Silent Film Killed the Clown: Recovering the Lost Life and Silent Film of Marceline Orbes, the Suicidal Clown of the New York Hippodrome, 1905-1915

The tragic fate of the Spanish comedian who inspired Chaplin. Vintage French postcard (“L’amour de Pierrot,” c. 1905), via Wikimedia Commons

In his hotel room he got out the photographs that had been taken of him years ago. Marceline himself had to smile a little at those merry mocking faces. Then, at four o’clock in the morning, he reached for his revolver and shot himself. His body slumped down by the bed on which the photographs were spread out.

—TIME Magazine on the death of Marceline Orbes

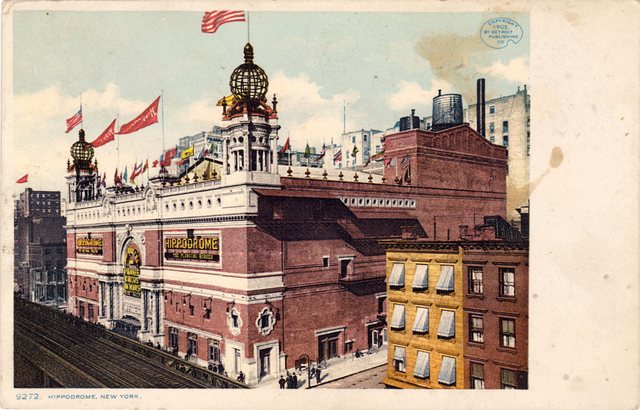

The name Marceline Orbes is an obscure one today. But to Charlie Chaplin, the auteur of early cinematic comedy, it was deeply significant. Marceline, as he was generally known, was one of the superstar clowns of the trans-Atlantic stage, appearing for five years at the Hippodrome in London, from 1900 to 1905, before embarking on a stunning ten-season residency at the New York Hippodrome. By 1915, Marceline had established himself as one of the western world’s most popular comedians. He was also one of the most influential.

Whilst in London, in 1901, Marceline, during an elaborate production of Cinderella, worked with a young Chaplin. Over sixty years later, Chaplin would describe Marceline’s act in vivid detail:

Marceline, the great French [Spanish] clown, dressed in sloppy evening dress and opera hat, would enter with a fishing rod, sit on a camp stool, open a large jewel-case, bait his hook with a diamond necklace, then cast it into the water. After a while he would ‘chum’ with smaller jewelry, throwing in a few bracelets, eventually emptying the whole jewel-case. Suddenly he would get a bite and throw himself into paroxysms of comic gyrations struggling with the rod, and eventually pulling out of the water a small trained poodle dog, who copied everything Marceline did: if he sat down, the dog sat down; if he stood on his head, the dog did likewise.

Chaplin gave little credit and, as historian Bryony Dixon argued, seemed reluctant to share the inspiration behind his own brilliance. In his autobiography, however, Chaplin dedicated a remarkable amount of space to Marceline, an indication of the esteem in which he held the clown’s now-lost comedic genius.

Despite Chaplin’s respect and admiration, Marceline’s artistry has been the subject of remarkably little scholarship or study. Decades after his death, Buster Keaton would remember Marceline fondly as the “greatest clown.” No mean feat. Unfortunately for historians, pop culture scholars, and circus enthusiasts, Marceline’s work occurred almost exclusively in a live, theatrical setting—almost nothing of it survives to be appreciated and studied today. Even Mishaps of Marceline (1915), his sole foray in the world of narrative film, has been lost. Marceline deserves much more recognition than he has received.

A Clown Rises

Marceline Orbes was born around 1873 or 1874 in Saragossa, Spain, to a large family. Struggling financially, young Marceline was allowed to appear in a local circus performance:

The child dressed as a miniature replica of the man [clown] who carried him, was set down in the middle of the sawdust ring and tumbled about to the amusement of the crowd. He became an acrobat, a tumbler, training his muscles so that they expressed every emotion.

Following his circus debut as an infant, Marceline, “as soon as he was old enough to choose for himself” set out on the path to become a professional august, performing in his native Spain, France, and, by the end of the century, Britain.

Emotion was a key part of Marceline’s artistry. Unlike Francis “Slivers” Oakley, his later collaborator at the New York Hippodrome, Marceline never considered himself a clown but an august:

I am funny without the clown costume, which is an art. I have never worn anything except a dress suit. I have never had the chalky face, the cap, the baggy pantaloons with ruffles which make the circus clown. I am a comedian.

