in April of 1957. In response, the U.S. Public Health Service initiated a pilot study to test milk for SR-90 and CS-137. Milk was already the focus of contamination concerns; further, milk was particularly well suited for a survey of contamination levels because it was produced across the nation and year round, providing a source of data independent of seasonal rhythms and local growing seasons. The study drew samples from “milksheds” in five cities: New York, Cincinnati, Sacramento, Salt Lake City, and St. Louis. In 1958, the Health Service reported its results.

St. Louis reported the highest levels of SR-90 in its milk supplies.

Milk supplies flowed to St. Louis from across the bi-state area, as this map of milk producers shows. State Historical Society of Missouri, University of Missouri-St. Louis

Still, the Public Health Service framed this level as being well below the suggested threshold level of lifetime exposure to SR-90. A lifetime of consuming such milk, it assured, would only expose a person to about one-fourth of the safe lifetime exposure level. The reassurances implicit in the Public Health Service’s claims rested on one key assumption: a nonlinear threshold model of SR-90 exposure. Exposure to 80 micro-curies or less of SR-90, it suggested, was safe. But many physicists rejected the nonlinear, threshold model of radiation exposure, objecting that the scientific evidence behind such a model was flimsy and unreliable. They feared that the threshold model espoused by the authorities would lull the public into a false sense of certainty when, in fact, so much about the physical effects of exposure to radioactive fallout remained unknown.

The Public Health Service was right to be concerned. A linear risk model with no minimum threshold is now widely accepted as the consensus model of radiation exposure on human health.

Debate and uncertainty over conflicting models of radiation exposure and its health effects entered the public consciousness when Adlai Stevenson made it a key point in his 1956 bid for the presidency—charging, for example, that the U.S. Government had known about SR-90 contamination in milk as far back as 1954 but had failed to inform the public. But it was physicist Linus Pauling’s public talks at universities that rallied thousands of scientists to publicly speak out against the ongoing testing. Strontium-90 had not existed before the atomic bomb, and scientists were unsure of its effects on public health. It was “a new hazard to the human race,” Pauling urged, “a new hazard to the health of people—and scientists need to talk about it.” After a particularly impassioned speech in 1957 at St. Louis’s Washington University, Pauling, together with physicist Edward Condon and biologist Barry Commoner (both faculty members at Washington University) drafted what would become known as the Pauling Petition. The petition, which called for a halt to atomic weapons testing, garnered signatures from 9,235 scientists by the time Pauling presented it to the United Nations in January of 1958.

A month after the drafting of the Pauling Petition at Washington University, Commoner wrote to Pauling:

We are about to try to organize a local group in St. Louis which might be called something like The Citizens Committee for Atomic Information. The idea would be to provide a means for getting the facts about fallout—and probably about the consequences of nuclear warfare—before the public so that people can decide for themselves what our policy on these matters should be.

This group, the Greater St. Louis Citizens’ Committee for Nuclear Information (CNI), brought together physics, biology and dentistry faculty from Washington University and Saint Louis University with laypeople (many of them volunteers from civic and social organizations such as the League of Women Voters) in its membership. Members wrote essays for publication in general-interest magazines, stuffed envelopes, and gave talks to local Kiwanis Clubs and other interested members of the public about the basics of atomic science, explaining what we knew—what isotopes are, for example—and what we didn’t know—most pressingly, how radioactive fallout from nuclear testing affects the body. Members also took part in what turned out to be more than a decade of scientific data collection for a project inspired by Herman Kalckar’s short article on teeth as sources of data on radioisotope absorption levels.

Kalckar’s article established a method by which researchers could chart the levels of radiation absorbed by human bodies. Yet establishing baseline exposure levels for the years prior to massive multiple test detonations would require immediate action. In 1951, only about 24 nuclear test detonations had taken place, many of them relatively small compared to the kiloton or megaton levels of tests between 1952 and 1958. If scientists acted quickly, they could collect the data inscribed in deciduous teeth during the period preceding the 1952 and 1954 detonations of hydrogen bombs. The evidence of those baseline levels of absorbed radiation from the early years of testing was all around, in the mouths of children. It slept in their jaws, was nestled under their pillows and thrown away or stashed in drawers after being exchanged for fifty cents from the “Good Fairy.”

