To Russia, With Love

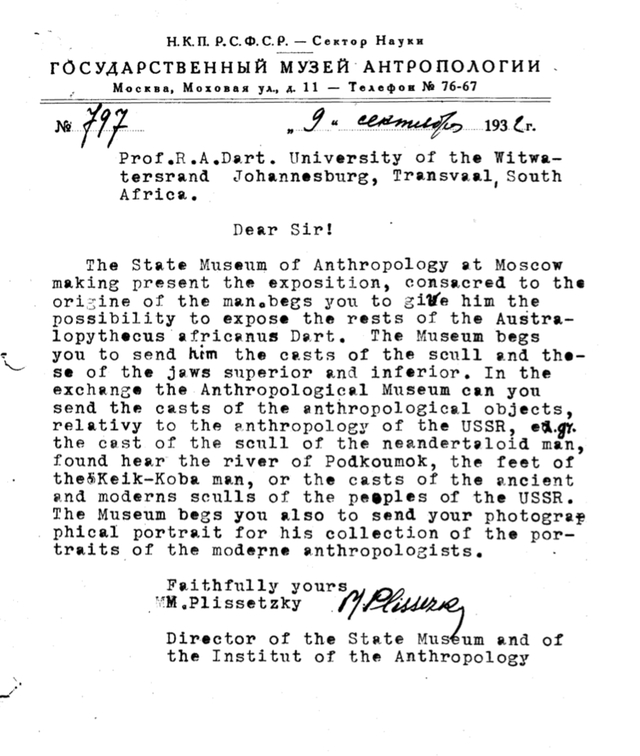

Scan of Professor Plissetzky’s letter to Dr. Raymond Dart. Courtesy of the University of Witwatersrand Archives

By the 1930s, paleoanthropologist Dr. Raymond Dart was used to his status as a pariah in paleo research circles. In 1924, Dart had discovered the Taung Child in northern South Africa. The fossil was one of the most unique fossils to enter human origins research, but Dart’s florid, sensationalistic—and yet correct!—interpretation of the Taung Child fossil in Nature in the first decade after its discovery meant that many scientists were wary of his science. Despite a suspicion of Dart’s interpretation of the fossil as a human ancestor (“an extinct race of apes intermediate between living anthropoids and men”), there was a flood of interest in the fossil itself. Museums and universities were interested in obtaining a copy of the fossil for their own study, comparison, and even display. Casts of the Taung Child were how the fossil could be circulated to scientific communities outside of the University of Witwatersrand, where the Taung Child was curated. Dart received innumerable inquiries about obtaining a copy of the Taung Child but one inquiry, in 1932, was most unexpected.

In December of that year, Dart received a letter from Professor M. Plissetzky, the director of the State Museum and the Institute of Anthropology in Moscow. Professor Plissetzky wrote to inquire about the possibility of obtaining a cast of the Taung Child (Australopithecus africanus): “The Museum begs you to send him the casts of the scull [sic] and these of the jaws superior and inferior.” Plissetzky hoped to display the cast of such a famous fossil as part of the State Museum’s human evolution and anthropology exhibits. The museum was chock-full of ethnographic artifacts, Paleolithic stone tools, and fossil casts—the exhibit’s banner in Moscow read: “Ancient Humans: Production and Consumption Elevate Humans Above Other Animals.” The Taung Child cast would have been right at home.

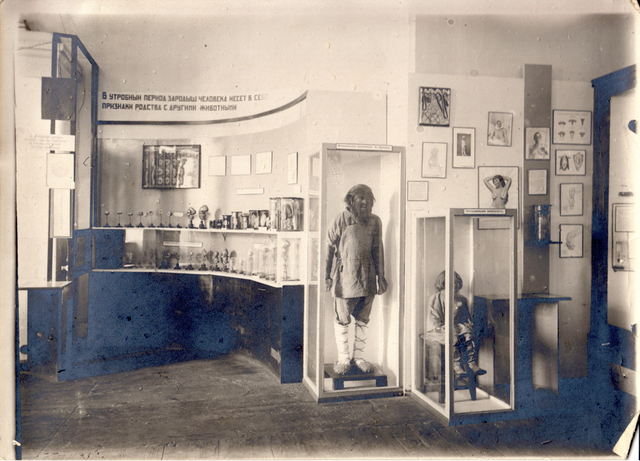

A photograph of Moscow Institute of Anthropology, as sent to Dr. Raymond Dart. Courtesy of the University of Witwatersrand Archives

