The Appearance of Being Earnest

The French confidence man who took credit for what one nineteenth-century paper called “the most gigantic swindle of our time.”

It’s 1879. The courtroom in Santiago is full. The tables and benches and sidelines hold a defendant, his accomplice, the lawyers for all sides, the justice of the Chilean Supreme Court, and onlookers. The trial had dragged on for two years. The defendant was incarcerated all the while at the nearby Des Hotel Ingles. This autumn afternoon was the end of a very long journey.

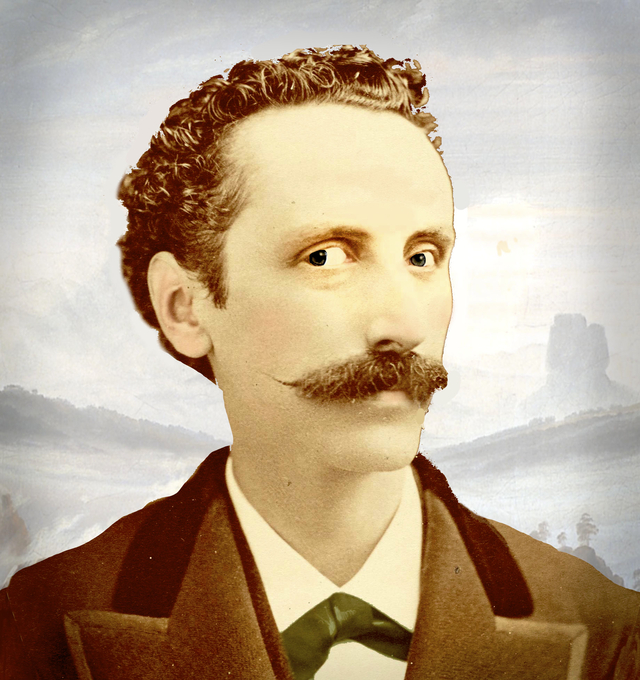

Up to that point in life, the accused had “engaged the most elegant suite of rooms in the most fashionable hotels,” charming investors with his “large, eloquent eyes.” Having spent the prior decade crisscrossing half the globe from Europe to North America to South America, he was the man papers from the United States to New Zealand called “foremost in the ranks of the world’s swindlers,” the man who they said had “the black heart of a conscienceless scoundrel,” the one the New York Times devoted ten long paragraphs to in his obituary six years later as the “king of swindlers.” He was the Chevalier Alfred Paraf.

Paraf was a Frenchman. He was born on June 10, 1844, in the Alsace region near the Rhine. He’s not part of historical memory anymore, though the image of his deceptive capacity was a stock reference in stories about swindlers for decades. He had, such sources say, a big personality and a winning smile. He had, they said, “the suave address of a gentleman.” And of course, yes, he had a wax-tipped moustache. One paper described him as a man with “the form and features of an Apollo” to match “the polished manners of a citizen of the world.” Another called him “handsome, polished, well educated, known for his keen intelligence and ready wit.” In an age of confidence men—con men—a Brooklyn daily said of Paraf that he stood “above and beyond his fellows, who, compared with him, were mere bunglers in operations which he had reduced to an exact science and of which he was the greatest…exponent.” From Alsace to Scotland to New York to Rhode Island to San Francisco to Nevada to Chile, Paraf made his name as “handsome, refined, clever, brilliant, extravagant, immoral and audacious.”

His swindle? His crime? His unconscionable deed?

Fake butter. Oleomargarine. The scourge of dairy natures.

Paraf was an adulterator. He made artificial versions of natural things and sought to pass them off as equivalent. Adulteration is the term long used to describe the contamination, deception, or false substitution of one product for another. New chemical additives for processing, preserving, and cheapening an entire range of foods; new ways to dilute milk, cheese and other dairy items; new processes for refining or creating alternatives for sugar; cheap substitutes for the grains of bread and other baked goods; thrifty uses of meatpacking by-products, with the fats and oils of cattle and hogs ending up quite far from stockyards; new supply chains that called into question the identity of the tea, coffee, spices, and liquors coming from afar.

Oleomargarine was a purported adulterant of butter. In the century to come, many would think of it as a cheap substitute for butter. Margarine’s evolution in public consciousness is so great that, rather than concealing the deception, by the later twentieth-century marketers took it as a point of pride that consumers could be tricked—they couldn’t believe it’s not butter. Yet in the decades after its invention in 1869, it would be cast instead as “the most gigantic swindle of our time.” The charges against it were serious and severe. “The Cow Superseded,” said the San Francisco Chronicle. “That atrocious insult to modern civilization,” if we follow the Washington Post. It was puzzling and complicated because it was about far more than fake butter.

