The Man who was Buried Twice

The earthquake that swallowed up the Sodom of the West Indies, and aftershock that regurgitated one lucky merchant.

One morning, a man named Lewis Galdy found himself swallowed up by the Caribbean Sea. Galdy, a French merchant, was among 6,500 people living in Port Royal, Jamaica, in the last decade of the seventeenth century. By this time, this notorious privateering haven had developed into one of the most densely populated cities in the Western Hemisphere. Its sizeable population lived and worked among approximately 2,000 structures, all of which were crowded into a mere 53 acres of land.

At 11:42 am on June 7, 1692, an earthquake sent two thirds of the town hurtling into the ocean. For three minutes tremors pulsated across the cay, transforming its paradaisical landscape into a bed of quicksand. The sandy soil of Port Royal resulted in a geological phenomenon known as liquefaction. When fault lines shift under a sandy location, instead of shaking, the earth quite literally envelops whatever is on its surface.

One witness strove to explain the horrifying scene: “I found the ground rowling and moving under my feet,” he recalled. He then “saw the Earth open and swallow up a multitude of People, and the Sea mounting in upon us over the Fortifications.” In the aftermath of the earthquake, the President and Council of Jamaica wrote to the Lords of Trade and Plantations in England, explaining “Two-thirds of Port Royal were swallowed by the sea, all the forts and fortifications demolished and great part of its inhabitants miserably knocked on the head or drowned.”

Port Royal’s reputation as “the wickedest city on Earth” led many to believe that the city and its inhabitants got what they deserved. Tales of Port Royal’s rowdy inhabitants were well known throughout the Atlantic world. John Taylor, who visited Jamaica in 1687, explained that Port Royal was “verey lose in itself, and, by reson of privateres and debauched wild blades wich come hither.” The city, he continued, “‘tis now more rude and anticque [i.e. antic] than ‘ere was Sodom, fill’d with all maner of debauchery.” The 1692 earthquake was seen as God’s divine judgment on the people of Port Royal. Pamphlets published in the wake of the earthquake reinforced this sentiment. A local minister who had hoped “to keep up some shew of Religion among a most Ungodly Debauched People,” explained that the town “had much the greatest share in this terrible Judgment of God.”

The merchant Lewis Galdy was among the multitude of people unable to escape the “Judgment of God.” He, like thousands of his fellow townsmen, was “swallowed up by the Great Earthquake.” But, in a bizarre turn of events, he lived to tell the tale.

At 11:42 am, on June 21, 2014—324 years and two weeks after the famous earthquake devastated Port Royal—I found myself walking along the sandy cay that was once home to British America’s second most populous city. My dissertation on early modern Caribbean cities had led me to Kingston, where I was researching in the National Library of Jamaica and the Department of Archives. Curious to see the wickedest city in the west (or at least its remnants) for myself, I took a cab to Port Royal one Saturday morning. After ten or so minutes of driving through Kingston, my cab driver soon turned onto a coastal road that took me alongside the Kingston Harbor and then onto the Palisadoes Spit, a narrow strip of land that separates the harbor from the sea. Gazing out the taxi window to my left, I could see the waves of the Caribbean Sea crashing down on a man-made rock wall. To my right, the calmer waters of Kingston Harbor were dotted with fishermen and container ships. Ten minutes and seven miles later, I found myself at the end of the road. There lay the sleepy fishing town of Port Royal.

I asked my cab driver to drop me off in between a small cruciform church and a soccer field. I could see Fort Charles, the only remaining seventeenth-century structure, just ahead. I decided to take a tour.

A guide greeted me at the fort’s ticket booth and ushered me around the property. She recounted the history of the fortification, pointed out the former prison (now a bar), and showed me the buoys located a ways offshore that marked the pre-1692 coastline of the city. I asked her about the church I had seen on my arrival. Curious about the unassuming white church I had been dropped off beside, I began badgering the tour guide. Was it worth visiting? Was it open? When was it built?

