The History of Mana: How an Austronesian Concept Became a Video Game Mechanic

On January 17, 2007 the dimensional ship Exodar crash-landed on Azuremyst Isle, just off the northwest coast of Kalimdor. Amidst the suffering and wreckage, the survivors took stock of the new world they had found a land—which was, like them, part of the on-line video game World of Warcraft. They were draenei, an uncorrupted race of Eredar that had been added to the game as part of its Burning Crusade expansion pack. I decided to play one, mostly because I was getting tired of playing dwarves and elves. I named him Izzycohen and taught him how to make jewelry.

Two years later Izzycohen had become a mighty shaman, a healer who aided his allies in battle by casting healing rays of light that the guys I played online with called ‘Jesus Beams.’ The Naga Warlord Naj’entus kept killing us, however, and so I spent about two hours adjusting my armor to make my healing spell a tenth of a second faster (because, trust me, one tenth of a second is a long time in World of Warcraft). When I say ‘my armor,’ what I really mean is a spreadsheet I used to analyze every piece of armor my character wore. Each piece of gear—the helmet, the chest piece, the chainmail legs—altered my character’s powers. My goal was to increase the amount of ‘Haste’ he had without giving up too much mana.

Spellcasters rely on mana. In World of Warcraft, mana is a magical energy possessed by druids, mages, paladins, priests, shamans, and warlocks, which is measured in points. Different spells cost different amounts of points. Much of the game mechanic revolves around managing and using mana wisely: casting spells often enough to achieve your goal, but not so often that you run out of mana early. Characters that go ‘oom’ (‘out of mana’) can no longer help their friends, and are helpless if attacked. Characters can replenish their mana by eating mana strudel and mana biscuits. Mana oil can be applied to weapons to increase the rate that their bearers regenerate it. Mana looms are required to weave enchanted cloth. Magical beasts such as mana leeches and mana serpents roam the land, ready to prey on spellcasters.

But mana, unlike ‘draenei,’ is not something that the designers of WoW invented whole cloth. Like ‘tattoo,’ ‘taboo’ and ‘tiki,’ ‘mana’ is a word from the Polynesian branch of the Austronesian language family. In twenty-seven of these languages, the word mana means something like ‘supernatural power.’ Pacific Island cultures are the origin of the concept of mana, and yet more people in the world have learned about the concept from WoW or other fantasy games. At its height, there were more players of World of Warcraft than Pacific Islanders: there were ten million players worldwide in North America, Europe, Latin America, and China (among others). At this time there were only about 6.7 million people in the combined population of Tonga, Fiji, Samoa, Vanuatu, New Zealand (including Pakeha, or white, Kiwis), and all the Pacific Islanders in the US. And Warcraft is really just the start. The concept is a staple of the global culture of fantasy novels and video games, many of which feature a blue bar of magical energy called ‘mana.’

But how did this happen? How did a concept from Pago Pago become part of global gaming culture? How did an Austronesian spiritual force come on board the Exodar, and become part of the life of my draenei shaman? To answer this question we have to return to the Pacific, and to the Austronesians themselves.

