Blurred Forms: An Unsteady History of Drunkenness

During an evening of carousing and drinking at a Salisbury tavern, a soldier and his comrades were drinking to one another’s health. Then the soldier did the unthinkable: he drank to the health of the Devil. Boldly daring the Devil to appear, the soldier claimed that if the Devil did not, it was proof that neither the Devil, nor God, existed. The soldier’s drinking companions quickly fled the room out of fear, but they returned “after hearing a hideous noise, and smelling a stinking savour.” After returning to the room, the soldier had vanished, and all they found was a broken window, the iron bar within it bowed and covered in blood. The soldier was never heard from again.

This peculiar tale, told in 1682 by the Anglican minister Samuel Clarke, made up a part of his warning to all regarding the treacherous fates that awaited drunkards. The soldier made the fatal error of losing his wits and drinking to the health of the Devil, inviting the evil being into his world. This story, however, was only one of the terrifying possibilities outlined by Clarke. Illness, madness, bodily and spiritual destruction, and–ultimately–death comprised the tragic fates that awaited every drunkard.

Such critiques and warnings initially did little to sway daily drinking practices, but over time, the cries of those who stood in opposition to alcohol steadily grew louder. Murmurs in the mid-seventeenth century–shocked at the sudden increase of cheaply available spirituous liquors–increased to a roar of condemnation throughout the decades of the following century. By the turn of the nineteenth century, the damnations against alcohol had become a deafening clamor that came in the form of speeches, books, medical inquiries, and artwork. One aspect often featured in such anti-liquor declarations were the drunkards themselves–more specifically, the drunkard’s unsteady, untrustworthy body.

