Fever to Tell: Interactive Storytelling Online and the History of Philadelphia’s Yellow Fever Outbreak, 1793

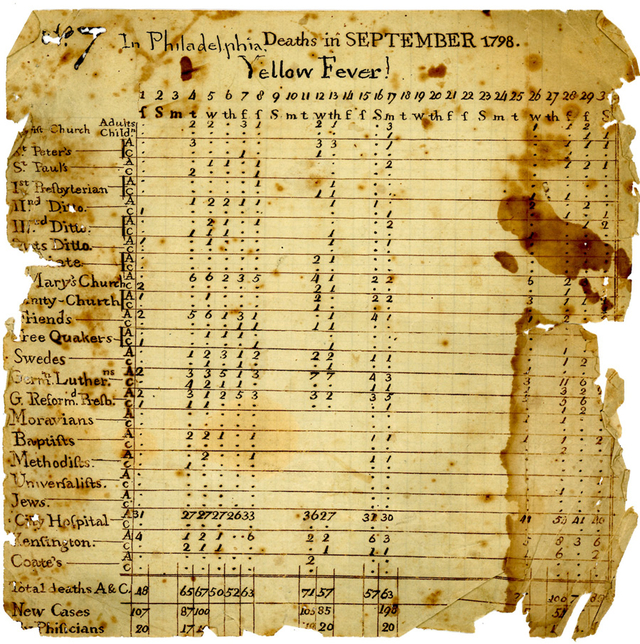

Yellow fever outbreaks in Philadelphia reoccurred throughout the 1790s (this document records deaths in September, 1798) but they hit the city hardest during the summer of ’93. Philadelphia Archdiocesan Historical Research Center

In July, 1793, Philadelphia was a city of 50,000. Four months later, its population had been cut in half. Upwards of 5,000—one tenth of its population—had died horribly of an unsuspected illness: vomiting blood, they had been infected by Yellow Fever. Another 20,000 had fled the city, among them President George Washington, as Philadelphia was then the nation’s temporary capital.

Some of us wax romantic about the past, ranking the top five historical events we wish we could ‘be there’ to see. Philadelphia’s terrifying Yellow Fever outbreak is likely on few people’s lists. Nevertheless, for the last year web developer and historian Rachel Ponce has been crafting a narratively compelling—and non-infectious—way to come close: an interactive story named “The Fever” that we’re excited to host online in this quarter’s edition of the The Appendix. In the piece (which you can read here), the reader takes the place of a fictional doctor, puzzling through an unknown disease that scythes through his patients and, if the wrong choices are made, his family as well. It is horrific, but also hugely entertaining. There are sixteen possible endings to seek, and various badges to collect along the way, giving it wonderful replay value. It might be likened to Choose Your Own Adventure novels, if Choose Your Own Adventure novels ended in a haze of black vomit, a back-alley stabbing by a pimp, or the irretrievable loss of a child.

Lest that sound too dark, we interviewed Ponce about her incredible achievement. It is a piece of entertainment, to be sure, but it also guides the reader to certain hard-won insights about the nature of medicine in the late eighteenth century; the fractures of race in Philadelphia that discriminated against the black nurses who stayed in the city; and the position of power a white male doctor inhabited—that a disease could nonetheless lay low. We hope you explore Ponce’s meditations on her process, and then enjoy the story itself. This is one of those pieces The Appendix is absolutely made for, and we’re thrilled to share it with you.

What interested you about Philadelphia’s Yellow Fever outbreak?

There are a great many things that interest me about Philadelphia’s Yellow Fever outbreak, but the reasons why I chose this particular incident for my story have mostly to do with trying to help readers understand what a confusing, trial-and-error filled landscape early American medicine was.

History of medicine is one of those topics that really tends to get glossed over in schools, and I think because of that we’re both paradoxically awestruck with and frightened by modern medicine. We love the TV dramas that make our modern doctors look like gods, but often our own personal encounters with modern medicine are often far from perfect, and our doctors far less than heroic. And of course that’s to be expected—life rarely plays out like a scripted drama! But I think a lot of disillusionment gets created when we experience the disconnect produced by our fundamental misunderstanding about how medicine works and how it has come to be the practice that it is.

So what really drew me to telling a story setting in the time of the Philadelphia Yellow Fever outbreak was that it rather naturally presented opportunities for exploring the human side of the history of medicine by exploring the themes of duty, compassion, uncertainty, and fear. I wanted readers to think about the history of medicine in the context of a situation in which human reason seemed to be breaking down in the face of the unrelenting force of nature. Because to me, exploring these moments really helps us to question and to understand the kinds of things we as a society must do to prevent those kinds of breakdowns in the future.

What suited it for this very particular format?

I think the great thing about setting this story in the midst of an epidemic is the fact that it places the reader into a story that is likely to be foreign to him or her in the particulars, but yet the situation isn’t so unfamiliar that it wouldn’t still resonate with a contemporary audience. It’s foreign in the sense that most people living in the U.S. today just don’t have any memory or experience with epidemic diseases. But even though we’ve conquered many of the particular diseases that were so frightening for so much of human history—like smallpox and yellow fever—the threat of epidemic disease certainly hasn’t gone away. So I definitely believe it’s worth thinking about just how far we have come and what a luxury it is not to live in fear of these particular diseases today, but also, to understand just what the experience of epidemic disease was like, because we’re not really out of the woods, so to speak.