My guide encouraged me to stop by the church before making my way back to Kingston. The first church built on that location met its fate in the 1692 earthquake. The next church was built in 1703, but it was badly damaged by a series of hurricanes. The present-day St. Peter’s Church was completed in 1726. Though it was unlikely to be open, she assured me that there was at least one site worth touring.

And that’s when I heard the story of Lewis Galdy, the man who was buried twice.

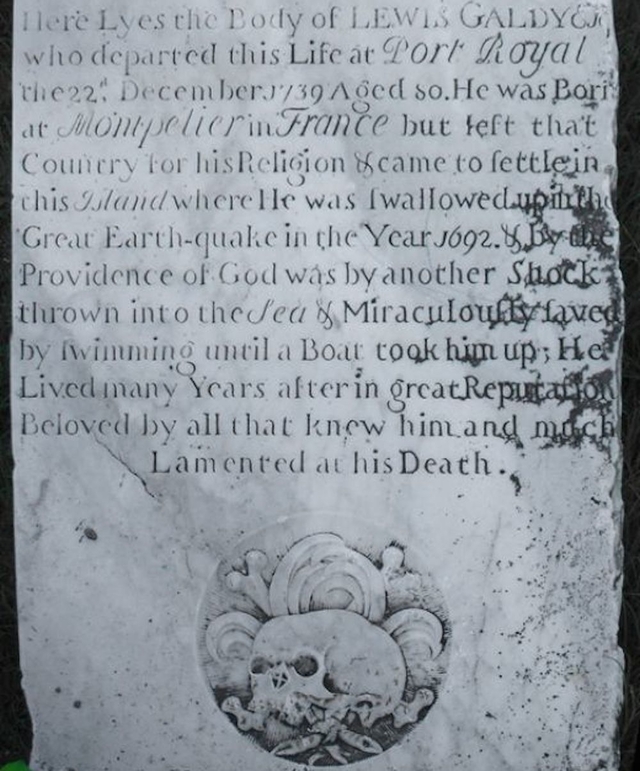

In a small graveyard in front of St. Peter’s Church, a tombstone recounted the most miraculous tale. Galdy, despite the ridiculous odds, did not die when he was “swallowed up by the Great Earthquake.” No, in fact, he lived for another 47 years. His tombstone, engraved with a crest and a skull, boasted the motto, “Dieu Sur Tout” (God Above All). The grave marker also narrates the story of his survival. It reads:

Here lies the body of Lewis Galdy who departed this life at Port Royal on December 22, 1739 aged 80. He was born at Montpelier in France but left that country for his religion and came to settle in this island where he was swallowed up in the Great Earthquake in the year 1692 and by the providence of God was by another shock thrown into the sea and miraculously saved by swimming until a boat took him up. He lived many years after in great reputation. Beloved by all and much lamented at his Death.

Lewis Galdy lived in a world of wonder, where an earthquake could be conceived as a divine event. Yet, Galdy’s own survival stood as a testament to God’s power. For it was only by the “providence of God” that Galdy was “miraculously” saved. For those living in the early modern period, God’s judgment not only dictated death; it also enabled life and dispensed grace.

Though most colonists relocated to Kingston in the wake of the earthquake, some fishermen and merchants remained on the sandy cay. Galdy was one of them. He continued working as a merchant in Port Royal where he dabbled in commodities including wine, cocoa, and slaves. He even pursued pirates off the coast of Jamaica at the behest of the governor. In his last few decades, he dedicated his public life to rebuilding Port Royal’s church. He served as one of Port Royal’s assemblymen as well as a parish churchwarden. In fact, it was Galdy who oversaw the construction of St. Peter’s Church in 1726.

Though some fishermen and merchants remained on the sandy cay, following the earthquake, the town never possessed the same vibrancy it had fostered in the last half of the seventeenth century. Today, the town is a sleepy place, animated by a few hundred locals, one hotel, and a seafood restaurant named Gloria’s.

But while Kingston never regained its position as a city, it endured through what English colonists would have seen as two acts of God’s providence—the earthquake that destroyed the Sodom of the West Indies, and the other aftershock that regurgitated Galdy. Perhaps the Caribbean’s wickedest city was not hopeless. Perhaps it could be redeemed after all.