The Hawaiian Invasion

Confronted by imperial aggression, Hawaiian musicians developed a distinctive playing style that had a profound impact on twentieth-century musical culture.

On January 16, 1895, Queen Liliuokalani, Hawaii’s last monarch, was arrested and imprisoned in a bedroom on the second floor of the Iolani Palace, the kingdom’s historic seat of government. She was charged with treason for alleged involvement in an abortive counter-revolution attempted by royalist supporters several days prior. These conspirators hoped to restore Liliuokalani to the throne from which she had been deposed two years earlier, in a coup conducted by a group of mostly American citizens whose ultimate goal was the annexation of the Hawaiian islands to the United States.

Apart from a humiliating trial, the queen was confined to that forlorn room for eight months. Although she was initially not permitted to have newspapers, Liliuokalani must have suspected fairly quickly that her people’s struggle for political sovereignty was irretrievably lost. Three years later, in a decisive victory for American political and business interests, Hawaii was formally annexed to the U.S. over the objections of a majority of the native population.

To soften the sting of solitude, the queen turned to musical composition, her “usual solace in either happy or sad moments.” She recalled that “hours which I might have found long and lonely passed quickly and cheerfully by, occupied and soothed by the expression of my thoughts in music.” Like many of her royal ancestors, Liliuokalani loved music. It was during her house arrest that she transcribed what was to become her most popular song, “Aloha Oe” (Farewell to Thee). In the languor of her captivity, the tune, originally inspired by an affectionate farewell between lovers, became a lament of dispossession.

Confronted by imperial aggression and commercial hegemony, future generations of Hawaiian musicians were able to offer their erstwhile queen at least some degree of consolation.

The primary weapon of the Hawaiian invasion was the steel guitar. Many have taken credit for its invention, and it is possible that the technique of noiselessly sliding a piece of glass, steel, or bone across the strings of a guitar developed independently, multiple times: a convergence in music technology. Nevertheless, the story of the native Hawaiian Joseph Kekuku has emerged from music history’s apocrypha as the best documented and accredited case. After a teenage Kekuku’s alleged seven years of privately perfecting his method in the 1880s and 1890s, it swept the islands and then worked its way to the mainland.

In the early years of the 1900s, the seductive, evocative sound of the steel guitar drifted over the ocean and astonished American audiences. The first generation of Hawaiian players, including Kekuku, Ernest Kaai, Ben Hokea, and Pale K. Lua, toured the States and Europe, buoyed by their virtuosity. They established reputations so strong that some of them never returned to Hawaii. The “foreign” musical import began to gain a major foothold in the U.S. and interact with contemporary currents in American music like ragtime and early blues.

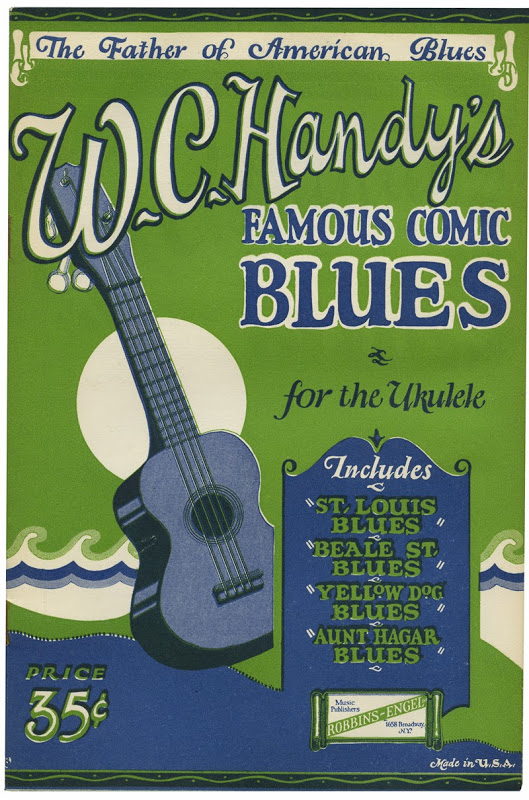

Although the new Hawaiian sound was circulating on vaudeville tours and a limited number of recordings before the early 1910s, it was the 1911 theatrical production of a Broadway play, The Bird of Paradise, that truly piqued national interest and catapulted players like Kekuku into international fame. The show, an otherwise hackneyed love story between an American military man and a Hawaiian lass, highlighted a quintet of Hawaiian musicians playing steel guitar and ukulele. A New York Times review was not alone in lauding its “introduction of the weirdly sensuous music of the island people.” Imitation plays sprang up and companies released recordings and sheet music of Hawaiian songs to capitalize on its immense success.

