The Aviator’s Heart

Amidst hangars full of airplanes and aviation memorabilia, visitors to Brazil’s National Air and Space Museum encounter a much stranger object. It is a gold plated celestial globe, supported by a marble statue of an Icarus-like figure with its arms raised skyward. There is a human heart inside the globe, preserved in formaldehyde. The heart of a man called Alberto Santos-Dumont. Brazilians consider him to be the true inventor of the airplane.

The heart of the aviator is a relic from a time when personal flying machines roamed the streets of Paris, and people were afraid that marauding anarchist Zeppelins might destroy their cities. It was the turn of the twentieth century, a golden age for inventors and tinkerers.

Flying today means frustration at airline counters, waiting in long lines to be patted down, bad food and expensive drinks. But in the first decade of the twentieth century, aviation evoked a radical new world. Some even argued that humans would physically evolve by being airborne. They imagined a future where everyone might own a flying machine. Aeronauts were great celebrities, much like astronauts during the space race. And perhaps no one was a bigger celebrity than Alberto Santos-Dumont—who used to fly his personal airship over the streets of Paris, sometimes just to go to lunch. To understand why his heart is now in a museum, we must first understand his life, and his world.

A Flying Brazilian in Belle Époque Paris

Santos-Dumont lived in Paris, where he settled in 1897 and began his aeronautical experiments. As a child, growing up in a São Paulo coffee plantation reading Jules Verne, he launched small balloons and built a small rubber band powered airplane—it seems that toy airplanes predate the real thing. Santos-Dumont’s passion for the air was sealed at the age of fifteen, in 1888, when he first witnessed a manned balloon and parachute demonstration in São Paulo.

When he moved to Paris for his engineering education, he was set on the idea of flying in a balloon. Paris was, after all, the global center for ballooning. After many rejections, he found two Parisian balloonists willing to help him build a craft. Santos-Dumont named it Brasil. He once even took off with a friend, packing a picnic of cheeses, fruit, hardboiled eggs, roast beef, chicken, ice cream and cake. And, naturally, champagne—which they found to be extra bubbly due to the low pressure at their altitude.

Soon he began experimenting with the internal combustion engines of the cars that were just starting to emerge on the streets of Paris. With these new engines, he started creating dirigibles, much like blimps or zeppelins, essentially maneuverable (cigar-shaped) balloons with engines and rudders.

Despite the dangers of mixing rudimentary combustion engines that generated sparks and a balloon envelope full of flammable hydrogen, Santos-Dumont kept on tweaking his methods and creating new dirigibles, naming each new and improved airship with a number (No. 1, No. 2, No. 3). While they had already been tested as a concept, he was the only person in the world flying a dirigible airship at the close of the nineteenth century.

