Hunting Gorillas in the Land of Cannibals: Making Victorian Field Knowledge in Western Equatorial Africa

With a groan that had something terribly human in it and yet was full of brutishness, he fell forward on his face. The body shook convulsively for a few minutes, the limbs moved about in a struggling way, and then all was quiet—death had done its work, and I had leisure to examine the huge body.

—Paul Du Chaillu on killing a male gorilla, Explorations and Adventures in Equatorial Africa, 1861

By most accounts, Paul Belloni Du Chaillu made an exemplary African field collector. Born on the island of Reunion in 1831 to a French trader and a mother of (potentially African) unknown origins, the swarthy boy demonstrated a remarkable knack for languages at an early age. Alternating between his studies at an American Protestant mission school on the coast of Gabon and working for his father’s trading company, Paul Du Chaillu somehow found time to train in hunting Africa’s Beast Among Beasts (now known as the Western lowland gorilla) under John Wilson—the coastal collector supposedly responsible for felling Britain’s first gorilla in the late-1830s.

Realizing that his education could only take him so far in Gabon, Du Chaillu left to explore his first terra incognita—Philadelphia. Within a matter of months, the young explorer had made a name for himself in the American natural history lecture circuit, thrilling wealthy patrons with his stories about sweltering African jungles and their animal inhabitants.

Before long, Du Chaillu grew weary of his role as lecturer and entertainer, yearning for scientific credibility and, certainly, the funding that came along with professional status. By a series of lucky connections and a web of supportive associations, the collector’s stories made their way into the most important conversations about the Dark Continent, circulating in Britain’s Royal Geographical Society (RGS). While admittance to the increasingly professionalized RGS required backing from a contemporary fellow, some particularly worthy field collectors won membership simply because of their contributions to controversial and exciting fields.

By midcentury, Victorian natural historians—and the rising middle-class reading public—seemed hungry for information from formerly inaccessible regions of Africa, occasionally bending scientific standards like established sponsorship for stories on things like apes, cannibalism, fetishism, and deviant sexuality. This slight slip in RGS standards provided Du Chaillu with a valuable opportunity. The explorer’s language acumen, “tolerably thorough acclimation,” and connections to Gabonese coastal traders promised to serve him well among the fascinating “tribes of the interior.” If he could collect new animal specimens, observe scintillating African behaviors, and cover fresh territory in the interior, Du Chaillu stood a good change of leaving his status as “field collector” behind and making his way into a royal society.

A number of excellent histories have been written about Paul Du Chaillu and his role in the Royal Zoological Society’s “Gorilla Wars” of 1861. Because of his apparent racial ambiguity, prolific (and entertaining) writing, and general habit of stirring up professional controversy, Du Chaillu has received his fair share of published coverage. Missing from these histories, however, is Du Chaillu’s intense reliance on his “tribes of the interior” in producing what came to be seen as ‘Western’ scientific knowledge. Gabon’s interior became a site where an explorer could negotiate his social and scientific position using African interpretations of moments of scientific ambiguity.

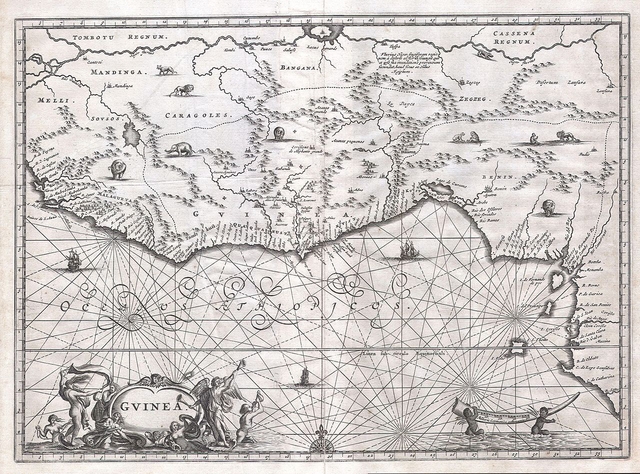

This 17th century map of West Africa reveals the European ignorance of the areas interior regions. Wikimedia Commons

Victorian stories about black bodies, gorilla bodies, and cannibalized bodies tend to be read as merely racist products of anthropological ignorance. Moving beyond this, though, we can attempt to read through these Western texts to understand how Western Equatorial Africans themselves understood the political, social, and environmental unrest surrounding them. Du Chaillu, like most other explorers, entered a pre-existing network of knowledge and exchange. In his efforts to paint himself as a quintessential white, professional, Victorian explorer, Du Chaillu in fact positioned himself within a far more complex system of African storytelling, and storytelling in general.

