Cambodian Dancers, Auguste Rodin, and the Imperial Imagination

On a July evening in Paris, a troupe of Cambodian dancers mesmerized Auguste Rodin. “I am a man who has devoted all his life to the study of nature, and whose constant admiration has been for the works of antiquity,” Rodin wrote. “They made the antique live in me.” The sculptor was so fascinated by the dancers that he followed the troupe to southern France, where they took up residency at the 1906 Colonial Exposition of Marseilles. Here Rodin drew them incessantly, obsessively.

The Cambodian Royal Ballet gripped the imagination of the French public during their visit to Paris and to the 1906 Colonial Exposition in Marseilles. But it was Rodin’s sketches of the dancers that immortalized this encounter between ancient Khmer dance and early twentieth-century France. Rodin did not represent the dancers realistically. Instead he recorded his psychological impressions, capturing the energy of Cambodian dance using techniques from European art. The sculptor’s appropriation of Khmer dance reflected primitivist currents of his time. But it also highlights the importance of public spectacles of cultural difference in pre-war France—spectacles like the Colonial Exposition.

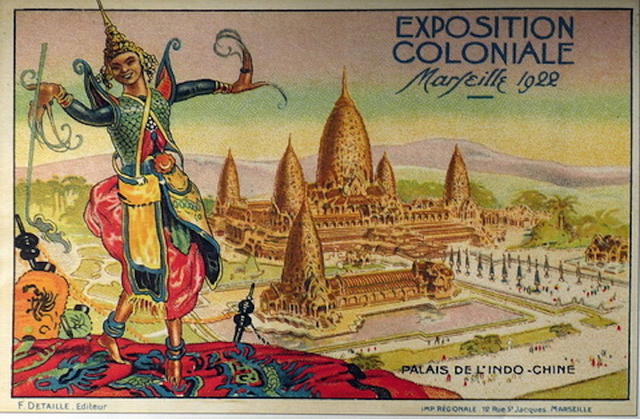

The Cambodian Royal Ballet arrived in France accompanying King Sisowath, who also attended the Colonial Exposition in Marseilles. It was the first trip of a Cambodian monarch to France. The Colonial Exposition aimed to present France’s colonies on a truly grand scale, serving as a prototype for later imperial exhibitions in Marseilles in 1922 and Paris in 1931. The Cambodian dancers performed in the Theatre of the Indochinese Pavilion (modeled on the Bayon temple in Cambodia) alongside a short film showing images of Indochina. King Sisowath’s pride in his dancers was matched by the enthusiasm with which they were received by the French. While Cléo de Mérode, a French dancer, had organized an approximation of Cambodian dance for the Universal Exposition of 1900, French audiences had never before had the opportunity to witness the ballet firsthand. Javanese dancers at the 1889 and 1900 Expositions had been the only non-European dancers to perform in France in recent years. There was, accordingly, great excitement for the Cambodian performances in 1906. The dancers were welcomed as representing “the timelessness of Cambodian culture” and portrayed as a counterpoint to Sisowath himself, who was treated as a comic and showy figure, “dressed up as a pagoda.”

A poster advertising the 1906 Exposition, prominently featuring a Cambodian dancer. Wikimedia Commons

By 1906, Auguste Rodin was a highly public figure. He had roughly fifty assistants, and his Thinker was on display in front of the Pantheon in Paris, the burial place for France’s national heroes. He was “certainly the contemporary French artist about whom most [had] been written.” His time consumed by bureaucracy and the demands of celebrity, Rodin was not, at this point, producing the sculptural masterpieces for which he is known. Rodin had long been interested in the dances of other cultures, sketching Indonesian dancers who he called “marvelous princesses” in 1889. Rodin similarly admired Sada Yacco’s performance of The Geisha and the Cavalier in 1900, and later became fascinated with a Japanese dancer known as Hanako.