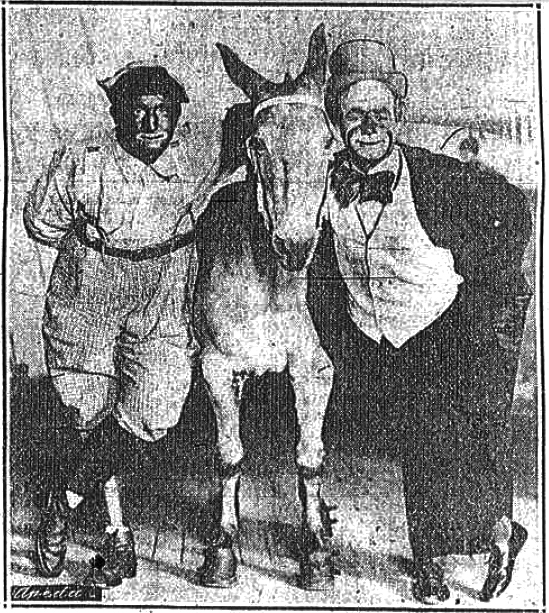

Henry Van Cleve, Pete, and Marceline (left to right), c. 1910. New York Daily Bugle, July 27th, 1912, p. 27

Another description of Marceline’s unconventional costume seemed to confirm the details. An august was “the name given to those clowns who do not wear the familiar baggy platoons with ruffles and exaggerated polka dots, but who rely upon misfit clothes as a costume to extract laughter from an audience.” That costume certainly made an impression on the eleven-year-old Charlie Chaplin who performed with Marceline at the London Hippodrome. According to Chaplin, Marceline wore “sloppy evening dress and opera hat,” a description which, as film critic David Robinson noted, mirrors Chaplin’s own famous screen garb—the clown meets the tramp. Both Marceline and Chaplin combined the raiment of gentility with farcically bad tailoring to hint at their characters’ absurdity; both comedians also worked, principally, in the realm of silence, utilizing mime through choice or technological necessity. Marceline’s makeup painted a middle ground between the traditional, Joseph Grimaldi-esque circus clown and Chaplin, eschewing the “chalky face” of his peers to accentuate the eyes and mouth and the emotions they conveyed.

By 1900 he had refined his craft to the point where he was hired for a five-season run at the London Hippodrome. Marceline’s career took another forward leap when he made the trans-Atlantic crossing to take up a ten season residency, starting in 1905, at the New York Hippodrome, a gargantuan venue in which circus-style spectacles were regularly staged for adoring crowds. Playing to audiences five thousand strong, Marceline was seen by a young Buster Keaton alongside several hundred thousand other children and their families—Marceline’s total audience over that period could potentially have numbered in the millions. The only other clown who could boast a comparable reach was “Slivers” Oakley.

He committed suicide in 1916.

In Limelight (1952) Chaplin explored the life of a former clown whose career had come to an inglorious end thanks to the apathy of his once adoring audience. Compare Chaplin’s costume in this scene with the above photograph of Marceline. Charles Chaplin and Claire Bloom, Limelight. Directed by Charles Chaplin. Los Angeles: United Artists, 1952