Narratives about the field collector and his duties, widely discussed in both scientific societies and in the Victorian popular press, circled around an inherent sense of physicality. These men (for they were almost exclusively men) survived extreme climates, trekked across treacherous landscapes, felled dangerous animals, and found themselves in the constant company of “savages”—all in the name of advancing scientific knowledge. As colonial expeditions opened up new inroads into Western Equatorial Africa, ethnographic accounts moved from relative scientific obscurity to sensationalized fascination, nervously read by Victorian elites. The accounts that generated the most press, and oftentimes the most money, hinted at the fogginess in classifying animals as separate from humans, at the temptations towards savagery rampant in the Dark Continent’s jungles, at what all of this might mean for readers in their drawing rooms back home.

Successful field collectors and their invisible African counterparts exhibited, above all else, physical strength, hunting acumen, and a discerning eye for useful observation. Paradoxically, many of these same traits supposedly characterized the indigenous Fang communities living in Gabon’s interior, employed by Du Chaillu as porters, hunters, and informers. Fang men were, until very recently, presented in ethnographic accounts as possessing heightened masculinity and as fierce warriors—their sharpened teeth no doubt colored impressions of Rousseau-inspired savagery.

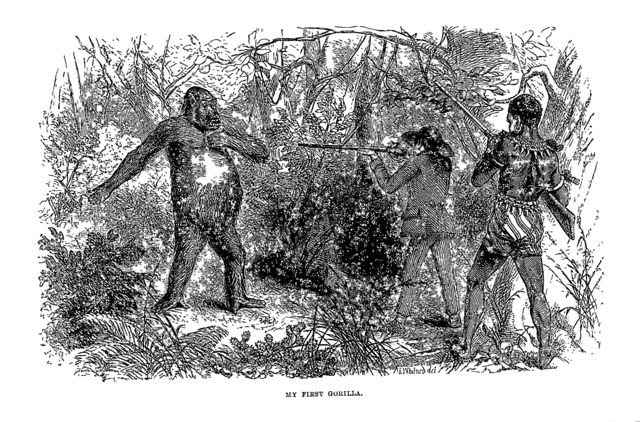

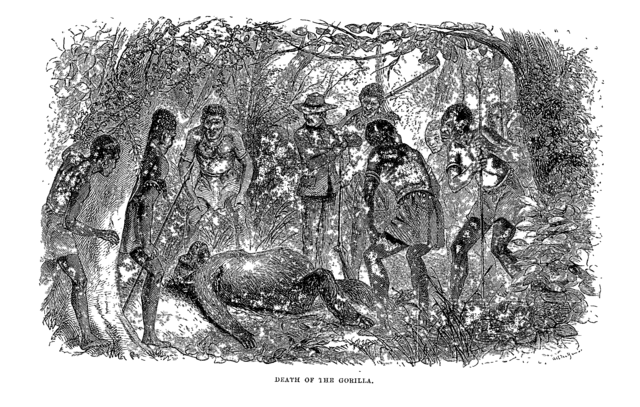

Despite his desire for professional scientific credibility, Du Chaillu’s strengths lay in the very traits required of field collectors. He was known, within the royal societies, as a gorilla hunter. Well-familiar with the demand for gorilla specimens by the Royal Zoological Society and the British Museum, the young explorer recounted an almost unbelievable number of close encounters with the apes. In describing these graphic, disturbing hunts, Du Chaillu placed less emphasis on his examination of the “huge bodies” of gorillas so desired by natural historians, and far more on the image of the live gorilla, on his own hunting prowess, and on the beast’s slow and painful death. Surrounded by his Fang hunting companions, the explorer tracked down “an immense male gorilla,” writing that:

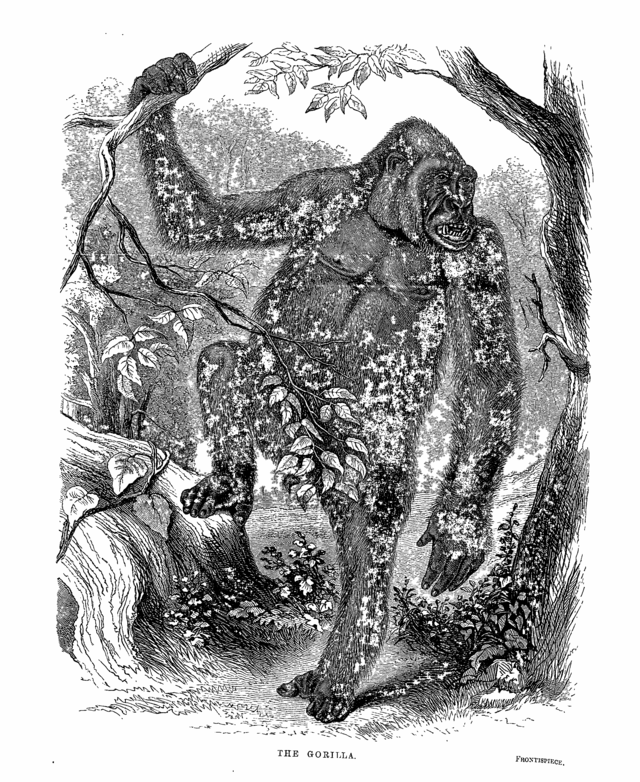

When he saw our party he erected himself and looked us boldly in the face […] Nearly six feet high, with immense body, huge chest, and great muscular arms, with fiercely-glaring large deep gray eyes, and a hellish expression of face, which seemed to me like some nightmare vision: thus stood before us the king of the African forest.

A male gorilla, featured as the frontispiece to Du Chaillu’s tome. Du Chaillu, Explorations and Adventures

The societies funding his expedition needed, above all else, gorilla skeletons to study and display back in Britain. Preserving specimens in the tropics and keeping them safe on months-long journeys across the ocean, however, proved difficult. One gorilla specimen made it back to the British Museum, but zoologists generally had to make due with illustrations and textual descriptions of gorilla behaviors. What they got from Du Chaillu, though, was probably a series of sensationalist hunting stories. This, then, forced RGS fellows to question whether the young explorer truly was describing real gorilla encounters, or whether he was playing into popular, sensationalist desires for drama and death.

Time and time again, Du Chaillu claimed that he, alone, was responsible for the kills. This might not seem remarkable on the surface, because it fulfilled such typical hunting tropes. However, Du Chaillu’s singular obsession with his kills stands out when his fixation with the physicality of field work is compared with works about gorilla encounters by other explorers attempting to recreate his expedition.

Respected explorer Richard Francis Burton embarked for Gabon only a few years after Du Chaillu returned. In contrast to De Chaillu’s emphasis on prowess, Burton claimed that in hunting, “everything depends upon ‘luck.’” He went on to admit that he “utterly failed in shooting a gorilla,” and even that “the Gorilla is a poor devil ape, […] not the king of the African forest.” Returning to these same Gabonese forests later in the century, anthropologist and adventuress Mary Henrietta Kingsley characterized a family of gorillas as “ladies” and a “young gentleman,” uttering “a quaint sound between a bark and a howl.”

Du Chaillu’s stories about the king of the jungle certainly sold a number of books to intrigued and horrified upper- and middle-class Victorian readers. However, the stories’ sensationalism—published largely in popular culture magazine The Athenaeum, and later in a series of children’s books—failed to convince professional natural historians of any semblance of geographic or zoological accuracy. In grappling for proof of his success as a credible field collector, Du Chaillu undermined his professional opportunities.

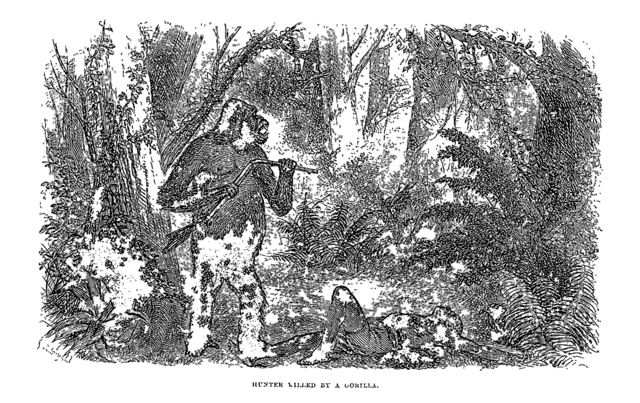

If Du Chaillu didn’t, in fact, directly participate in so many successful and dramatic gorilla hunts, as I suggest, then he had to get his ideas about the savage apes elsewhere. Despite scientific society’s calls for an African specimen collection and anthropological observation, few explorers had actually made it into Gabon’s interior before Du Chaillu’s expedition. Once in Gabon’s overwhelming forests, comparing plant and animal species to field guides would have been next to impossible. Fang informants guided Western explorers to known gorilla nests and passed on successful tracking and hunting methods. In all likelihood, Fang communities informed more than just field knowledge—their stories about gorillas and cannibalism eventually made their way into Western ‘scientific’ writing. Certainly, Du Chaillu’s more sensationalist passages about gorilla kidnapping, rape, and torture played into Victorian readers’ thirst for shocking evidence of assimilation and simiation.