Rodin’s feverish excitement for the Cambodian Ballet, however, surpassed this earlier curiosity. In Paris he attended two shows. When the Cambodian Royal Ballet returned to Marseilles after a week, Rodin followed them. He spent five days sketching, writing subsequently that he “would have followed them to Cairo.” In Marseilles, Rodin attended performances and made sketches at the pavilion where the ballet stayed, allowing Rodin to capture movements he had admired in performances. After their departure, Rodin copied the images again in his studio, outlined them in graphite and highlighted them using watercolor and gouache, arriving at a total of around 150 sketches. On the day of the dancers’ departure, Rodin was struck down with illness, having exhausted himself in his urgent attempts to record them.

The Cambodian Royal Ballet struck Rodin’s imagination due largely to his association of them with the cultures of antiquity. Rodin wrote that the ballet provided “a complete show that restored the antique by unveiling mystery.” He wrote that they “seemed to… have escaped from the bas-reliefs of the famous temples” at Angkor and from the “ancient stones” of French architecture, claiming in Les Cathédrales de France to have seen, in an angel at Chartres, a Cambodian figure. Rodin regarded the Cambodian dancers as embodying the past, as carrying “all that antiquity can contain” in their traditional dance. It is this Orientalist view of Cambodian culture that led him to consider the Cambodian dancers as ideal models, their bodies and movements uncorrupted by modern living.

This view of the Cambodian dancers as intimately linked with antiquity can be seen in the drawings themselves. The garments Rodin draws are simple but voluminous, large planes of fabric tied around the body like the togas of Western antiquity, as in Cambodian Dancer, in Right Profile. Rodin’s omission of visual context universalizes the figures; this dancer loses the costume that ties her to a particular dance style and similarly lacks individualized facial features. Movements, too, cannot be definitely linked to Cambodian dance; they are loose echoes of the dance Rodin sees. Rodin’s dancers are Cambodian primarily in name and, in images such as Six Studies of Cambodian Dancers, in the brown tones audiences would associate with Cambodian skin—though the performing dancers had their faces painted white so as to give a ghostly impression. In this way, Rodin’s focus on line and gesture, discarding unnecessary details, universalizes his models, rendering them timeless.

This view of the Cambodian Royal Ballet as having sprung from stone, as holdovers from antiquity, can be seen elsewhere. Another spectator described the dancers as “perfect copies of the old stone apsaras,” commenting particularly on the gestures and costumes. Few had visited Cambodia or seen the stone to which the dancers were compared, but photographs were widely circulated and, to the French public, Angkor and Cambodia were synonymous. The Cambodian dancers wore costumes modeled after the bas-relief of Angkor Wat, though more modest, and their headdresses resembled temples, constructed in decorative levels that tapered to a point. To French audiences, the ballet was visually linked with the past. For Rodin, this had an additional appeal; in these similarities the dancers sprang not simply from Angkor, but simultaneously from Ovid’s Pygmalion myth. Rodin’s sculptural practice was deeply imbedded with the idea that life and movement could be captured in stone, and the dancers suggested a more literal animation of stone. Their appeal may have been heightened through this imaginative leap; Galatea, to Rodin, appeared in these dancers.

Yet while Rodin likened the dancers to “those engraved in the stone ten centuries ago,” his renderings also modernized his subjects, using them as a starting point for invention and experimentation. Costuming linked the dancers to those of Angkor bas-reliefs, particularly the adorned sampot worn around the hips; while Rodin’s writings praise this costuming, he improvises the garments in his drawings. Rodin’s poses are based on those of the Cambodian Royal Ballet, but he gives them an energy and looseness that may not have existed in the slow, exacting Khmer tradition. While Rodin was amazed by Khmer dance movements, praising the dancers’ “continually flexed” legs and “the staccato shudders that the body makes,” these drawings draw their vitality from Rodin’s imaginative refiguring of the dancers forms. Rainer Maria Rilke was struck by the colors used in the drawings, the dancers transformed into “human flowers” through watercolour washes. Rodin’s Cambodian dancers were models for his imagination; he used some gestures he saw in the performances and discarded other aspects, creating his own version of Cambodian dance.