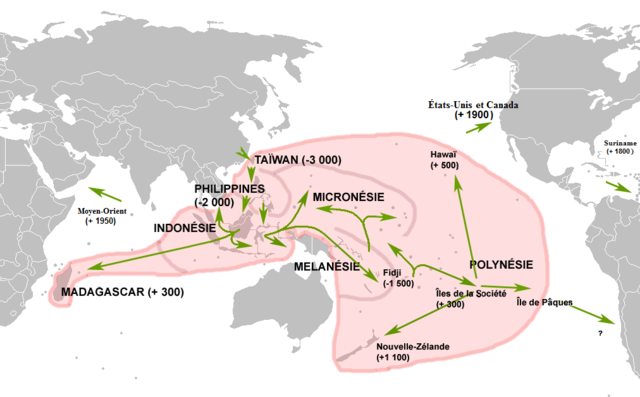

We first catch sight of them 5,500 years ago. We call them ‘the Austronesians’ because that’s the name we’ve given to the language we think they spoke. Just as French, Greek, and Hindi share the common ancestral language of Indo-European, the native people of Taiwan, island Southeast Asia, some of mainland Southeast Asia, Madagascar, and much of the Pacific speak Austronesian languages. And just as anthropologists and linguists have reconstructed Indo-European culture (the chariots, the sacrifices, the epic poetry) so too have they pieced together a coherent picture of the Austronesians. Like the Indo-Europeans, they liked to travel. Around four thousand years ago Austronesian speakers began expanding outward from their homeland in Taiwan, moving south and west in voyages that make Indo-European migration seem puny. Austronesians were seafarers, building rafts and canoes capable of breathtaking journeys. Some expanded west as far as modern day Mozambique and settled Madagascar. Mostly they moved east: across Indonesia, the New Guinea mainland, through Vanuatu and the way to New Zealand and Hawai‘i. They eventually reached the Americas, bringing back sweet potato and calling it ‘kumara’, borrowing the name from American Indian languages. They were probably matrilineal, reckoning descent through women rather then men. The made amazing pottery decorated with human figures, and imagined their leaders to be strangers of great power who came from far away. In fact, we know an amazing amount about them—unless we don’t. Although most people have never heard about it, the world of Austronesianists can be disputatious.

A map of the remarkably rapid expansion of Austronesian languages. Wikipedia user Maulucioni, based on previous work by Christophe Cagé

One of the things we do know is that as they headed out into the Pacific, they brought the word ‘mana’ with them. Its origin is lost in the mists of time, although the linguist Robert Blust has argued the word originally meant ‘powerful wind,’ ‘lightning,’ or ‘storm’—as it indeed still does in some languages. From there, he argues, it seems likely that the term shifted meaning and kept the sense of power and efficacy while losing its primary meteorological referent. Aram Oroi, a pastor and theologian from the island of Makira in the Solomon Islands, says that mana is like a flashlight being turned on. You sense something powerful but unseen, and then—click—its power is made manifest in the world.

It took centuries for Europeans to catch up with Austronesian-speaking people in their exploration of the Pacific. When they did, they were astounded. In 1769, James Cook made his way to Tahiti, where he met Tupaia, a Rai‘atean nobleman who was “the Machiavelli of eighteenth century Tahiti.” Europeans like Cook knew little about the geography of the Pacific, so Tupaia made Cook a map of the Pacific with over fifty islands on it. He then proceeded to journey with Cook, leading him to New Zealand, where he served as interpreter. On this and other trips Europeans were gobsmacked. How could people living thousands of miles from each other, across huge expanses of open ocean, speak languages as closely related as French or Spanish? How could they navigate to these islands without clocks or sextants? What they had not yet realized—what would take many years to grasp—was that the ocean was something that connected Pacific Islanders, rather than separating them.

Those European attempts to understand the Pacific were at first racist and ham-fisted. In 1832 the French nobleman Durmont D’urville divided the Pacific into three realms: Polynesia, Micronesia, and Melanesia. Melanesia—literally where the black people lived—was seen as the most savage, while the more lightly-complected Polynesians of Hawai‘i, New Zealand, and Tahiti were considered more civilized. Micronesia was pretty much was everything that was left over. We still use these categories today, despite their conceptual inadequacy. Austronesian languages and cultures, for instance, can be found in all three areas. Mana crosses the lines Europeans drew.

J. G. Barbie du Bocage’s 1852 map of Oceania, showing the tripartite division typical of early European attempts to understand the languages and cultures of the Pacific. Wikimedia Commons

Over time Europeans slowly began to understand the languages and cultures of Polynesia, which had a relatively simple and short history of migration. Further west, however, more mysteries beckoned. ‘Melanesia’ had seen human habitation for 40,000 years, and its mixture of cultures, languages, and genes is much more complex.

One of the first people to study this area was Robert Henry Codrington. Codrington was born in 1830 England to a long line of Anglican clergymen, and became one himself after passing through Charterhouse and Oxford, two of England’s most elite institutions. In 1867 he moved to Norfolk Island, off the coast of Australia, to begin service with the Melanesian Mission.

Founded in 1849, the Mission’s goal was to spread Christianity and Civilization to the southwest Pacific, especially what is known as ‘Island Melanesia’—Vanuatu, the Solomon Islands, and the Bismark archipelago and bits of the New Guinea mainland. By today’s standards the Misson’s self-confidence may rankle, but compared to other Victorian colonial projects it was very well-behaved: the goal was to civilize, but the missionaries treated Melanesians as equals—by which was meant that it assumed that they could, with practice, act with the decency and commonsense of Englishmen. Most importantly, the Mission felt that conversion should not be rushed. Local cultures had to be learned and local languages carefully studied, perhaps for decades, before they could be understood. In fact, the main goal was to train Pacific Islanders to act as evangelists in their home communities.

