Angelica’s Baby: Pregnancy Narratives in Twentieth-Century Rio de Janeiro

On the morning of December 22, 1911, in the height of the Rio de Janeiro summer, Angelica de Lourdes felt sharp pains in her stomach. A sixteen-year-old migrant from Northeast Brazil, she worked as a nanny and lived in the home of her employer’s mother-in-law, in the current-day Maracanã neighborhood of Rio de Janeiro. Not feeling well, Angelica went into her room to lay down, and a doctor was brought in. After examining Angelica, he decided a midwife should be called as the girl was in labor. By the time the midwife arrived, however, Angelica had already delivered a dead newborn—it sat wrapped in blankets on top of the bed. The midwife noted bruising around the child’s neck and mouth. She believed the marks to be the signs of a violent death, and she voiced her suspicions to Angelica’s employer, Dr. João Baptista, who, it seems, then notified the police.

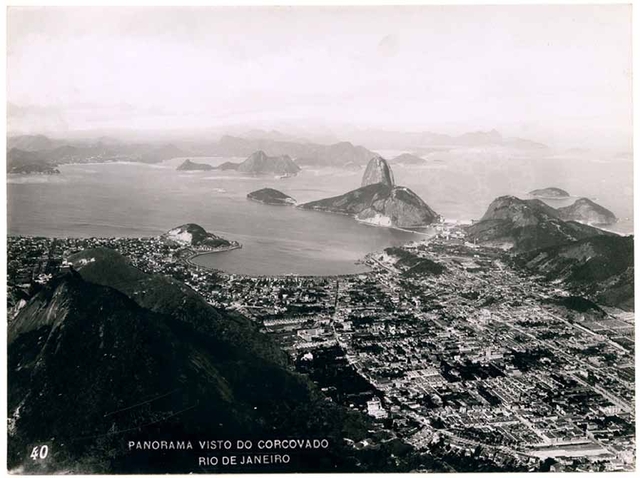

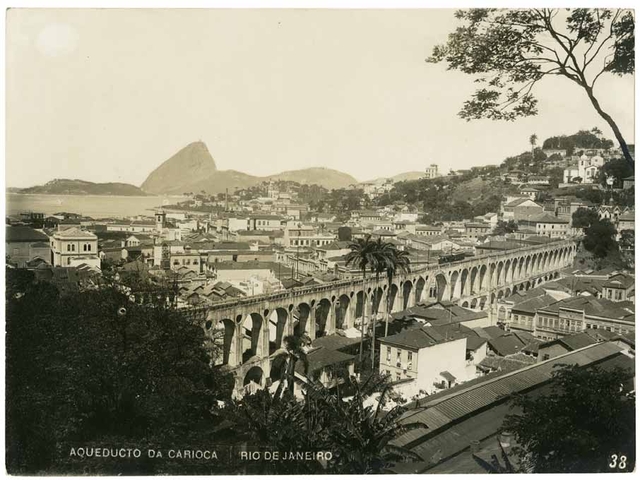

View of neighborhood next to the home where Angelica worked as a nanny, circa 1910. Aqueducto da Carioca, Rio de Janeiro. Photograph album collection, Department of Special Collections, Charles E. Young Research Library, UCLA

The police brought Angelica in to the neighboring precinct for questioning mere hours after her exhausting delivery and the subsequent loss of her child. In her statement, Angelica declared denial not only of her pregnancy but also of the cause of her labor pains—that is, until she delivered and saw the actual child. She told the police that she had been “violently raped” by her employer’s gardener exactly nine months earlier. The gardener, Antonio de Almeida, confirmed that he was the father of Angelica’s child. Yet, Antonio described the rape in less violent terms than Angelica. In his eyes, he had “deflowered” her and had planned to repair the damage to Angelica’s honor through marriage. Several months after the rape, Angelica “noted that her belly was growing little by little [but] because she did not know the signs of pregnancy, she was unaware that she was pregnant.” Angelica’s fellow domestic servants also cited ignorance of Angelica’s physical pregnant state. For example, one witness stated she “was unaware that the minor [Angelica] was pregnant, judging that the growth of her belly was fat.”