Rodin’s treatment of the Cambodian dancers more as inspiration than subject is reflected in his withdrawal from inclusion in The Story of the Cambodian Dancers in France, by George Bois, an admirer of Rodin’s sketches. Rodin withdrew from this project with the claim that his “drawings were not good from a specifically Cambodian point of view,” instead being “halfway between the European and the Cambodian.” Bois’s book was instead published with the sketches of Noel Dorville. In Dorville’s sketches, colours are bright and varied, capturing the energy of the costumes, while the childlike nature of the individual dancers can be seen in the innocent expressions with which they regard the viewers. The positioning of the dancers, “rigid in their heavy garments weighed with gold,” can be seen in postcards and photographic albums, the young girls appearing dwarfed by their attire. In these photographs, the viewer is drawn to the faces of the girls, who stare wide-eyed at the camera as they dance, too slowly for the camera to register motion. By contrast, Rodin’s dancers are always moving and are not individuals due to a paucity of detail. Their faces are often composed of little more than a scrawled mouth and dotted eyes.

Pierre Dieulefils_, Indo-chine Pittoresque et Monumentale. Ruins d’Angkor, Cambodge_, published c. 1909

Rodin’s drawings, despite the beauty of their execution, are symptomatic of European engagement with foreign cultures at the turn of the century. Rodin pulls the dancers out of context, stripped of costume, storyline, and individual identity. In transcribing the Cambodian Royal Ballet to paper, Rodin prioritizes the study of form and motion, denying the significance of Khmer dance and stagecraft as an art form in itself. The Cambodian Royal Ballet becomes simply source material, transformed by and subordinated into the European artistic vision. In 1906, Cambodia was seen as colonial periphery to France’s center, and so the appearance of the Cambodian Royal Ballet in France was a prime opportunity for the presentation of Cambodian culture to Europe. Rodin’s drawings, however, reduce the significance of Cambodia as a player in this encounter. When the dancers left and Rodin’s drawings went on display, it was the dancers’ impact on Rodin—rather than their skill as performers—which became memorialized. Thus while Rodin’s enthusiasm for the Cambodian Royal Ballet contributed to their preservation in national memory, his drawings transformed the dancers into European property, their bodies fodder for a distinctively French modern imagination.

The Colonial Exposition itself co-opted other cultures into European narratives, presenting Cambodia to the French people to celebrate the French colonial endeavor. The ballet was regarded as something Indochina offered France, who in turn ‘protected’ Cambodian culture from indigenous rule. King Sisowath initially regarded the trip as beneficial, giving his government political capital and a more prominent place amongst France’s colonies; it was expected, too, that a market for Cambodian dance would revive the Royal Ballet. Yet while the dancers proved successful in France as an exotic entertainment, this did not translate to their own country. Refusing 200,000 francs for a European tour, the Cambodian Royal Ballet declined from 1910 onwards. They appeared again at the 1922 Marseilles Colonial Exposition, advertised as “the famous Cambodian dancers,” but were unable to perform at the 1931 Exposition in Paris. A private Cambodian dance company instead appeared at the 1931 Exposition, advertised as the ‘Royal Ballet’ despite their origins, so as to ensure the public felt France’s colonial administration continued to protect the cultural riches that Cambodia offered.