In exchange for a cast of the Taung Child, Director Plissetzky offered to send Dart several casts of fossils from the USSR—a Neanderthal from Kiik-Koba (now in the Ukraine) and other early humans. Dart was enthusiastic toward Professor Plissetzky’s request, particularly as copies of the Soviet fossils Plissetzky mentioned were extremely difficult to come by. However, Dart quickly found that diplomatic and global tensions in the early 1930s between the USSR and Europe made the logistics of how to send a cast of the fossil to Moscow rather tricky. Although all request for copies of the Taung Child were sent through London—where the casts were created—the question of how to send a cast to Moscow was met with more difficulty than similar inquiries. The request from the Institute intrigued Dart enough to write back to Plissetzky to inform him that the cast would be en route, whereas other requests were simply forwarded to London. Dart wrote to the creators of the cast, the well-respected R.F. Damon & Company in London, to facilitate sending the Taung Child cast to Moscow.

In the first part of the twentieth century, casts of fossil specimens were key to paleo sciences. Because actual fossils were too valuable and rare to ship to international researchers, casts of fossils circulated in their stead. This movement of casts was not unlike the exchange of other material objects in the 1930s—prints of feature films circulated among theaters and bronze casts of Rodin sculptures moved among art museums. In the early days of human origins research, paleoanthropologists would offer to trade casts of “their” fossils to other researchers in different areas of the world, who had different looking specimens—the casts became a social currency. Professor Plissetzky’s offer to share rare USSR fossils with Dart, in exchange for a cast of Dart’s South African find, was in keeping with the flow and exchange of scientific information.

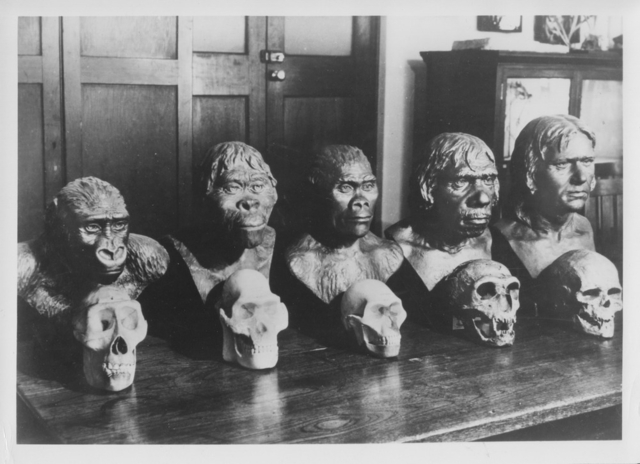

Casts by R.F. Damon & Company. All of Dart’s communication with the company ran through Mr. F.O. Barlow. Courtesy of the University of Witwatersrand Archives

Why not just a photograph? Or stereoscopic image? Dart’s colleagues—both his collaborators and detractors—wanted to see copies of the fossil in order to examine the fossil’s anatomy for themselves. People outside of academic circles had heard of the famous fossil and expected to see it in public museums. In order to circulate the fossil for study and display, accurate copies of it had to be made. Dart turned to R.F. Damon & Company, one of the premier casting companies of the early twentieth century, to create the fossil’s model.

