Editorial Letter: In Motion

The tymes are chaunged as Ovid sayeth, and wee are chaunged in the times.

—John Lyly, 1578

A blink of an eye takes place in roughly one third of a second.

Bamboo can grow up to thirty-five inches in a single day. Orca whale babies leave the womb seventeen months after they are conceived. We begin to recognize the reflections of our own faces in mirrors when we are around eighteen months old.

The Roman Empire lasted for 426 years—or 1,484, depending on how you define “Roman” and “empire.” It takes 226 million years for the sun to complete a single orbit around the Milky Way’s galactic core. The evaporation of all black holes and the dark era of the universe might begin in around one googol, i.e. one thousand one hundred million years. The universe might contract back into a singularity. Or it might keep expanding forever—and life with it.

There can be no sense of history without a sense of movement. The articles in this issue are about many kinds of motion, from the sojourns of Cambodian dancers in 1906 France to the stuttering flicker of early silent film, and from the rise and fall of Brazilian hot air balloons to the travels of baby teeth earnestly dispatched by St. Louis schoolchildren in the name of Science.

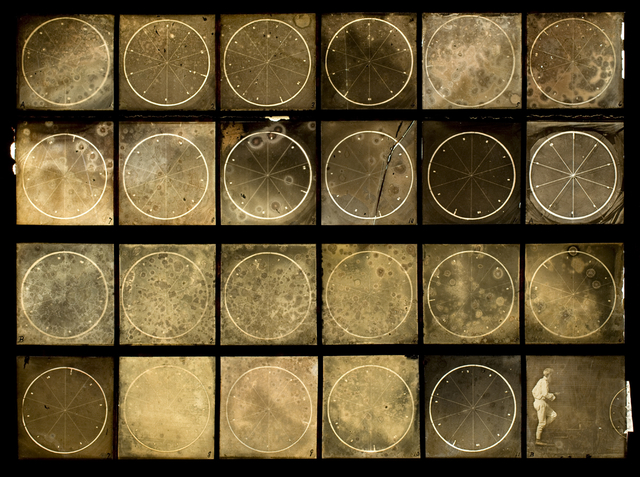

Eadweard J. Muybridge, “Sequenced image of a rotating sulky wheel and self portrait,” ca. 1887, negative, gelatin on glass, George Eastman House. Wikimedia Commons

What sets these pieces apart—and, we hope, draws them together—is their sensitivity to motion in time. Our first chapter, “People in Motion,” is the most straightforward, mapping as it does the itineraries of individual human beings. Mary Draper’s “The Man Who Was Buried Twice” is a meditation on a Jamaican gravestone and the singularly lucky life it commemorates. Cara Parks examines a nineteenth-century traveler’s sense of home alongside her own in “The Peripatetic Life of Isabella Bird.” “Don’t Cry for Me, Elanthia” is a history of that most unpromising of subjects—a mid-90s AOL text-based game—and the rapid-fire form of reading that sustained it. Ryan Keller reconstructs a deadly fistfight in 1900 West Point that centered around his own great-grandfather, and Lydia Pyne takes us to a museum in Soviet Russia that earnestly desired a cast of a South African hominid’s skull. Finally, Stassa Edwards delivers a powerful essay on the guillotine and the photographers who catalogued its horrors, leaving frozen records of lives about to be lost.

Chapter two of our issue is about objects in motion—from the Brazilian balloons followed by Felipe Cruz to the silent film images that conjure up the life of a clown who inspired Charlie Chaplin. Michelle Maria Capistrán’s “Amazons, Pirates, and Turtles on the Island of California” is about precisely what it sounds like—with an emphasis on the unusual historical trajectory of turtle meat, a topic we appear to be fond of. Kathryn Lehman passes between present and past as she visits the ruins of a Bolivian rubber town built alongside an Amazonian tributary’s rapids, and Steve Pyne considers that ultimate object—or rather plasma—in motion: fire. Rounding out the chapter, Caroline Jack and Stephanie Steinhardt offer up a spectacular piece of historical research—in turns bizarre, funny, and sad—about an unexpected intersection between the tooth fairy and the atom bomb.

An extremely early color photograph taken by Sergey Prokudin-Gorsky in Tsarist Russia circa 1909. The blurred forms of the photograph are artifacts from Gorsky’s proprietary color printing technique. Library of Congress

The third and final chapter of the present issue concerns itself with “Ideas in Motion.” Kristen Burton draws on years of research into the history of drunkenness to reflect on the “Blurred Forms” of the early modern inebriant. Anna Blair reconstructs the hypnotic movements of Cambodian dancers performing in Belle Époque France—and the dehumanizing obsession of the man they hypnotized, Auguste Rodin. Elizabeth Weinberg’s “A Satisfying View,” a piece of original fiction, evokes the small changes that lurched a community into radical upheaval in 1965 Bali. Ernesto Bassi charts “The Space Between” the stated and actual itineraries of West Indies sailing ships, while Maura Cunningham’s review of two new books about overlooked women in history reflects on the itineraries that archival boxes might not contain. Finally, David Lerer’s “The Hawaiian Invasion” rounds out the issue with a story about the complex musical legacy of a colonized culture.

The Appendix itself is in motion this fall—watch our blog in the coming weeks for an update about a significant shift in our format. “Tempora mutantur, nos et mutamur in illis,” as the Romans said: Times change, and we are changed with them. We hope they change you for the better.

Yours in history,

Benjamin Breen

Felipe Cruz

Christopher Heaney

Brian Jones

Amy Kohout

Marissa Nicosia

Lydia Pyne