The Peripatetic Life of Isabella Bird

When I am traveling, I find myself making mental lists, not of what I need to bring, but of what I’m missing. A scarf I haven’t seen since Lisbon, a sweater that was left on a plane, a book that may or may not be at a friend’s house in Brooklyn, photographs and notecards tucked into discarded magazines. I sift through what remains and wonder what else I’ve lost through so much packing.

I live a peripatetic life. Instead of renting one apartment, I stay in short-term sublets, sometimes for a few weeks, sometimes for a few months. I am therefore always on the lookout for packing miracles, some revelatory item that can carry me from Paris to Virginia to China. A company called Territory Ahead (slogan: Exceptional clothing for life’s adventures) carries a line of apparel called Isabella Bird, and because of the name, I assume it is meant for travelers. The items for sale range from a “Juliette Ikat Print Maxi Dress” to “Yucatan Peasant Tops.” I fail to see how any of it will help me in life at all, much less with life’s adventures.

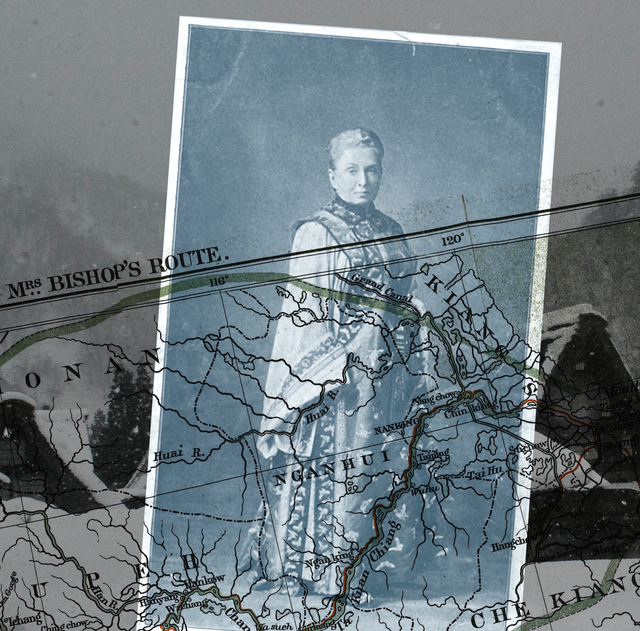

I doubt that the eponymous Isabella would have approved of such items, either. There is a sketch of her that is often used on the cover of her books: a somewhat dour Victorian lady swathed to the neck in clothing, a bow holding a hat on her head.

A lifelong explorer, Bird was the first woman to be a fellow in the Royal Geographical Society. She climbed volcanoes in Hawaii and had typhoid fever crossing the desert to Mount Sinai. A one-eyed outlaw professed his love to her in the mountains of Colorado. As an oft-quoted critic wrote in response to her book A Lady’s Life in the Rocky Mountains, “There never was anybody who had adventures as well as Miss Bird.” I doubt she accomplished such things in a Batik Floral Smocked Top.

Unlike myself, Isabella was an exceptional packer. When she explored the interior of Japan, she described the provisions with which she set out. She writes:

I have a folding-chair… and air-pillow for kuruma [rickshaw] travelling, an india-rubber bath, sheets, a blanket, and last, and more important than all else, a canvas stretcher [for sleeping] … I have brought only a small supply of Leibig’s extract of meat, 4 lbs. of raisins, some chocolate, both for eating and drinking, and some brandy in case of need. I have my own Mexican saddle and bridle, a reasonable quantity of clothes, including a loose wrapper for wearing in the evenings, some candles, Mr. Brunton’s large map of Japan, volumes of the Transactions of the English Asiatic Society, and Mr. Satow’s Anglo-Japanese Dictionary.

One hundred and thirty-six years later, it’s still a pretty good list for someone on the move. When I first discovered Isabella, I found a kindred spirit, a fellow wanderer to share my journeys with as I shared hers (see: “brandy in case of need”). I tucked one of her books into my carryon while headed to Barcelona, and then another while flying to California and later, Holland. While I wander, I freelance and take temporary jobs and try to visit as many places as I can. It’s a life that I frequently feel conflicted about, as did Isabella. She worried that she was being selfish. She worried she wasn’t committing herself to things that mattered.

On one front, however, we differ. While Isabella shared my wanderlust, her homesickness was of a different bent. It was not a longing for home, but her longing to be elsewhere that seemed to cripple her. The British Isles of her birth, attendant as they were to a restrictive Victorian sensibility, were more alienating environs than any foreign landscape, and she fell ill, suffering from pains and insomnia when not on the road.

Her homesickness was strangely literal.