CNI initiated the Baby Tooth Survey in December of 1958 with a grant from the United States Public Health Service (later funding came from subsequent Public Health Service grants, along with funds from the Leukemia Guild of Missouri and Illinois.) Louise Reiss, an internist at the St. Louis City Health Department, helmed the study, which aimed to collect 50,000 teeth a year from children in the St. Louis area in order to acquire sufficient quantities of tooth material for testing.

Such an ambitious effort required the participation of every school in the St. Louis area and a publicity blitz to match. Reiss met with the superintendents of each school system. She met with dentists, school librarians, YMCA directors, local dental and pharmaceutical professional groups. A 1964 report on the study detailed the extraordinary support Reiss won from the community:

During the weeks of the semi-annual Tooth Round-ups, public service time is given generously by radio and television stations to publicize the needs of the Survey. Mayor Raymond Tucker has proclaimed Tooth Survey Week. Last December the Veiled Prophet queen, St. Louis’ traditional reigning beauty, celebrated the Survey’s fifth birthday with a party at Children’s Hospital. A large model of a tooth (with a child inside) gives out forms in department stores. And, most important, dentists are reminded by letter and at conventions how helpful it will be if they make the forms available in their offices. So well known has BTS become that letters from children, addressed simply “Tooth Fairy, St. Louis,” reach their destination at the CNI office.

It was a coincidence the city that reported the highest measured levels of SR-90 milk contamination in the nation hosted the Baby Tooth Survey, but the high levels of contamination may have lent urgency to the effort and prompted higher levels of parental participation in the Baby Tooth Survey. As a New York Times article in July of 1960 noted, ”St. Louis area residents have an occasional twinge of nervousness at their unwanted position at the top of the list.”

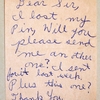

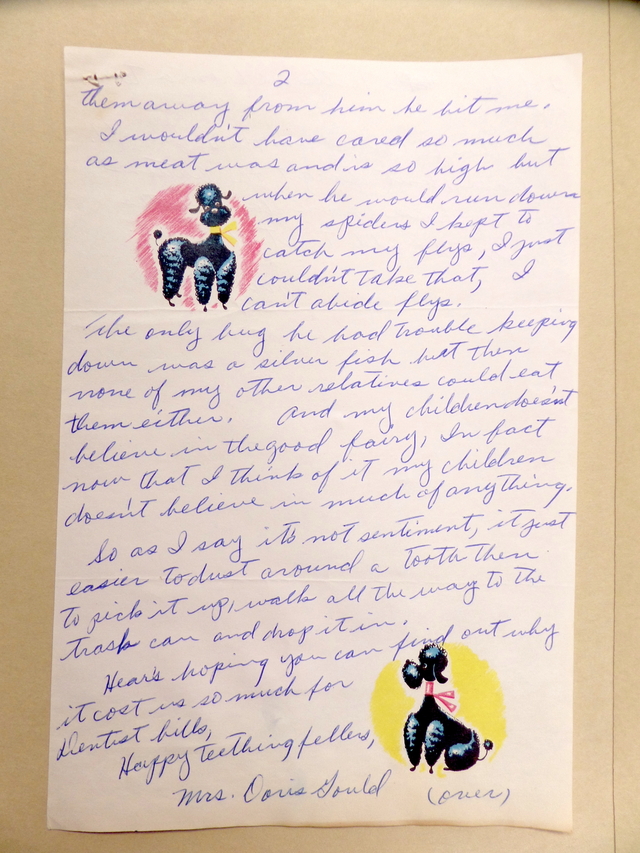

Both kids and parents sent letters to CNI. Children often mentioned the fifty cents they were giving up to help science, and even in some cases requested repayment: “that will be fifty cents, keep the teeth,” wrote one. A childhood fascination with the abstraction of science (reminiscent of Vannevar Bush’s postwar report) abounds: “I always loved science and things of the sort,” confided one young girl. “I hope you are successful in what you are trying to do for science and people.” Another boy praised the scientists for their bravery and selflessness, declaring that God would give them “an eternal reward” for their good deeds (one wonders if perhaps a classroom lesson on the Curies’ death from exposure to radium prompted him to imagine the CNI scientists’ work as a suicide mission). Many addressed their notes to the Tooth Fairy, and one kid began simply “Dear Science.”

Adults in St. Louis who took part in the study as children recall the lure of the I GAVE MY TOOTH TO SCIENCE buttons sent out to participant children, a visible marker of honor and belonging. Kids’ notes bear this out: “Dear Sir,” one reads, “I lost my pin, will you please send me another one? I sent for it last week. Plus this one? Thank you.”