Here we are then, at the dawn of the age of manufactured food. Here we are, in the midst of a century of mobility, invention, expansion, and industrial development. Confidence men, charlatans, and swindlers were at the time—and forever after—the fodder for untold numbers of cautionary tales in a changing world. Swindlers, to be sure, did not alone spawn adulteration, as there were any number of reasons why the claims about a product might differ from the reality: accidents, spoilage, natural decay, storage issues, simply losing track of ingredients. But the same questions of trust and confidence that framed the world of the charlatan set the stage where concerns and fears over deceptive or contaminated foods played out. Though Paraf was a member of an age-old class of huckster, his particular swindle was very much of its time.

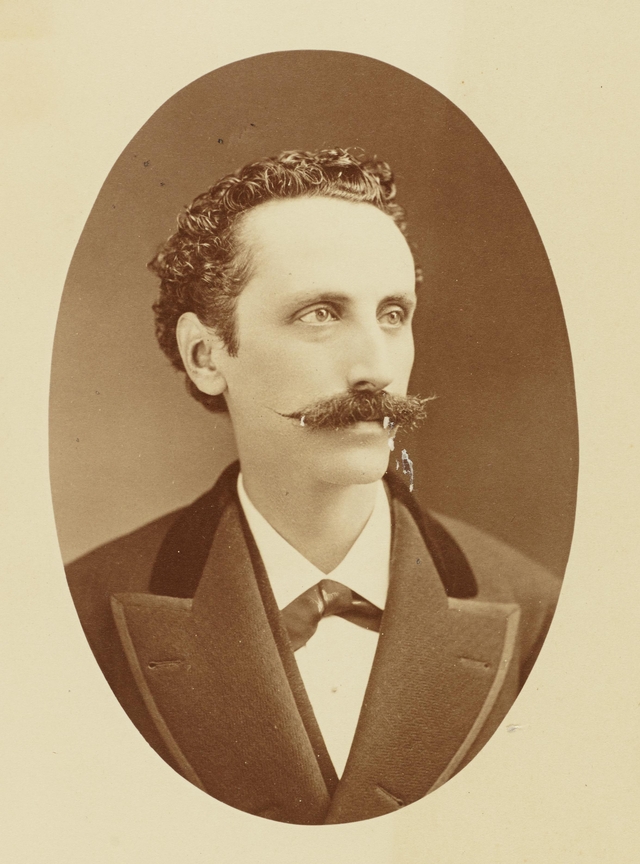

Paraf had this portrait taken while in San Francisco at the studios of Bradley and Rulofson, 429 Market Street. It accompanied the announcement of the public display at the Placard Exchange in October 1873. The guy looks good. Paraf Portrait, Charles Chandler Papers, Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Columbia University in the City of New York

The handsome Chevalier may have become famous as the proprietor of the oleo swindle, but his crimes and stature far exceeded that singular product. Likewise, while margarine may have been a particularly egregious affront to the nature of the cow—the nature of an agrarian world—it was joined by a laundry list of artificial products entering fin-de-siècle marketplaces. It was the combination of agricultural deception and cultural forgery that landed the French chemist in jail. His biography animates the larger complexities of trust and novelty in the era of adulteration.

Paraf was the son of a successful dye maker in Mulhouse, a town in eastern France maybe halfway between Strasbourg and Basel. The area was a hotbed of manufacturing development by mid-century and the seedbed for a chemical revolution over the next half century. To speak of chemistry at the time was to speak of a scientific trade devoted to animals, vegetables, and minerals. Agricultural chemistry was coming into its own, animal chemistry was thriving, and plant chemistry was an active focus for scientists, dye-makers and druggists alike. Agricultural and manufacturing efforts were often of a piece, all common stages in the exchange of organic material. Fabrics and textiles were woven in mills from the fibers of the land; colors were mixed from extracts of plants; the bulk of new foods drew from combinations of plant and animal oils and fats; and chemists served as aids to the processes.

The young Paraf’s chemical prowess began with training from his father. At age fourteen, he went to study in Paris at the Collège de France. His skills—he would have over a dozen patents before he was thirty—gave him access to a profitable trade. By his early twenties, though, he was bored and restless.