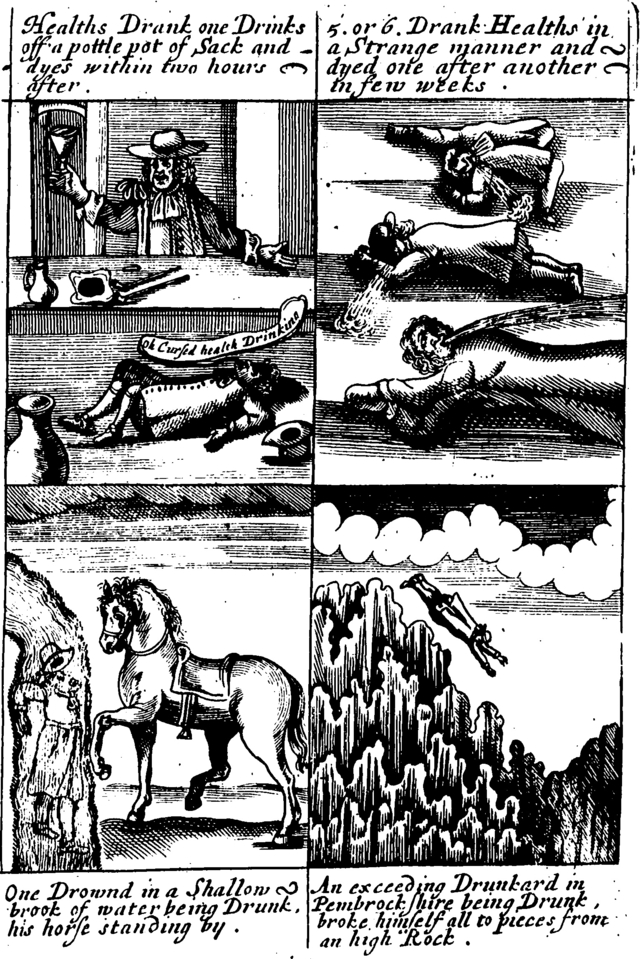

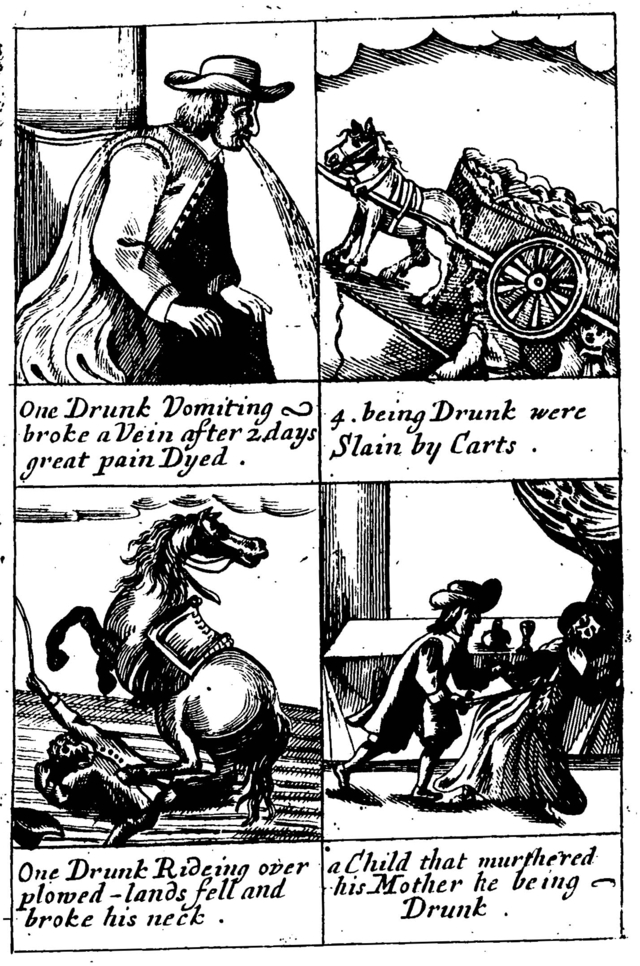

Samuel Clarke warned of a number of violent fates for drunks (eight of them pictured here) in his 1682 book A Warning-piece to All Drunkards and Health-Drinkers. Early English Books Online

Spiritual and medical inquiries about the effect of alcohol on a person’s body remained a constant source of concern, long before nineteenth-century movements for temperance. Published inquiries often emphasized the personal manner in which alcohol, after entering the body, initiated a process of deterioration and a literal process of physical transformation.

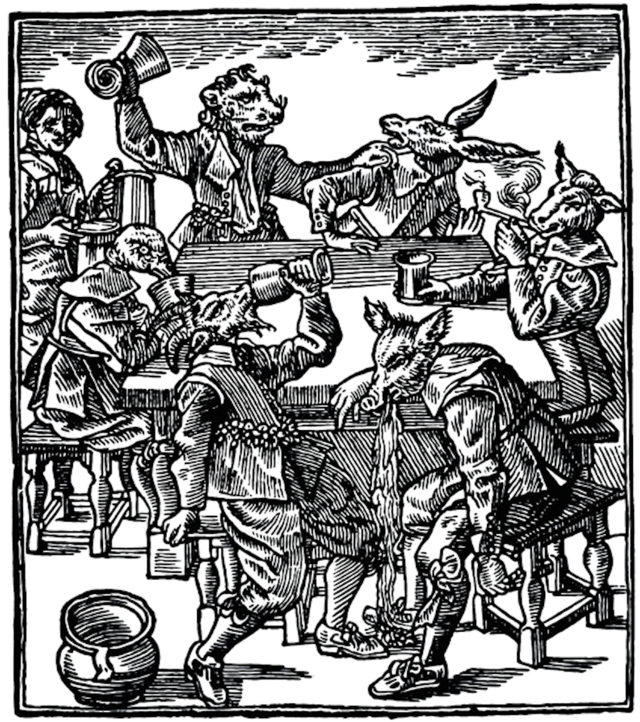

In 1677, Edward Bury, a former minister of Great Bolas in Shropshire, and a contemporary of Clarke, wrote at length about the ways alcohol distorted the body. He posed to the reader, “Consider also how much this Beastly sin of Drunkenness doth debauch, defile, deform the Body of man.” Drinking, Bury claimed, transformed the body–a perfect work of creation–by turning “the Nose, the Eyes, the Cheeks… red and pimpled, the Face swoln like a Bladder, the Countenance disturbed, writhen, and deformed.” To Bury, the most comparable creature to the drunkard was the swine, as drunkards seemed to take great pleasure in wallowing in their own vomit, dung, and the dirt. Drunkards even came to resemble swine by crawling about, after losing control over their ability to walk; though, while beasts are serviceable in this manner, Bury remarked, “the Drunkard [is] good for nothing but to spend and consume.”

