Moved by Fire: History’s Promethean Moment

If all that changes slowly may be explained by life, all that changes quickly is explained by fire.

-Gaston Bachelard, The Psychoanalysis of Fire

Herakleitos famously observed that everything is change, and more specifically concluded that all things are an exchange for fire, and fire for all things. For him fire was a metaphor for dynamism. Fire changed matter. It moved: fast or slow, the world burned, and that burning accounted for Earth’s ceaseless motions.

By the nineteenth century, modern science had demystified fire. Energy replaced fire as a universal medium, and scientists reconceptualized flame as form of oxidation, a subset of physical chemistry. But the notion of fire as a motive power endured. Slow combustion in the form of respiration powered the living world. Fast combustion in the guise of flames transmuted landscapes. And internal combustion within mechanical chambers powered the industrial revolution.

Recently, in a New York Times essay, arch-rationalist Barbara Ehrenreich described a mystical experience she once had in which “the world—the mountains, the sky, the low scattered buildings—suddenly flame into life.” In fact, the fire was always there, if latent. It’s just that, barring some epiphany, we rarely notice. Likewise, it is everywhere in the past, yet almost nowhere in our formal histories. As with Ehrenreich, it seems that some special spark of intellectual transcendence needs to kindle in order for us to see it.

Fire history is Big History: it’s the story of what makes the Earth what it is. Our planet is built to burn. Life in the oceans fluffed the atmosphere with oxygen, life on land stuffed surfaces with combustibles. Combustion takes apart what photosynthesis brings together. The chemistry of life is a chemistry of combustion. It’s what makes the animate world move. Earth has been burning continuously for 420 million years. Fire is older than insects, trees, and Pangaea.

For eons, fire came and went as local circumstances permitted. Being a reaction, not a substance, fire was what its setting made it. It integrated climate, the mountains and ravines that altered local winds and biotas, the evolution of plants and the animals that fed on them (and the animals that fed on those animals). Some places and times overflowed with fire; others lay wet, dark, and inert. The fires of the Carboniferous period differ from those of the Permian. Miocene fires rippling over grasslands differed from Eocene fires that had no grasses to burn. The rhythms of fire were the rhythms of Earth as it spun and wobbled through space, bubbled with species lost and gained, and watched storm tracks, laden with lightning, wander over lands.

The Pleistocene, the past 2.6 million years (save the last 10,000) changed this dynamic as it iced over or dried out whole subcontinents. Yet the epoch we commonly identify as an Ice Age could be also be defined as the start of a Fire Age. It marked the greatest inflection point in fire history since lightning initially zapped dry vegetation in the Devonian. For the first time, a species acquired the capacity to start, and within limits, to stop fire. With Homo erectus that power became a permanent part of the hominin toolkit. Fire myths around the world proclaim that when we got fire we segregated ourselves from the rest of creation—and went to the top of the food chain. Whether or not hominins sought a domus, tended fire could not survive without one, which may well make fire the paradigm for domestication overall. Thereafter fire and humanity co-evolved. Our pact with fire was our first Faustian bargain.

Precisely when hominins learned to manipulate fire is unclear. But recent research suggests that fire, in the form of cooking, helps account for the leap into the genus Homo, who became physiologically dependent on cooked food. By boosting calories, and by detoxifying and softening food, controlled fire allowed us to exchange big guts for big brains. Experiments confirm that we cannot thrive or reproduce on raw foods alone: they simply cannot deliver the calories and they require more chewing, digestive juices, and intestinal machinery. With cooking that digestive process begins earlier. If the observations hold, they say that humans and fire have not simply co-existed but co-evolved. We are not only the keystone species for fire: fire is a keystone process for our existence.

But why only burn carcasses or tubers? Why not begin the process earlier and burn the habitats that produce those favored flora and fauna? If prize game are drawn to the greenup that follows a burn, why not burn that landscape, and wait for the fresh forage to lure bovids to it? If camas and mahias grow best in scorched settings, why wait for random acts of nature to produce them? With the evidence for the value of controlled fire all around them, early hominins began to cook landscapes.

With fire they could project their reach far beyond their immediate grasp, for one of the foundational properties of fire is that it spreads. Its power lies in its capacity to propagate. Landscapes that already had fire could be taken over and redirected by anthropogenic burning. Landscapes that lacked routine fire could acquire it. If its firepower allowed humanity to expand, so too humanity became the vector by which fire could propagate into new realms. The two became co-extensive. Humanity carried fire to Antarctica. Fire lofted humanity into space.