Angelica’s denial continued well into her labor. She testified that on the day she gave birth, after lying down because of the pain, “she observed a phenomenon to her unknown and that it consisted of a large volume of liquid falling from her sexual organs and after [that] she felt that organ dilating and out of it came a volume, that at the beginning, she did not know what it was but after she saw that it was a child.” Angelica’s account rings rather formal and distant if we consider the intense physical experience of labor and delivery. Her testimony was clearly mediated by her police questioners and translated into an “appropriate” tone that fit into the burgeoning technical investigative tradition of the Brazilian civil police. This official mediation erased Angelica’s physical and mental experience of labor and delivery. It dulled down the pain, fear, and surprise that probably consumed Angelica for the sake of bureaucratic expediency.

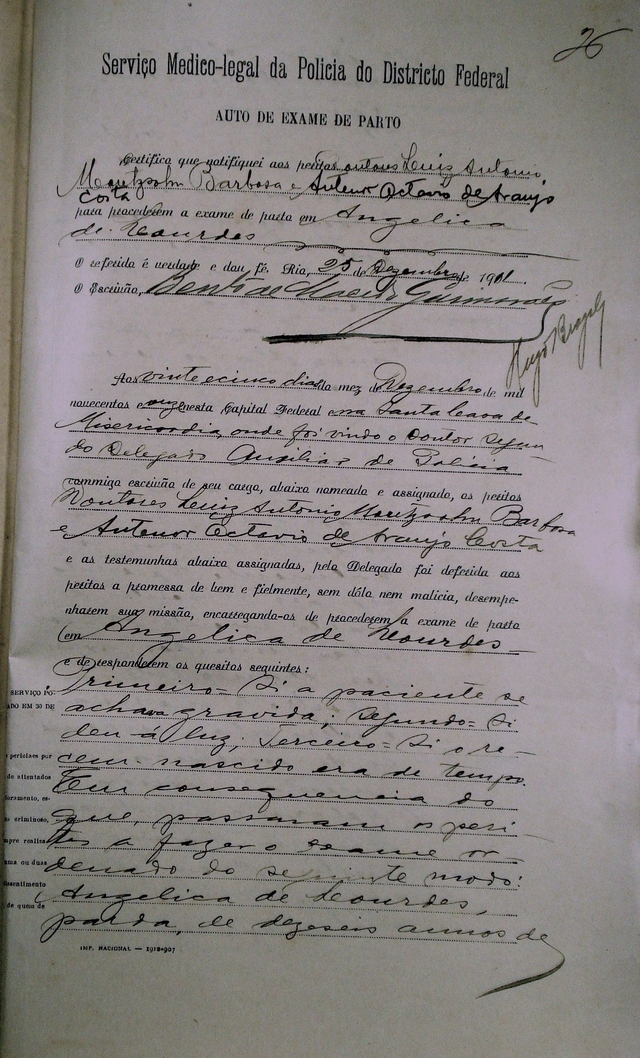

The first page of Angelica’s police testimony. Arquivo Nacional, Rio de Janeiro (AN) CR.0.IQP.466 (1911)

The subsequent police investigation tried to understand if Angelica was guilty of infanticide—the willful killing of her newborn infant after giving birth—or if the infant had died due to the conditions in which Angelica had delivered the child. Despite the medical attention Angelica allegedly received both before and after the delivery, she gave birth alone in her room. Angelica’s employer, it seems, did not send anyone to help her while the midwife was on her way. After noting that Angelica was unwell, the cook had asked the girl through the closed door if she was feeling okay, and after hearing the affirmative, “she [the cook] returned to cooking and taking care of her duties.” Domestic life continued as usual in the home where Angelica lived. Angelica’s delivery was perhaps no more pressing than that day’s supper.

