Thinking Outside the Archival Box

What’s possible when we look at those neat rows of archival boxes and ask, “What’s missing?” Card catalog label at the New York Academy of Medicine, photograph by Ben Breen

Ten years ago, as a college senior, I embarked on my first “real” historical research project to write an honors thesis. I picked a topic (American medical missionaries in 19th-century China), read a stack of secondary literature, found an archival angle (a little-known doctor whose family had donated some of his papers to Yale), and drove up to New Haven to find out what being a historian was all about. In the quiet basement of the Divinity School’s library, I opened the first of the archival boxes I had ordered and began reading. Everything I would ever learn about the life and work of Josiah Calvin McCracken, M.D. sat within those half-dozen boxes.

When I think about that project now, there’s a part of me—the part trying to create a dissertation from chaos—that longs for such an orderly, bounded archive. But when I look at both my own research, on childhood in 20th-century Shanghai, and the historical monographs I choose to read, I see that my preference is for work that moves across and outside the archives, seeking to cast light on the lives of people who did not leave behind a tidy stack of personal papers. My shelves are filled with books about children, women, slaves, and other groups of people whose documentary trail is scant. The authors of those books don’t have linear feet of boxes to work through; in some cases, they can’t even be confident of their subjects’ names.

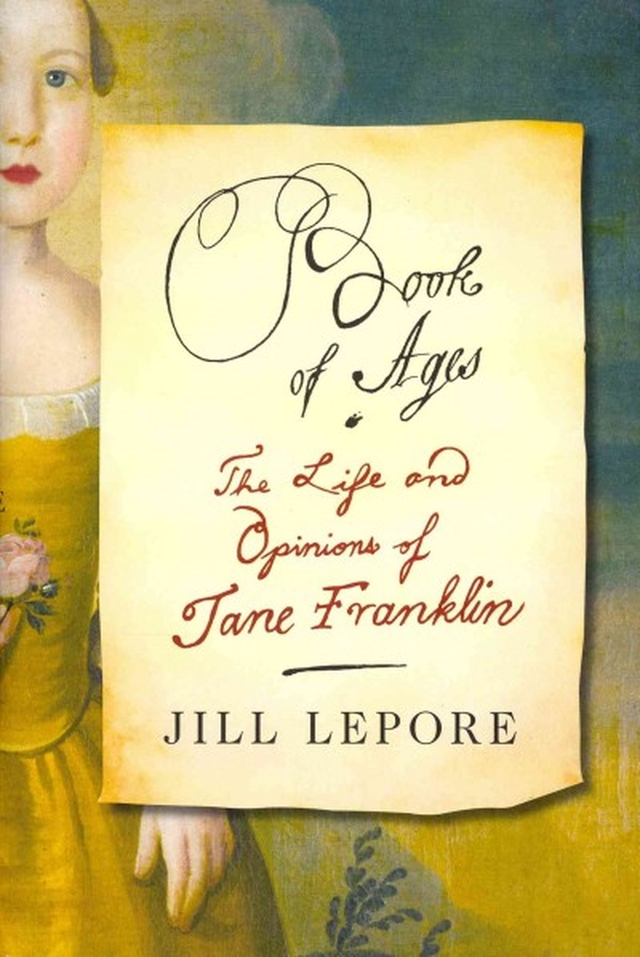

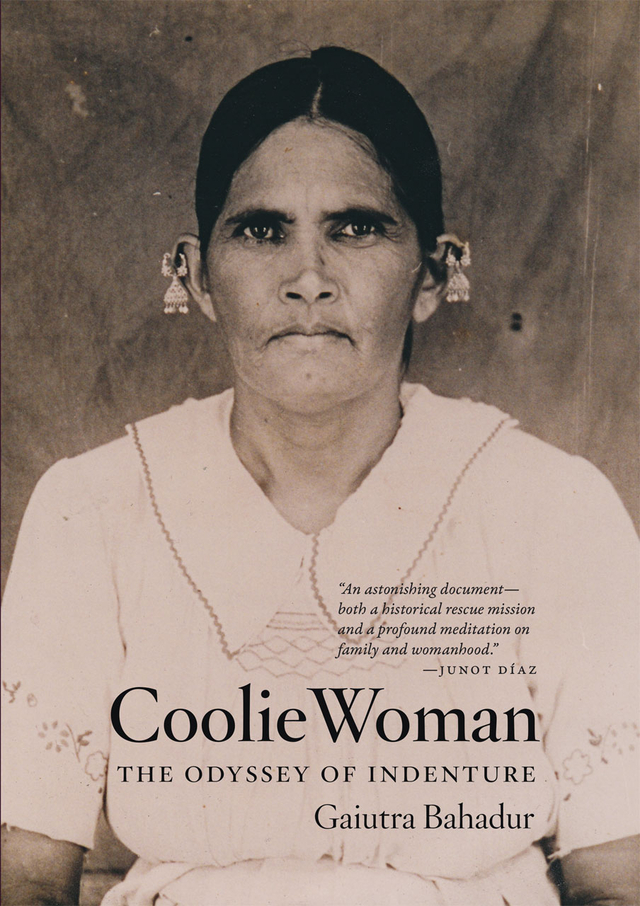

It might seem odd for a historian of modern China to write an essay about two books on topics that sit far outside her field and which, at first glance, have little in common: Jill Lepore’s Book of Ages: The Life and Opinions of Jane Franklin and Coolie Woman: The Odyssey of Indenture, by Gaiutra Bahadur. But I picked up both books because I’d read interviews with the authors that piqued my curiosity, as much for their methodology as their topics; both explore the lives of women whose obscurity requires creative research methods. Lepore, a professor of American Studies at Harvard and staff writer for the New Yorker, reconstructs the 18th-century world of Benjamin Franklin’s sister, while Bahadur, a journalist, has attempted to follow the trail of her great-grandmother, Sujaria, who traveled as an indentured laborer from India to Guyana in 1903 to work on a British sugar plantation. Jane Franklin and Sujaria lived more than a century apart, but the two books raise similar questions about the sources and approaches their authors employ to tell the women’s stories.