Consider a quick historical panorama.

There is little in our technology or habitat not touched by fire. Aboriginal economies of hunting and foraging routinely burned—light, early, and often. Flames could drive and draw game; they massaged biotas for favorable plants; they opened landscapes and routes of travel. In suitable settings, the outcome could resemble a rude landscaping, or in Rhys Jones’s striking phrase for Australian Aborigines, “firestick farming.” Still, the firestick could ignite only what was ready to be kindled. If too arid, too wet, or too cold, a spark would simply expire. Snow doesn’t burn. Nor do sand deserts. For humanity to expand its firepower, people would have to render the landscape more combustible.

This it did across much of the Earth by slashing, draining, loosing domesticated herds and flocks to chew and trample, and otherwise rearranging vegetation in ways that allowed it to dry out and carry fire beyond the constraints of climate and terrain. The upshot is, in common language, something like agriculture. There are horticultures based on floating gardens and dung heaps, and there are rich farmlands in floodplains where water takes the place of fire to fumigate and fertilize. But most agriculture requires the catalytic jolt of flame somewhere in its cycle. Even wet-field rice cultivators commonly burn off the stubble. And since fire requires fuel, the logical way to ensure fuel was to grow it. Agronomic critics long condemned fallow as a waste, and worse, something routinely burned, a double waste. In reality, the fallow was not burned to get rid of it, but was grown that it might be burned.

Such examples testify to fire as a bio-technology. But fire has been no less fundamental as a physical technology, for which, again, cooking serves as exemplar. People cooked wood, stone, metal, and liquids. With fire they hardened spears and shattered stone; distilled wood into tar and turpentine; melted sand into glass; smelted ore into iron and copper; baked clay into bricks. Fire was the basis for chemistry—philosophus per ignem, as the alchemists had it. Then fire was replaced by combustion, and combustion was disaggregated into heat and light. Fire disappeared from modern science as an informing principle and became a subset of chemistry, thermodynamics, and forestry.

Nor was fire alien to humanity’s built environments. If anything, it can be argued that structures—from caves to windbreaks—were shelters to protect fire. The hearth became the core of the house, as the pyrtaneum became the pyric equivalent to the village well, and the vestal fire the sacred fire of the tribe or state. But since villages were built of materials drawn from the surrounding environment, they burned according to the same rhythms of drought and wind. The cold front that slashed through the Lake States on October 8, 1871, caused Chicago’s fire to shift just as it did in the woods around Peshtigo, Wisconsin, where between 400 and 1,400 people reportedly perished. Urban fires were so common as to be expected. When people remade cities in less combustible forms, they did so out of materials such as brick, steel, concrete that had already, as it were, passed through the flames.

The great phase change came when people exhausted the firepower offered by Earth’s living biota and turned to its fossil varieties. They converted from open burning to closed combustion, from landscape fires and hearths to coal-fired furnaces, gasoline-powered cars, and natural gas-driven dynamos. For industrial societies fire as a presence disappeared. It vanished from houses, from factories, from fields, and continues to do so. It survives when the social order collapses due to wars, famines, or natural disasters. People no longer burned their lawns. Laws banned bonfires. Student dorms banned even candles. Barbecues abandoned wood and charcoal for propane. Free-burning fire existed in lawless zones and, as though it were an endangered species, in nature preserves.

The only fires that people living in an industrial society typically see are those on screens. Fire has become virtual. It has been deconstructed into machines and sublimated into electricity. If the present is the key to the past, then it no longer makes sense to search for fire in history because it has left the present as a fellow traveler of human history. It exists only in nature reserves and feral landscapes. It has become a subset of disaster narratives. It no longer enjoys the presumption that it is an informing principle to human life and Earth.

Those of use who see history with fire in our eye probably do so for personal rather than professional reasons. As it happened I began this essay while preparing for a research trip to the San Carlos Apache Reservation in Arizona. Out of a necessity that has become an opportunity, San Carlos has evolved a curious hybrid of managed fire on its wildlands. I wanted to see the outcome—and to track its history.