The police’s forensic specialists’ autopsy of the infant declared that the newborn had been born alive and had died within thirty minutes, but not from manual strangulation as the midwife initially suspected. Instead, they cited the cause of death as a skull fracture and a consequent internal brain hemorrhage. Angelica told investigators that during the delivery and after she had seen the child’s head, she had “in the desperation of pain … guided her hands to the area to grasp the child, [and] forced its delivery and let it fall to the floor.” After passing out briefly, Angelica came to and “noted that the child was dead, not knowing if the death occurred in the moment in which she forced the exit of the child or if it was in consequence of the child’s fall after its birth.” Angelica presented her supposed denial of her pregnancy and the subsequent ignorance of “how to give birth” as the reason behind the newborn’s death.

How I Met Angelica: Police Investigations in the Archive

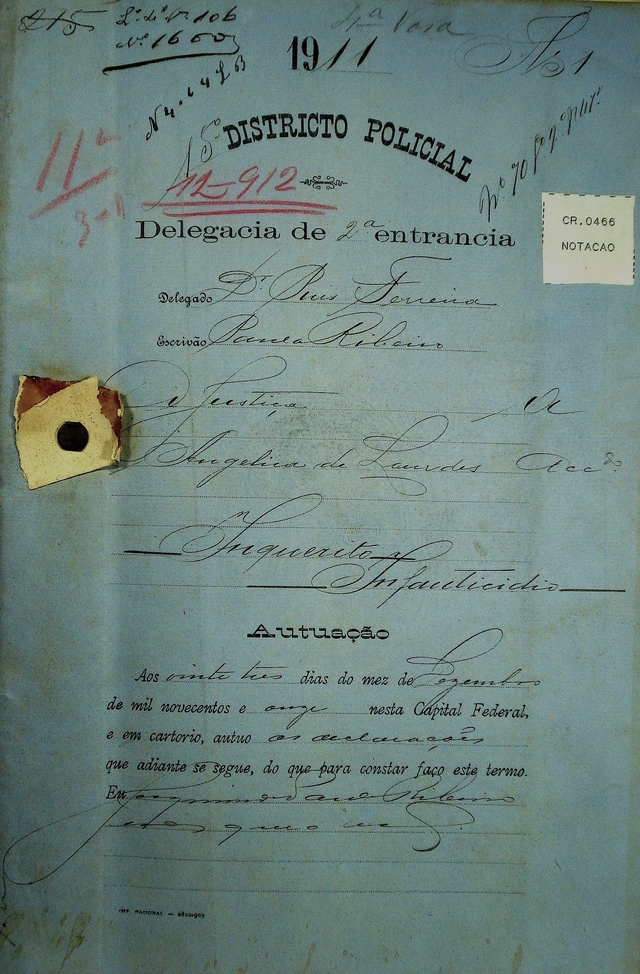

Cover page of Angelica’s police investigation. Arquivo Nacional, Rio de Janeiro (AN) CR.0.IQP.466 (1911)

I first met Angelica in the National Archive in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, while researching the lives of women investigated and prosecuted for abortion, infanticide, and child abandonment. I found Angelica’s testimony among numerous other cases involving women in similar situations. Reading through her police investigation caused me to ponder the interconnectedness of difficult home births and possible infanticide charges. Her (non) experience of pregnancy and labor unfold among the yellowed pages of police-guided testimony, forensic exams, and judicial decisions. Angelica’s police investigation consists of thirty-four double-sided handwritten sheets of faded paper with smudged ink. In its pages, the police question Angelica’s employer, the midwife who arrived after the birth, Angelica, the gardener who raped her, and two other women who worked in the same home.

Two forensic exams also appear in the case: an infanticide autopsy on the infant and a pelvic exam—called a “birth exam”—on Angelica that determined she had recently given birth. Angelica’s reproductive life is narrated and re-narrated throughout the case, appearing in the droll police script and the scientifically distant forensic exams. The latter is even more eerie when we remember that a pelvic exam implied that two police doctors touched and examined Angelica’s body almost immediately after the delivery—exacerbating an already terrifying experience. The two doctors squeezed her breasts to show that they were filled with milk. They checked the dilation of the cervix and prodded her stomach, citing that “pressure [on the area] was still painful [for the patient].”

Both the bureaucratic language of the witness testimony and the scientific prose of the forensic exams initially distanced me from Angelica’s experience. When I tried to think about the pelvic exam, I became physically uncomfortable. I struggled with how to read these sources, how to process my own reactions to Angelica’s experience, and how to find her in these texts. It was only after re-reading the case numerous times that I began to break through the police and medical language. I found Angelica’s voice by repeatedly plunging headfirst into her story.