When Codrington arrived at Norfolk Island in 1867, his job was to run the school where potential evangelists would be taught. But Codrington did more than that. For the next twenty years he was the island’s jack of all trades. He was the chief cook of the school, and produced plum puddings for the marriage feasts of his students. He dabbled in architecture, designing a dining hall for the school, and worked as a stone mason, finishing marble columns for the church on the island (“I never tried to carve stone & am afraid” he wrote in a letter). He learned how to print books, take photographs, and teach people to play the harmonium. Eventually, he served as the head of the mission from 1871 to 1877 before retiring to England.

Europeans had been sniffing around Melanesia for over a century by the time that Codrington had gotten there, but few had spent as much time as he had living and working alongside Melanesians. Fewer still had travelled across the region the way he had, and none were as hell bent on spending their retirement as a gentleman scholar producing a massive ethnographic work about their experiences. Codrington’s masterpiece, The Melanesians: Studies in their Anthropology and Folk-Lore appeared in 1891. One of the ideas that he had ‘discovered’ was mana.

“The Melanesian mind is entirely possessed by the belief in a supernatural power or influence, called almost universally mana,” wrote Codrington in The Melanesians:

This is what works to effect everything that is beyond the ordinary power of man, outside the common processes of nature; it is present in the atmosphere of life, attaches itself to persons and to things, and is manifested by results which can only be ascribed to its operation. The word is common I believe to the whole Pacific… It is a power or influence, not physical, and in a way supernatural; but it shews itself in physical force, or in any kind of power or excellence which a man possesses… All Melanesian religion consists, in fact, in getting this Mana for one’s self, or getting it used for one’s benefit.

Codrington’s work generated tremendous excitement amongst its the late-Victorian audience. Codrington’s expertise was unimpeachable: he was a careful thinker with decades of experience in Melanesia and (of course) an Oxford man. Moreover, his book was one of the first ever written about Melanesia: there was no competition. But there was more to it then that. By the late 1890s European knowledge of the world was growing in leaps and bounds. Philology and archaeology had revealed thousands of years of history in the ancient Near East that predated the world described in the Hebrew Bible. Missionary and ethnological work provided accounts of ‘religious’ beliefs (for so were they labeled) of colonial subjects. And translations of Buddhist, Hindu, and Confucian texts—as these traditions came to be labeled in the West—revealed an entire world of thought whose antiquity and complexity made Christendom blush.

A synthetic story of human civilization seemed within reach: a single, authoritative, scientific account of the development of civilization, from the lowliest savages to the highest peaks of civilization—by which Europeans meant, of course, themselves. As Europeans went about the job of deciding just how far beneath themselves other people were, Codrington’s concept of mana took on a new significance. Could mana represent the most basic, embryonic form that religion could take? Could it be the seed out of which Christianity would eventually spring? Could this belief in a universal spiritual force be similar to the concepts of orenda, zemi, and oki found in other regions as far away as Native North America? Was there in fact a universal human awareness of a generic cosmic force?

The answer, we now know, is ‘no.’ Under closer scrutiny it became clear that the idea of mana as the universal and most primitive experience of the sacred is crap.

And yet ‘mana’ as the universal, primitive experience of the sacred persists in popular culture today, from Star Wars’ “The Force” to Max Long’s fake-Hawaiian New Age religion of ‘huna’. How could the concept of mana as a generic spiritual force become invalidated and ubiquitous at the same time?

One answer can be found in the story of Mircea Eliade. Born in Romania in 1907, Eliade began his academic career studying the philosophy of Renaissance Italy. A detour took him to India, where he studied South Asian languages and Indian philosophy, eventually producing a Ph.D. dissertation on yoga in 1933. Throughout the 1930s and 40s, Eliade lived as an intellectual and writer in Romania, inadvertently spawning numerous Wikipedia edit wars by possibly—or possibly not—becoming a fascist. By the end of World War II Eliade had washed up in France, where he had a position at the École Pratiques des Hautes Études. It was there that he wrote the two works that presented his master philosophy: The Myth of the Eternal Return and Patterns in Comparative Religion.

