Interpreting “Physick”: The Familiar and Foreign Eighteenth-Century Body

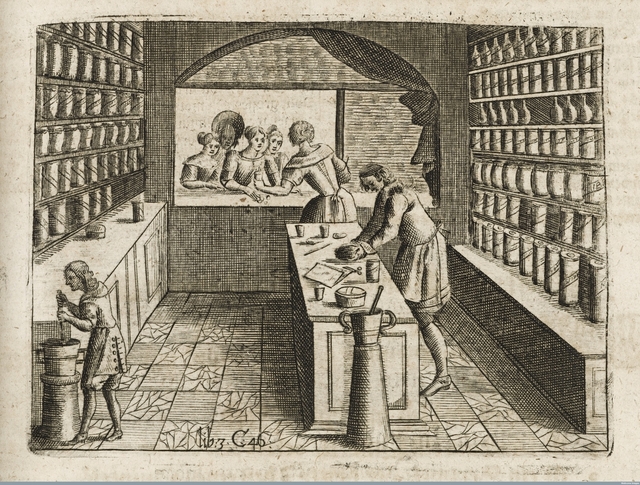

A recreated apothecary shop in Alexandria, Virginia, is representative of the style and organization of eighteenth-century shops. Wikimedia Commons

Aspirin. It’s inevitable.

When asked what medicine they’d want most if they lived in the eighteenth century, the visitors will struggle in silence for few moments. Then, someone will offer, “Aspirin?” Sometimes it’s delivered with a note of authority, on the mistaken notion that aspirin is derived from Native American remedies: “Aspirin.” I modulate my answer depending on the tone of the question. If the mood feels right, especially if the speaker answers with a note of condescension, I’ve been known to reply, “Do you know anyone who’s died of a mild headache?”

I work as an interpreter in the apothecary shop at the largest living history museum in the US.

If visitors leave with new knowledge, I’m satisfied. Another hundred people will remember the next time they make a meringue that cream of tartar is a laxative. But what I really want them to come away with is an idea. I want visitors to understand that our eighteenth-century forbears weren’t stupid. In the absence of key pieces of information—for examples, germ theory—they developed a model of the body, health, and healing that was fundamentally logical. Some treatments worked, and many didn’t, but there was a method to the apparent madness.

This seventeenth-century engraving shows medicines being compounded and dispensed. Women were not licensed as apothecaries in the eighteenth century, but evidence suggests that in England, at least, they sometimes assisted husbands and fathers, despite not being licensed. Wolfgang Helmhard Hohberg’s Georgica Curiosa Aucta (1697) via Wellcome Images

Most visitors are mildly alarmed to learn that there was nothing available for mild, systemic pain relief in the eighteenth century. You’d have to come back next century for aspirin. Potent pain management was available via opium latex, often mixed with wine and brandy to make laudanum. In the eighteenth century, small amounts were used as a narcotic, a sedative, a cough suppressant, or to stop up the bowels, but not for headaches.

There were headache treatments, however. Colonial medical practitioners recognized multiple types of headaches based on the perceived cause, each with its own constellation of solutions. As is often the case, the simplest solutions were often effective. For a headache caused by sinus pressure, for example, the treatment was to induce sneezing with powered tobacco or pepper. Some good, hard sneezing would help expel mucus from the sinuses, thus relieving the pressure. For “nervous headaches”—what we call stress or tension headaches—I uncork a small, clear bottle and invite visitors to sniff the contents and guess what the clear liquid inside could be.

With enough coaxing, someone will recognize it as lavender oil. While eighteenth-century sufferers rubbed it on their temples, those with jangling nerves today can simply smell it—we don’t understand the exact mechanism, but lavender oil has been shown to soothe the nervous system. As a final example, and to introduce the idea that the line between food and medicine was less distinct two hundred years ago, I explain the uses of coffee in treating migraines and the headaches induced after a “debauch of hard liquors.” Caffeine is still used to treat migraines because it helps constrict blood vessels in the head, which can reduce pressure on the brain.

But if your biggest medical concern in the eighteenth century was a headache, you were lucky. Eighteenth-century medical practitioners faced menaces like cholera, dysentery, measles, mumps, rubella, smallpox, syphilis, typhus, typhoid, tuberculosis, and yellow fever. Here are a few.