Frontispiece of Thomas Heywood, Philocothomista, or the Drunkard, Opened, Dissected and Atomized (London: 1635). Senseshaper.org

To Clarke, imbibing alcohol did not turn men into swine, as Bury claimed. Instead, he claimed that drinking resulted in a much more profound transformation:

The bewitching, besotting nature of Drunkenness: It doth not turn men into Beasts, as some think, for a Beast scorns it… But it turns them into Fools and Sots, dehominates them, turns them out of their own Essences for the time, and so disfigures them, that God saith, Non est hæe Imago mea, This is not my Image…

Drinking altered the physical appearance of the body in a way that no other vice seemed to do. According to Clarke, by soaking one’s body with liquors, the drunkard experienced a process of metamorphosis; the body grew malleable, so much so that it was like soft clay with which “Satan can mould [the drunkard] into any shape.” Consuming alcohol could warp the drunkard’s features to the extent that his own Creator would no longer recognize his distorted face.

Spiritual concerns dominated early denouncements of drinking, but new observations of alcohol’s transformative power emerged in the eighteenth century. If a drinker, saturated in pernicious liquors, opened their bodies to Satan’s devious touch, man did not turn into beast. Instead, the body seemed to wither and collapse on itself. With a pallid countenance and leathery skin, the drunkard’s decaying appearance became one popularly associated with death.

The sudden rise in the drinking of gin amongst the poor of London at the turn of the eighteenth century brought forth a number of such claims. The bodily destruction was described as a gradual process; the drunkard’s constitution slowly broke down, their eyes–“except when lighten’d by the Fire of the spirituous Draught”–remained heavy and dull. The drunkard’s face was pale, their demeanor listless. If the drunkard was a woman, “the Bloom of her Beauty is soon changed for red Pimples in her Face,” and her complexion turned dull and sallow. Once the woman lost her beauty, a victim to her drunkenness, all hopes for marriage vanished, leaving the woman with truly no hope for the future.

Thomas Wilson, the Bishop of Sodor and Man, who also spoke in opposition to the increased consumption of gin, pointed out the ways in which drinking seemed to emaciate the drunkard, essentially reducing the body to a skeleton.

Such a description harkened an image that was unmistakably associated with mankind’s inevitable mortality. Overconsumption did not turn drunkards into beasts, or unrecognizable in the eyes of God, as Bury and Clark suggested; instead, these besotted individuals came to resemble the appearance all held once in the grave. The drunkard’s deteriorated body became a symbol of death, an unquestionable threat to all. Wilson was not the only to comment on such stark appearances. An eighteenth-century poem by Charles Darby likewise captured the haunting imagery of a skeletal drunkard:

The Actors in this Scene were not of one

Age, Humour, Figure, or Condition.

See One with hollow Cheek, meagre, and lean,

By Sipping-Hectick, e’en consumed quite,

As he a Skeleton had been,

Enough to put Death’s self into a Fright

This imagery became a powerful tool for organized opponents to alcohol. Quite often, the notion of a drinker who wasted away unto the point of death became a mainstay of anti-alcohol literature. Physicians who wrote about drinking’s effects did not shy away from such warnings either. Benjamin Rush, the famous physician from Pennsylvania, told the story of a man who failed to find satisfaction in his drinking. Always seeking out stronger tipples, this man moved from a daily toddy, to grog, to raw Jamaican rum, mixed with a tablespoon of ground pepper, to (as Rush stated) “take off their coldness.” Rush succinctly concluded this tale, without much expression of sympathy, or even surprise, when he stated that the man died, “a martyr to his intemperance.”

While Rush’s efforts against the consumption of alcohol certainly stood at the forefront of the emerging temperance movement, he, as well as other physicians, did attempt to convey some understanding of how drinking affected the human body. Rush noted the frequency of upset stomachs and vomiting the morning after a person engaged in heavy drinking. He also commented on the development of tremors in a drunkard’s hands, which could only be eased with a dose of cordial liquor, as well as a paleness in the face, contrasted against small, red streaks that appeared across the drunkard’s cheeks.