An image advertising the return of the Cambodian dancers at the 1922 Marseilles Colonial Exposition. Wikimedia Commons

Cambodian culture was hijacked by the French colonial project, transformed into a symbol of French success as opposed to Cambodian talent. Prior to the arrival of the dancers, Cambodia was known to Europeans primarily via accounts focused on the exoticism of the country’s temples and jungle, the lack of human company, and the strange antics of animals. Louis Delaporte’s View of the Bayon is representative: the image depicts a huge temple, framed by trees. Though a Cambodian appears in the lower left corner of the image, almost hidden by undergrowth, he occupies a marginal place, an accessory used to indicate scale, dwarfed by his environment. Due to such representation and to the difficulty of foreign travel, in 1906 European audiences did not know Cambodia through its people. In visiting and performing in France, the Cambodian Royal Ballet, alongside King Sisowath, were amongst the first Cambodians to infiltrate French society. Rodin’s drawings, taking the dancers as their subject, became a prominent exception to the trend of depicting Cambodia as sparsely populated jungle. Rodin’s drawings, however, use the Cambodian dancers as accessories to his own artistic project of capturing form and gesture. While his drawings are of Cambodian people, their facial features are scarcely rendered, sacrificed in the pursuit of movement on a page. Rodin’s drawings took Cambodian girls as their subject, but still did not give them personhood. Thus while his drawings distanced the dancers from the Colonial Exposition’s subsuming spectacle, they readopted them for his own ends, not working from or toward an understanding of Cambodian dance.

The story of the Cambodian court coming to Marseilles has acquired an epic dimension, becoming an encounter through which the dynamics of the colonial relationship were played out in miniature. Originally regarded as an exemplar of beneficent empire, it was instead an acting out of the power imbalances of colonization: despite France’s posture as a caring friend to King Sisowath, the monarch was asked even to pay for the gifts he received while visiting France. Meanwhile he was racially ridiculed by a French media, referred to as a “coconut seller.” While these modes of thinking colored Rodin’s sketches of Cambodia, the sketches today draw attention to these events, and encourage reflection on the colonial project even as they exemplify it.

Contemporary reception of Rodin’s sketches has been mixed. The display of the Cambodian series at the National Museum of Phnom Penh in 2006 saw many of those at the opening, particularly dancers in attendance, describing his lines as “lazy” or “ugly”; it has been suggested that critical appreciation of Rodin’s drawings has been influenced by his lofty position in the Western artistic canon. Yet ambivalence to Rodin’s drawings can be seen throughout their exhibition history. The sketches at first reached a wider public in George Bois’s article in L’Illustration, published on the 28th of July in 1906. Bois noted that the “sketches may appear to be cursory and strange,” but reminded viewers that Rodin had produced great sculpture, linking distrust of the drawings with the mixed feelings that arise in “the uninitiated” when confronted with modernity. An article appearing in October of the same year in Je Sais Tous was more critical, describing the works as “haphazard, without any search for tones, nor for perspective or some kind of semblance of composition.” The drawings were first exhibited a year later at Bernheim-Jeune Gallery. The reviews for this show were largely positive, with Le Figaro going so far as to instruct readers that “it is imperative to have seen this.” In 1908, the drawings were shown in Brussels and in Leipzig. Following this, Rainer Maria Rilke published a short article that commented on his surprise at the lack of enthusiasm for Rodin’s drawings in Germany. Rodin himself felt that his drawings were underappreciated, writing to Antoine Bourdelle in 1907 that society did “not understand [his] drawings.” Bourdelle responded that “truthful works are not understood.”

While Rilke and Bourdelle appreciated Rodin’s drawings, not all those working alongside him saw his sketches in this light. Anthony Ludovici, Rodin’s assistant from June 1906, claimed that Rodin’s sketches, “give the spectator but a poor idea both of the models who stood for them, and of the artist who executed them,” crediting their celebration as due to “the misguided efforts of enthusiasts.” Ludovici claimed also that Rodin himself attached small value to his drawings, often giving them away, a suggestion that does not fit with Rodin’s repeated inclusion of the drawings in exhibitions he organized.

Ludovici saw this as evidence that the drawings were not worthy of appreciation; other critics of the time, however, recognized that the immediate and unrefined aspects of the drawings gave them liveliness and energy. Camille Mauclair, after writing that the sketches “are not themselves works of art,” conceded that they are “beautiful” and likened them to “a sort of passionate writing.” Similarly, Clément Jasmin, an art critic, wrote extensive praise for Rodin’s earlier sketches, regarding them as closely connected to his sculptural oeuvre. Just as Rodin’s writings have been of interest to art historical scholars, his drawings, too, are both beautiful and interesting. The use of drawing as preparation for other works does not detract from the merits of the sketches themselves.