Malaria

The bark of the cinchona tree, called Peruvian bark or Jesuits bark, was an important addition to the European pharmacopeia. Wikimedia Commons

In discussing larger threats, I generally choose to focus on an illness that many visitors have heard of before, and for which a treatment was available. The “intermittent fever” also gives visitors a glimpse of one of the difficulties of studying the history of medicine–vague and often multiple names for a single condition. Intermittent fever was called such because of a particular symptom that made it easier to identify among a host of other fevers–sufferers experienced not only the usual fever, chills, and fatigue, but also paroxysms: cycles of intense chills followed by fever and sweating. Severe cases could result in anemia, jaundice, convulsions, and death.

After describing the symptoms to guests, I mention that the disease tended to afflict those living in swampy, hot, low-lying areas—such as Williamsburg. Older visitors often put it together—intermittent fever is what we call malaria. And typically, they know the original treatment for malaria was quinine.

It’s one of the times I can say, “We have that!” rather than, “Give us another hundred years.” I turn to the rows of bottles on the shelf behind me—not the eighteenth-century original apothecary jars that line the walls, but a little army of glass bottles, corked and capped with leather. The one I’m looking for is easy to find—a deep red liquid in a clear glass bottle. As I set it on the front counter, I introduce the contents: “Tincture of Peruvian bark.” I tend to add, “This is something I would have in my eighteenth-century medical cabinet.” Walking to the rear wall, I pull open a drawer and remove a wooden container. I lift the lid to reveal chunks of an unremarkable-looking bark. I explain that the bark comes from the cinchona tree, and, as undistinguished as it looks, it was one of the major medical advances of the seventeenth century.

Also called Jesuits’ bark, cinchona was used as a fever-reducer by native peoples in South America before being exported by the Jesuits to Europe. Its efficacy in fighting fevers soon made it a staple in English medical practice. While eighteenth-century apothecaries were ignorant of quinine, which would not be isolated and named until the 1810s, they were nonetheless prescribing it effectively.

The rings and dark dots are the result of infection by Plasmodium falciparum, one of the strains of protozoa that cause malaria. Wikimedia Commons

I make a point of explaining to visitors that quinine does not act like modern antibiotics do in killing off infections directly. Malaria is neither bacterial nor viral, but protozoan. Quinine (and more modern drugs derived from it and increasingly from Chinese Artemisia) interrupts the reproductive cycle of the malaria protozoa, halting the waves of offspring that burst forth from infected red blood cells. The protozoa, now rendered impotent, hole up in the sufferer’s liver, often swarming forth later in life in another breeding bid. So technically, once infected, you’ll always have malaria, but can suppress the symptoms.

Peruvian bark was used to treat a wide range of fevers, but it was not the only treatment. In certain instances of fever, it was used in conjunction with bloodletting. Bloodletting is a practice I’m always eager to explain, because it is so revealing of just how much our understanding of the body has changed in two centuries. Plus it freaks people out.

Fevers: A Note on Phlebotomy

Bloodletting or phlebotomy, dates back to antiquity. In the humoral theory of the body promulgated by Greco-Roman physicians, removing blood promoted health by balancing the humors, or fluids, of the body. This theory prevailed from roughly the fourth through the seventeenth centuries. Medical theorists gradually adopted a more mechanical understanding of the body, inspired by a renewed interest in anatomy and by experiments that explored the behavior of fluids and gases. These new theories provided an updated justification for bloodletting in particular cases.

Whereas bloodletting had been a very widely applied treatment in ancient times, eighteenth-century apothecaries and physicians recommended it in more limited cases. In terms of fevers, it was to be applied only in inflammatory cases, which were associated with the blood, rather than putrid or bilious fevers, which were digestive. In Domestic Medicine, a popular late-eighteenth century home medical guide, physician William Buchan warned that “In most low, nervous, and putrid fevers … bleeding really is harmful … . Bleeding is an excellent medicine when necessary, but should never be wantonly performed.”

Eighteenth-century medical professionals believe that acute overheating often brought on inflammatory fevers. Key symptoms of inflammatory fevers were redness, swelling, pain, heat, and a fast, full pulse. Anything that promoted a rapid change in temperature, such as overexertion or unusually spicy food, could set off a chain reaction that resulted in inflammation. Drawing on mechanical theories of the body and renewed attention to the behavior of fluids, doctors complicated simple humoral explanations of disease. Blood, as a liquid, was presumed to behave as other liquids did. When heated, liquids move more rapidly; within the closed system of the human body, overheated blood coursed too rapidly through the body, generating friction. This friction in turn generated more heat and suppressed the expression of perspiration and urine, which compromised the body’s natural means for expelling illness. Removing a small quantity of blood, doctors reasoned, would relieve some of the pressure and friction in the circulatory system and allow the body to regulate itself back to health.