When I was still quite young, my aunt and uncle bundled me into a minivan with my three cousins and drove us all to the Grand Canyon, snaking across the country from Virginia. My memories from this trip are episodic, like snapshots: lying in a field in Kentucky, seeing the Milky Way pouring through the night sky for the first time. Walking barefoot through a stream at Zion, pulling Maidenhair ferns off the canyon walls. Sitting on a rock, alone, watching the sunset over the Colorado River. Fighting with my three boy cousins in the backseat, a novelty for an only child.

But perhaps what I remember most clearly is the nausea-inducing vertigo of heartache that wracked me for the first few days, and recurred frequently throughout our travels. I felt physical aches at being separated from my parents for so long. I was homesick.

Swiss student Joannes Hofer introduced the term nostalgia—an amalgam of the Greek nostos, or “return home” and algia, meaning pain or longing—in the late 1600s to describe what in English would later be called homesickness. It was viewed largely as a medical condition, and was thought by many to have a particular hold on the Swiss. I’m vaguely embarrassed to admit when I am homesick, as today it implies at best a pre-modern parochialism, at worst a childish dependency. But in generations past, the condition was taken seriously; as historian Susan J. Matt describes in her book Homesickness, thousands of American Civil War soldiers sought medical care from doctors for the disease and Union troops were sometimes banned from playing “Home, Sweet Home” because of its negative effect in the ranks.

Born in 1831, Isabella was of this age that tethered temperaments to physical ailments. Her temperament was a nervous one, and she was plagued by pain that “dogged her all her life,” according to a hagiographic biography by a friend of Isabella’s, Anna Stoddart. When Isabella was eighteen, she underwent an operation to remove a tumor from near her spine and the family began spending summers in Scotland, which her father felt would be good for her health. Shortly thereafter, writes Stoddart, “Some sorrow, over which she brooded in the early fifties, was sapping her nervous strength, already impaired by the operation. Her health was far from satisfactory. It seemed as if quiescence so depressed her vitality that even the delightful months in [Scotland] failed to replenish its exhausted stores.”

“Some sorrow, over which she brooded in the early fifties.” I imagine Isabella, just reaching adulthood, up at three o’clock in the morning, when, as F. Scott Fitzgerald noted, “a forgotten package has the same tragic importance as a death sentence.” She was entering a society with few opportunities for an intelligent, ambitious woman; she had no desire for marriage, preferring to write pamphlets on free trade. Her lassitude concerned her doctor, who recommended a “sea-voyage” to help her recover.

An opportunity arose in 1854, when 22-year-old Isabella was sent to visit cousins in Canada. Her father gave her one hundred pounds sterling and told her to stay as long as it lasted. From Canada, she traveled to the United States, passing through Toronto, Boston, Cincinnati, Chicago, and later, down the St. Lawrence. From these experiences, she was able to publish her first book. Her publisher insisted she call it The Englishwoman in America (Isabella found the name pretentious due to her young age). To her delight, it sold well and she received what Stoddart describes as “substantial cheques from her publisher.” It was her income as a writer—both of books and for magazines such as The Leisure Hour—that helped her to finance her travels throughout her life.

By 1857, she was back in the U.S. at her doctor’s urging, extending a six-month tour into a year because of, she said, social obligations. But once she returned, her health deteriorated once again. Her father—whom she called “the mainspring and object of my life”—had died not long after her return and for a period, after she and her mother had rented an apartment in Edinburgh. She was frequently housebound. Isabella often lived the life of an invalid, participating in society as she could: committee meetings and private calls, mostly, as dinners out and large social gatherings exhausted her.

Her great companion was her younger sister, Henrietta, with whom she shared an unusually close relationship (they often opened letters with “my own pet” and other endearments). And although she guarded her time closely, she developed a small circle of friends in Edinburgh with whom she remained close for the rest of her life, including a Miss Cullen and Mrs. Blackie. This group of educated Edinburghers were “all keenly interested in the fragile little lady, whose spirited mind and sympathetic insight gave her an exceptional power of attracting and retaining friends.”

But Isabella worried that her fragile health had cocooned her in a world of idle comfort, inoculated from everyday demands and annoyances. In 1864, she wrote, “I feel as if my life were spent in the very ignoble occupation of taking care of myself, and that unless some disturbing influences arise I am in great danger of becoming perfectly encrusted with selfishness, and … of living to make life agreeable and its path smooth to myself alone.” Under doctor’s orders, she was free to avoid the people and activities she didn’t like, to wake up late and retire early. Throughout her thirties, she continued to write, but failed to flourish. As it had before her first travels, quiescence depressed her vitality.