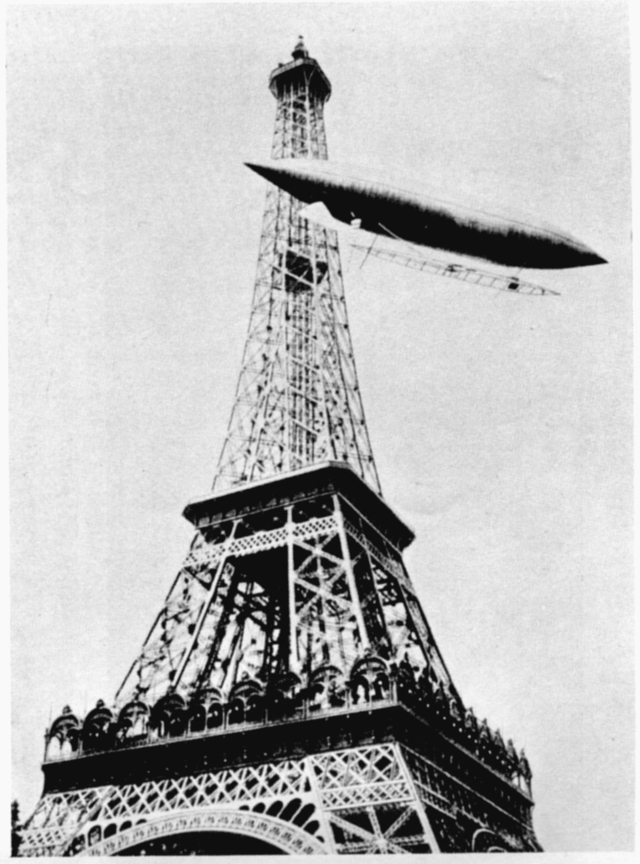

In April 1900, Henri Deutsch de la Meurthe, a French petroleum magnate and member of the French Aero Club, created a prize to foment the development of aviation. The prize was to be administered by the French Aero Club and fifty thousand francs were to be given to the first aeronaut to fly a specified trajectory around the Eiffel Tower in less than thirty minutes. On October 19, 1901, Santos-Dumont won the French Aero Club’s Deutsch Prize, rounding the Eiffel Tower and landing at Parc Saint Cloud in twenty-nine minutes and thirty seconds:

The air-ship, carried by the great impetus of its great speed, passed on, as a race-horse passes the winning post, as a sailing-yacht passes the winning-line, as a road-racing automobile continues flying past the judges who have snapped its time. […] I then turned and drove myself back to the aërodrome. […] I did not know my exact time. I cried: “Have I won?” And the crowd of spectators cried back to me: “Yes!”

He was greeted by a jubilant crowd. But the other Aero Club judges squabbled over the particulars of the timing rules, and his prize was not declared official. While the Aero Club members deliberated, Santos-Dumont did not fail to deliver in his showmanship—he declared publicly that he would give away the entire prize money—part of it to his staff and assistants, and the rest for the aid of the poorest Parisians.

The Parisian press and public pressured the Aero Club, and soon the prize was made official. Santos-Dumont’s donation of the prize made him even more popular. The aviator’s flights attracted enormous crowds. Journalists flocked from all over Europe and the United States to interview him. The New York Herald sent a journalist to Paris exclusively to cover the airship flights. Other famous contemporary inventors, like Thomas Edison and Samuel Langley, commended his triumph. They were not alone—in a visit to the United States, he was even invited to eat at the White House, where Theodore Roosevelt asked him about taking his son aboard an airship.

His celebrity as the best known aeronaut in Europe, and perhaps the world, was sealed. Santos-Dumont was as close as one could get to a rock star in Paris.

Imagine the frenetic pace of life in belle époque Paris. Automobiles appearing on the streets, attracting huge crowds. The telegraph bringing news from all over the world. Cafés playing phonographs while their patrons drank absinthe and cocaine wine. Now imagine a Parisian walking the streets in the early morning, in a time where an automobile was still a fascinating novelty, and then suddenly, a small airship appears floating just above the street. A crowd would gather to see the aviator driving his Baladeuse (The Wanderer), a personal sized dirigible, over the streets as if it were a carriage or automobile. Santos-Dumont would then land in front of his favorite café, tie the guide rope much like one might tie a horse to a hitching post, and walk in for a meal. It must have been quite a sight. Going to the café was not the only time Santos-Dumont used his Baladeuse—he was also fond of surprising his friends by landing in front of their porches with his airship.