The odds were slight I would see any smoke. If they were fighting fires, the San Carlos fire officers couldn’t host me; nor if they were busy lighting them in the form of controlled (or prescribed) burns. I assumed I would have to search for fire’s spoor in still-blackened terrain and amid libraries. At least I didn’t have to explain my enthusiasms to the San Carlos fire cadre: they lived in a fire-drenched landscape, the highest region for lightning-kindled fire in the United States. For nearly every aspect of San Carlos geography and history, fire was a presence, if not a catalyst. The removal of free-burning fire, not its emergence, was the great disturbance in the force. Their challenge was to find a way to put it back into present day geography. Mine was to devise a way to reinstate it to history.

Everything I did to unravel that history had combustion in its character. I had driven an internal-combustion engine to the Hayden Library at Arizona State University in order to retrieve copies of old reports. The library was lit by electricity generated by a power plant fed by fossil fuels. Its furniture and rugs had been vetted for flammability by the Underwriters Laboratories. The number of people allowed within, the size and placements of its doors, the density of materials, some of Hayden’s core design features—all were dictated by building codes intended to prevent loss of life in the event of a fire. There were emergency exit signs everywhere. The elevators would shut down, replaced by protected exit stairwells whose entries were illuminated by electric signs charged by an autonomous power system. There were smoke detectors. There were fire alarms. Hayden Library was as fully sculpted by fire (or the fear of fire) as the grand terraces of San Carlos Reservation that stepped down from the Mogollon Rim to the Gila River.

It just wasn’t as visible—was in truth intended to be unseen. So it has proved with the fire histories written in Hayden.

The Hayden Library at Arizona State University; sunken entry at lower right, stacks to far right. Arizona State University

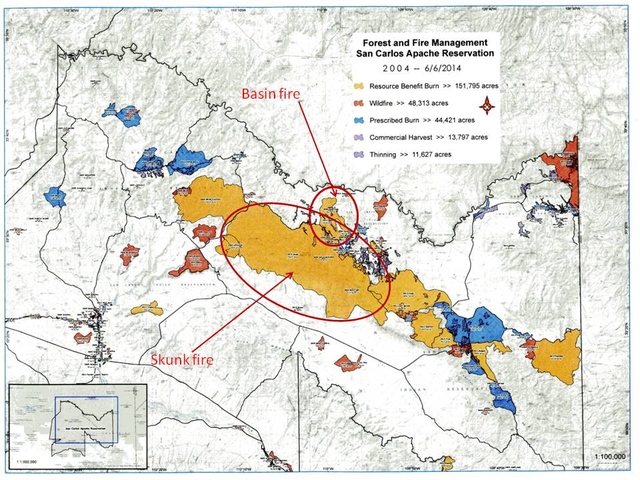

I assumed my expedition to San Carlos would likewise leave me not with fire directly but with its simulacra: I would have to trace its record in the literature and whatever blackened patches of landscape I could reach. I was wrong. The night before I arrived, lightning kindled two fires. I watched as the San Carlos fire cadre debated how to box and burn them—how to promote the good benefits latent in those ignitions without absorbing their potential bad side effects. For the next six weeks they identified firelines (boxed) and fired out from them (burned), and otherwise loose-herded the flames across the Nantac Rim. When the saga ended, the Basin fire had burned 6,000 acres and the Skunk fire a whopping 74,000 acres.

The past decade of fire—wild, prescribed, managed—at San Carlos Reservation. The Skunk and Basin fires are circled. San Carlos Agency

The episode was a master class in living with fire, and it was one wholly invisible to anyone not on site, a public primed to imagine fire as something feral and destructive. The San Carlos cadre had put useful fire back on the landscape. It was my job to put it back into history for scholars traditionally trained to see fire as incidental and disastrous.

Fire runs through the past like a Herakleitean current. Yet not trained to look for it, most people assume free-burning fire is a relic or hazard mostly banished from the modern world, and its appearance is like watching a bout of plague. They assign it to natural history along with grizzly bears, or to a human past that vanished with Shasta ground sloths. If fire appears as formal history, if it finds voice at all, it gets shunted to an appendix. Yet from time to time the blinders fall away and, like Barbara Ehrenreich, we discover that the world has been burning all along.

Footage of the Skunk Fire from three helicopter flyovers, 2014. From Bil Grauel, Bureau of Indian Affairs, National Interagency Fire Center.