Photographing the Guillotine

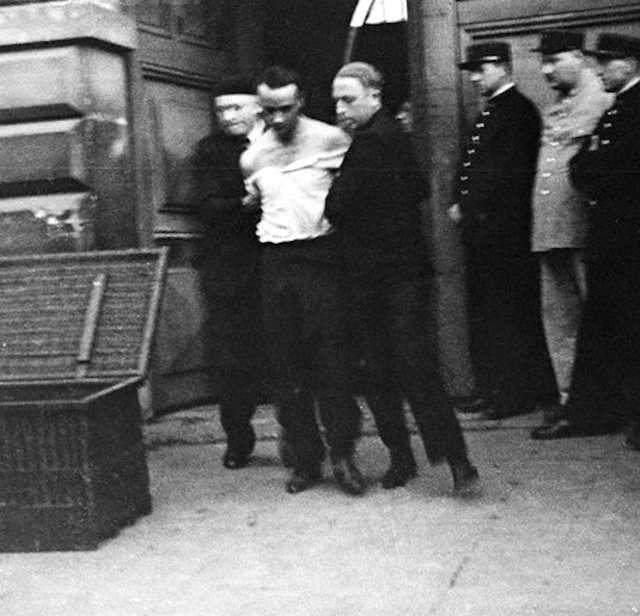

Eugen Weidmann, the last victim of the French guillotine, under arrest for murder. Wikimedia Commons

The guillotine is the ultimate expression of Law… He who sees it shudders with an inexplicable dismay. All social questions achieve their finality around that blade.

—Victor Hugo, Les Misérables

In front of the photograph of my mother as a child, I tell myself: she is going to die: I

shudder, like Winnicott’s psychotic patient, over a catastrophe which has already occurred.

Whether or not the subject is already dead, every photograph is this catastrophe.

—Roland Barthes, Camera Lucida

Pierre Vaillat celebrated Christmas by murdering his two eldest siblings. Apprehended days after his crime, he welcomed the arrival of a new year in a squalid prison cell while awaiting his trial. 1897 was surely a banner year for Vaillat: in March he was convicted of the double homicide, in April he perhaps enjoyed a breath of spring air as he was dragged from his cell to the awaiting guillotine.

Vaillat would, no doubt, have been long forgotten—an unremarkable criminal who, like thousands of others in the nineteenth century, expired at the end of the guillotine’s egalitarian blade—if not for a single photograph. There is a grainy, black and white photograph of Vaillat stumbling to the portable guillotine only a few feet in front of him. Taken April 20, it captures the criminal, arms shackled behind his back, flanked by a guard and a priest who, no doubt, read the condemned man his last rites. The near-pristine whiteness of the priest’s frock seems almost absurd at the bloody site of an execution.

Vaillat’s features are hard to make-out, and his form is blurred—the result of the writhing resistance, perhaps, of his unwilling body. His out-of-focus body is in sharp contrast to the gendarmes who sit on horseback, semi-circle around the site of the execution, to keep the gathered crowd of onlookers ordered and outside of the photograph’s frame. The outlandish plumage of their bicornes defiantly immobile, their bureaucratic calmness is rendered in well-defined focus.

Though the actual event may have been chaotic, in the photograph it is rendered ordered and clear: an execution is about to happen; within the photographic frame it is always about to happen. Vaillat remains forever suspended in his final living acts, fixed in these last steps towards his impending fate (or frozen, at least, until the photograph fades and his final living acts disappear forever). Vaillat’s photograph, like all execution photography, resembles a novel with no ending: its narrative is interrupted, the protagonist immobile. But the final chapter is known to us: violence is inevitable.

