Shameless, Villainous, and Wicked: a Keller Family History

The Story

This is my dad’s version of the West Point Hazing Scandal of 1900.

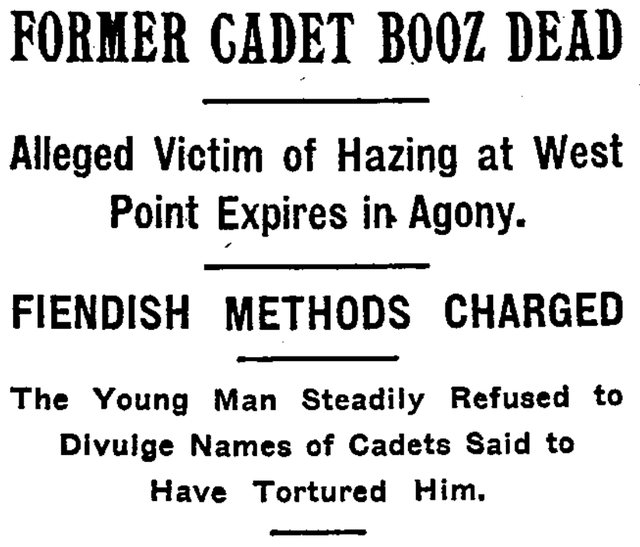

One hundred years ago, in an underground boxing match at West Point, my great-grandfather Frank Keller beat up a schoolmate named Oscar Booz so badly that Booz dropped out, moved home, and died.

The death looked like hazing: Keller was a senior, Booz was a freshman, and West Point had a well-known history of allowing upperclassmen to discipline new students. The media caught wind of it, the US Congress convened an investigatory committee, and then my great-grandfather, suddenly embroiled in a national scandal, had no choice but to travel to the capital to clear his name.

A trumpet screams and a headline spins into focus: Frank Keller, West Point cadet, interrogated by US congressional committee! My dad is always quick to assure me and my sisters that Keller was eventually cleared of all guilt. But the point, he says, is that it was by the fists of our great-grandfather that the people of the United States uncovered a systematic network of violence in their nation’s most prestigious military academy.

In conclusion, what a guy.

Like all family histories, this one has some holes. Chief among them is the resolution: if my great-grandfather really did beat up a classmate so badly that he died, shouldn’t he have been found guilty of something?

For an answer I looked to the online digital archives of the New York Times. The paper had extensive coverage of the scandal. From these records I learned that, in the courtroom and in the press, the man who ended up being put on trial wasn’t my great-grandfather, who had been cruel enough to punch a young schoolmate in the face and gut until he blacked out.

It was his opponent, freshman Oscar Booz—who had been too cowardly to fight back.

The Military Inquiry

On December 19, 1900, cadet Rigby Valiant described how he had been hazed at West Point:

[Valiant] had taken part in pillow fights and a “rat funeral.” The latter was held in his tent. The body of a dead rat was placed on top of a box and a towel laid over it. Four lighted candles were placed on the corners of the box. A high priest was appointed… Flowers were placed around the body of the rat. The services lasted about half an hour. Several upper-class men took photographs of the proceedings, after which the rodent was buried.

Who listened to this curious testimony? Not a congressional committee, it turns out, but rather a panel of judges on a military court of inquiry. The hazing scandal my dad described actually consisted of two investigations: the first by the US Department of War, the second by the US Congress. This double-investigation struck some people as unnecessary. John A.T. Hull, Chairman of the Committee of Military Affairs, said that military inquiry would already be exhaustive and critical and that “it was erroneous to believe that the army was interested in shielding West Point.” Unsurprisingly, nobody fell for that.