Eliade’s work fixated on the thresholds between the sacred and the profane, focusing on concepts like the Norse world tree Yggdrasil (pictured here in a seventeenth-century manuscript illustration) and mana, which bridged the ineffable spiritual and material realms. Wikimedia Commons

Eliade believed that all humans had a fundamental experience of the sacred: an a-cultural unmediated experience of the divine which he called ‘hierophany.’ But because the divine was overwhelmingly powerful and incomprehensible, no human being could fully grok it. Rather, Eliade argued, our experience of the divine is shaped by our culture, which filters it and makes it comprehensible. Eliade proposed a global comparative study of the culturally distinct shaping of hierophany. In it, mana was ‘kratophony’, the experience of divinity as power, not a primitive or backward concept, but merely one among many. This was the genius of Eliade’s framework: It was a new humanism, like the humanism of Renaissance Italy, but one that respected all cultures and treated them equally. It was be an entire academic discipline, one dedicated to documenting the history of human spirit. And, conveniently, it was a discipline that could be overseen and administered by Eliade himself.

Eliade’s chance to realize his goals came in 1956 when he was hired at the University of Chicago. There, Eliade used his position at the Divinity School to become a hegemonic force. He trained graduate students, founded an academic journal, wrote an ambitious three-volume synthesis of the history of religious ideas, edited an encyclopedia, and published an anthology of readings for classroom use which included, among other things, Codington’s writings on mana.

Eliade embraced the massive growth of cheap paperbacks that flourished in the United States after World War II. Series such as Harper Collins’s “Torchbook” specialized in publishing books for the rapidly-expanding college market, and Eliade churned out volume after volume, repeating the themes of his earlier writings. These were in turn re-anthologized by Eliade’s students and followers. It would be a stretch to call this an Eliade industry. But not much of a stretch.

His timing was perfect. In the late 1950s a massive bolus of baby boomers was slowly being pushed through the American education system and out into the counterculture. These young people were looking for strange new worlds to replace the square one they had grown up in. Psychedelia famously provided a way to explore inner space, but young Americans began looking outside their country for cosmic assistance as well. Intellectuals such as Victor Turner and Joseph Campbell were widely read. Eliade was just a small part of this cultural movement, but he was a key part for our story because he was one of the few academics who read about the Pacific and wrote about mana—a concept that might otherwise have disappeared in the deluge of European and Asian cultural material being consumed by the baby boomers.

And consume it they did—especially in California, where mana made the leap from the counterculture to gaming. Alan Watts wrote The Way of Zen in 1957, introducing the United States to Japanese Buddhism. The San Francisco Zen Center was founded in 1962, as was the Esalen Institute at Big Sur. Timothy Leary published The Psychedelic Experience in 1964. In 1965 Lord of the Rings was published in paperback in the United States, beginning decades of Tolkienmania and legitimating the burgeoning but disrespected genre of fantasy fiction. In 1966 the “psychedelic medivealism” of the San Francisco Bay Area gave birth of the Society for Creative Anachronism—the same year the Beatles began producing psychedelic music and George Harrison introduced fans to the raga.

This was world that received Dungeons and Dragons when it first appeared in 1974. The first modern role playing game, D&D’s key innovation was to combine the rule systems of tabletop wargaming with the setting of fantasy fiction and the interpersonal improvisation and role-playing that had been percolating in gaming and fan communities for years. D&D would fundamentally shape all future video games, role playing games, science fiction and fantasy, and global popular culture more generally. Its influences ricochet across recent cultural history like twenty-sided dice in a rolling tray. Even in the backlash it was powerful: the anti-D&D made-for-TV movie Monsters and Mazes, for instance, was one of Tom Hanks’s first leading roles and helped lead him to megastardom.

Mana did not make it into the D&D rulebook because Gary Gygax and the other creators of D&D based their magic system on the novels of Jack Vance, where a limited number of spells could be memorized, cast once, and then forgotten. But it didn’t matter. The gaming and fantasy world that gave birth to D&D soon spawned an entire ecosystem of derivatives, many better than the original. They often used the expedient of ‘spell points’ or ‘energy points’ to model magic use: spells cost points to cast, you had a set pool of points to spend on whatever spells you wanted to case, and when you used up your spell points you were spell-less. Spell points made good sense in terms of game mechanics, but they didn’t make sense in terms of the fantasy worlds where these games took place. What force were spell casters drawing on? The concept of mana came to the rescue.