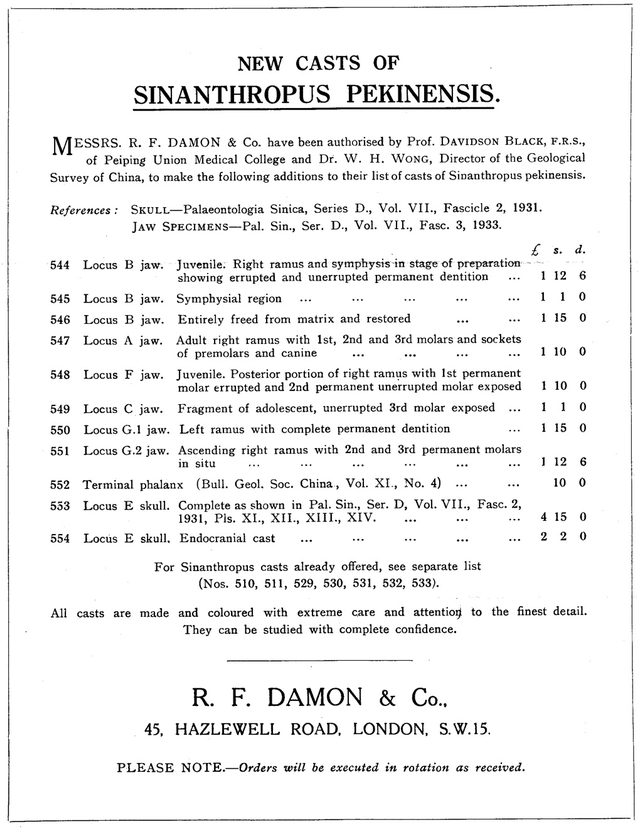

The nineteenth-century fossil business was nothing if not lucrative. By 1932, when Professor Plissetzky first wrote to inquire about a fossil cast, the company was run by Robert Ferris Damon, having inherited the fossil casting company from his father, Robert Damon. Damon Sr. had established himself in the fossil business in 1850, working to secure real fossils and fossil collections for museums and facilitating the acquisition of fossil specimens for institutions as well as wealthy collectors. By the end of the 1800s, Robert Damon, senior, had expanded the company and its mission to undertake creating casts of all types of fossils and the company maintained an impressive catalog of fossil specimen casts. In the early days of the casting company, say 1850-1900, most of the casts and models focused on fossil marine shells and fish. All of these casts were made of heavy plaster and were used by museums in collections as well as in displays.

The cast became a proxy for the fossil object itself; by using replicas of the fossils, it was relatively easy to circulate scientific data and to foster connections between researchers and museums. It also meant that access to the fossil casts was controlled through both the fossil’s discoverer (by deciding whether or not to create a cast in the first place) and the casting company (by setting prices and creating accurate reproductions of it). Casts made the exchange of scientific information easier and they represented a huge commitment of time, resource, and investment from the museums’ perspective.

R.F. Damon & Company’s advertisement for replicas, reconstructions, and casts of Sinanthropus pekingensis, popularly known as Peking Man. Courtesy of the University of Witwatersrand Archives

By the early twentieth century, R.F. Damon & Company expanded its paleontological collections to include anthropological casts and models. Due to a burgeoning interest in obtaining casts of human ancestors and anthropological specimens, the company focused on skulls, jaws, and teeth of humans and their ancestors. With the discovery of fossil hominins in Java (Pithecanthropus, or Java Man) in 1897; Europe in 1912 (the infamous Piltdown fossil); and Africa in 1924 many researchers and museums wanted access to copies of fossils. In order to put the fossil in motion within scientific and popular circles, it was necessary to find a way to replicate and disseminate copies of the fossil to researchers and museums—for many of the reasons that Professor Plissetzky wanted to obtain a cast copy of the Taung Child.

Creating a cast of a fossil is a difficult process—it’s a balance of art, technology, and science. The cast needs to capture the intricacies and the overall shape of a fossil. As it is rare for a fossil, itself, to be sent around for scientific study, the cast became the material object under study. The cast of the fossil can be ordered and displayed in museums and universities, casting (as it were) a much wider scope of influence than the original fossil, itself. Certainly, the original fossil is studied, photographed, and sketched and in modern casting technology, three-dimensional scans and various other digital measurements are taken. But it is the cast of the fossil that propagates through scientific, educational, and museum circles, lending a sense of credibility—even a legitimacy—to the fossil copy.

Dart held the “copyright” on the Taung Child fossil, according to R.F. Damon & Company’s paperwork and Dart was paid royalties based on how many fossil casts were sold. Dart worked with the company’s Mr. F.O. Barlow on both the nitty-gritty details of creating and describing the fossil casts as well as in sorting out the financial ledgers; dozens of letters between Barlow in London and Dart in Johannesburg hashed out the fossil’s financial deals. When Dart originally approached R.F. Damon & Company, he thought that each fossil cast ought to sell for more than what other, similar hominin casts had sold for (e.g. Pithecanthropus). Mr. Barlow begged Dart to reconsider his position about the cost of the cast, as Barlow noted, “The prices you suggested would result in killing the demand and would create in my customers a feeling of resentment which I am not willing to incur.” Once the question of price was properly sorted out, the company sold a lot of casts.