Another reason I really like the setting of the yellow fever epidemic was the fact that it presented a lot of possibilities for horrible ends for the player/reader. Perhaps that sounds a little trite at first, but when you’re trying to construct a work that is more game than linear narrative it’s actually quite important to have a great many ways to reasonably conclude each of the various story lines. Player actions need to have consequences so that each choice doesn’t just seem important, but actually is important. And of course the most obvious consequence you can throw at a reader/player is their character’s death. So the opportunity for a lot of gruesome, but plausible, ends really helps to add a sense of importance and urgency to the choices a player can make.

How can interactive formats, or games, bring different experiences to bear on history?

In some ways, I’d say this question almost answers itself. It’s precisely because games allow us to experience history that they have such rich potential. Some people can read about historical places or events and naturally start imagining that landscape and constructing their own personal narrative of moving through that landscape, but most of us have a hard time doing that. Most history books, be they textbooks or academic monographs, are very flat. They’re not about individual human experiences; they’re very abstract. And they demand quite a lot of their readers. They essentially say “hey reader, you have to be already invested in what I’m about to tell you, because I’m not going to help you connect to this material on any kind of personal or emotional level.”

Now, that kind of abstraction can certainly lead us to interesting and valuable insights into the past, but it also makes history seem like it’s not about people, when, on the contrary, history is all about people. I see games as having the power to help us get back to that idea that history is someone’s lived experience of the past. Players aren’t simply told about a world or a moment, they get to explore that moment and even participate in it. And even if the personal story they end up creating diverges from any known historical realities, it still gives the player that hook for exploring the world further. Now that they’ve experienced some possible outcome, they have an incentive to start asking, “what are the other possibilities?”

It’s that unique combination of narrative and choice that can provide a really great platform for generating questions. And once that curiosity is fired up, at some point, you’ll likely find that don’t need the game anymore to be interested in history. You already have some context laid down for understanding those abstract texts. I guess you could say that I see games as having the power to be a kind of gateway drug that ultimately leads us into taking learning into our own hands!

What does ‘objective’ history miss?

I hinted at this a little bit in the previous question, but I think one of the weaknesses of professional historians’ focus on creating really detached, “objective” histories is that they end up omitting the human aspect of history. History is fundamentally a collective narrative of real human beings’ lived experiences, yet so many people see it as this dry and distant place that’s totally unfamiliar compared to our own lives and the world we live in now.

The problem is that we often only know “the facts” of an historical event: we know that someone gave a speech and we know what that speech said, or we know that bombs were dropped in a specific place at a specific time, or that a gene or virus was discovered by a particular person or lab. But rarely do we know anything about the thoughts or emotions of the people involved in those moments. And for obvious reasons, professional historians aren’t in the business of speculating or taking guesses when they have no evidence at all. Of course, that’s a very responsible way of dealing with this issue, but it’s still problematic: just because a history is objective insofar as it doesn’t speculate beyond what’s in the source material doesn’t make it a faithful representation of the past. Instead, what we’re really doing is painting a picture of the past using only one color instead of a full palette. The picture is not necessarily inaccurate, but it’s definitely incomplete. And in that respect, it simply can’t be the only way we approach doing history.

Again, this is where games can really help to fill in the bigger picture and marry the facts of the objective portrait with the narrative of personal experiences that we’ve since lost. Games give players a freedom to speculate, to imagine, and to recreate and relive the emotional and personal experiences that conventional histories must necessarily shy away from. And it’s only through that historical imagination that I think we can bring ourselves closer to having true knowledge and understanding of the past.

And an understanding of what it’s like to die in a snake pit! What we at The Appendix love about “The Fever” is that it’s not just interesting, and empathetic, but it’s also unexpectedly funny, and captures the spirit of those great ‘counterfactual’ fictions, Choose Your Own Adventure. Did you have a personal favorite, growing up?

Funny that you should bring up the snake pit—that scenario is the only part of my story that wasn’t actually my idea at all! I was telling some friends about this project, and their first question to me was “does it have a snake pit? These stories always have to include a snake pit!” But I was very resistant to anything like that at first, mainly because I don’t recall having a favorite story Choose Your Own Adventure story, but I do vividly remember how frustrated I would get when a scenario became overly absurd. Like when you would get to one of those moments when you can sense you’re about to make a life or death decision, but the story hadn’t given you any context for making a good decision. And if you’re me, when you get to that point you’re thinking to yourself, “neither of these choices makes any sense! Why can’t I just run away?”

But I eventually came to realize that silliness and absurdity does have a place in these kinds of choice-driven narratives. The trick is figuring out when and how to bring in that playfulness in and when to play it straight. If you let whole scenarios become too bizarre, then yes, it can easily become frustrating to readers because they don’t feel in control of their character’s fate anymore. But game designers know that people love surprises, and the best games are the ones than know when to bend or stretch the rules just a little to create those little unexpected twists. If done right, those surprises are the very thing that keep us coming back for more. So now I’m completely sold on the idea: always have a snake pit! QED.