Jane and Benjamin Franklin, a tight pair in a family of seventeen children, carried on a correspondence that spanned six decades, though relatively few of Jane’s letters remain. Benjamin Franklin left home as a teenager and made his name (and fortune) as a writer and statesman; Jane Franklin Mecom married as a teenager, gave birth to a dozen children, and struggled to keep her family afloat financially, plagued by a ne’er-do-well husband. Lepore does not argue that Jane harbored a secret untapped genius that would have elevated her to Ben’s equal if she had lived in the era of women’s liberation. But she demonstrates that Jane Franklin, despite her poverty and limited education, read voraciously and wrote perceptively, sharing family gossip, recipes, and the occasional passionate political diatribe with her brother. She might not have been Judith Shakespeare, the gifted but stifled sibling that Virginia Woolf invented for William in A Room of One’s Own, but Jane Franklin had something to say about the world she lived in, and Lepore seeks to show that knowing Jane’s thoughts is integral to understanding Ben Franklin’s life and work.

Jane Franklin was an ordinary woman who is accessible to us largely by virtue of her relationship to a famous man. As Lepore says in a New Yorker podcast that accompanied her first article on Jane, in researching Jane Franklin’s life, she faced a “classic feminist evidentiary dilemma”: though Jane wrote scores of letters, only a handful survive. Benjamin Franklin’s papers, on the other hand, are substantial, and his letters, which often mentioned the content of his sister’s as he responded to her missives, helped Lepore piece together the story of Jane’s life. She finds inspiration in Jane’s “Book of Ages,” a spare, sorrow-filled volume, only sixteen pages long, in which she recorded the births and deaths of her children—a hint at how Jane’s life seesawed between happiness and tragedy. In addition to documents written by the Franklin siblings themselves, Lepore also draws on newspapers, legal documents, and popular books of the day to reconstruct the intellectual world of Jane and women like her: those who had received only a basic education and had little spare time to devote to leisurely pursuits, preoccupied with the rhythms of daily life in a house full of children.

Bahadur’s venture into the past began with a very personal set of questions about migration, identity, and gender. Seeking to understand her family’s route from India to Guyana to New Jersey, and the effect it had on her own sense of self, she decided to go back to the great-grandmother who left India as an indentured laborer—four months pregnant, apparently unmarried, and traveling alone. She hoped that knowing about Sujaria’s journey would help her figure out how it had resonated across the decades.

Because Sujaria left an even fainter archival imprint than Jane Franklin—nearly everything Bahadur initially knew about her great-grandmother came from a one-page exit permit, issued when Sujaria sailed from Calcutta to the Caribbean in the summer of 1903—Coolie Woman is most often a story about a group of people, rather than one person. Bahadur devotes a chapter each to the sequence of events that might have made up an indentured worker’s life, explaining how more than a quarter-million women were induced to leave India and travel on crowded ships to British colonies around the globe. On the sugar plantations of Guyana, women like Sujaria faced sexual exploitation and domestic violence, but they also married, raised children, and formed communities very far from their homes.

They composed songs and stories about coolie life that Bahadur integrates into her book, juxtaposing these descriptions of indentured labor with those in official British colonial documents, as well as newspapers. But despite her rich descriptions of life onboard coolie ships and in Guyana, there is still much that Bahadur cannot know, especially about Sujaria. She admits her wealth of unanswered questions: page 47, for example, contains only two declarative sentences. The remainder of the page is filled with Bahadur’s wonderings about Sujaria’s experiences and thoughts as she sailed from Calcutta. Exhaustive research can still only take us so far.

And that might be as true for historians of future generations as it is for us. In developed countries today, it seems like every moment of people’s lives is (self-)recorded, as we document dinners with friends on Facebook and tweet about sitting at home on Friday night with a bottle of wine and a good book. But how much has changed since the days of Jane Franklin and Sujaria? How much better will 22nd-century historians fare when they go to write the stories of today’s low-income residents of rural America, trafficked women from Vietnam, or child beggars in Rio de Janeiro? Archival silences aren’t a thing of the past.

“What would it mean,” Jill Lepore asks, “to write the history of an age not only from what has been saved but also from what has been lost? What would it mean to write a history concerned not only with the lives of the famous but also with the lives of the obscure?” We’ve left behind the days of biographies limited to the great men of history, but it still takes a combination of creativity, boldness, and luck to write books like these. Coolie Woman and Book of Ages offer impressive, sensitive portraits of women who might have otherwise remained obscure, providing further evidence of the valuable work that is possible when we look at those neat rows of archival boxes and ask, “What’s missing?”