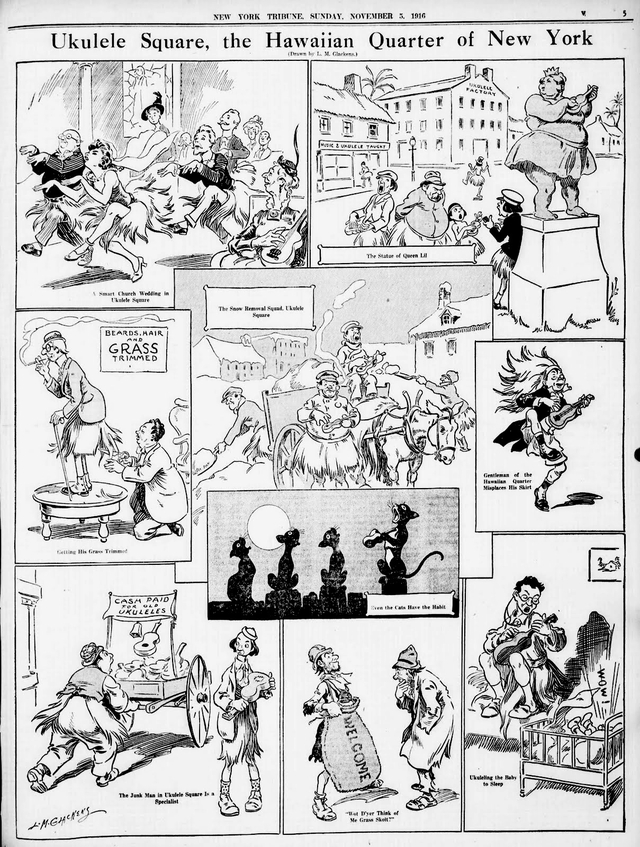

A cartoon satirizing the ukulele craze by Louis M. Glackens in the New York Tribune, Sunday, November 5, 1916. Wikimedia Commons

Universal expositions and world fairs in the first two decades of the twentieth century also served as important vehicles for the presentation and popularization of Hawaiian music. The most extravagant and well attended of these was the Panama-Pacific International Exposition of 1915 in San Francisco, which escalated the Hawaiian sound into a bona fide national obsession. A member of the Hawaii Promotion Committee said that the islands’ pavilion at that exposition was intended to render them “the tourist mecca of the travel world.” He boasted that it was “the best-known building” at the exposition and a “colossus in popularity, for the strum of ukuleles and the tinkle of guitars gently touching passers-by, compelled entrance to the building.”

The exposition did elevate Hawaii’s touristic cachet. But it also allowed native performers to tour the mainland. As curious visitors to the exposition were “lured by the ear-haunting melodies of the Hawaiian musicians,” increasing numbers of native performers were likewise drawn into the commercial riptide and deposited far from home in American studios and stages.

By the 1920s, the channels through which Americans accessed new music were expanding. The plaintive call of the steel guitar permeated the country through records, movies and radio transmissions as well as live performances and traveling shows. Many of the nation’s leading country and blues musicians drew inspiration from Hawaiian steel. A young and ambitious Jimmie Rodgers, before he had earned his title as the “Father of Country Music,” pooled his cash earned from performances on a traveling show to create his own “Jimmie Rodgers Hawaiian Tent Show.” Country player Bob Dunn, later a pathbreaker in electrical amplification, watched a Hawaiian stage show in Eastern Oklahoma at age nine and took up the steel guitar soon afterward. Jerry Byrd, renowned pioneer of the Nashville sound, had a similar epiphany at thirteen when he witnessed a Hawaiian troupe touring during the Depression. Influential bluesman Oscar “Buddy” Woods imitated the Hawaiian guitar style that he observed during a show in the early 1920s. Troman Eason, early innovator of the “sacred steel” gospel tradition, became hooked after hearing a Hawaiian play it over the radio in Philadelphia in the mid-1930s.

One could speculate that the vocal-like quality of the slide technique was attractive to early country musicians who had previously used instruments like the fiddle and harmonica to imitate the human voice. The first country performer believed to have recorded a steel guitar on his lap in the established Hawaiian style was a West Virginian coal miner named Frank Hutchison, who cut two songs, “Worried Blues” and “Train that Carried the Girl from Town” in 1926. Jimmie Rodgers would record thirty-one songs featuring the steel guitar during his career (and play ukulele on one). Maybelle Carter of the celebrated Carter Family converted her guitar to a “Hawaiian setup” in 1928. The first ensemble to be labeled on a record as “hillbillies,” a collection of string musicians from North Carolinian and Virginian counties, made early use of the steel.