Mana has been floating around fantasy and gaming fandoms for some time, partially because of Eliade, but also because of Larry Niven. In 1969, Larry Niven published the short story “Not Long Before The End.” The story was set in the distant past, when the environment was suffused with mana. Wizards consumed mana by casting spells, slowly using it up. The result was our current, disenchanted world. Published four years after Frank Herbert’s Dune and the same year as the Santa Barbara oil spill, some people saw in Niven’s work an ecological message about nonrenewable resources. In fact, Niven’s inspiration was a book he had read in college: Peter Worsley’s The Trumpet Shall Sound. Worsley’s book described cargo cults in New Guinea, many of which drew on Austronesian visions of the distant past as a time of powerful ancestors whose knowledge and capacities had been imperfectly handed down to us in the present. The story was superbly told, frequently anthologized, and resulted in several spin-offs. As a result, word of mana spread.

In California’s atmosphere of psychedelic medievalism, Eliade’s influence was more direct. The Bay Area was home to a variety of growing movements: the Society for Creative Anachronism, growing neo-paganism, and a lot of people who were into D&D. One of them, David Hargrave, produced a variant of Dungeons and Dragons in the mid 1970s that he published in a series of books known as the Arduin Grimoire. Hargrave built the magic system for his game with the help of Isaac Bonewits, the future Archdruid of the New Reformed Druids of North America. Bonewits shared Eliade’s love of synthesis and sense of adventure—he had a bachelor’s degree in ‘magic’ from the University of Califoria, a major of his own design Bonewits certainly read Eliade, and worked to synthesize the disparate religious systems he read about into a single system. The result, was ‘neo-paganism’ a movement that Bonewits helped found. In fact, in 1978 Bonewits produced the book “Authentic Thaumaturgy” which described how to create in-game magic systems based on how real magic worked. The Arduin Grimoire, RuneQuest, and other games drew strongly on Bonewits expertise with ‘real’ magic when they designed their ‘fantasy’ versions.

D&D’s leap from the tabletop to the computer happened almost immediately, although it took a bit longer for mana to follow it. The computer, like LSD, was created by America’s military industrial complex, only to be appropriated by the counterculture as a tool for self-expression. A lot of this appropriation took place in Silicon Valley, within driving distance of Isaac Bonewits’s coven. It was a match made in heaven: the same eggheads who played D&D and read Larry Niven also programmed computers. The speed with which people wrote D&D-inspired video games was breathtaking: Dungeons and Dragons hit shelves in January 1974. By August 1975 the first computer version appeared.

This earliest computer games inspired by Dungeons and Dragons were pretty crude—too crude, in fact, to have the complex spell mechanics of table top games. It would not be until the 1980s when computer games would have complex implementations of magic. When they did, the most influential ones used a spell point system. Ultima III appeared in 1983 and used magic points, which were abbreviated in on-screen as ‘MP.’ Final Fantasy, the famous Japanese role playing game, also adopted MP when it appeared in 1987. That same year, in the States, the highly influential video game Dungeon Master made it clear that the ‘M’ in ‘MP’ stood for mana.

The world of computing games was not immune to external influences. Mana was also making inroads elsewhere. In 1993 Richard Garfield produced Magic: The Gathering, the game the single-handedly created a whole new genre of geekdom: the trading card game. In Magic: The Gathering (M:tG as it is known) players imagined themselves as powerful wizards, battling with each other for supremacy. Two players faced off against each other, playing cards drawn from a their own custom-designed decks. Each card was (to simplify a bit) a monster or enchantment which could be used to attack the other player’s cards. Strategically, it was a blast. But the game’s added addictive twist was cards were sold in baseball card-like packs. You never knew exactly what you would find when you opened a fresh pack, and the result was a ginormous secondary market where players bartered, traded, about bought cards as part of their quest for a perfect deck.

Mana was central to M:tG: it was the magical energy that players harvested from the land (that is, small cards with pictures of land on them) and used to activate the cards in their hand. If this sounds reminiscent of Larry Niven’s “Magic Goes Away” series, it’s because it was. The game even included a magical disk that consumes all magical creatures and artifacts around it, just as Niven’s story had. It is even called “Nevinyrral’s Disk,” which betrays the disk’s origins to anyone who can read backwards.