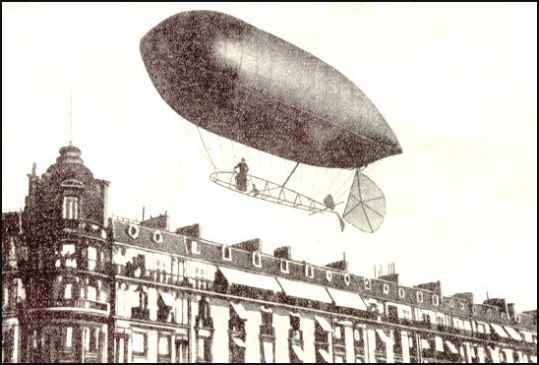

The Baladeuse (Wanderer), Dumont’s personal airship which he often flew around the streets of Paris. Wikimedia Commons

His fame even fed consumerist impulses. His countenance appeared on cigar boxes and dinner plates. Toy replicas of his airships moved off the shelves at a brisk pace. Even bakers joined in, selling airship-shaped cakes with the colors of the Brazilian flag. Fashionable boutiques sold clothing and accessories inspired by his meticulous and impeccable style. Louis Cartier, a friend of his, even made a special wristwatch to use during flight, so he would not have to pull out his pocket watch while handling the controls. In fact, Santos-Dumont was responsible for making the wristwatch a fashionable accessory among men—it was mostly a women’s item until that point.

There were compositions, poems, odes and speeches galore in his honor. Henri Deutsch de la Meurthe composed a waltz in honor of Santos-Dumont, simply titled “Santos.” The chairman of the United Kingdom Aero Club, Major-General Lord Dundonald, perhaps best expressed Santos-Dumont’s popularity in a banquet given in his honor in London:

“When the names of those who have occupied outstanding positions in the world have been forgotten, there will be a name which will remain in our memory, that of Santos-Dumont.”

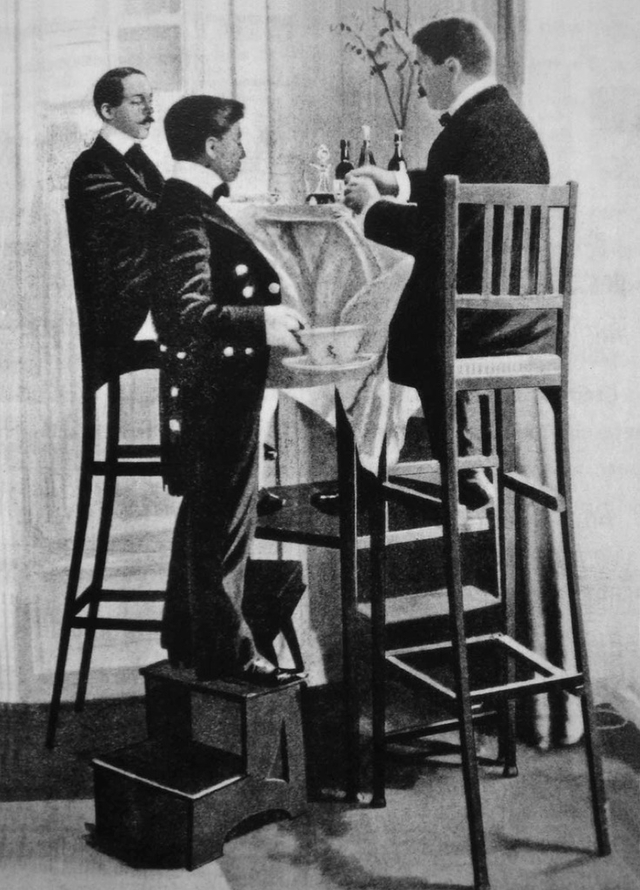

Santos-Dumont did indeed keep fine and noble company at the time, having the highest of European elites as guests in his Parisian home, where he would treat them to “aerial dinners.” His house was outfitted with dinner tables that were well over any person’s height. The chairs were mounted with ladders so that his esteemed guests could climb up to their exaggeratedly tall seating arrangements and dine some ten feet high up in the air. When guests inquired about such peculiar eating arrangements, Santos-Dumont responded coyly (while being so adept at public showmanship, he suffered from crippling shyness) that he just wanted to share with his guests the joy of flying. His guests included European royalty, international journalists, and other celebrities. Hard to imagine barons and baronesses sitting on ten-foot-tall chairs for dinner.