The instrument’s Pacific origins found acknowledgement in the names of 1920s Southern string bands like the North Carolina Hawaiians. Some of these early roots groups performed renditions of traditional Hawaiian tunes in a prefigurement of the modern “cover version.” Examples include the Scottsdale String Band’s version of “My Own Iona” and the Shamrock String Band’s rendition of “High Low March,” most likely a simultaneous adaptation and mispronunciation of the earlier Hawaiian recording, “Hilo March.” Early cowboy bands would assume different identities for consecutive gigs, performing one night under a name like Hawaiian Troubadours and the next as Barn Dance Troubadours. The distinguished country songwriter Ted Daffan only needed one steel guitar to play in a Hawaiian-themed group called the Blue Islanders in 1933 and a country ensemble called the Blue Ridge Playboys the next year. Eminent steel guitarist Herb Remington moved with ease in the other direction, from the Texas Playboys to his Hawaiian group, the Beachcombers. This sonic shapeshifting was both an effect and cause of the blurred lines between distinctly Hawaiian music and the nascent folk forms ripening in the U.S. during this time.

Banjo ukelele emblazoned with the words “Jesus Saves,” from a 1936 postcard from Pennsylvania. Jim Linderman

The Hawaiian influence upon African-American blues musicians is evident as well, although it demands more careful historical scrutiny as some sort of sliding technique on guitar may have been invented independently by black players. W. C. Handy, the “Father of the Blues,” recalled the “unforgettable” effect of seeing a man in 1903 pressing “a knife on the strings of [a] guitar in a manner popularized by Hawaiian guitarists who used steel bars.” Some scholars have argued that the early blues technique of sliding a knife or broken neck of a bottle against guitar strings may have roots in an African instrument, a single-stringed musical bow. Significantly, most blues players of the era held their guitars in the upright position, in contrast to the Hawaiian style in which the instrument is rested on the performer’s lap.

Nevertheless, the seminal bluesman Charlie Patton played in both styles. A set of blues guitarists in the 1930s, including Kokomo Arnold, Casey Bill Weldon, Oscar Woods, Tampa Red, and Black Ace adopted the Hawaiian style and incorporated the Hawaiian practice of playing long melodic lines, as opposed to a blues style defined by short, staccato riffs. Casey Bill Weldon was advertised on some of his recordings as the “Hawaiian Guitar Wizard.” B. B. King has credited Hawaiian steel guitar as an influence, particularly Bukka White, who played in the Hawaiian style. Legend has it that White gave B. B. his first guitar. When Elmore James recorded his composition “Hawaiian Boogie” in the early 1950s, he concurrently paid homage to the music that had inspired the previous generation of bluesmen and illustrated how far the blues had come from its humble origins.

Casey Bill Weldon - “I Believe I’ll Make A Change”

For the historian tracing the genealogy of the American roots idiom in the first few decades of the twentieth century, these examples reveal some part of the dense web of influence spun by Hawaiian sounds. Quantifying this influence appears to be difficult, if not impossible. The historian could perhaps content herself with the impressionistic conclusion that some of the many ears that heard Hawaiian songs on the mainland were inspired, consciously or unconsciously, to appropriate stylistic or instrumental elements into their own music.

In reality, the narrative of the Hawaiian invasion is not simply one of abstract inspiration via radio waves and traveling circuses. It is equally a story of personal interaction and musical communion between Hawaiian immigrants to the mainland and American performers.

Some of the best-known first-wave Hawaiian guitarists would never return to the islands, instead settling down in major mainland cities to open music studios and teach. Kekuku did so in Chicago and then Detroit, Walter Kolomoku in New York, and Ben Hokea in Toronto and Ottawa. Ernest Kaai moved to Miami to establish a music store and studio, where a small colony of Hawaiians had sprung up as a result of its tropical climate and setting. American companies seeking to capitalize on the popularity of the steel guitar and ukulele made sure to advertise that their lessons were offered by “native” Hawaiians. Even during tours and expositions when their services were in high demand, these musicians would give lessons to inquiring Americans. Kekuku remained in Seattle for some time after the Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition of 1909 to teach steel guitar, and some of his students there went on to become musicians and music teachers themselves. George E. K. Awai, the leader of the Hawaiian troupe that performed at the Pan-Pacific Exposition, stayed behind in San Francisco afterwards to teach ukulele and steel guitar, and to publish instructional manuals for the instruments.