Curiously, the passages also reflected Fang anxieties about colonialism, trade, and environmental change. In Du Chaillu’s words, “one of the [Fang] men told a story” about a Mbondemo woman raped by a male gorilla, and “one of the men told how” a gorilla attacked and tore the fingernails off of sugarcane workers. “Finally,” he wrote, “came the story that is current among all the tribes who are acquainted with the habits of the gorilla”—the beast waited for passersby and then silently choked them. Rather than reading these stories as mere “fantasies of racist outsiders” designed to sell books, we can study Western incorporations of African stories to reveal more complex Fang speculations predating the arrival of explorers. Fear of gorillas’ physical similarity to men ran rampant in Fang as well as Victorian society. For the people who encountered the beasts regularly, gorilla stories pointed to the blurriness of the human/animal boundary, and stood in as metaphors for unexplainable atrocities.

Perhaps the most unexplainable atrocity of all existed in stories of human cannibalism. Du Chaillu relied exclusively on the Fang in describing his ‘observations’ of cannibalism among people of the interior. Western texts have recycled the cannibalism theme in countless contexts and narratives, particularly during the period of colonial expansion. It is, of course, easy to see how cannibalism may have been used as a narrative device intended to shock readers and to represent an utter lack of morals in supposedly uncivilized peoples. But stories of cannibalism also circulated among Western Equatorial Africans both as representations of loss of bodily control and as a scare tactic designed to confine trade to one’s own community.

In her extensive study of Gabonese storytelling during colonialism, historian Florence Bernault pushes these analyses further, claiming that reports of cannibalism functioned as a “hidden conversation across the racial line, and in tangible battles where Europeans controlled black bodies while Africans attacked, stole, and recycles white ones.” Fang stories of cannibalism crossed spiritual and physical boundaries and were often represented in fetish worship, expressing fears about social reproduction. Despite the fact that cannibalism did not, in fact, occur in Western Equatorial Africa, stories circulated throughout most West African societies, in white settlements along the coast, and in sensationalist and scientific texts back in Britain.

Most incredibly, Du Chaillu claimed that he directly observed instances of cannibalism among the Fang. Upon arriving at a village in the interior, he wrote:

I perceived some bloody remains which looked to me to be human; but I passed on, still incredulous. Presently we passed a woman who solved all doubts. She bore with her a piece of thigh of a human body, just as we should go to market and carry thence a roast or a steak.

The encounter is a curious one. Clearly, Du Chaillu expected to observe cannibalism upon arriving in Fang land based on stories told by other Western Equatorial Africans and on Victorian fears about these relatively unknown people. Nevertheless, he claimed that his direct visual experience “solved all doubt” raised by circulating stories. It is possible that these ludicrous passages truly were products of an editor’s creative work. In any case, Du Chaillu’s apparent ‘field knowledge’ existed within frameworks of what Victorian readers expected when buying an African travel account, and what Western Equatorial Africans talked about in the interior. Whether or not he actually believed that he saw a Fang woman carrying a human thigh off for consumption, his story provided such a striking image that other explorers traveled to Gabon over the next few decades to disprove the myth.

Fang stories about the environment, fetishism, and colonialism still receive little treatment in colonial historiography. Because these stories were largely oral, historians have little evidence to go on beyond Western field accounts. These field accounts, which were ultimately incorporated into scientific texts back in the royal societies, were produced in an ambiguous grey area between Fang storytelling and Western expectations. The explorer was required to report on in-demand subjects by financers at the royal societies, was promised fame and fortune by educated Victorian readers of sensationalist travel stories, and worked in the field alongside (and often at the mercy of) Fang informants, hunters, and traders.

Stories of gorillas and cannibalism, like stories of fetishism and sexuality, were socially charged across both continents. Boundaries blurred in African storytelling, field notes, popular travel accounts, and authoritative scientific writing. Gorilla specimens themselves became secondary to sensationalist, controversial hunting stories. Stories about cannibalism yielded very real consequences on black bodies, supporting colonial civilizing missions in the interior.

Paul Du Chaillu never achieved the professional scientific credibility that inspired his expeditions. After struggling to make his way into the Royal Geographical Society for the next decade, the explorer embraced his role as collector and entertainer, publishing a number of popular travel books and eventually dying on a trip to Russia in 1903. In the wake of his death, fact and fiction continued to overlap as Carl Akeley embarked on gorilla expeditions to Western Equatorial Africa, and a pulp novel titled Tarzan of the Apes, a novel based on Du Chaillu’s stories, captivated the imagination of young readers.