Where Be Monsters? The Daedalus Sea Serpent and the War for Credibility

On 6 August 1848, Midshipman Sartoris of the Royal Navy corvette HMS Daedalus alerted the officers on the ship’s quarterdeck to an unusual sight. The captain, first lieutenant, and sailing master were all present to see the approach of a large creature of a kind none had observed before. Captain Peter M’Quhae, in command of the vessel, described the encounter in his official report to the Admiralty:

It was discovered to be an enormous serpent, with head and shoulders kept about four feet constantly above the surface of the sea; and as nearly as we could approximate by comparing it with the length of what our maintopsail-yard would show in the water, there was at the very least sixty feet of the animal a fleur d’eau no portion of which was, to our perception, used in propelling it through the water, either by vertical or horizontal undulation. It passed rapidly, but so close under our lee quarter that had it been a man of my acquaintance I should have easily recognised the features with the naked eye.

It’s unfortunately typical of the sea serpent’s treatment over the years that my first response on reading this was to write a novel about what might have happened next.

Perhaps I should have started by looking further into what actually happened, which initiated a debate that remains unresolved. The fictional crew of my Daedalus risk life and limb fighting a very real creature. The real crew of the Daedalus risked reputation and career by telling the world about something that perhaps some people weren’t ready to hear.

An article about the sighting written a few years afterwards stated confidently “that there is such a creature, however, there can be little doubt, as his appearance has been so often alluded to.” And that sighting, 165 years later, remains one of the best pieces of evidence for the existence of the giant sea serpent—a creature that has captured imaginations for centuries, yet remains elusive.

The Daedalus sea serpent neatly encapsulates the discourse around this mysterious creature: a mixture of public fascination and scientific dismissal. Almost from the instant the Daedalus returned to England, the crew’s claims generated both childlike enthusiasm and determined rejection. The first public report of the sea serpent was in the Times of 10 October, six days after the corvette’s return. The same newspaper later published comments by the biologist Sir Richard Owen, who claimed that the most likely explanation for the sighting was that it was an elephant seal swimming in open water. Owen suggested that what the officers had thought to be the creature’s tail was the long eddy that typically trailed behind an elephant seal.

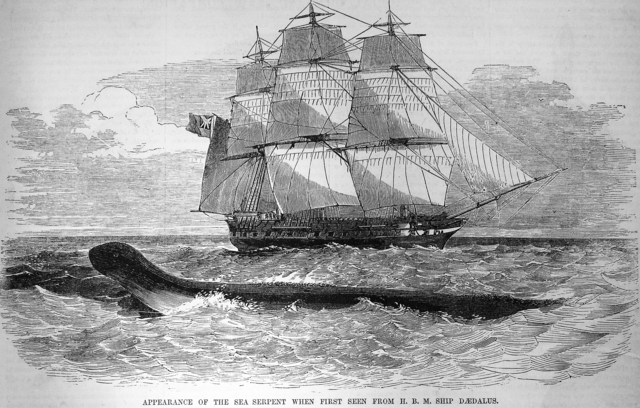

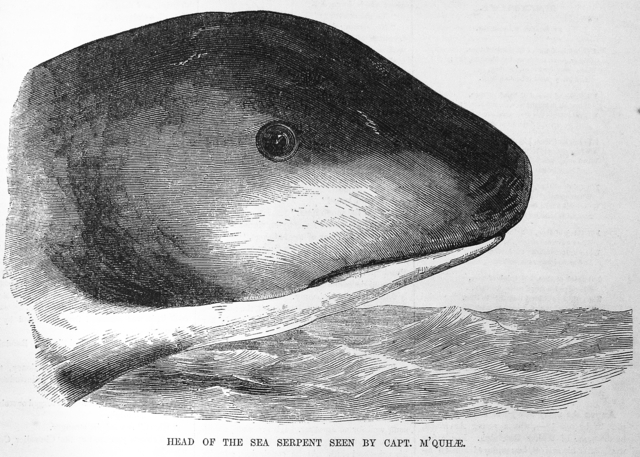

Captain M’Quhae angrily rejected Owen’s claims, but the story was already causing a certain amount of embarrassment to the Admiralty. Questions arose in Parliament about how a Royal Navy captain could have allowed the report to be printed. Undeterred, M’Quhae collaborated with an illustrator to produce a series of engravings of the encounter, and these appeared alongside a copy of M’Quhae’s report to the Admiralty in the Illustrated London News.