With traveling money from his generous father, he set out in the early 1860s for Glasgow. It was there that his chicanery began. Having quickly lost his cash on ostentatious living, he devised and sold a new calico dye from a fragrant plant called weld (reseda lutea). The color, it happens, wore off after minimal use. That wearing off was long enough after its application for Paraf to hightail it back to France before he was caught. He was there just long enough to bilk his own uncle of thousands in another scam before crossing the Atlantic to New York in 1866 or 1867 (reports differ), a spry 23-year-old.

Paraf blossomed in Manhattan. He met, courted, and wed Leila Smith, the daughter of a high profile New York lawyer. He took side trips to New England to advance his dye-making funds, at one point fleecing the former Governor of Rhode Island out of tens of thousands. He lived lavishly in midtown Manhattan and dined at only the most posh houses, Delmonico’s among them. He launched a new manufacturing facility with a pilfered patent. Paraf had a lot going on: a wife to woo and marry, a new industry to start, patents to file, appearances to keep up, investors to dupe, creditors to flee. Here was a man on the move.

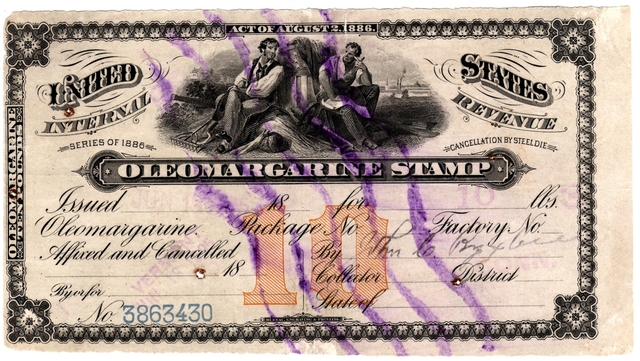

An early tax stamp for oleomargarine from the later 1800s. http://usrevs.blogspot.com

And he moved quickly—not just geographically, but in business dealings too. Because he was a learned man and a notable chemist cutting a suave figure, Paraf identified and then collapsed the cultural distance between the unknown and the trustworthy. He filled that new historical space with metrics of confidence and the veneer of respectability and allure. (Can I conjecture that women wanted to be with him and men wanted to be him?) In fact, had he been “only a brilliant swindler, obtaining gold and silver from old boots and creating fortunes out of the refuse of tar barrels,” wrote the Brooklyn Eagle, “the world would have been content to let him squander the money he acquired so easily without grudging him his meteoric prosperity or demanding his punishment.” But no, while the American people may have borne “forgery, defalcation [and] hypocrisy,” what he did was “an act too base for characterization.” It was, his advocates would write, “the crowning work of his active intellectual life.” “What he did,” his detractors would shout, “was to introduce oleomargarine, a vicious substitute for butter.”

What he did was to compound worries over the artificial. He claimed the patent for oleomargarine as his own. He’d nabbed it from his fellow Frenchman, Hippolyte Mège-Mouries. The Mège Patent, as it was later called, had been motivated by the coming Franco-Prussian War of 1870. As early as the 1867 World Exposition in Paris, Napoleon III was encouraging animal chemists to develop a cheaper substitute for butter, all the better to save important milk and dairy stores for the troops. Mège mixed milk with heated and refined animal fats—tallow from rendered beef suet, for its stearin and olein—to reduce the dairy content of butter. A new product was born. Paraf thus misrepresented his relationship to the invention of a product that people feared was a misrepresentation of natural butter.

Stolen recipe in hand, Paraf charmed investors to establish the Oleomargarine Manufacturing Company in 1873. While maneuvering to start the company, he took meetings with the eminent (though undoubtedly less suave) chemist Charles Chandler. Chandler, a professor at Columbia’s School of Mines (1864), the first chemist of the newly chartered New York Board of Health and its Anti-Adulteration Division (1866), and a founding member of the American Chemical Society (1876), dismissed the young man as a curiosity without much comment. Some later reports claimed that Paraf had “studied with Chandler” while in New York. If so, the things he studied were not academic.