His showmanship and desire to share the feeling of flight led him to be part of many “firsts” in aviation history. In 1903, Aida de Acosta, a wealthy Cuban-American woman of nineteen years was visiting Paris, where she met Santos-Dumont. Fascinated with flying machines, she expressed her desire to pilot the airship herself. Surprisingly, he agreed—and after a few lessons, allowed her to fly it around Paris while he followed her on a bicycle shouting instructions from below (airship no. 9 only had a 3 horsepower engine and could barely conquer a light breeze). This made Acosta the first woman in history to fly a powered aircraft of any sort, some six months before the Wright Brothers first took flight in the United States.

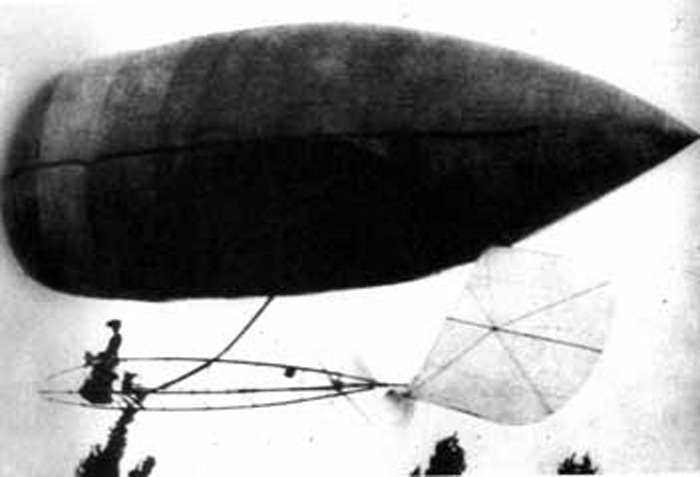

Aida de Acosta piloting the airship. As she landed in the middle of a polo match, everyone cried “Santos! Santos!” Once they realized it was a woman, the crowd started yelling “C’est une Mademoiselle!” Wikimedia Commons

But he also faced criticism that the airship was an unpractical flying device, seen more and more as a novelty rather than a practical mode of air travel. So Santos-Dumont soon turned to the problem of heavier-than-air flight: the airplane as we know it today. Much like many of the aviation firsts at the time, it was fomented by prizes, especially the Archdeacon prize for the first heavier-than-air craft to fly a distance of twenty-five meters.

On October 23, 1906, Santos-Dumont won the Archdeacon prize by flying his Hargrave box kite inspired aircraft at Bagatelle in Paris. He was hailed by many in Europe as the first to fly, despite the fact that the Wright Brothers had achieved such a feat three years earlier in the United Sates. But Orville and Wilbur Wright kept their invention under wraps, avoiding any public exhibitions while they sought a patent. Most aeronauts in Europe considered them to be bluffing.

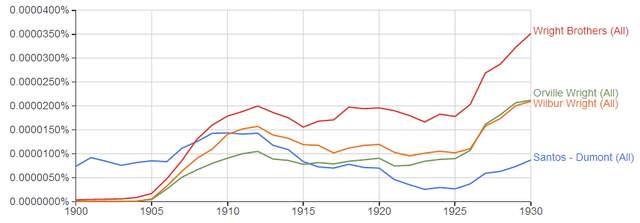

The Wright Brothers would eventually overtake Santos-Dumont as claimants of the first flight. In 1908, they finally demonstrated their aircraft publicly in Europe, assuaging many of their skeptics. A search on Google’s Ngram Viewer tool, a textual statistical analyzer that uses the entire corpus of the Google Books database, clearly shows the rise of the Wright Brothers and decline of Santos-Dumont in the Anglophone corpus:

Frequency of the terms Santos-Dumont, Wright Brothers, Orville Wright and Wilbur Wright respectively in the Anglophone corpus. Google Ngram

But if Santos-Dumont’s popularity and importance as an inventor was diminishing in global aeronautical circles, his star was just beginning to rise in the Brazilian imaginary. There he was a national hero, a larger than life figure, a demi-god.