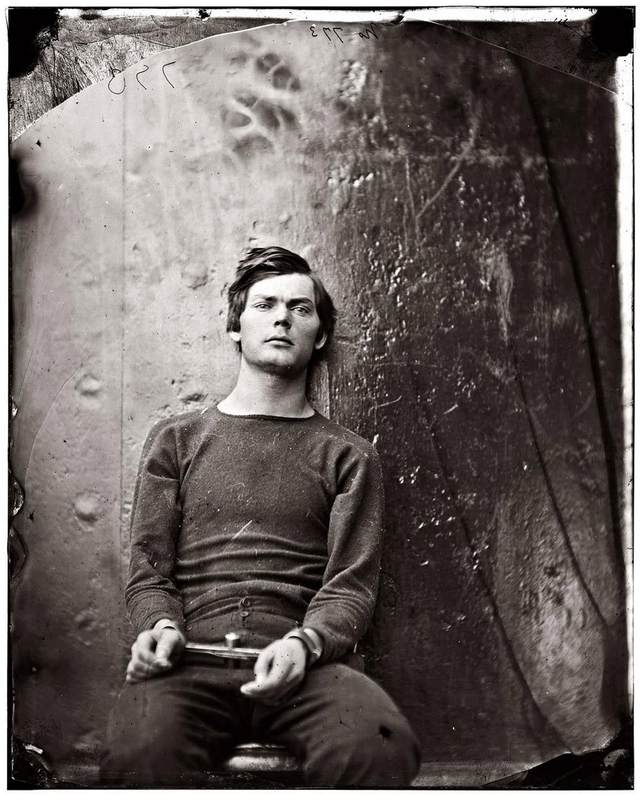

This is what Roland Barthes called photography’s “catastrophe,” the photograph’s unique ability to make a viewer “observe with horror an anterior future of which death is the stake.” But this catastrophe is not the brutal performance of an execution. Rather, it is a poignant bruising of the self that occurs while looking at photograph, that dreadful recognition that everyone photographed is dead or will be dead. That is the photograph’s punctum, the elusive, yet poetic, capacity to prick or to wound. In Barthes’s now canonical meditation on the photograph, Camera Lucida, he is pricked by a condemned man, by Alexander Gardner’s winsome portrait of Lewis Payne. “He is going to die,” Barthes writes of the Lincoln conspirator, “I read at the same time: This will be and this has been.” As Barthes considers Payne’s portrait—taken for reasons similar to Vaillat’s—he shudders “over a catastrophe which has already occurred.”

The execution photograph reproduces Barthes’s punctum in excess, carrying in its frame both impending death and the dead man’s terror. We know Vaillat is going to die, that the ritualistic theater of the guillotine has already reached its terroristic finale: it did so over a century ago. Yet Vaillat’s perverse portrait still compels, conjuring up a kind of static dread: this will be and this has been.

If the photograph encodes Vaillat’s death, then it’s made even worse by a crude-looking guillotine positioned at the center of the scene. Perhaps it’s because the photograph and guillotine are spectrally linked: Vaillat’s death will be (or has been) a doubly mechanical process. The guillotine will sever his head, the photograph will preserve his death somewhere in the “anterior future.” But perhaps the guillotine and the photograph share more than an abstract link to death. They are both symbols of technological modernity. In the hands of the panoptic nineteenth century, the guillotine and the photograph were deployed as tools in the spectacle of power: the guillotine terrorized while the photograph surveilled.