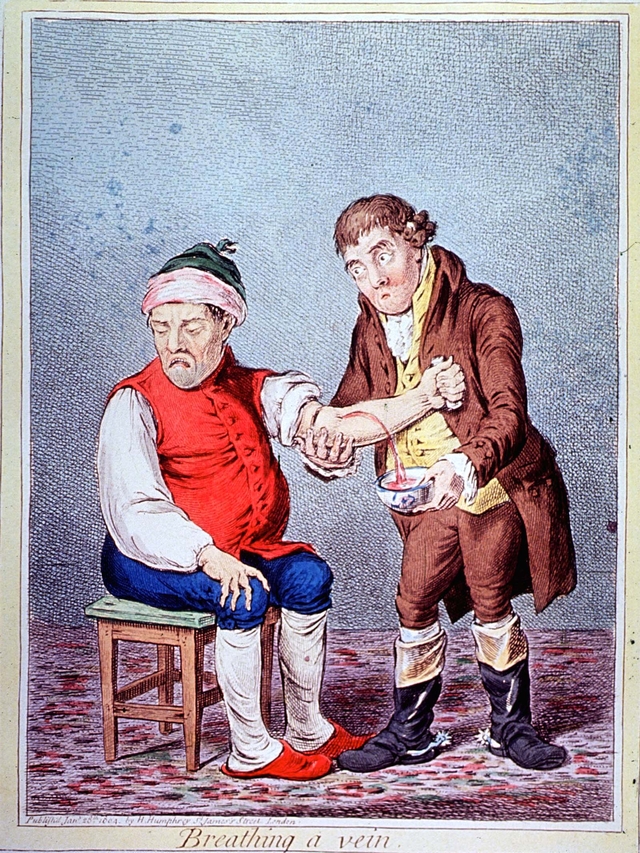

Picking up the lancet, I roll up my sleeve and gesture to the bend of my elbow, where blue veins are faintly visible through my skin. Generally, I explain, blood was let through these veins by venisection, where the lancet—a small pointed blade that folds neatly into its wooden handle like a tiny Swiss Army knife—is used to make a small incision below a fillet—a looped bandage tightened on the upper arm to control blood flow. The process is akin to blood donation today, except that the blood removed will be discarded. Apothecaries and physicians, striving to be systematic and scientific, often caught the escaping blood in a bleeding bowl—a handled dish engraved with lines indicating the volume of the contents in ounces. The volume of blood removed, Buchan cautioned, “must be in proportion to the strength of the patient and the violence of the disease.” Generally, a single bloodletting sufficed, but if symptoms persisted, repeated bloodlettings might be advised.

Visitors are generally incredulous that the procedure was fairly commonplace, and that people did it in their homes without the supervision of a medical professional. Bloodletting was sometimes recommended to promote menstruation or encourage the production of fresh blood. Both published medical writings and private papers suggest that folk traditions of bloodletting for a variety of reasons persisted throughout the eighteenth century.

Modern guests question both the safety and the efficacy of bloodletting. It terms of safety, it was generally a low-risk procedure; one function of bleeding was to push pathogens out of the body, thus limiting the risk of blood-borne infections. Routine bloodletting was typically limited to six or eight ounces of blood. By comparison, blood donors today give sixteen ounces. The human body is actually fairly resilient and can withstand substantial blood loss, so even in acute cases where blood was repeatedly let, exsanguination was unlikely to be the cause of death. One famous case visitors sometimes bring up is the death of George Washington in December 1799. While it is difficult to know the circumstances precisely, Dr. David Morens with the National Institutes of Health argues that the first President was afflicted with acute bacterial epiglottitis. The epiglottis is the small flap that prevents food from entering the airway or air from entering the stomach; when it becomes infected it swells, making eating, drinking, and breathing increasingly difficult, and eventually impossible. According to notes taken by the trio of physicians who treated Washington, he endured four bloodlettings in twelve hours, removing a total of 80 ounces of blood—the limit of what was survivable. This aggressive treatment presaged the “heroic” medicine of the nineteenth century and was far out of line with the recommendations of earlier physicians such as Buchan. Even so, Morens suspects that asphyxiation, not bloodletting, was cause of death.