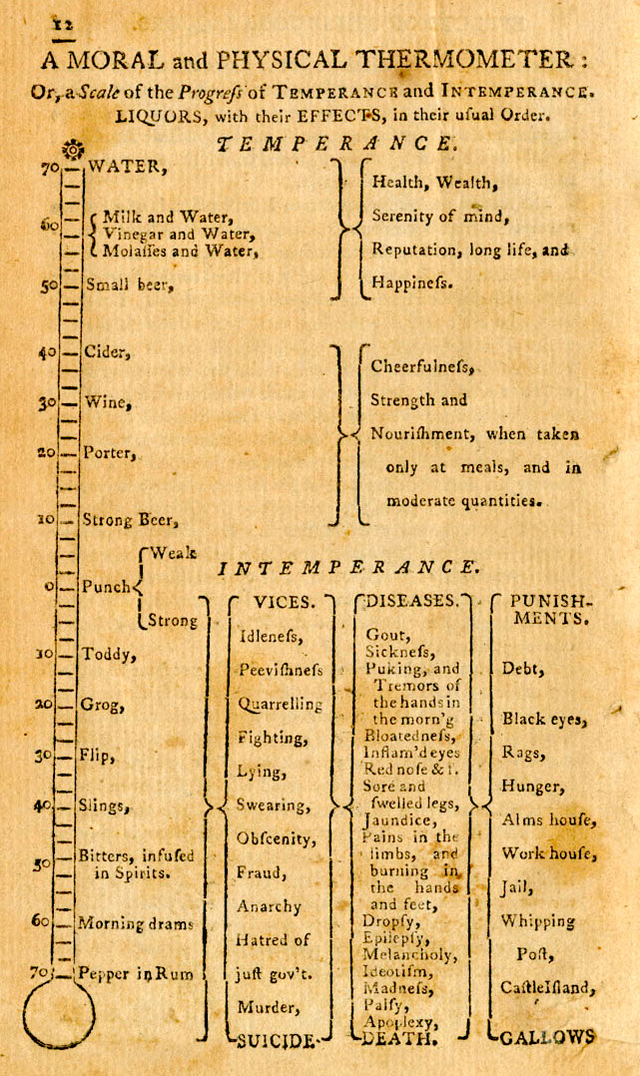

Rush’s “Moral Thermometer” of the effects of different forms of drink, ending with the deadliest, “Pepper in Rum.” Wikimedia Commons

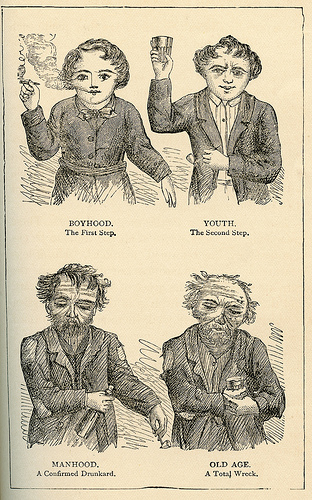

In A Treatise, on the True Effects of Drinking Spirituous Liquors, Wine and Beer, on Body and Mind, published in 1794, the anonymous author discussed the physical alterations caused by drinking. Initially, the author claims that drinking brought on an early form of aging–preventing “the growth of youth,” and mutating the young body so that it prematurely reflected the decay of old age. Throughout the piece, however, the author makes a claim–one that echoed the arguments made by Edward Bury a century before: that drinking not only aged the drunkard’s body, but by corrupting judgment, it made the drinker more beast than man.

By the final decades of the eighteenth century, questions began to arise regarding the proper amount of alcohol one should drink, or if one should drink at all. Due to the traditional association of alcohol and medicine, many physicians, ministers, and other societal leaders did claim that alcohol was perfectly acceptable to drink in moderation. Rush himself made this claim, but he carefully noted that only certain alcoholic beverages were acceptable to drink in moderation. Many of the more popular spirits, he stated, were not acceptable to drink at all, and those who did risked an array of diseases and punishments (with almost all ending in certain death).

Even as certain kinds of alcohol fell under scrutiny, however, the long-held notion that drinking in moderation remained acceptable likewise came into question. The previously mentioned anonymous author was especially critical of what drinking in moderation actually meant, stating:

[F]or instance, many a one would think three glasses of gin daily taken, to be a very moderate quantity, and another by drinking them would in a short time be thrown into a violent fever; for this reason it is impossible to determine the quantity that is harmless and that which will hurt.