A Clown Falls

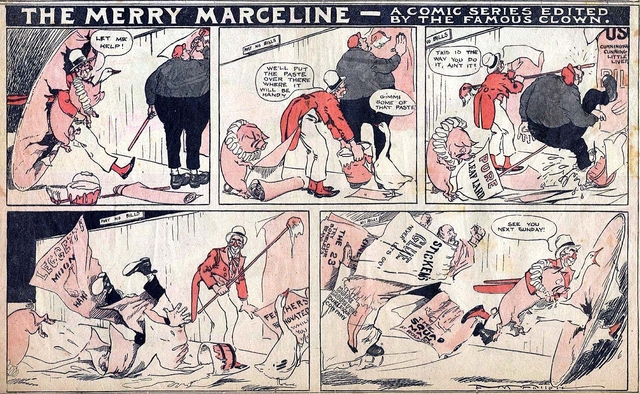

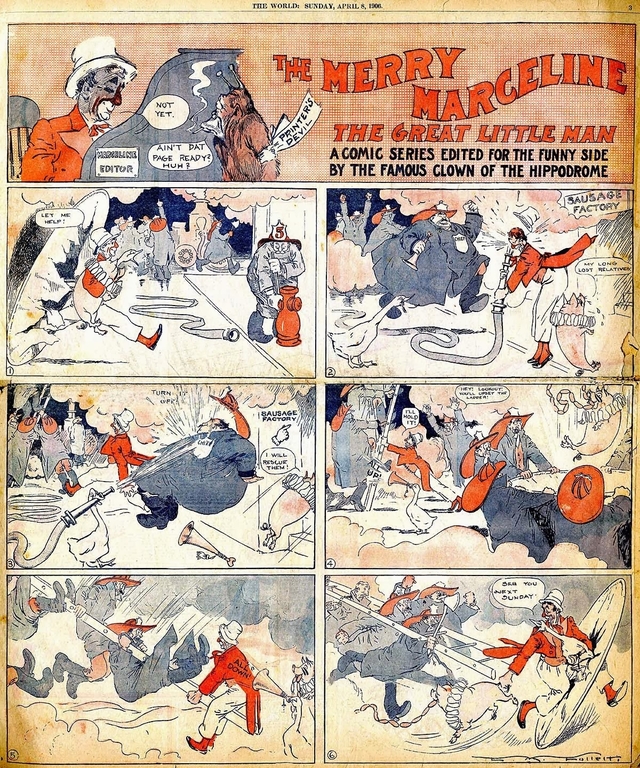

Marceline’s name appeared regularly in the papers—“World Famous Clown,” “A master of pantomime,” “the Great Clown,” and “The World’s Greatest Clown” were phrases that defined his media profile. On his thirty-seventh birthday he was deluged by three thousand enthusiastic children who each shook his hand, wished him many happy returns, and attempted to guess his age. Those who did so successfully received a signed photo of the “famous Hippodrome clown.” Aside from having been exposed to Marceline through performance, traditional newspaper reporting, and strong word of mouth, they may well have read about Marceline’s fictionalized adventures in the newspaper comic which briefly appeared in the New York World. According to the strip’s by-line, it was edited by Marceline himself, though there is little indication what, precisely, that role entailed—if indeed it meant anything at all. Regardless of Marceline’s level of involvement in his own comic, the strip existed, a testament to his broad appeal.

The following year his popularity was further underlined when Winthrop Pictures released Marceline, the World Renowned Clown of the N.Y. Hippodrome, though little is known of that now-lost film. If the surviving film Dancing Boxing Match, Montgomery and Stone produced by Winthrop that same year, and held by the Library of Congress, is any indication, Marceline’s cinematic debut would likely have been little more than a single routine filmed by a lone, stationary camera featuring no narrative. It is possible that the entire film would have lasted no more than a few seconds.

At the end of a ten-season run, Marceline and “Slivers” Oakley, were the two superstar clowns of the New York Hippodrome; by 1914, Marceline was ready to advance his career once again. Marceline spent a six-month engagement in London—where he first found fame and prestige—before making his return to the US. Once back in America, he worked with Thanhouser Pictures, one of the east coast’s most prolific film studios, on his first (and only) narrative film, Mishaps of Marceline, a one-reel picture which featured the titular character, cast as a window cleaner, causing disaster wherever he went. The film does not appear to have done particularly well—no sequels or further adventures starring Marceline were ordered following its March 7th release. Though it was reported, in the March, 1915 issue of Variety, that “A deal is underway whereby Marceline, the famous Hippodrome clown, may become a member of the Keystone forces,” his career in film was over almost as soon as it had begun. Even the memory of Marceline’s film career was fleeting; like 70% of all the films from the silent era, Mishaps of Marceline has since been lost.

Keystone would likely have turned Marceline’s career around, or at least extended its twilight, but the apparent indifference with which Mishaps was met likely undermined Marceline’s already dwindling popularity. Likely of much greater importance to the august than any potential film career was his return to the New York Hippodrome. Like his dalliance in the world of narrative film, this, too, proved to be a disaster: “When Marceline came back to the Hippodrome in 1915 after a trip abroad, his crowds were already beginning to prefer the silent flutter of faces on a screen to the gayeties of a nimble droll.” In other words, Marceline had been made obsolete by the very medium that was making his admirer, Charlie Chaplin, a star. The rigors of age and declining physical fitness may also have played a role. During his peak years at the Hippodrome he would turn “a succession of somersaults around the ring, alighting on his shoulders and back and continuing without touching his hands to the ground in an almost indefinite series of aerial revolutions.” In contrast, one reporter would later reflect that “the agility of his youth had grown a bit a bit fat and flabby.” Whatever the precise explanation for this downturn, Marceline’s act no longer “took” at the venue that had hosted his antics since 1905. Later in 1915, he temporarily retired from show business and opened his first restaurant. It, too, was a disaster.