Letters to CNI from children.

State Historical Society of Missouri, University of Missouri-St. Louis

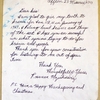

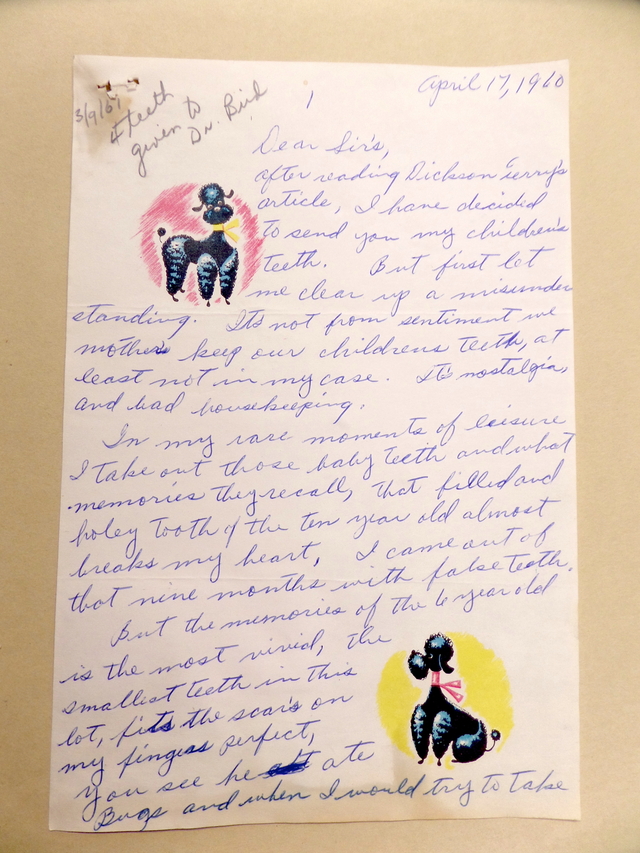

In contrast to the kids’ concerns about button pins and tooth fairy money, parents’ letters are at turns anxious or good-humored. Some letters enquired about possible means of lowering the radiation risk from milk, including a parent whose doctor advised that freezing milk would cut its SR-90 levels in half. Another note asked plaintively, “Please send any results that you may have on the study of strontium 90 content in our children and what it is doing and any available information on St. Louis children.” Despite the gravity of the study, though, many notes have a light, chuckling tone that perhaps helped parents make peace with the study’s dark possibilities. For example, mothers writing to CNI told stories of younger siblings trying to work their teeth loose in exchange for a button, or waiting eagerly on the doorstep for the button to arrive in the mail delivery: “please, hurry, it’s kinda cold out there.” One letter written on stationery festooned with poodles closed with the sign-off, “happy teething, fellers!” The same mother promised in another note, “as fast as the boys knock each others’ teeth out, I will send them to you.”

Letter from Doris Gould to CNI.

State Historical Society of Missouri, University of Missouri-St. Louis

Each tooth was placed in an unsealed, numbered envelope. The tooth information form served as a file card. The file card was numbered, any missing information was obtained via phone, and the tooth-bearing envelope and file card were clipped together and boxed for delivery to a volunteer dentist. The dentist examined each tooth, noting the condition of the root and the presence of cavities and/or fillings. He then sealed the tooth in its envelope and filed it in a box by number.