And with good reason, too, as the military inquiry into the death of a young man quickly devolved in a series of breezy chats with good boys about their madcap misadventures at boarding school. Cadets confessed to the court that they were forced to stand on their heads in bathtubs, crow like roosters, and eat pineapples soaked in quinine. Cadet Orfield Tyler said that sometimes the older students would sneak into the rooms of freshmen late at night, remove their socks, and proceed to drip candle wax on their bare feet. Cadet M. Shinkle of Ohio introduced everyone to the ‘Sammy Race,’ a ritual that was later described in an edition of the monthly magazine Judge’s Library:

Spoons were placed in the right hands of the victims. Both began to ladle out molasses and pretend to feed each other. It was nothing but pretense, for Willetts, by a good guess, daubed the whole of his spoonful over Griscomb’s shirt-front. Griscomb retaliated by smearing Willett’s trousers… It is the idea of the ‘Sammy Race’ to have the cadets unintentionally plaster each other with molasses.

An atmosphere of almost absurd merriment settled over the proceedings. Cadet Benjamin F. Miller, who had known Booz even before attending West Point and might have been expected to feel some remorse about his death, took the stand and talked about hazing “with his face wreathed in smiles.” Cadet Charles McEby told a funny joke:

[Examiner] Did you ever see a man faint while undergoing any of these exercises?

[Witness] Well, I have known a man to feign.

[Examiner] Under what form of exercise?

[Witness] Eagling, I think, Sir.

[Examiner] How long did he exercise?

[Witness] I can’t exactly say, about five or six minutes, I think.

[Examiner] Who was that man?

[Witness] Myself, Sir.

This reply caused laughter, in which the women spectators joined.

Laughing women spectators—a moment of sexual frisson! For at least some members of the audience, the inquiry of hundreds of West Point cadets served as a free, weeklong beefcake parade. When Cadet James M. Hobson testified, the reporter from the New York Times observed that “the women in the gallery stared at him and never took their eyes off the witness until he left the room.” Later on the same day, Cadet Hiram M. Cooper described how he had been forced to take a cold shower in summer. This “caused the women in the gallery to titter audibly.”

Booz and Keller didn’t fade entirely to the background. While on the stand, many witnesses made sure to remind the court that, objectively, Booz was big sissy—an opinion which met with a general consensus. On the second day of the inquiry fourteen cadets took the stand, and “all of them who knew Booz declared that his standing with his classmates was not very high, as they looked upon him as a coward.” Cadet McEby, the cadet who had pretended to faint when he was supposed to exercise, said that Booz remained a wuss until the very end: he “had not shown courage in his fight with Keller.”

In fact, over the course of the inquiry Booz was methodically stripped of any redeeming qualities. He was dumb: he was in the lowest section of math classes and about to fail out; according to his foreign language teacher, he “looked like a man who the more he had to learn the less he seemed to know.” He was dishonest: Cadet James Prentice claimed to have caught him hiding a book inside a Bible. He was feeble: according to Cadet Wade Carpenter, Booz’s eyes were weak and his legs were small and, if you thought about it, he “was not a strong man.” As ever with Booz, the cadets at West Point pulled no punches.

But perhaps the worst thing about Booz, and the reason he had been forced to fight Keller, was that he was proud. He retaliated against the upperclassmen who antagonized him. His big misstep came one night when he was on guard duty. Booz had been instructed to remain silent by West Point staff but was being prodded by an older cadet to speak; Booz eventually broke down and told the older cadet to go to hell. The upperclassmen understood this sullenness as arrogance and immediately arranged the boxing match to teach Booz a lesson. They drafted Keller to be his opponent.

To a reasonable person, the idea of beating up a guy for being a brat may seem extreme, but it became clear over the course of the inquiry that the cadets were unanimously unreasonable in one important way: they were obsessed with the idea of “conceit.” The social divides that marked American society were supposed to dissolve at the gates of West Point. As one graduate told the press, “the sons of a washerwoman and of a millionaire are on the same footing when they enter the academy.” The cadets who testified at the inquiry reiterated this point but, importantly, they offered it less as a statement of fact and more as a statement of purpose. They knew West Point wouldn’t become a beacon of equality by accident. It was their duty to make it one.