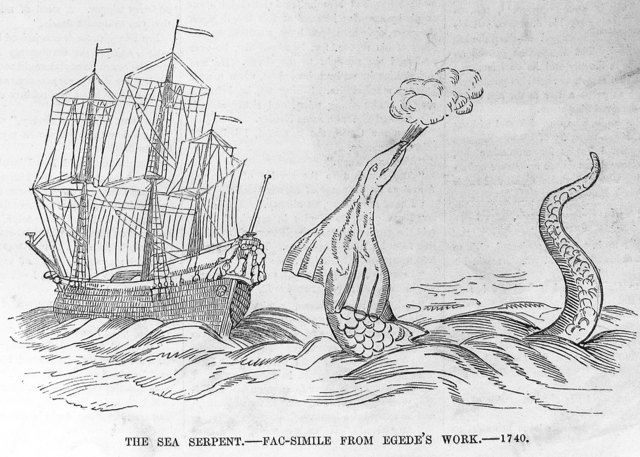

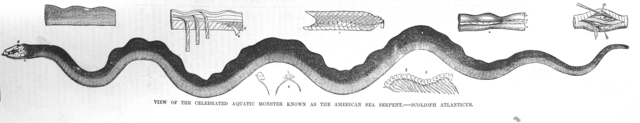

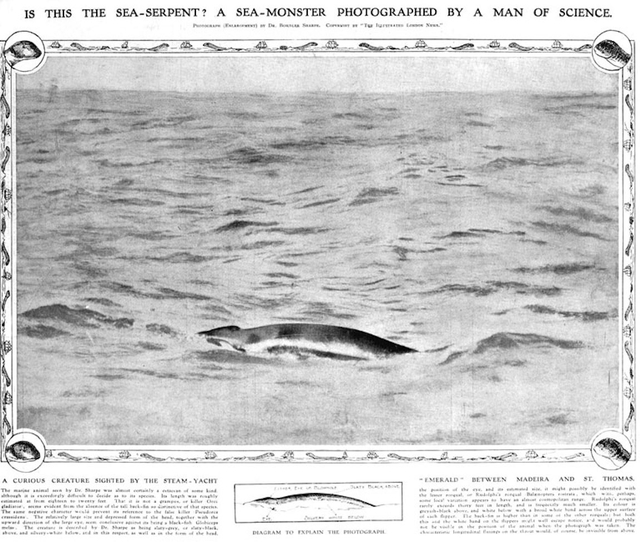

In addition to three images portraying the Daedalus sea-serpent, the paper reproduced an anatomical drawing of the “American Sea Serpent, Scolioph Atlanticus” and an illustration representing a 1740 sighting off Norway.

Undoubtedly, much of the interest in the Daedalus sea serpent over the years has stemmed from those illustrations, which turned M’Quhae’s rather clipped description into a living, breathing scene. Yet the characters of the witnesses from whose accounts the illustrations had been drawn were equally important. In an era with no photographs, these drawings were as good as it got: professionally-drawn illustrations based on the first-hand accounts of men whose reputations were close to unimpeachable.

The reliability of the witnesses was key. Royal Navy officers were expected to be steady, precise, and not prone to flights of fancy. Furthermore, in the mid-nineteenth century, the Royal Navy’s officer corps was an increasingly scientific body. The developments in meteorology, weaponry, navigation and propulsion in the first half of the nineteenth century meant that all Royal Navy officers had to have an understanding of scientific principles, and a far more scientific outlook than their forebears.