Although heavily mediated by the police—all testimony and questioning were recorded by police clerks—these cases provide glimpses into women’s experiences with pregnancy at a time when little is written about the subject and even less is discussed about the lived experiences of the women involved. But there is a certain risk in reading criminal sources involving cases of pregnancy and supposed or attempted fertility control, here in the form of a possible infanticide. We must be careful not to only assume the criminality of the woman in question or chalk up her supposed ignorance as a tactic to avoid prosecution. To be sure, there were cases of infanticide and supposed ignorance that, in all likelihood, were calculated attempts by women in the face of the police. But feigning ignorance was not the only form of asserting one’s will. Every kind of historical source has its limitations, as these dry and technical police reports certainly do. We cannot limit our understanding of women’s lived experience of reproduction because of such restrictions. Unfortunately, historical information about the experience of pregnancy, childbirth, and newborn deaths that includes women’s voices, however mediated, are often only found in criminal documents. While other sources such as medical dissertations and journals may describe childbirth from the physician’s point of view, they include women as objects of study and not as protagonists in their own reproductive lives. Moving beyond reading Angelica’s experience as criminal allows us to explore her reproductive denial and its outcomes as one of the many possible and probable physical realities of pregnancy and childbirth.

Case Closed

The police took a sympathetic view towards Angelica’s plight, an opinion that might have stemmed from her supposed virginity at the time of her rape, her lower-class status—demonstrated by her illiteracy, migrant condition and occupation—or the other witness testimony that did not support the hypothesis of infanticide. The district police chief in charge of the investigation cited that Angelica’s denial of her pregnancy stemmed from ignorance and not criminal intent. He wrote in his summary remarks: “A young girl from the North, naïve and ignorant, unaware of her [pregnant] state, did not know what was causing the growth of her belly.” He re-narrated the events of Angelica’s pregnancy, without changing her story. He described that when she began to feel the initial pains of labor, she went to her room where her water broke, and “a large body came out of her sexual organs that she did not know what it was.” “Agitated,” she grabbed the infant by its head to help with delivery, causing its skull fracture and subsequent death. The verdict in the eyes of the district police chief: involuntary infanticide. The public prosecutor, representing the state, corrected the police chief’s view, stating that there was no such thing as involuntary infanticide, as the criminal intent to kill was the key component to the crime. In fact, the charge was involuntary manslaughter for which Angelica was also found not guilty. The public prosecutor closed the investigation without going to trial. Angelica’s social circumstances initiated the police investigation, but they also mediated its outcome. All levels of the law saw Angelica’s lack of knowledge as definitively linked to her poverty, and as the reason the death of her child was not a crime, reiterating Angelica’s own assertions.

Maternalism

Beginning in the nineteenth century, Western society assumed that women had an intuitive sense of their bodies, which, when dealing with the issue of pregnancy inherently tethered them to their latent maternal instincts. Thus, in turn-of-the-twentieth-century Brazil, the police employed poverty and its supposed counterpart, ignorance, to explain the paradox of pregnancy denial in a maternalist culture. But a similar disconnect between the practice of infanticide and women’s “inherent” maternal nature existed. In fact, early-twentieth-century Brazilian infanticide law assumed a level of psychotic disturbance in the women involved. In the 1890 Penal Code, in place until 1940 and under whose laws Angelica was investigated, the crime of infanticide was the direct or indirect killing of a child in the first seven days of life. However, if the mother of the child committed the crime to hide her own “dishonor,” the prison sentence was reduced from the original six to twenty-four years to a lesser sentence of three to nine years. While the infanticide law did not include a specific mention of psychoses, in practice, juries often acquitted women brought to trial for infanticide for acting in a state of post-partum madness.