The methodology the cadets designed to achieve this goal was simple. First, select a freshman with an overlarge ego. Second, force him to undertake an embarrassing or slightly uncomfortable task. Third, prove to him that he is no better than his peers, and then fourth, welcome him back into the fold of warm, loving brotherhood. This process served its purpose for many students. For them, hazing was simply a small painful step on the road to popularity. Cadet Fred Deen, for example, admitted that as a freshman he had been badly bruised in a fifty-eight round boxing match with an upperclassman, but that it wasn’t that bad because “he came out of the fight with glory.” Another cadet pointed out that popular cadets were subjected to more harassment than their unpopular peers, and that being ignored was much worse than being abused.

But the cadets’ discipline system broke down for Booz. The abuses he suffered did not gain him entrance into a heady ring of fraternal bonhomie. Rather, according to the testimony given during the military inquiry, all he achieved in his match with Keller was an affirmation of his across-the-board awfulness. Even immediately after the fight, two cadets continued to provoke Booz. Cadet Orfield Tyler told him that he had not “acted exactly fair” during the match, and Cadet John Herr chided him “that his actions were cowardly and were so regarded by the others.” To give a sense of how universally disliked Booz was, Tyler and Herr were the cadets Booz had selected to be his seconds in the boxing match, two schoolmates he evidently felt close to at the academy (a feeling that Cadet Tyler was sure to confirm was in no way mutual, assuring the court that he only served as Booz’s second because Booz had asked and he “could not well refuse”).

Booz was left alone after his loss to Keller. He withdrew from school a few months later. At the close of the military inquiry into his death, the judges found no reason to censure anybody at West Point.

The Congressional Committee

The congressional investigation convened about two weeks after the conclusion of the military inquiry. The atmosphere was markedly more confrontational. The charge against West Point was led by congressman Edmund H. Driggs from Brooklyn, a second-term Democrat who would sometimes decline to question a witness and instead shout broadsides at him:

[Driggs] You are satisfied that you hazed Mr. Macarthur?

[Cadet Dockery] Yes, Sir.

[Driggs] Did you think it was cruel?

[Cadet Dockery] Yes, Sir.

[Driggs] Well, young man, for your information I will tell you that I think it was atrocious, base, detestable, disgraceful, dishonorable, disreputable, heinous, ignominious, ill-famed, nefarious, odious, outrageous, scandalous, shameful, shameless, villainous, and wicked.

In the words of a New York Times journalist, who I suspect had been sitting on this one for weeks, Driggs handled all the witnesses he faced “without gloves on.” He sneered that one cadet was having a “convenient memory” when he forgot the details of how he had hazed underclassmen. He detained another cadet on the stand for hours until the witness almost broke into tears. One day, he badgered a cadet so brutally that the congressional chamber had to be cleared because all of the spectators were hissing.

The congressional committee quickly discovered that hazing at West Point was not the lark it appeared to be during the military inquiry. Cadets reluctantly confessed to physical exhaustion, hysterical convulsions, hospital visits, and nights passed in dark tents listening to their whimpering classmates. One cadet described a boxing match he had participated in during his first month at the academy:

Shannon hit me a couple of times on the jaw and I was knocked down. I don’t remember anything more until I came to lying on the ground. My seconds told me the fight was over and Shannon had won. Then I dressed myself and returned to camp. My jaw was sore and swollen. I could not eat anything at breakfast, and I went to the hospital. The surgeon there examined me and said my jaw was broken. I was in hospital for two weeks.

The investigation revealed a system of hazing that was not only brutal, but complex and institutionalized. Upon entering West Point, freshmen were assigned upperclassmen to whom they would act as manservants. A young cadet was expected to sweep his superior’s tent, make his bed, do his laundry, prepare his clothes, and discharge any other duties as necessary. Breaches in conduct were referred to an elite standing committee of upperclassmen. If the crime was deemed severe enough, this “Fighting Committee” would assign an upperclassman to face the freshman in a secret boxing match. If he wanted, the freshman could nominate another classmate to replace him or simply refuse to participate. But the costs were high: any student who didn’t fight “would be cut and ostracized by the whole corps.”