Moreover, the Royal Navy was beginning to take more of an interest in exploration and discovery as the long Pax Britannica set in following a century of wars. This can be seen through the naval expeditions to the polar territories of Ross, Parry and Franklin (which you can read about in a previous Appendix article by Douglas Hunter), and no less importantly in the myriad surveying voyages such as those of HMS Beagle.

These developments reflected changes in British society. The British gentleman was an increasingly scientific creature. Moreover, science itself was developing into the more specialised field we know today. When the British Association for the Advancement of Science had been founded in 1831, its committee had selected a relatively narrow set of disciplines and rejected fields such as agriculture and music, despite determined lobbying.

It’s hard to imagine that men such as the officers of the Daedalus would have opened themselves up to the risk of career damage and social ridicule lightly. Indeed, they had every right to expect that their account would be evaluated methodically. Observation and recording of natural phenomena by ‘reliable witnesses’ was an important part of science in the early nineteenth century. Empiricism, in the true sense of the word—knowledge based on the evidence of your own eyes—was the essence of nineteenth-century naturalism, which at the time referred to all study of the natural environment including astronomy and geology.

In this light, the immediate attempts in some quarters to dismiss the sighting are surprising. The biologist Richard Owen, for example, seems to have reached for ‘rational’ explanations without considering for a moment that the sighting was indeed of a giant sea serpent. Owen, who coined the term ‘dinosaur,’ was no stranger to fantastic creatures. His suggestion that professional sailors who had spent a career at sea (M’Quhae became a lieutenant during the Napoleonic wars) might not have seen an elephant seal before is not entirely credible. His immediate leap to find alternative explanations is indicative of an attitude that was already becoming entrenched: sea serpents were not to be taken seriously by scientists.

There had been no shortage of reported sightings of sea serpents over the previous two centuries.

In the port of Gloucester, Massachusetts, a sea serpent was reported in the bay with startling frequency from the mid-seventeenth century, culminating in eighteen sightings in the year 1817 alone. The twelve months following the Daedalus sighting produced two potential confirmations. Later in 1848, an American brig reported a similar creature in almost exactly the same place (between St. Helena and the Cape of Good Hope), and the following year a Royal Navy sloop made another strikingly similar sighting in the North Atlantic.

Yet the nineteenth-century scientific elite were not exactly open-minded about the existence of such creatures.

There are many reasons why this may be. Both errors and hoaxes had produced so-called proof of the existence of sea serpents in the recent past, which had swiftly been debunked. “Sea serpent fever” in New England generated by the numerous Gloucester sightings proffered one example. In fact, the very anatomical drawing of “Scolioph Atlanticus” attached to the Daedalus story originated in a bizarre mistake by a member of the New England Linnaean Society in 1817. The over-enthusiastic discoverer had found a deformed terrestrial snake on a beach, and took it to be the juvenile form of the sea serpent that had been causing a stir out in the bay. The error was quickly discovered, but apparently persisted thirty years later. The association of the Daedalus sea serpent with a well-known error can have done little to help its credibility in scientific circles.

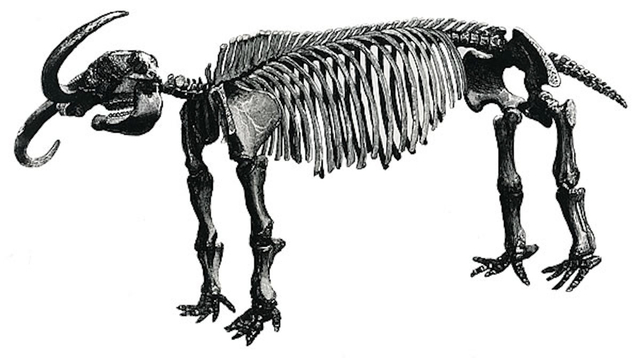

Koch’s ‘Missourium’ skeleton, fraudulently cobbled together from multiple mastodons. Wikimedia Commons