Thus, while bloodletting probably caused few deaths, it also saved few lives. Aside from a possible placebo effect, bloodletting’s primary efficacy is in treating rare genetic blood disorders such as polycythemia (overproduction of red blood cells) and hemochromatosis (an iron overload disorder). So while the logic behind bloodletting seemed reasonable, it was due to the lack of a critical piece of information. “What actually caused most of the diseases doctors tried to treat with bloodletting?” I’ll ask. “Germs!” a visitor calls out. “Unfortunately,” I reply, “it will be another seventy-five years until the medical establishment accepts that we’re all covered in microscopic organisms that can kill us.”

The Common Cold

Most medical recommendations weren’t so seemingly bizarre, however. Eighteenth-century doctors strove to “assist Nature” in battling disease by recommending regimens—modifications of behavior, environment, and diet that were thought to promote recovery. Doctors and caretakers induced vomiting (an “upward purge”), defecation (a “downward purge”), urination, and/or sweating to help the body expel harmful substances and offered diets that were thought to help warm, cool, or strengthen the body. When visitors ask when the most commonly prescribed medicine is, we can’t give them a direct answer—the apothecaries kept track of debts and credits but not what was purchased—but we tell them the most common category of medicine we stocked was a laxative. Keeping one’s digestion regular was a priority in the eighteenth century.

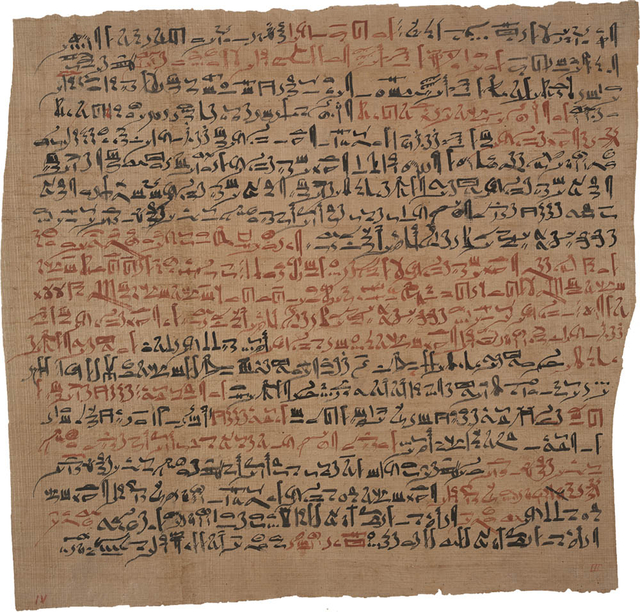

The common cold has been with humanity for a very long time: it was described as far back as 1,550 BCE, in the Egyptian medical text known as the Ebers Papyrus. Wikimedia Commons

Visitors are often surprised to hear that they unwittingly follow regimens themselves, often for the same common ailments that laid low our colonial and revolutionary forbears. The example I typically use is the common cold, for which there is and never has been, alas, a cure. Looking to the row of children typically pressed up against the counter, I ask, “When you’re sick and can’t go to school, do you get more rest, or more exercise?” “Rest,” they answer in chorus. “And where do you rest?” “In bed.” “And what do you eat a lot of when you’re sick?” “Soup” and “juice” are the usual answers. “You’re behaving much as you would have two hundred and fifty years ago!” I tell them. “Doctors recommended resting someplace warm and dry and eating foods that were light and easy to digest—including broths and soups.”

Visitors are fascinated and often charmed to hear that the treatment of colds has essentially stayed the same. “When you take medicine for your cold,” I continue, “does it make you feel better or make your cold go away?” Most people are dumbfounded when they consider that the majority of medicine in the eighteenth century and today are to alleviate symptoms. Then as now, individuals and households selected treatments for stuffy noses, coughs, and fevers.

Surgery

While the treatment of disease has aspects both foreign and familiar, our distance from our forbears truly comes across in the comparatively primitive levels of surgery and midwifery. Because the squeamishness of guests varies widely, and because interpreters are discouraged from inducing nausea or fainting, we must proceed cautiously.

Surgery, visitors are shocked to hear, was not a prestigious profession until recently. In the eighteenth century, any physical undertaking for medical purposes was surgery—bandaging, brushing teeth, bloodletting. While separate in England, in the colonies apothecaries often took on surgical duties; low population density generally prevented specialization outside of large cities. In England, surgeons shared a guild (professional organization) with barbers, who pulled teeth and let blood as well as grooming and styling hair. A surgeon’s purview was more expansive—they set broken bones, amputated extremities when necessary, and removed surface tumors, requiring greater knowledge of anatomy.