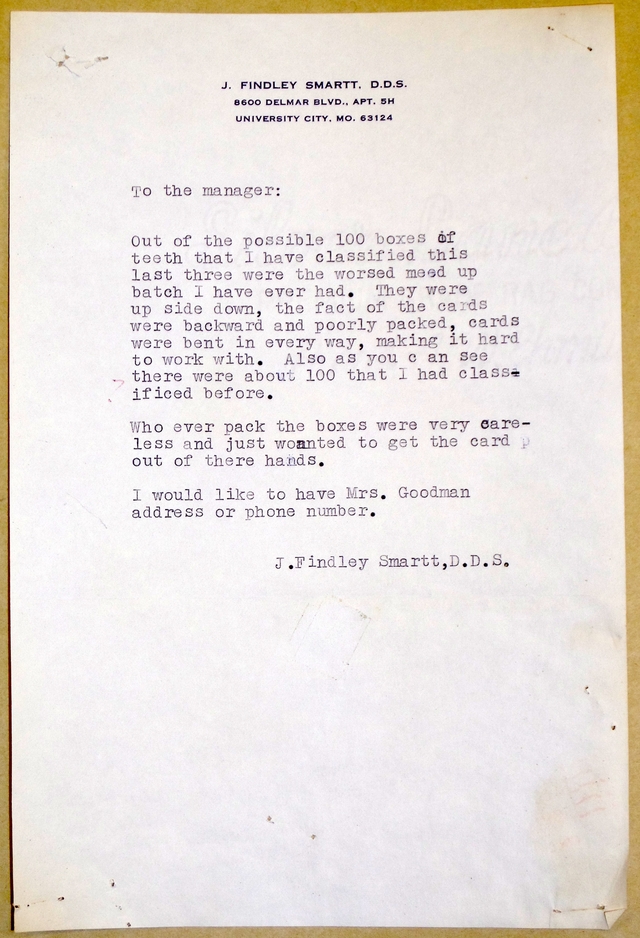

The volunteer workforce produced work of varying quality. In an undated note, dentist J. Findley Smartt of University City fumed, “Out of the possible 100 boxes of teeth that I have classified this last three were the worsed meed up [sic] batch I have ever had. They were up side down, the fact [face?] of the cards were backward and poorly packed, cards were bent in every way, making it hard to work with… Who ever pack the boxes were very careless and just wanted to get the card out of there hands.” Perhaps Dr. Smartt was simply a poor typist, but it’s easy enough to imagine him dashing off this note on his receptionist’s typewriter after hours, and to see in its many typos and extraneous spaces between letters a register of his irritation.

Letter from J. Findley Smartt to CNI. State Historical Society of Missouri, University of Missouri-St. Louis

Once the teeth had been examined, they were returned to the CNI office. The teeth were catalogued by year. Selected samples from each year were collected into pooled sample lots and the remaining samples were sent to storage. The pooled lots were forwarded to Isotopes Incorporated, a commercial laboratory based in Westwood, New Jersey. There the concentration of SR-90 was measured in the Survey teeth, along with additional samples of cow milk, human breast milk, and the bones and teeth of full-term stillborns. Dr. F. Bazan of Isotopes Incorporated then sent test results by mail, and they were incorporated into Reiss’s findings.

Meanwhile, SR-90 levels in the St. Louis milkshed climbed as the 1950s drew to a close. The New York Times reported eighteen and a half micro micro-curies in January of 1959. Twenty-two and a half micro micro-curies in March. Twenty-five micro micro-curies by October.

Louise Reiss published the initial findings from the CNI’s Baby Tooth Survey in November of 1961. The study found that bone and teeth took up SR-90 at the same rate, making teeth a viable substitute for bone samples. Of the teeth studied, SR-90 levels in the incisor teeth of children born in 1951 was dramatically lower than levels for those born in 1954. There was no appreciable difference in SR-90 levels between the teeth of children fed breast milk and those fed cow’s milk during the early years of their lives. These findings reached to the highest levels of American power: in 1963 Reiss’s husband Eric, a medical doctor and Washington University faculty member, related the study’s findings at congressional hearings on the effects of fallout. According to the recollections of Reiss’s son, President John F. Kennedy telephoned Reiss at home to discuss the research and its implications. Shortly after the hearings, Kennedy signed the Partial Nuclear Test Ban Treaty. The Baby Tooth Survey continued until 1970. Data from the study showed that strontium 90 levels in children’s teeth peaked in the mid-1960s, at fifty times the magnitude measured for 1950.

Perhaps one of the reasons Reiss’s paper had such an impact on President Kennedy is that it didn’t fit the prevailing narrative about atomic fallout and its dangers. By 1961, the fallout shelter loomed large in popular culture. Life magazine printed a special issue on fallout shelters in September of that year. A man in a metallic “civilian fallout suit” peered gravely from the cover, his furrowed brow and wide eyes framed in the transparent face-plate of the suit. The issue featured a letter to the public from President Kennedy announcing a civil defense initiative to identify public buildings that could serve as public fallout shelters, label them clearly, and stock them with food, water and medical supplies sufficient for two weeks’ survival. A thirteen page-spread followed, with cutaway views of backyard shelters, basic principles for reducing radiation exposure, and photographs of young families grimly displaying the blankets, radios and board games with which they had stocked their own shelters.