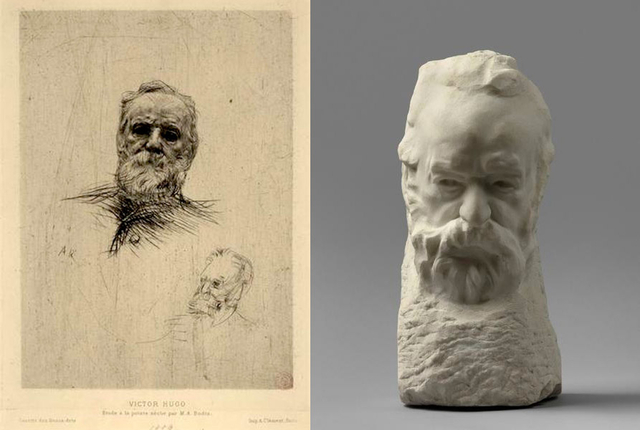

Rodin’s sketch (left) and sculpted bust (rught) of Victor Hugo. Musée d’art moderne et contemporain and Musée Rodin, Paris

While most critics agree that Rodin himself, whatever his thoughts on drawing, did not place his sketches as on the same plane as his sculpture, views differ on the relationship between his drawings of the Cambodian Royal Ballet and his subsequent sculptural work. Catherine Lampert writes that Rodin’s drawings were preparation for sculpture. It was, however, rare for Rodin to make sculpture from his drawings. While Rodin’s Bust of Victor Hugo was done from drawings, preliminary drawings exist for few of his other works. Rodin’s sketches of Hugo use shading to indicate recesses transferrable to a sculptural figure, with form and depth evident on the page; Rodin’s dancers, by contrast, are made of sparing lines and watercolour washes, ill-suited as preparatory drawings for sculpture.

It would seem, then, that Rodin planned no sculptural project involving the Cambodian dancers. George Bois closes his 1906 L’Illustration article with the note that related statues would appear “hopefully, at the next Salon d’Automne.” Bois appreciated Rodin’s drawings both as insight into his process and as beautiful in themselves; the apparent expectation is for sculpture embodying the same elements. Bois’s article is based on correspondence with Rodin, suggesting that it was his stated intention to complete sculpture based on the dancers. This, however, did not appear. In Rodin’s sculpted dancers and hands, where one might expect correlation, there is little influence. Rodin’s sculptures of dancers draw from Western ballet; the poses he depicts cannot be found in Khmer dance. The hands of the Khmer dancers, similarly, cannot be seen in Rodin’s sculpted hands. The Secret displays an intimacy foreign to his solitary dancers; these are the hands of two figures coming together, not a practiced pose. The most direct sculptural link comes in the form of two plaster casts from arms of Cambodian dancers, in poses from Khmer dance, with marks on the upper arm where the dancers wore armbands. These do not resemble any sculpture Rodin later made.

Rodin’s sketches of Khmer dance immortalized the Cambodian Royal Ballet’s 1906 visit to France, capturing the excitement of French audiences, and ensuring that this encounter between colonizer and colonized would not be quickly forgotten. In utilizing the Cambodian Royal Ballet for his artistic ends, Rodin’s drawings, like the Colonial Exposition itself, are beautiful. But they testify to a long record of European efforts to aestheticize foreign cultures rather than a true engagement with Cambodia. While Rodin never completed larger projects based around the Khmer dancers, plans for the Museum of Living Artists show their continued impact. To Rodin, as to his compatriots, the Cambodian Royal Ballet seemed to be the direct descendants of a hazy and ever receding pre-modern world. In sketching the dancers, Rodin created his own colonial myth.