The cadets doubled down on the defenses they had put forward during the military inquiry: hazing eliminated weakness and purged arrogance. They said it was for the benefit of new students, teaching them “the necessity of prompt and unquestioned obedience.” They held that it wasn’t that severe; one cadet pointed out that regular assignments at West Point were much more taxing, recalling a summer night when, during a parade, thirteen men had fainted from exhaustion. And, of course, they repeated the line that had worked so well with the military judges: any man who was afraid of a little horseplay was a coward and had no business in the army.

The members of the congressional committee did not take this opportunity to remind the cadets that cowardice was not grounds for assault; far from it, they threw themselves into the fray and started identifying all the people they thought were cowards. Congressman Driggs, having established his macho man credentials through his encyclopedic knowledge of boxing, denounced the code for fighting at West Point as “infamous and unmanly.” The cowards, he said, were the upperclassmen who allowed the hazing to continue. So fervent was his belief that at one point he stood up, leaned against the bench, waved his finger at the witness, and bellowed that the culture he had revealed at West Point was nothing more than “brutal bullyism.”

Ironically, perhaps because Congressman Drigg’s examinations revealed several instances of abuse much worse than had been inflicted on Booz, the fight between Keller and Booz (and the variety of other small abuses that Booz had suffered) received relatively little attention from the court. A few cadets noted that Keller was a pretty small guy and a bad fighter, hardly the sort who could kill a man in a single blow. One cadet who witnessed the fight between Keller and Booz believed that Booz was never knocked out—he just fell down and chose not to get up. In its final report, the congressional committee decided that Booz’s death could not be formally attributed to his mistreatment at West Point.

But the judges did offer a general indictment of the hazing practices they had uncovered, saying that “something at the academy has benumbed the consciences of most of these otherwise creditable young men as to the treatment due from the strong and experienced to the weak, the embarrassed, and the inexperienced.” They had zeroed in on the central contradiction of hazing at West Point: in an effort to create a society in which everyone was equal and nobody was conceited, the cadets had actually built a system of informal indentured servitude enforced by physical abuse. The result of hazing wasn’t the elimination of arrogance among underclassmen—it was just the enablement of cruelty among upperclassmen.

Some cadets were unimpressed with this interpretation. Unrepentant, too; in the words of cadet Charles Burnett, “I would like to say that Congress and the people do not understand West Point.”

The Fight

So what about my great-grandfather—did he kill Booz?

On the afternoon of August 6th, 1898, a group of West Point cadets gathered at Fort Putnam, a secluded spot on campus. Three sentinels were dispatched to watch for any approaching faculty members. Frank Keller and Oscar Booz entered a small boxing ring, the boundaries of which had been created by the bodies of their classmates. Both fighters had stripped to the waist.

Although Keller and Booz had been matched for size, Booz was still slightly taller, broader, and heavier. Keller had never been in a fight before. The result of the match was not preordained—Keller’s classmates told him he would have a “tough customer.”

When the timekeeper called for the first round to begin, Booz immediately launched a volley of punches. He landed several blows on Keller’s shoulders. Keller fended off this attack without serious harm, and after about thirty seconds he saw an opening: he landed a hit under Booz’s left eye. Booz started bleeding. When he saw the blood, he started crying.

Booz stopped fighting in the second round. He turned his back and tried to run away, but the barricade of human bodies surrounding the ring was unmovable. Keller yelled at Booz, threatening to punch him in the back if he continued to show cowardice. Booz didn’t respond. The spectators taunted Keller. They demanded that he put an end to the match.

So Keller punched Booz in the back. And then he did it again two or three times. Booz fell down and the referee picked him back up. Booz turned around to face Keller and got punched in the right eye. Again, the referee lifted him up and instructed him to continue. The final blow was delivered to Booz’s stomach. Keller believed that it “was neither a knock-down nor a knockout blow,” but Booz remained motionless on the floor until the round had finished and he had officially surrendered.

Afterwards, Keller crossed the ring and extended his hand to his opponent. Booz, one hundred miles away from home and bleeding on the ground, took it. According to my great grandfather, he was smiling.

Did he think it was over?