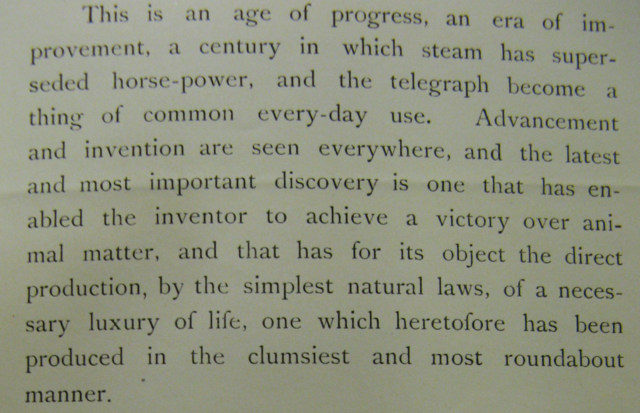

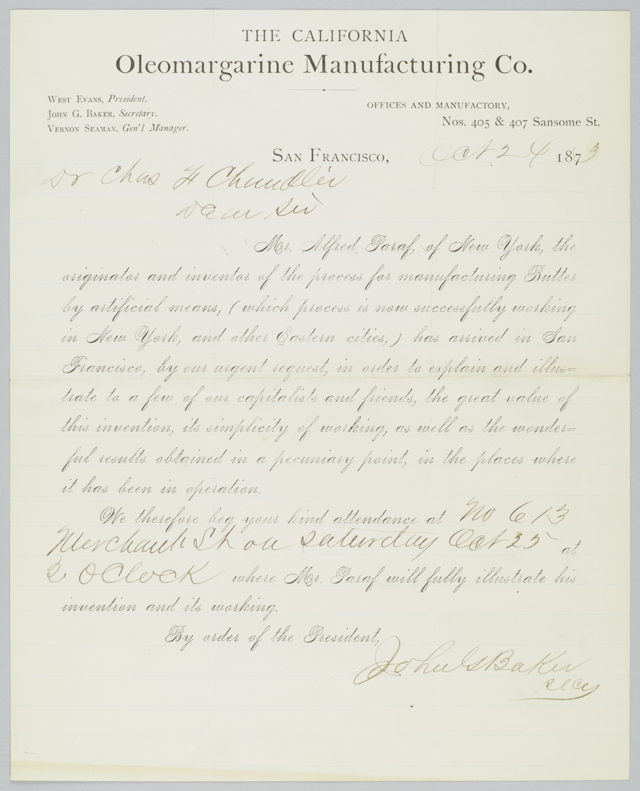

This is part of an invitation posted to the public to advertise Paraf’s public demonstration of the process for making oleomargarine on October 25, 1873. California Mail Bag, October 23, 1873

Paraf stayed a step ahead of those who would question him by heading west later in 1873. Ostensibly at the invitation of capitalists in California, he helped build the new California Oleomargarine Company in San Francisco. In a show meant to cull public trust, the company hosted a demonstration of the process in October. The public display is a hallmark maneuver of con men; it isn’t a big step from Paraf’s margarine to Barnum’s circus to the carnival of historical tricksters engendering trust through purportedly transparent demonstrations. The invitation was published in local papers and publicized in formal letters to prominent figures, Prof. Chandler in New York among them. Included with the invitation was a glossy biography of the handsome Chevalier. (It also included the fetching studio portrait above.) The text matched the image. The biography painted a picture of unsullied character and inventive prowess.

Secretary John Baker of the Oleomargarine Company of California formally invited Professor Charles Chandler of the Columbia School of Mines to attend a public display by Paraf, where the chemist would “fully illustrate his invention and its workings.” It’s a strange letter, noting an event to be held October 25 but sent from San Francisco to New York only the day before. It also appears to be a form letter, with the addressee and date filled in as suited to the occasion. Announcement of Public Display, Charles Chandler Papers, Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Columbia University in the City of New York

This too: as he traveled to San Francisco, his investors back east had found that he stole—“filched,” they said—Mège-Mourie’s invention. They dispatched representatives to Paris, securing the rightful use of the Mège Patent. Upon return, they renamed and reorganized the venture as the United States Dairy Company. A new name and constitution would distance themselves from their ill-gotten founding.

All the while, news traveled quickly along the telegraph lines strung beside the same new rail lines that brought Paraf west. The Chevalier was arrested in California with an associate on August 4, 1874, “under an indictment for forgery.” Bail was set at $10,000.

It didn’t dissuade him. He of the eloquent eyes spent more than two more years in California, leaving no record that the trouble back east was a matter of concern nor the forgery arrest something to take seriously.

Then he was off again, this time to South America, landing near Santiago, Chile, with his personal servant in tow.