M:tG proved immensely popular, and video game designers played it alongside everyone else. That included the people at Blizzard Entertainment. Originally located in Irvine, the people at Blizzard played M:tG to take a break from designing video games, as did their sister company, Blizzard North, which was based in the Bay Area. It was a tightly-knit world: One of Blizzard North’s artists, Michio Okamura, had previously illustrated volumes of the Arduin Grimoire.

Blizzard made history in 1994 with the release of the computer game Warcraft: Orcs & Humans. This first Warcraft—Warcraft I as they now call it—was innovative because it was a “real time strategy” or “RTS” games. Most older strategy games had basically worked like chess: you moved all your units, pressed the ‘end turn’ button, then the computer moved all its units, and so on. Warcraft took advantage of the computing power of the new PCs and ran in ‘real time’—you gave your armies orders and they carried them out right before your eyes. The game had a different rhythm than today’s jittery, gun-heavy slaughterfests, something more akin to a slow and mounting sense that things were building up than an adrenaline rush. The sense of buildup was increased by the fact that you were literally building up: In Warcraft you commanded an economy as well as an economy. You started with just a few peons and then slowly built farms, barracks, lumber mills, and castles. You had to keep the resources flowing to keep the soldiers pushing the front forward.

Spell-casting units in Warcraft used a spell point mechanic, and their magical energy was measured by a green bar. What kind of magical energy was it? No one seems to be sure. Apparently the developers had never developed a backstory for their game deeper then “orcs and humans fight.” The reasons why were made up by one employee, who made it up the backstory as he went along.

Warcraft II, released in 1995, changed all that. Now there was a guy who’s whole job was to create world for the game to take place in. In this game, mana was the official unit of magical energy and the bar that measured it had turned blue. In 1996, Blizzard North produced the first Action-RPG, Diablo. Diablo had even less backstory than Warcraft (“everyone wants to hit a zombie with a club,” opined Blizzard North founder Max Schafer, “but not everyone wants to read badly written fantasy text.”), but it did have a large blue orb that measured mana. Mana was now part of Blizzard’s lexicon.

Soon whole fantasy universes sprung up around Diablo and Warcraft. More games came out: Warcraft III and its expansion Warcraft III: The Frozen Throne. The racial confrontation of orcs versus humans mutated into a confrontation between two multi-species alliances: Horde versus Alliance. More factions joined—now you could play elves and dwarves. The cut scenes grew elaborately beautiful and featured realistic three-dimensional characters fighting in battles recorded with jerky, cinema verité camera style. When the first Infernals of the Burning Legion land on Azeroth, it looks like the event was filmed by a TV crew afraid for their lives. The stories connecting the battles became almost belle lettristic—half grudge match, half soap opera, as the plots and character from games written years apart turned into a world, a legend, an ethos. By the time that World of Warcraft launched in 2004—on the tenth anniversary of the release of Warcraft I—Warcraft had become an elaborate mythic world the size of the Iliad and a profitable franchise rivaling McDonalds. Mana was an inseparable part of it.

For Pacific Islanders, the history of mana is important because it is about them: their lives and their heritage. To video game players it is important, and for pretty much the same reasons. Once an import, mana has now become part of our culture. Some might be tempted to read the story of mana as a tale of cultural appropriation in which Westerners ransack the culture of the colonized. They may be right. Missionaries, anthropologists, and historians put mana between the pages of their books and stored it in libraries all over the world. But gamers did something else with it: They cared for it. They made fantasy games and imaginary worlds, and came to love what they had created. They put mana into play, making it part of their lives, dragging it into their histories and self-understandings. They spent hours optimizing their healing spells and living the lives of draenei shamans. Gaming became part of who they were, and mana became part of their heritage. Did they borrow it? Yes. Did they exoticize it? Perhaps. But by playing with it, they honored it. The world is full of stories like the story of mana, stories whose paths across cultures and through time are rarely fully recorded. But these stories matter to us, because their histories are part of our lives. Like mana, they lay in the background until—click—someone shines a light on them and we see the power they truly possess.

Many people helped with this article. I’d like to thank Jon Peterson, my coauthor on the academic version of this paper, for his scrupulous reading of this paper. I’d also like to thanks Steve Perrin and Larry Niven for answering my questions about their work and career. Professor Robert Blust, the Reverend Terry Brown, and Michael Craddock reviewed the manuscript to make sure I got all my facts straight. Any errors are my own.