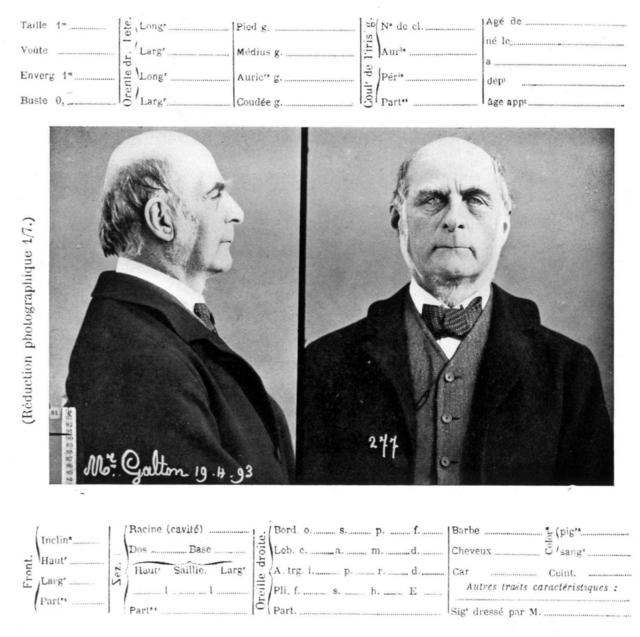

Paris police clerk Alphonse Bertillon devised a system of measurements that could be used to identify those arrested for crimes. Called anthropometry or bertillonage, the Paris police department adapted his system almost immediately after his first description in 1879. Bertillonage treated the criminal body essentially as a place that could be mapped with physical description and photography. Thus the profile and frontal photographs were accompanied by descriptions of notable markers (scars, tattoos, deformities, etc). The cards, once taken, were filed and used to identify repeat offenders and possible suspects. This particular card was made by Bertillon to demonstrate his system to British eugenicist (and inventor of the fingerprinting system), Francis Galton. Wikimedia Commons

A series of perverse portraits documented the end of Vaillat’s life: from the Bertillon card—the eponymous precursor to the modern mug shot—that would, no doubt, have been produced at his first arrest, to his execution, to (most likely) a photograph of his cadaver and severed head. The guillotine served the photographer in return: as the mechanical means to dismember the criminal’s body, it offered to the camera a new kind of body to capture and classify—the cadaver.

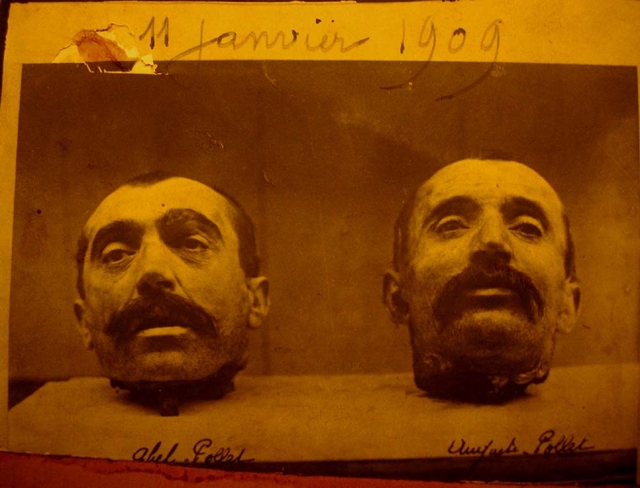

There are hundreds of nineteenth-century photographs of severed heads. Severed heads posed alone on tables, severed heads positioned at the foot of a headless bodies, decapitated heads of accomplices posed together—the possible arrangements seems endless. Between the severed heads, photographs of executions, portraits of criminals, and portraits of guillotine victims, what is the nineteenth century if not, as Daniel Arasse has suggested, a “extended series of heads cut off and cut up”?

The severed heads of convicted armed robbers and twin brothers Auguste and Abel Pollet, guillotined on 11 January 1909. BNF

The appeal of the executed body and its varying parts wasn’t limited to photography. Painters, too, tried their hand at the subject—Theodore Géricault’s Severed Heads, an oil sketch from 1818, remains one of the most harrowing treatments of execution pre-photography. But perhaps the most idiosyncratic treatment of the guillotine belongs to Antoine Wiertz. Wiertz, an obscure Belgian painter, produced a curious triptych titled Thoughts and Visions of a Severed Head (1853). The painting—and its accompanying text—attempts to recount the thoughts and feelings of a post-mortem head in order to determine if “the head, after its separation from the trunk, remain for a few seconds capable of thought?”

To this end Wiertz did what any good theosophist would have done: he obtained the services of one “Monsieur D, an expert magnetopath,” who obligingly accompanied Wiertz to the next scheduled execution where he hypnotized the painter at the base of a scaffold. “I asked Monsieur D to put me in rapport with the cut-off head,” Wiertz recounted, “by means of whatever new procedures seemed appropriate to him. Monsieur D acquiesced. He made some preparations and then we waited not without excitement for the fall of a human head.” Wiertz’s magnetopathic experience paid off in the most macabre manner: “The head of the executed man, saw, thought, and suffered,” the painter wrote, “And I saw what he saw, understood what he thought, and felt what he suffered.”