In 1932, for example, casts of the Taung Child were purchased by museums across Europe, North America, South Africa, and even Australian Correspondence peppers multiple museum archives (such as London, Glasgow, American Museum of Natural History, and the Natal Museum, to name a few) inquiring about the possibility of obtaining the cast. In 1936, sales dropped and casts were only requested by the London Horniman Museum, Geneva Natural History Museum, Oxford, Oslo Dental School, and Johannesburg Dental School. Mr. Barlow speculated that was due to global financial crises.

However, not all researchers were satisfied with examining a cast of a fossil. In 1933, J.H. Power from the South African School of Mines in Kimberly, wrote to Dart asking Dart to send him photographs of the fossil in order to properly measure anatomical features of the Taung skull since, for reasons unexplained, Power didn’t trust the accuracy of the cast. Dart had sent Power photographs of the cast and Power wrote back, appreciative of Dart’s time, but insistent on seeing the actual fossil, as represented by the photograph. Power preferred to examine the fossil by photo proxy, rather than through a cast.

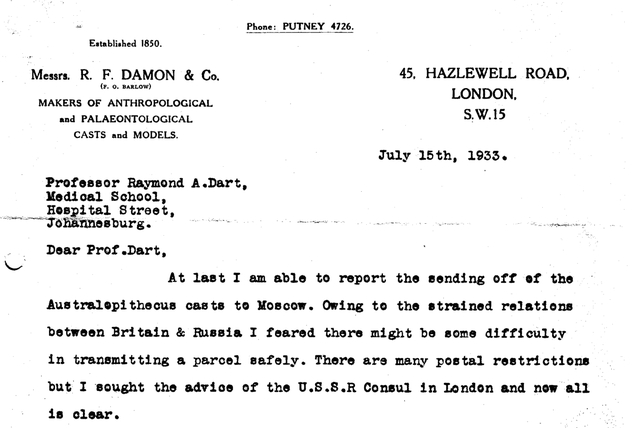

After receiving Professor Plissetzky’s request for a Taung Child cast, Raymond Dart arranged for a the University of Witwatersrand to pay for R.F. Damon & Company—courtesy of Mr. Barlow—to send a copy of the cast to Moscow. Mr. Barlow wrote to Dart:

At last I am able to report the sending off of the Australopithecus casts to Moscow. Owing to the strained relations between Britain & Russia I feared that there might be some difficulty in transmitting the parcel safely. There are many postal restrictions but I sought the advice of the USSR Consul in London and now all is clear.

Letter from Barlow to Dart, explaining the handoff of the fossil cast. Courtesy of the University of Witwatersrand Archives

Barlow concludes his letter, reminding Dart that payment for this particular cast is owed.

Professor Plissetzky did, indeed, receive a copy of the Taung Child cast. The fossil hominin exhibit in the State Museum and the Institute of Anthropology, Moscow, had held casts of Pithecanthropus from Java and notes fossils found in Zhoukoudian, China. In his original request, Plissetzky had sent photographs of the exhibit to Dr. Dart to show him how and where the fossil cast would live.

These exhibits filled the State Museum and the Institute of Anthropology in the early 1930s. They illustrate a strong commitment to influences of German evolutionary theory (with quotes from Ernst Haeckel) and to Marxist ideology.

For two generations, the R.F. Damon & Company put hominin casts like the Taung Child and other famous fossils in motion through museums and institutions. As other, newer technologies have developed for sharing a fossil’s data—3-D scanning, 3-D printing—the Damon casts become a rather material reminder of the process of older methods of “doing science.” In the paleo-sciences, Damon casts have become bits of fossil relics, themselves. But the exchange of information, data, and curiosity that sparked Professor Plissetzky’s inquiry to Dr. Raymond Dart are carefully curated sentiments with those plaster casts.

Acknowledgements:

The author would like to acknowledge the expertise and help of the Natural Science Collections Association Discussion List: Stuart Baldwin; Malcolm Chapman; Neil Clark; Jenny Cripps; Nigel Monaghan; Holly Morgenroth; Maggie Reilly; Mark Simmons; Paolo Viscardi; and especially Jan Freedman for details and discussions about museums’ collections. The author would also like to acknowledge Tanya Kulik and Dr. Dmitrii Makarov and for their help with Russian translations; Dr. Michael Gordin for helpful discussions about history of science in Russia; and the archives at the University of Witwatersrand. The author would also like to acknowledge the Institute for Historical Studies at the University of Texas at Austin.