Certainly, three glasses of gin a day might fall under suspicion as to whether that qualifies as “drinking in moderation,” but this question did mark a shift in the view that introducing alcohol–of any amount–into the human body could potentially lead to decay and transform a moderate drinker into a deplorable drunkard.

By the nineteenth century, organized advocates for temperance gathered to end the habitual consumption of the “demon drink.” Temperance literature often emphasized the inevitable “road to ruin” awaiting each person who made the unfortunate decision to drink. Timothy Shay Arthur, in particular, helped convince the American public of the dangers of alcohol through his popular novel Ten Nights in a Bar-Room and What I Saw There, originally published in 1854. Set in a tavern called the “Sickle and Sheaf,” Arthur lays out the menace of alcohol in dramatic detail. Throughout the novel, descriptions of drunkards, again, emphasized the physical deterioration drinking caused, revealing the continued importance of the body in anti-alcohol literature. In particular, the town drunkard, Joe Morgan, stands out in Arthur’s narrative as an unwanted but familiar element of the tavern. Arthur noted the physical decay habitual drinking had on the man’s body:

A glance showed him to be one of a class seen in all bar-rooms; a poor, broken-down inebriate, with the inward power of resistance gone – conscious of having no man’s respect, and giving respect to none.

Again, after the passage of a year, and with the return of Arthur’s protagonist to the same bar, comments on Joe Morgan appear once more:

He was standing at the bar, with an emptied glass in his hand. A year had made no improvement in his appearance. On the contrary, his clothes were more worn and tattered; his countenance more sadly marred.

Depictions of a demoralized local drunkard were only one aspect of the physical decline drinking wrought. In another, non-fictional book published by Arthur, Grappling With the Monster, he lays out the ways alcohol “Curses the Body,” stating:

One would suppose, from the marred and scarred, and sometimes awfully disfigured forms and faces of men who have indulged in intoxicating drinks, which are to be seen everywhere and among all classes of society, that there would be no need of other testimony to show that alcohol is an enemy to the body. And yet, strange to say, men of good sense, clear judgment and quick perception in all moral questions and in the general affairs of life, are often so blind… as to affirm that this substance, alcohol… is not only harmless, when taken in moderation – each being his own judge as to what ‘moderation’ means – but actually useful and nutritious!

Scarred, disfigured features mark the faces of drunkards–how evident it is that alcohol is an invasive “enemy to the body.” Also, once more, the issue of moderation is brought into question; is such moderation even possible? As the temperance movement gained full strength during the era of Arthur’s publications, it was no longer an issue of debate. Alcohol cursed the body, deteriorated physical features, and reduced the drunkard into a “broken-down inebriate”-far from our contemporary notion of a functioning alcoholic.

And yet, those dramatic warnings created a counter response–a skeptical backlash that questioned the validity of such claims. Did drinking really result in bodily decay? Could a person imbibe alcohol without turning into a beastly, mindless drunkard or an unwanted societal burden? Was it possible that the drunkard did not transform but vacillating observations did? A cartoon from Puck magazine presented a different image of temperance, one that struck a balance “Between Two Evils.”

To the right, an Intemperate Teetotaler appears, snobbishly refusing to even gaze upon a repulsive glass of alcohol. To the left, an Intemperate Drunkard, who, in many ways, reflects the same physical deterioration as described by temperance writers like Arthur. In the middle, though, sits a man who represents True Temperance. He holds a mug of beer, but no bodily decay marks the Temperate Man’s features; he is well dressed and of amiable countenance. While anti-liquor advocates long promoted the physical decline incurred by drinking, this figure represents quite the opposite. T. S. Arthur scoffed at the idea that alcohol could provide any source of nutrition. Benjamin Rush claimed that drinking at all would create an insatiable appetite for stronger drinks, leading, inevitably, to incurable drunkenness and death. Samuel Clarke warned that alcohol would open the drinker to possible corruption from the Devil.

Sitting between these two extremes, the Temperate Man grasps his mug of beer and, with a small smile, resolutely states, “I want nothing to do with either of you!”