Wiertz’s writing about his hypnotic experience is, perhaps, more compelling than his confusing (and apparently degraded) triptych. The three panels of the triptych are here meant to correspond to time, to demonstrate the three distinct moments of agony: the severed head’s gradual recognition that it is, indeed, unattached and dying. “How long did it last?” Weirtz wrote, “Three minutes, they told me. The executed man must have thought: three hundred years.” Each panel thus represents one minute of a severed head’s death post-decapitation: the release of blade and removal, to the head’s “raging delirium” at the recognition of its detachment, and the violent suffering “in his viscera” as the head finally dies.

Thoughts and Visions of a Severed Head is jumbled and chaotic, much like the thoughts of the severed head recounted by Wiertz. And, no doubt, the painting would have relegated to the dustbin of art history, disregarded as a Romantic oddity if not for Walter Benjamin’s interest in the curiosity. Wiertz appears throughout Benjamin’s unfinished encyclopedia The Arcades Project, where he described the artist as a “painter of the arcades.” The criminal body—alive or dead, intact or dismembered—had been absorbed into the art of the Parisian spectacle. And the public execution was a part of that endless spectacle.

Reflecting on the nineteenth century, Benjamin found a correlation between the constitution of public Parisian consciousness and the consciousness executed in death. His entry on Wiertz in The Arcades Project is worth quoting at length as it articulates the interplay:

In Wiertz’s picture Thoughts and Visions of a Severed Head, and its explication. The first thing that strikes one about this magnetopathic experience is the grandiose sleight of hand which the consciousness executes in death. “What a singular thing! The head is here under the scaffold, and it believes that it still exists above, forming part of the body and continuing to wait for the blows that will separate it from the trunk.” A Wiertz, Oeuvres littéraires (Paris, 1870), pg 492. The same inspiration at work here in Wiertz animates Bierce in his extraordinary short story about a rebel who is hanged, and who experiences, at the moment of his death, the flight that frees him from the hangman.

Benjamin’s turn to story—Ambrose Bierce’s American Civil War short story, An Occurrence at Owl Creek Bridge (1890)—is telling. Wiertz’s painting, like his accompanying manifesto (what Benjamin calls “the caption”) is literary in structure; there’s a narrative arc, a finale. Perhaps that’s why Thoughts and Visions of a Severed Head could only be of interest, according to Benjamin, to “connoisseurs of cultural curiosities.” If Vaillat’s execution portrait is “catastrophic,” if it contains that elusive punctum, then it’s because the photograph resists narrative closure. Vaillat’s death is always about to happen, the “anterior future” is always close, but never imminent. Wiertz’s painting offers the finality of death—in the third panel “Everything goes black…The beheaded man is dead.”

Perhaps, too, the nature of the painting resists the terror of death. A painting acknowledges the overt theatricality that the photograph resists. By its very nature we know the painting to be fiction—Wiertz’ condemned man resists identification in his anonymity. Wiertz seeks answers and interests, but he wards off the terror of looming death.

Eugen Weidmann, a handsome German expat, hatched a plan. Weidmann decided that his previous career of petty theft had little room for advancement; beside, he wasn’t very good at it, having already spent five years in a small German prison. So he recruited two compatriots, rented a villa near Paris and began kidnapping rich tourists for the sole purpose of stealing their money. Weidmann proved about as good at kidnapping tourists has he was at petty theft. His first victim struggled, thwarting Weidmann’s plans. So the German and his compatriots decided to start murdering their targets; after all, dead men can’t struggle. After the fifth or sixth body, Weidmann was arrested.