In 1872, just shy of forty, Isabella, at Henrietta and her doctor’s urging, departed for Australia, which she hated. But she eventually found herself in Hawaii, then known as the Sandwich Islands, at which point she became the star in some sort of highbrow Victorian Eat, Pray, Love. She was enchanted by the tropical island and its delights as one can imagine a depressed, middle-aged British woman would have been. After attempting to ride sidesaddle up a volcano and finding it too painful, she decided to ride like a man, quite a controversial decision for the time. She embraced clothing that made this possible, the “riding dress” she would also wear in America (although her allowances for travel should not be read as a vote for progressive gender presentation; she once tried to sue a newspaper for claiming she had worn men’s clothing during one of her adventures). She was fascinated by the volcanoes, the poi, the tanned people swimming in tepid water. In letters to Henrietta, she says that the air was “always like balm.” “My health improves daily,” she wrote, “and I do not consider myself an invalid.”

She rode horses, slept in huts, and picked her way through lava beds. “I saw myself looking so young in a glass that I did not know it was me,” she wrote to her sister, “just as I have been startled in Edinburgh sometimes by seeing an anxious, haggard face and seeing it was me.” After spending some time on a sheep farm, a young Canadian proposed to her. She turned him down; Isabella was not so far gone down the road to Bohemia that a young hunter from the colonies would make for an appropriate mate. But she insinuated that if not for her sisterly bond, she may have been tempted. “It is pleasant to be among people whose faces are not soured by the east wind, or wrinkled by the worrying effort to ‘keep up appearances;’ who have no formal visiting, but real sociability; who regard the light manual labor of domestic life as a pleasure, not a thing to be ashamed of,” she wrote to Henrietta. When her time came to go she admitted “Every step now seemed not a step homewards but a step out of my healthful life back among wretched dragging feelings and aches and nervousness.”

A detail from the first edition cover of A Lady’s Life in the Rocky Mountains (1879). Lehigh University Libraries

From Hawaii, Isabella traveled on to America, the setting for A Lady’s Life in the Rocky Mountains, her most popular book. It was on this trip that her famous romance blossomed with Jim Nugent, better known as Rocky Mountain Jim. He was an infamous one-eyed outlaw at the time. It is worth quoting at length from her description of him, both because it gives a sense of her vibrant character sketches but also because of the obvious crush it reveals:

He has pathos, poetry, and humor, an intense love of nature, strong vanity in certain directions, an obvious desire to act and speak in character, and sustain his reputation as a desperado, a considerable acquaintance with literature, a wonderful verbal memory, opinions on every person and subject, a chivalrous respect for women in his manner, which makes it all the more amusing when he suddenly turns round upon one with some graceful raillery, a great power of fascination, and a singular love of children. The children of this house run to him, and when he sits down they climb on his broad shoulders and play with his curls.

When Rocky Mountain Jim confessed his love to her, Isabella was mounted on a horse, high up in the mountains of Colorado near what is now the town of Estes Park and was then little more than a meadow dotted by a handful of pioneer houses. But she turned him down, knowing that a drunken outlaw was not an acceptable choice for a lady.

If Isabella was motivated in her travels in part by an ache for those first youthful journeys to America, she also found herself changed by the interim years she spent tethered to Victorian society. She could not fully sever her ties to it, could not allow herself to fall in love or bring Henrietta to join her for a life in the islands. She stayed, instead, in limbo between the two, pulled back to her travels but always eventually forcing herself to return. Perhaps it was this internal division that caused her so much unhappiness; perhaps the seed of it was the sorrow she brooded over as a young woman. “I shall always in the future as in the past have to contest constitutional depression by earnest work and by trying to lose myself in the interest of others,” she wrote after returning from a trip to Japan, “and full and interesting as my life is, I sometimes dread a battle of years.”

In 1881, Henrietta died. She had developed typhoid fever and had been largely delirious for days, nursed by a friend of both sisters, Dr. Bishop. Isabella asked God to spare her “last treasure,” although she felt it was selfish to do so.

Isabella had just returned from an exploration of the interior of Japan, and her notes would later be published as Unbeaten Tracks in Japan, another acclaimed book. In the preface to the book, she says that she chose this country because it possessed “those sources of novel and sustained interest which conduce so essentially to the enjoyment and restoration of a solitary health seeker.” She ends with a note about her beloved Hennie:

Since the letters passed through the press, the beloved and only sister to whom, in the first instance, they were written, to whose able and careful criticism they owe much, and whose loving interest was the inspiration alike of my travels and of my narratives of them, has passed away.

It is a lovely sentiment, but does not touch on the soul-crushing grief she was experiencing. In a private letter she wrote, “The anguish is awful. She was my world, present or absent, seldom absent from my thoughts.”

Henrietta’s doctor—the aforementioned John Bishop—had been asking Isabella to marry him for years, despite her protestations that she was not the marrying type. Now she relented, though she insisted on wearing her black mourning dress at her wedding, giving the impression, as one friend noted, that she was marrying “under protest,” and that, “her real self was buried then in her sister’s grave.” She played the part of the attentive wife for nearly five years, during which she was often laid up as she had been before. Then her husband died, and while she truly mourned him, she realized that the best way to do so was to set back out on the road. With a new purpose, she dedicated herself to providing missionary medical care. She took nursing classes and then, at 57, departed for India.