Just two weeks after the issue hit newsstands, the television show The Twilight Zone aired its episode “The Shelter,” in which suburban conviviality quickly devolves into battles over the limited space in a backyard shelter once the bomb sirens sound. That autumn, the Office of Civil Defense distributed more than 20 million copies of “Fallout Protection: What to Know and Do About Nuclear Attack,” a 46-page booklet detailing strategies for surviving the fallout that would accompany an atomic attack. The magazines, informational booklets, television shows, comic books, instructional films, and pop songs of 1961 reflected a consistent narrative in the cultural imagination, a narrative in which fallout from cataclysmic Soviet nuclear strikes drove the population into shelters.

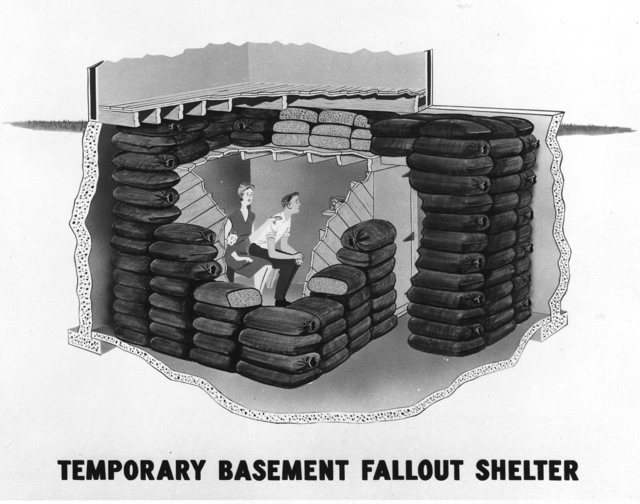

A 1957 Civil Defense rendering of a fallout shelter. “Temporary Basement Fallout Shelter, (artist’s rendition.) - NARA — 542104,” via Wikimedia Commons

The dominant trope of Soviet attack and shelter below ground was sensationally cinematic; nuclear attack fantasies in popular culture still follow the basic formula of tranquil (if banal) routines interrupted by a literal flash and bang that changes lives irreversibly. The power goes out, the radio fails to deliver anything but a canned emergency message, and the survivors inhabit a broken world where the living envy the dead. The results of the Baby Tooth Survey suggested another story, one in which fallout quietly infiltrates foodstuffs and human bodies as day-to-day life rolls on unimpeded. It’s a story that presents atomic danger—and science itself—in completely different terms.

Science, The Endless Frontier offered a vision of science as the source of American military and economic power. The spectacular horror of American nuclear warheads exploding over the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki fixed atomic weaponry as the centerpiece of postwar American science. This was a muscular science, an almost paternal force powerful enough to protect the United States’ geopolitical dominance and provide for every aspect of American lives. Kalckar’s article, and the Baby Tooth Study that it inspired, drew on Bush’s vision of science but also revealed its shortcomings. Kids’ letters to the CNI bear this out. They reflect and sometimes directly address a heroic but abstract concept of science. CNI drew strength from the fantastic possibilities of science in the public imagination with the I GAVE MY TOOTH TO SCIENCE button pins that kids so coveted. Yet the fascination with progress and possibility that infuses the kids’ letters is the same spirit that, when combined with military prerogatives, spurred the ongoing atomic tests that the study sought to question. CNI mobilized that spirit to gain kids’ participation (and their teeth). But it also used the principles and methods of science to reveal the harms that might result from a cavalier sense of mastery over nature.

To paraphrase political theorist Jane Bennett, there was no “away” to which the fallout could go.

Yet the trope of Soviet attack could not account for the insidious rise in SR-90 levels across the country. Popular coverage of the Baby Tooth Study reconciled the mundane, domestic ritual of childhood tooth loss with geopolitics, technological innovation, and scientific discovery by transforming the figure of the Tooth Fairy. A 1960 issue of Woman’s Day magazine, for example, illustrated a short news item about the Committee for Nuclear Information with an image of a tiny, balding, bespectacled scientist with lab coat and wings. He alights from a sleeping child’s bed, grinning smugly at the tooth in his cradled hands. With the image of the tooth fairy as scientist, the child’s lost tooth is transformed from an artifact of innocence to a complex geopolitical resource.

Acknowledgements:

The authors wish to thank Anne R. Kenney; Michael and Jessica Friedlander; Zelli Fischetti, Kenn Thomas, and Nancy McIlvaney at The State Historical Society of Missouri; and Amy Kohout.