It was his murder of the Brooklyn-born dancer, Jean de Koven, which particularly captured the media’s attention and turned his trial into a tabloid favorite. Weidmann’s trial was perfect for the spectacle of headlines and the flashbulbs of twentieth-century cameras: a handsome murderer, a smitten showgirl, a brief pas de deux before her grisly murder. Colette wrote salacious scenes for the Paris-Soir and Jean-Paul Sartre complained about the ceaseless coverage of “du noveau sur l’affaire Weidmann” in his 1945 novel L’Âge de Raison. Perhaps ironically, Weidmann’s conviction was aided by the photograph, when Koven’s body had been discovered it was surrounded by recently developed snapshots of her murderer.

After his arrest Weidmann’s photograph was splashed across the front pages of nearly every newspaper: a Bertillon card and a snapshot of him immediately after arrest, his head bandaged from the struggle during his arrest. Once confirmed as a criminal, Weidmann, like Vaillat, became a photograph where the specter of his impending death (“He is going to die”) haunted the images.

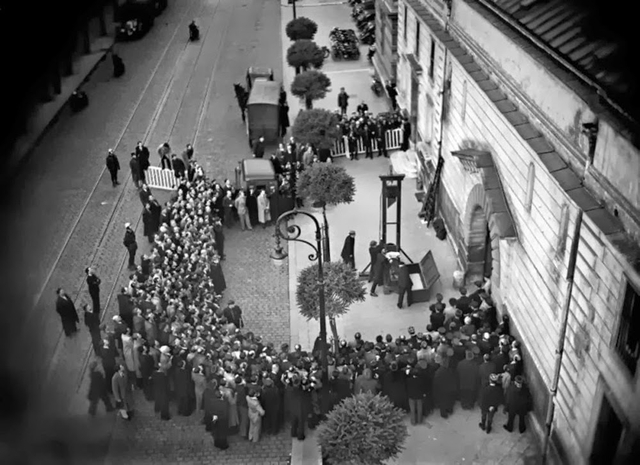

And Weidmann was, of course, executed for his crimes. The crowds that had watched his trial gathered for his execution. “Four hours in advance,” reported the International Herald Tribune, “six hundred persons pressed toward the Place Louis-Barthou. There were catcalls and jests with the Mobile Guard and occasionally a wave of cheering and whistling. In two brightly lighted cafes waiters joked and perspired and piles of sausage sandwiches, prepared in advance, went steadily down.” A little after 4 a.m. Weidmann emerged from his cell “eyes…tightly shut, his face flushed and his cheeks sunken.” His blue, prison-issued shirt had already been cut away from his neck and shoulders. Weidmann was placed in the awaiting guillotine, “his shoulders…startlingly white against the dark polished wood of the machine.”

Ten seconds later he was dead.

Weidmann, like Vaillat, would probably had been forgotten, effervesced like all tabloid criminals if not for the intervention of technology. Unbeknownst to Parisian prison officials, a film camera had been set up in one of the apartments overlooking the Place Louis-Barthou. The film recorded Weidmann’s execution and by the next morning photographic stills appeared on the cover of nearly every French newspaper.

Film still from Eugen Weidmann’s execution, June 17, 1939. Screenshot from the archives of France’s National Audio Visual Institute

The public was scandalized by their own violence; the government embarrassed. In response France banned public executions. Weidmann went down in history as the last man in France to be guillotined for the entertainment of the awaiting crowd (a dubious distinction). The government did not find fault in the grisly execution itself—of course it couldn’t have, that would have been an admission of justice’s guilt—rather it blamed the so-called unruly behavior of the savage crowd. The spectacle of bloodlust was, apparently, too powerful for film. Public guillotining was hidden behind the confines of the prison wall—privatized to conceal the spectacle from the very technology that it had worked in concert with.

The photograph, once a friendly companion to the guillotine, had turned on its old friend. In unsympathetic hands, the photograph cast doubts on the actions of the guillotine. Its public consumption questioned a system of justice that was supposed to appear natural.

I want to return where I began, to the static dread of Pierre Vaillat’s execution photograph, with Barthes “shuddering” at the site of a condemned man, and Victor Hugo “shuddering” at the sight of the guillotine. The two share a strange link between seeing and knowing, between seeing and suffering. The guillotine at once the site of the suffering and the terroristic specter of justice; the photograph a way to encode that death, to preserve the “catastrophe.”