Simple breaks could be set manually, as they are today. I often use myself as an example—I have an approximately fifteen-degree angle in my wrist from a bad fall several years ago. I explain that my wrist was set manually, with no pain management, very much as it might have been in the eighteenth century. (You know you’re a historian when that’s what you’re thinking on the gurney as a doctor jerks your bones back into alignment.)

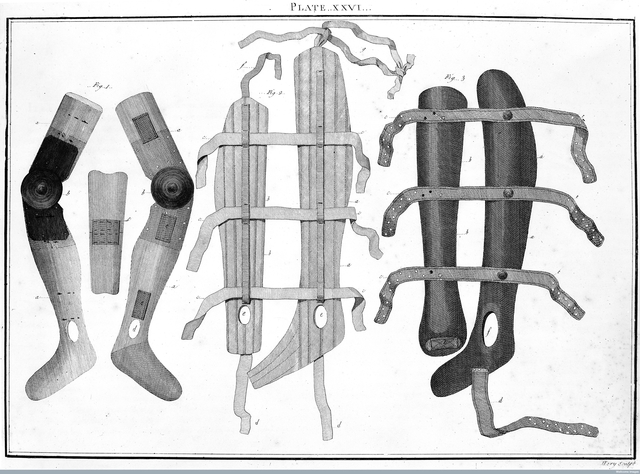

Before plaster casts were developed in the nineteenth century, broken bones could only be splinted. This engraving shows more elaborate splints for broken legs. Wellcome Images

Two factors limited the scope of surgical operations in the eighteenth century. The first was the lack of antisepsis; with no knowledge of germ theory and thus little control for infections surgeons avoided guts and kept operations as simple and efficient as possible. The second was pain.

A visitor always asks, “What did they do for pain?” Upon being told, “Nothing,” they blanch and then argue.

“What about opium?”

“Opium makes you vomit, and you’re restrained during operations and often on your back. You wouldn’t want to choke to death during your surgery.”

“They had to have done SOMETHING! A few shots of whiskey at least.”

While we can’t be sure what people did at home or while waiting for the doctor to arrive, doctors opposed the consumption of spirits before surgery because of increased bleeding. Occasionally, a visitor will ask if patients were given a thump on the head to make them lose consciousness.

“Well, the pain will probably wake you up anyhow,” I point out, “and now you have a head injury as well as an amputation to deal with.”

Generally, amputations lasted less then five minutes—minimizing the risk of infection and the chances of the patient going into shock from blood loss and pain. Limbs weren’t simply lopped off, however. Surgeons could tie off large blood vessels to reduce blood loss, and the surgical kit we display shows the specialized knives, saws, and muscle retractors employed by surgeons to make closed stumps around the severed bone.

Removing troublesome tumors was another challenge surgeons faced, commonly from breast cancer. This surprises some visitors, who tend to think of cancer as modern disease. I’ve even had a visitor insist that there couldn’t have been cancer two hundred years ago, when there were no chemical pesticides or preservatives. I informed him that cancer can also arise from naturally occurring mutations or malfunctions in cells—it even showed up in dinosaurs. Mastectomies have been performed for thousands of years. Because there was no means of targeting and controlling tumors, aggressive growth sometimes cause ulcerations through the skin, causing immense pain and generating a foul smell. Medicines such as tincture of myrrh were available to clean the ulcers and reduce the smell but did nothing to limit the cancer’s growth.

When ulceration made the pain unbearable or the tumor’s size interfered with everyday activities, sufferers resorted to surgery. Surgeons sought to remove the entire tumor, believing that if the cancer were not rooted out entirely, it would strike inward where they could not treat it. They were half right; cancer is prone to reappearing elsewhere in the body. Unfortunately, the removal of tumors triggers this—tumors secrete hormones that prevent the proliferation of cancer cells in other areas of the body. Removing tumors unleashes dormant cancer cells that have been distributed throughout the body. Without antisepsis and anesthesia, surgeons could not follow cancer inward.

Midwifery

Childbirth was one mystery partially penetrated in the eighteenth century. Prominent British physicians turned their attention to the anatomy and physiology of fetal development and conducted dissections—perhaps made possible by trade in freshly murdered cadavers in major British cities.