This practical application of the law was encoded in the very definition of the crime in the revised 1940 Code. In effect to this day, the 1940 Code states that infanticide is a crime that only the child’s mother can commit: “Infanticide: To kill, under the influence of the puerperal state, one’s own child, during the birth or immediately after.” This change codified in law the idea that only a woman in a state of post-partum “madness” could effectively kill her child. In other words, a rational woman could not reject motherhood in such a violent manner. Moreover, the 1940 Code erased any reference to “honor.” While the 1890 Code had a reduced prison sentence for women “hiding their dishonor,” the 1940 Code rejected the idea that a woman would rationally kill her newborn to hide her dishonor. After 1940, only complete madness explained the event.

While infanticide and the denial or concealment of pregnancy are different events (although at times the former follows the latter), they both fly in the face of the logic of a maternalist society that reduced a woman’s nature to her biological ability to reproduce. Investigations of pregnancy denial at the turn of the twentieth century remedied the paradox of its existence by citing ignorance. Infanticide law similarly rectified the inherent contradiction between a woman’s nature and the act of infanticide through the idea of madness.

A Twenty-First Century Angelica?

Contemporary scholars have shown that the denial of pregnancy can precede infanticide. But denial or concealment of pregnancy did not and does not always imply infanticide, and in current-day literature, this connection only exists in a small percentage of denial cases. Nevertheless, neonaticide (killing a child immediately after birth) remains “strongly associated with pregnancy denial.” Currently, denial of pregnancy is classified into three categories: affective, pervasive and psychotic. Women in affective denial intellectually recognize their pregnancy but do not change their behaviors. Pervasive denial is “when not only the emotional significance but the very existence of the pregnancy is kept from awareness.” Empirical evidence suggests that physical symptoms associated with pregnancy are milder in women with pervasive denial. Women with pervasive denial can also feel dissociated during the actual delivery, much like Angelica. Psychotic denial includes women who deny pregnancy in a delusional manner. While the first two categories often include the concealment of pregnancy, psychotic denial normally does not. Angelica’s alleged lack of knowledge falls in line with current definitions of pervasive denial.

Cases of denial and concealment of pregnancy today are not uncommon occurrences. Anyone who has watched TLC’s reality show, “I Didn’t Know I Was Pregnant,” can attest to their existence. Empirical data has demonstrated that popular ideas about denied pregnancies as rare events are not true. Yet in the contemporary popular imagination, women who state they did not know they were pregnant are seen as lying, as the prevailing belief is that it is impossible to not know one is pregnant. Contemporary society expects that women, whether experiencing a first or sixth pregnancy, will know that they are pregnant. This knowledge is assumed to be an essential part of women’s identity and makeup. Legal battles in the U.S. today over the pregnant body play on maternalistic assumptions. A recent case in Texas demonstrates how the law can be interpreted to imply that even a brain-dead pregnant woman should be kept on life support in order to fulfill her maternal duty and deliver her child. The contested nature of the female body—in particular the visibly reproductive one—continues to be waged through its embodied experiences.

If we move backwards in time and across continents, we see that maternal claims also played a key role in legal interpretations of cases like Angelica’s. And while the medical “truth” of a woman’s inherent maternalistic instinct was reiterated in legal and political understandings of their “natural” roles as mothers, at the time of Angelica’s investigation there was some wiggle room in the Brazilian legal understanding of pregnancy experiences. Despite the rise of maternalist thought, Angelica’s case demonstrates that the practice of early-twentieth-century Brazilian law still allowed for the possibility of pregnancy denial. Even though the legal and medical exaltation of motherhood had gained full force in Brazil in the early-twentieth century, evolving into a belief in scientific motherhood influenced by the growing hygiene and eugenic movements, the law still carved out a space for women’s empirical pregnancy experiences.

I find myself wondering what happened to Angelica after the end of her police investigation. The archival documentation stops, but Angelica life continued on. Did she stay on as a nanny in the home of Dr. João Baptista? Did she marry her rapist Antonio de Almeida? Did she become pregnant again and have children? Angelica’s traumatic encounter with the police may be the only documentary evidence she left behind, but her story allows us a glimpse into the reproductive lives of many women in early twentieth-century Rio de Janeiro. It remains etched into my mind as an example of the importance of the physical body—of Angelica—in our understanding of history, the archive, and continued contestations over female reproduction.