Chilean authorities detained and questioned Paraf upon his arrival in 1876. His reputation had preceded him. A Peruvian paper later reported that he, “a notable chemist,” had arrived in Chile with “a brother and six family members” and “the supposed discovery he has made.” His family was certainly not with him. Paraf, it seemed, had himself a little entourage. It also isn’t clear which “supposed discovery” the story referred to, though we do know he would soon apply to the Minister of the Interior for patent protection to transform animal fats into olein and stearin. The olein would help his margarine cause. Stearin led him to soap and candle making and, more compellingly for investors, the glyceride that would provide an ingredient in smelting, bullet casing manufacturing, and gunpowder production. (Stearin is a glycerin. Nitroglycerine was produced from glycerin and nitric acid. Was Paraf planning to arm revolutionaries of South America? I have no evidence of it, but the image is compelling.) Always the dignified con man—poised, confident, dashing as ever, appearances first, please—he made it past the interrogation to settle in for that set of new projects.

It’s here that Paraf, known to the public as having “distinguished himself in oleomargarine swindles,” met his final demise. For this confidence man, it appears, finally, that “over-confidence was his ruin.” He had accrued too many false fronts in too many places. A retrospective observer (I’ll volunteer) might have said, Mr. Chevalier, you’ve got to know when to stop. Alas, I wasn’t there.

In his time awaiting trial at Des Hotel Ingles on the Pacific coast of South America, he saw a pamphlet circulated to highlight his biography and dismiss the purportedly scurrilous charges from the United States and Europe. At one point he sought to delay the proceedings to await the arrival of his family. He said his wife, then in Bordeaux, was on her way. There was no word if his young son was in tow. He had also somehow persuaded a naive Chilean to support his mining venture to turn tin into gold with some of those new animal fat inventions. Locals in fact erected the Paraf Smelting Works, an edifice that upon his conviction stood as “a monument of the folly and gullibility of the Santiago public.”

The court would put him away for good in October of 1879, guilty of violating Articles 167 and 468 of the Chilean Penal Code. He was exiled from Santiago and sentenced to five years under guard in a new penal colony 1000 kilometers south at Valdivia. Although his sentence for violating laws of public trust, forgery and falsification was for five years, he remained incarcerated for six until his death of pneumonia in 1885.

RIP, Monsieur Paraf.

Writers typically describe the era of adulteration as a consequence of new patterns of mobility, expansion and urban-rural shifts. “As soon as there emerged a consuming public, distinct and separate from the producers of food,” writes food historian John Burnett, “opportunities for organized commercial fraud arose.” This is to say that a “distance equals adulteration” equation holds sway. The distance that came from movement begot distrust, where the ever-shifting traffic of goods, people, and ideas made it tricky to establish credibility. Some, like Paraf, capitalized on that trickiness by manipulating modes of trust. They developed strategies. Public displays, for example. Or the performance of respectability and allure.

But movement and distance form only one axis of a multi-dimensional problem. The difficulties of trust arise through the tension between surfaces and depths, too, not just the movement between proximity and distance, near and far. There are metaphysics at play here. Do you trust everything someone tells you? Look inside. Dig deep. When you look them in the eyes, what are you trying to see? How do you judge a claim’s plausibility—and better yet, its truth?

So it was for those who met the dashing Chevalier. Some were taken in. Others came to wonder, is this guy for real?

Maybe it wasn’t hyperbole, maybe Paraf really was foremost in the ranks of the world’s swindlers. Not only was he conning people, but his con was a con. This fake butter, itself an adulterant, was an affront to accepted social and agricultural norms. It was produced in a factory, not on a farm. Consumers couldn’t see the connection between the dairy barn and the spread on their plates; in that, something didn’t sit right. They were thus leery of sellers masquerading margarine as butter—the real thing. They wanted “the genuine article.”

But Paraf too was not the genuine article. He too was masquerading. Not just a matter of trans-continental movement, his was a sleight of hand in surfaces over depths. Appearances mattered above all. And to us his appearance sits on a pivot in the history of nature, artifice, and food. It’s a pivot that begins with the novelty of manufacturing food and leads to its twentieth century industrialization. Even now, in the twenty-first century, we’re still questioning how we can trust our food.

This “king of swindlers” with “the suave address of a gentleman”? What exactly does that look like to us? That’s the appearance of industrial modernity. That’s what a century of confusion over the natural and the artificial looks like.