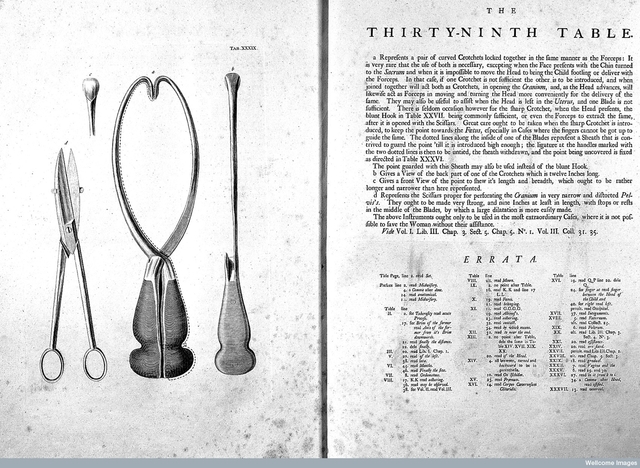

Illustration of fetal development in William Smellie’s Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Midwifery. Wellcome Images

William Smellie, a Scottish physician, produced some of the most accurate illustrations and descriptions of birth then available. Smellie’s Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Midwifery promoted the presence of male doctors into the traditionally sex-segregated birthing room. European medical schools began offering lecture series in midwifery leading to a certificate. The vast majority of women, especially in rural areas, continued to be delivered by traditional female midwives, but man-midwives were newly equipped to handle rare emergencies in obstructed delivery. Obstetrical forceps became more widely available over the course of the eighteenth century, though they were still cause for alarm; Smellie recommended that “operators” carry the disarticulated forcep blades in the side-pockets, arrange himself under a sheet, and only then “take out and dispose the blades on each side of the patient; by which means, he will often be able to deliver with the forceps, without their being perceived by the woman herself, or any other of the assistants.”

You can read more about Smellie’s inventions and early modern birthing devices in Brandy Shillace’s Appendix article “Mother Machine: An Uncanny Valley in the Eighteenth Century.”

In the shop, we rarely talk about the other equipment male doctors carried, for fear of upsetting visitors or creating controversy. Men continued to carry the “destructive instruments” long used to extract fetuses in order to save the mother. With forceps man-midwifery moved in the direction of delivery over dismemberment, but it remained an inescapable task before caesarean sections could be performed safely. Despite this avoidance, it periodically pops up, and forces me as the interpreter to rely on innuendo. One particularly discomfiting instance involved an eleven-year-old girl who asked about babies getting stuck during delivery. After explaining how forceps were used, she asked, “What if that didn’t work?” The best I could come up with was, “Then doctors had to get the baby out by any means necessary so the woman wouldn’t die.” She sensed my evasion and pressed on—“How did they do that?” Unwilling to explain how doctors used scissors and hooks in front of a group including children, I turned a despairing gaze on her mother. Fortunately, she sensed my panic and ushered her daughter outside; what explanation she offered, I do not know.

Most women, fortunately, experienced uncomplicated deliveries and did not require the services of a man-midwife. Birth was not quite so fraught with peril as many visitors believe. While I’ve had one visitor inform me that all women died in childbirth, human reproduction generally works quite well. American colonists enjoyed a remarkably high birthrate. While there were regional variations, maternal mortality was probably about two percent—roughly ten times the maternal mortality rate in the United States (which lags significantly behind other developed countries). Repeated childbearing compounded these risks; approximately 1 in 12 women died as a result of childbearing over the course of their lives. Childbirth was a leading cause of death for women between puberty and menopause.

Improvements in antisepsis, prenatal care, fetal and maternal monitoring, and family planning over the past two centuries have pulled birth and death further apart. Fear of death altered how parents related to infants and children, how couples faced childbearing, and reproductive strategies. While this fear persists today, it is far more contained than it was two centuries ago.

Americans today live in a world of medical privilege unimaginable to their colonial forbears. It’s not because we are smarter or better than we were two hundred and fifty years ago. We are the beneficiaries of a series of innovations that have fundamentally altered how we conceptualize the body and reduced once-common threats. Guests in the Apothecary Shop today think of headaches as their most frequent medical problem because so many pressing diseases have been taken off the table.

From this privileged perspective, it’s all too easy to look down on those who believed in bloodletting or resorted to amputation for broken limbs. But the drive to do something to treat illness, to seek explanations for disease as a means of control, to strive to hold off death—these impulses haven’t changed.

As I often tell visitors—give it two hundred and fifty years, and we’ll look stupid too.