This wasn’t the only event that heightened professional skepticism around sea serpents even as it fed public enthusiasm for the creatures. Just three years before the Daedalus sighting, celebrated fraudster ‘Dr.’ Albert Koch unleashed his latest piece of paleontological trickery on a credulous public. Koch had earlier jumped on the bandwagon created by the discovery and display of fossil skeletons by respectable naturalists and developed it into his own brand of Barnum-esque showmanship. Koch’s ‘Missourium’ skeleton, which he even managed to sell to the British Museum, was a fake cobbled together from several mastodon skeletons with additional blocks of wood to make it bigger, with the tusks pointing outwards (possibly to make it look fiercer, or just different from the existing mastodon skeletons on display).

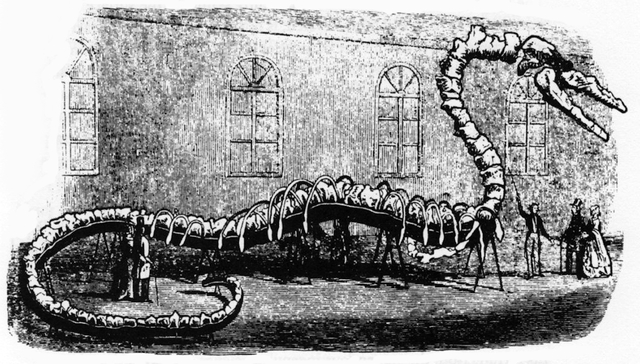

With ‘Missourium’ successfully disposed of, Koch turned to the fashionable sea serpent for his next showpiece. The prehistoric whale Basilosaurus had been discovered in 1835, but as with the mastodon, Koch endeavored to go one better. In the first four months of 1845, Koch traveled across three counties known to contain Basilosaurus remains and assembled parts of at least six skeletons as well as pieces of other whale skeletons and even Ammonite shells. The result was the 114-foot “Hydrarchos – or Leviathan of the Antediluvian World, As described in the Book of Job, Chapt. 41,” according to Koch’s promotional material.

Koch’s frauds had been immediately pointed out by naturalists including Owen, who had in fact been instrumental in the identification of Basilosaurus as a mammal, not a lizard as originally thought. This simply created greater publicity for Koch and increased the number of visitors. Koch sold the ‘Hydrarchos’ and promptly made a second one.

It was perhaps due to foolish errors like ‘Scolioph Atlanticus,’ as well as outright scams like ‘Hydrarchos,’ that claiming any association with a sea serpent could lead to widespread ridicule. By 1848, the sea serpent had already fallen into the domain of the pseudo-scientific. In another century, the giant sea serpent would become the poster-child for the new pseudo-science of cryptozoology, but this process had begun much earlier. The barrage of sea-serpent sightings was, in the mid-nineteenth century, already being met with a number of ‘explanations’—some of which were themselves seem to us more implausible than the idea of the sea serpent.

The desire to explain the Daedalus sea serpent as anything but a sea serpent didn’t go away. A decade after the incident, Captain Smith, of the Pekin, sighted a sea-serpent while the ship was becalmed near the Cape of Good Hope. It turned out to be a twenty-foot piece of floating seaweed “with a root shaped like a head and neck.” Smith had little hesitation in declaring that the Daedalus sea serpent (encountered not too far away, off St. Helena) must have been “a piece of the same weed.” The explanation was again swiftly denied in a letter in the Times of 13 February 1858. The author of the letter insisted that the sea serpent was “beyond all question a living creature, moving rapidly through the water in a cross sea, and within five points of a fresh breeze, with such velocity that the water was surging under its chest as it passed along at a rate, probably, of not less than 10 miles per hour.” Interestingly, the letter was signed simply as “An Officer of Her Majesty’s Ship Daedalus.” Each of the officers who had seen the sea serpent had been named in the contemporary reports, so it is tempting to conclude that anonymity was now adopted for reasons of reputation.