Jenks “Tex” Carman, the “Dixie Cowboy,” was mentored by Frank Plada, one of the first Hawaiian musicians to come to the States. Carman’s song “Hillbilly Hula” provides an alliterative example of the cross-cultural fusion that defined much of nascent country music. Hawaiian virtuoso Bennie Nawahi’s curiously-named band in the 1930s, King Nawahi and the International Cowboys, featured a young Roy Rogers before he became a cowboy phenomenon. Bob Dunn took steel guitar lessons for several years through correspondence with Walter Kolomoku, who had first gained fame on a Bird of Paradise tour. Renowned Nashville steel player Buddy Emmons enrolled in the Hawaiian Conservatory of Music in South Bend, Illinois, as a teenager. Troman Eason was so enamored of the steel sounds emanating from his radio that he arranged for lessons with their source, one of two brothers who came to the States to teach at the Honolulu Conservatory of Music in Philadelphia.

In addition to these pedagogical associations, professional and collaborative partnerships arose between these musicians. Vernon Dalhart, a major influence on the development of country music, produced his first recording of the style with the accompaniment of native Frank Ferera’s steel guitar. Rodeo star and actor Hoot Gibson brought the guitar maestro Sol Hoopii from the islands to Hollywood in the early 1920s to play in a cowboy band. Rodgers recorded sessions on separate occasions with three Hawaiian guitarists. Nawahi played with a group of black musicians, the Georgia Jumpers.

Jimmie Rodgers’s 1929 cut of “Everybody Does It In Hawaii” offers an illustrative example of the genre-bending ethos of this period. The lyrics, indulging a miscegenational fantasy with the islands, are not particularly noteworthy. However, the music, which superimposes Rodgers’s famous country yodel over the Hawaiian Joe Kaipo’s steel guitar, seamlessly blends Honolulu and Dallas (where the song was recorded). Rodgers’s partnership with Kaipo extended to several other classics as well. The Hawaiian steel’s yearning chime feels right at home underneath Rodgers’ lonesome crooning. Soon after, Rodgers would record with Lani McIntire, who headed one of the most famous Hawaiian ensembles at the time.

Hawaiian fingerprints extended even to the technical development of the guitar. The steel guitar models of famed luthier Chris Knutsen were inspired by his contact with Hawaiian musicians and their home-made instruments at the 1909 Exposition in Seattle. George Beauchamp, an early guitar innovator taken in by the Hawaiian sound, entrusted his tri-cone prototype to the trusty fingers of Sol Hoopii, who cut a series of 1926 recordings that propelled the model into the national spotlight almost overnight. Advertisements for Beauchamp’s guitars frequently featured the endorsements of renowned Hawaiian guitarists such as Hoopii and Sam Ku West.

The guitar demanded amplification as audiences grew in the 1930s, and the quest for volume naturally bore marks of Hawaiian inspiration. Beauchamp’s “Frying Pan,” the first electric guitar ever produced, was a Hawaiian steel model. Leo Fender, inventor of his eponymous guitar and a major influence on the subsequent development of electronic instrumentation, was also an avowed appreciator of the Hawaiian sound. During the planning stages for the Stratocaster model, he recruited Hawaiian prodigy Freddie Tavares as an assistant and design collaborator. Tavares would later innovate pedals for the electrified steel guitar, enabling the extensive volume and pitch control that now define modern country music.

The national obsession with the Hawaiian sound could even be credited with reorienting the landscape of popular music around the guitar and launching its career as the quintessential instrument of twentieth-century American music. Naturally, guitars were played on the mainland prior to Hawaii’s annexation, but they served primarily to provide rhythmic and chordal backing. The Hawaiian groups of the early twentieth century transformed the guitar into a lead instrument, placing it front and center as the iconic focus of the ensemble. One scholar’s examination of guitar magazines in this period shows shifting perceptions of the instrument during this era, as musical communities found themselves divided between the older, “sophisticated” tradition of classical guitar and the new phenomenon of steel guitar. The latter’s mellifluous sounds popularized (or vulgarized, depending on one’s point of view) the guitar and advanced its availability, accessibility, and acceptability in the American musical imagination.

History, like sound, cannot occur in a vacuum. Both move so rapidly and ceaselessly that they become indistinguishable from the process of motion itself. To precisely measure the impact of Hawaiian guitar in American music is thus an impossible task. We can only chase the echoes.