In 1897, now in her mid-sixties, Bird wrote to Miss Cullen from Korea, “The weather is superb; the severe cold suits me. I have freedom, and you know how I love that! … I am so thankful for my capacity for being interested. What would my lonely life be without it?”

Bird traveled to China on the same trip, and, as was often her habit, extended her journeys as much as possible. “Instead of going home this spring,” she wrote

I have decided to remain for this year in the Far East. I find it quite impossible to tear myself away. Possibly when the heat sets in I may repent; but my health has been so much better for the five months of winter cold and I have been able to ride and walk as much as a person half my age could!

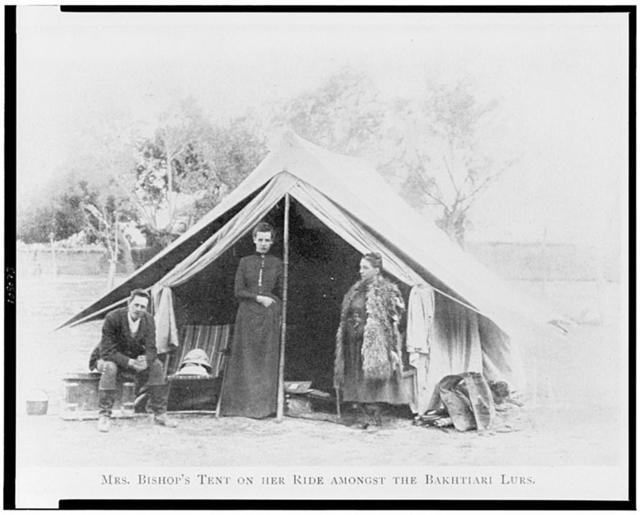

Despite her heartbreak, despite, at times, not being able to walk three hundred yards while living in Edinburgh, she continued ever onward. She had already charted unknown territory in Persia while acting as cover for a British agent; had made it through dangerous territory in Kurdistan; had climbed mountains in Tibet. Through it all she doled out medicines and gave advice on common illnesses to hundreds of people, even when exhausted after a long day’s journey. Having lost her sister and her husband, Isabella had lost the primary attachments she had with Scotland. She continued her letters to friends and her publisher, which eventually became her later books, but her trips were longer and more ambitious.

I like to imagine Isabella if she had stayed in Hawaii, riding fearlessly over volcanoes, her arms strong and tanned. Or I picture her living in the Rockies with her outlaw suitor, breathing the cold, clean mountain air. Would she have been happy then, in some new place, or would the dreaded battle of years have caught up with her once again?

I wonder the same thing for myself. When I first read about Isabella’s strange home-sickness, I was disappointed. This was not the dauntless travel companion I had signed up for; this was the bizarre reaction of a Victorian hysteric. I wanted her to laugh in the face of opprobrium and proudly flout convention. I wanted her to inspire me. The Edinburgh Medical Journal once called her “The Invalid at Home and the Samson Abroad,” saying, “it is only under special environment that special possibilities develop involuntarily.” I didn’t want to think of her development as involuntary. I also didn’t want to think that maybe she was simply running away, failing to face the challenges of her life, finding it easier to deal with flea-ridden inns and hostile Bedouins than to confront her own unhappiness.

Whereas once she had comforted me, her shortcomings now exposed all of my own worst fears about what I was doing. I couldn’t hack it in the real world, so I escaped into my travels, only to return home and expose my weakness once again. I was being indulgent, trite, silly. I wasn’t moving forward, as I had told myself, I was simply suspending time: avoiding the past and putting off future decisions by absconding to Tuscany, like some sad, powerless woman in a Henry James novel.

But lately, Isabella and I are traveling companions once again. In an essay adapted from her book The Future of Nostalgia, Svetlana Boym writes, “A cinematic image of nostalgia is a double exposure, or a superimposition of two images—of home and abroad, of past and present, of dream and everyday life.” Isabella wasn’t given the opportunity to stitch together these two images of herself; perhaps that is why her nostalgia went so awry. It’s also not quite right to say that she created an opportunity for herself; had it not been at the insistence of a doctor, I wonder if she ever would have traveled at all. But given little agency and few choices, she made the most of her circumstances and fought the part of herself that brooded over her limitations. She didn’t always transcend them, of course, and even when she did, she paid a dear price. But she battled on nonetheless, careening between her two selves, moving ahead in life as she did on her journeys, by plodding onward despite her hesitations.

At 72, Isabella had one more trip to China planned, but she wouldn’t make that one. Days before her death, an old friend inquired after her, knowing she had taken a bad turn.

“Tell her,” Isabella said, “that I am going home.”