After Marceline’s return to the United States, very little in his life could be considered a success. Though he had been well paid as a Hippodrome performer, his two attempts to enter the restaurant business drained him financially and by the end of the decade, Marceline was once again forced to perform in order to make a living. That return to show business may not have been as difficult for the aging august had his star not waned as fast as it had in the years following his last Hippodrome performance. By 1918, Marceline had returned to the circus but he found little interest in his measured, nuanced act and was employed not as a featured performer but as an ensemble clown. During that time, Charlie Chaplin, who still fostered fond memories of his childhood muse, went to see Marceline perform when the Ringling Brothers circus came to town; he was deeply disappointed when he saw how little Marceline was revered by his new employer. As Chaplin put it, “I expected that he would be featured, but I was shocked to find him just one of many clowns that ran around the enormous ring—a great artist lost in the vulgar extravagance of a three-ring circus.”

Shortly after this Marceline’s wife left him. By the end of the decade, Marceline’s fortunes had completely unraveled. Had he known of the high regard in which Chaplin held him, perhaps his spirits may have been cheered—to be called a “great artist” by the auteur was high praise indeed. However, considering his own failed attempt to enter the film industry and the ease with which his admirers surpassed him in terms of fame and popularity, perhaps his then-apparent melancholy would have remained. According to one reporter, “he was Marceline, the artist, who had once been used—and he had taken no pleasure in it—as a measuring stick for young Charles Chaplin.” For his part, Chaplin visited the august after he had witnessed his rather anonymous 1918 circus performance but “he reacted apathetically” to the visit. “Even under his clown make-up he looked sullen and seemed in a melancholy torpor.”

Nor did the 1920s offer Marceline any meaningful solace. Having lost all of his money, and having been made irrelevant by the rise of cinema, the august continued to scratch out a living however he could, performing at low key benefits and at business dinners, a far cry from his former nightly audience some five thousand strong. In 1925, Marceline ordered what may have been his final costumed image as a means of garnering more attention for his failing act, though it does not appear to have helped. Just two years after that picture was taken he would be found dead in the rundown hotel in which he spent his last days—he had shot himself, surrounded by old pictures of himself in costume.

The suicide of one of New York’s most successful stage clowns proved to be a minor media sensation, conjuring, as it did, the image of an almost perfect tragedy. Writing two months after the incident, one newspaper correspondent would lament that, “The clown in every age has presented, despite his public buffoonery, a tragic sadness in private—from the fabled Pagliacci to the real life Marceline, who was found a month or so ago in a drab side street hotel with a bullet in his head, a suicide.” Another writer, again reflecting upon Marceline’s tragic and impoverished end, asked his readership, “Why do clowns kill themselves?” but the question was rhetorical. The same journalists who posed such questions were the same individuals who revealed the hitherto hidden details of Marceline’s last decade, creating a media narrative which connected his dwindling career directly to his suicide. Time Magazine, seizing on the presence of glory-day photographs found around Marceline’s body, perhaps went furthest with their speculative flourishes: “Marceline himself had to smile a little at those merry mocking faces”. Whatever ultimately motivated Marceline to take his life, the media revelled in the narrative they created around the event.

A Clown Resurrected

Lacking a meaningful record of his performances, Marceline’s place in the pop culture canon is tenuous. Having made his most important artistic contributions on the live stage, little remains for modern commentators to analyze, though in the February 27th issue of Reel Life (1915), an early motion picture magazine, there is just about enough fragmentary evidence to piece together a very basic outline of his only venture into narrative film making. By excavating the remaining visual record of Mishaps of Marceline alongside the only surviving outline of the film’s plot, something of Marceline can be recovered:

MARCELINE is a professional window washer. He goes from store to store with his mop and pail. First he gets a job cleaning a jeweler’s [sic] plate glass front, where he works havoc among the priceless valuable on display. Next he applies at a grocery, where he deluges the goods with soapy water.

This reconstructed storyboard of Mishaps provides some slight insight into the approach Marceline took to his comedy, the most notable aspect being the august’s use of his own face to convey emotion and sentiment, a deeply important part of his Hippodrome routine:

So expressive did he make his muscles that they literally talked for him in the vast spaces of the London Hippodrome, and little children could ‘get the joke’ when they might have missed it had it been finer…Thompson and Dundy [the Hippodrome’s owners] wanted a knockout bill for the New York Hippodrome, they went to London and imported the little Spaniard with his expressive muscles.