The entry on sea serpents from the 1902 Encyclopaedia Britannica lists a string of “likely” phenomena mistaken for sea serpents. These include: A school of porpoises; a flight of sea-fowl; a large mass of seaweed; a pair of basking sharks; ribbonfish/oarfish; giant squid; a whale, and a sea-lion. The encyclopaedia concludes that “with very few exceptions, all the so-called ‘sea serpents’ can be explained by reference to some well-known animal or other natural object.”

Many of the ‘rational’ explanations subsequently offered rely on substantial mistakes in interpretation, over-excitement, or difficulties with observation such as distance or poor light. It is hard to see how, assuming the phenomenon sighted behaved as the Daedalus’s officers described, it could possibly have been a piece of seaweed, or indeed a whale or elephant seal.

Whatever the reality, the number of reported sea serpent sightings declined rapidly after the nineteenth century. Writing in 1925, Austin Clark of the Smithsonian Institution offered a typical explanation for the decline. “In the last 20 years,” Clark noted, the size of ships rapidly increased and steam ships replaced sailing vessels. These maritime advances mean that the “vantage point” for observing the sea serpent moved “from the low and insecure wave-washed deck of a small sailing boat to the high, comfortable, secure, and relatively dry deck of a much larger steamer.” This shift in perspective “removed the element of fear and hence dulled the imagination so that sailors are now able to study calmly and report correctly what they see.”

The officers of the Daedalus may have had something to say at the suggestion that their sighting could be put down to a permanent state of fear generated by their “wave-washed … small sailing boat.” (In reality, it was a 1,000-ton, 150ft ocean-going vessel.) Furthermore, sea serpent sightings did not stop when large steamships became the norm. Captain Sir Arthur Henry Rostron, who was later responsible for the rescue of the Titanic survivors, reported seeing a sea serpent on April 26, 1907, while acting as Chief Officer of the RMS Campania. Nevertheless, the notion that the sea serpent sighting is an essentially age of sail phenomenon is intriguing.

Indeed, it is often assumed that reports of sea serpents originate due to poor conditions for observation—great distance, poor light or bad weather, for example. Yet this was not always the case. A meeting of the Zoological Society of London on the theme “Cryptozoology: Science or Pseudoscience” in July 2011 discussed the large number of sea serpent sightings made in good conditions for observation, such as that of the Daedalus. As palaeozoologist Dr. Darren Naish of the University of Southampton observed:

People that work on this area (most notable among them the ichthyologist Charles Paxton) argue that, while many accounts can be re-interpreted as sightings of known animals, there is still a hard-core of decent sightings, often reported by experienced, qualified observers, which describe animals as yet unknown.

Naish professed his frustration “that many people seem to find it utterly inconceivable that one can be interested in cryptozoology (perhaps even interested enough to publish on the subject). Yet they remain strongly skeptical of eyewitness testimony in general, of the existence of alleged cryptids, and of the claims made in the cryptozoological literature.”

Attitudes to cryptozoology may be changing. A 2009, a study sought to assess how many large species of marine creature might still await discovery. Interestingly, the study took the approach of combining statistical methods with a study of so-called ‘grey literature’—pseudo-scientific sources not recognized by the scientific establishment.

“Because cryptozoological data are mostly discussed in the ‘grey literature,’” the authors observed, “appraisals of these cryptids have never appeared in the mainstream literature, perpetuating a cycle whereby these putative animals remain unevaluated.”

In other words, the giant sea serpent has passed from pre-modern ‘here-be-monsters’ speculation into the contemporary equivalent of Fortean conspiracy theories without any real scientific evaluation. For all the thousands of reported sightings throughout the centuries, no firm evidence to prove or disprove the existence of such a creature as that reported by the Daedalus has ever been produced. Perhaps the time will come when the officers of the Daedalus will finally be vindicated. At the very least, we should take them seriously as historical actors. Did the officers suffer any harm to their careers or their social lives as a result of their honesty? Did the Admiralty discourage further reports for fear of further ridicule in parliament? What was it that made the scientists so quick to ignore the witnesses’ reports?

Above all though, the abiding question is the same as it has always been. Just what was it that they saw?