In the first image, Marceline’s slack features stand in contrast with the opposing actor’s more serious visage. In the scenes that follow, Marceline continues to present himself as relaxed and unknowing in the face of accusation, pathetic even in the face of some casual police brutality. Taking those scenes as a whole, it seems that Marceline’s window cleaner sailed through the opening part of the film, oblivious to his own destructive, antisocial ways, an idiot, but an innocently naive one. Contrast that with the penultimate image in the sequence in which Marceline stands defiant and dignified in the face of his accuser, and the final image in which he once again presents an expression of passive idiocy in the face of his opposition’s anger. Note also the noticeably disheveled hair of judge which seems to imply some lost joke or piece of physical comedy having occurred between the stills. In the absence of that lost piece, this reconstructed storyboard provides a glimpse into what it was that fueled Marceline’s popularity. They communicate something of the “loveable pathos” for which he was renowned, providing evidence of the “master of pantomime” at work. As Marceline put it in 1912, “While on stage I have a sort of feeling that I am playing a part and make people and make people see me as a character—a link in the story, as it were. I believe that sense of character must always lie behind ‘horse-play’ if it is to be really funny.” Marceline, it seems, was a master of situational comedy, inserting himself into events which did not involve him, and always to the detriment of those he was trying to aid. Writing shortly after his death, reporter Marjorie Dorman wrote that

Without speaking a single word, he was a master of pantomime, and as an example of the useless, well meaning individual who gets in the way of everybody, Marceline was a veritable scream. Who of those who watched him in his vain endeavors to assist the stage hands in rolling up the rugs of the Hippodrome stage will ever forget the short, agile, comic little man?

The Mishaps of Marceline storyboard illustrates that approach to comedy. So, too, does a somewhat less direct source, “The Merry Marceline,” a short lived comic strip from 1906, which was apparently edited by its eponymous star. Ridiculous in a way that set it apart from Marceline’s stage act, it nevertheless captured his enthusiasm for turning a well-intentioned deed into a disastrous farce.

At least some part of that which made Marceline a popular and entertaining comedian appears to have made the transition from live stage to more enduring mediums, but it is possible, perhaps even likely, that much was lost in translation. Studying the storyboard of Mishaps raises an important question—why did the film fail, why was Marceline unable to successfully make the transition from stage performer to movie star? It is possible, though impossible to verify, that Mishaps was not well made. The complete film may have failed to capture the comedic essence which had turned Marceline into a star but, more likely, it was the august’s insistence that he continue to wear his stage makeup that set him apart from—and at odds with—the comedic fashions of the time. Though Marceline’s face paint was modest when compared with the Grimaldi-inspired “chalky face” of his peers, it nonetheless contrasted with contemporary cinematic trends.

In the January 23rd issue of Reel Life there appeared a short article in which the writer described Marceline’s interactions with Helen Badgley and Leland Behnam, the “Thanhouser kidlets,” who, while visiting the august as he was making his film, plied him “with questions about clown life.” Though seven-year-old Benham was inspired by Marceline and “strut[ted] around wearing clown makeup,” Badgley made an astute observation, telling her partner that “he didn’t have to wear make-up…to be a clown.” This point seems to have been lost on Marceline. The clowns of the silver screen wore no makeup. That Marceline was able to inspire Benham speaks of his power as a live entertainer, but Badgley’s dismissal of the makeup was a much more important reflection of the cinematic era. Comedic tastes were changing and, by lingering in his own past glories, Marceline was unwittingly presenting himself as a relic. Whatever the quality of Mishaps, it was anachronistic and, in the face of Keystone’s growing output and increasing quality, a poor contender for success.

The storyboard above, showing as it does, Marceline’s use of his face to express himself, is a reflection of that which made him great. It was also a reflection of why his career stalled and imploded. Tastes changed, but Marceline did not.

In spite of his popularity in the 1900s and 1910s, Marceline and the artistry of his turn-of-the-century comedy remains lost to historians and critics alike. Unlike many of his clowning peers, Marceline’s humor was rooted not in ridiculous clothing, oversized shoes, bawdy verbalised jokes, or layers of white makeup. Instead his comedic roots were planted in mime and in the sharing of emotion between performer and audience, hallmarks of the era of cinematic comedy that would ultimately usurp him. Through careful readings of the happy memories he inspired among audience members, the reconstructed storyboard for Mishaps of Marceline, and the comic strip he inspired, we can see what it was that set him apart from his peers: what allowed him to play for ten straight seasons at New York’s largest venue, and what ensured that the luminaries of the next comedic generation, Chaplin and Keaton, would remember him as fondly as they did. Marceline and his films may be lost, but his artistry is not. We can do his memory justice by understanding his place at the peak of America’s comedic ladder at the turn of the twentieth century.