The Creation of a National Hero

Europe bowed itself before Brazil

And in a meek tone exclaimed congratulations

In the skies a new star shone

There appeared Santos Dumont.

Hail this star of South America

The land of the brave Indian warrior!

The greatest glory of the twentieth century

Is Santos Dumont, a Brazilian!

—Eduardo das Neves, The Conquest of Air (1902)

It all started with the pigeons. Military messenger pigeon number 565, announced at 7:12 am that the fortresses were firing their cannons to greet the steamer Atlantique. At 7:30am, pigeon number 325 announced that the Brazilian Navy’s tugboat, Marechal Vasques, had arrived next to the Atlantique. Such was the excitement and anticipation for his arrival in Rio de Janeiro that a navy vessel carried one hundred messenger pigeons to send updates of the Atlantique’s progress through the ocean. Finally, pigeon number 595 announced what the crowds amassing in Rio de Janeiro’s harbor were waiting for: “Santos Dumont is sitting at the bow, with a wicker hat, using it to reply to the greetings of the military school, the students of which are the first to greet the great aeronaut.”

It was September 1903, and Santos-Dumont was visiting Brazil for the first time as the world’s most famous aeronaut. His reception was nothing short of a massive celebration for a national hero. A journalist claimed it was the “largest popular gathering seen in the capital, which received yesterday the great Brazilian.” A holiday was declared, and all public institutions were closed, with their façades lit with electric lights for the reception.

Incessant shouts of “viva!” followed the large procession, which moved slowly through the crowds. Flowers were thrown upon his horse-drawn carriage at an amazing rate, with one observer noting that every time Santos-Dumont stood up, he looked like a bird emerging “from a nest of flowers.” Every balcony in the route of the parade was packed, and from them rained down a profusion of rose petals and green and yellow confetti.

The celebrations reached a feverish pace. At some point, the crowds attempted to release the horses from his carriage and pull the vehicle themselves. When he left his carriage to speak at one of the many grandstands set up for speeches in his honor, he had to escape the crowds by running and jumping over the median and sidewalk benches, prompting a journalist to comment that he was “agile like a deer.” The number of speeches and odes proffered seemed to also multiply—leading the same journalist to complain that there were just too many, a total of thirteen speeches in a short stretch of the parade route.

The celebrations were certainly as colorful as they were massive—reminiscent of the kinds of parades that received returning astronauts during the early space race, perhaps even more flamboyant. But what does this reception tell us about Brazilian society? What did Santos-Dumont’s achievements, and their reception throughout the world, mean to Brazilians?

Let us take one of the many honors he received as an example. In one of the many celebratory events, a school girl approached him with a bouquet and a message from her fellow students:

Sir, the children from our school are filled with joy to glorify men that have conquered immortality, men that, through their work, their studies, elevate the name of their country in the face of the civilized world. You are one of these great men, a grandiose figure! We, Brazilians, as all sons of this majestic country, salute you!

And there lies the importance of Santos-Dumont in the Brazilian imaginary, an importance that would continue and evolve over the next decades—his power to elevate the name of their country in the face of the civilized world.

Santos-Dumont continued to impress the “civilized world.” His aeronautical exploits allowed people to imagine a new world where air travel might become a practical means of transportation. But for Brazilians, he did much more than elicit a vision of a fantastical world of flying machines. He allowed them to imagine themselves as citizens of a glorious, modern nation—an equal among the world’s powers.

This is particularly true if we consider the context of Brazil’s status in the world at the time. The country was just emerging from a nineteenth century dominated by monarchy and slavery. When Santos-Dumont won the Deutsch prize for circumnavigating the Eiffel Tower in his No. 6 dirigible in 1901, Brazil had only been a republic for a mere twelve years, and had abolished slavery only thirteen years before (the last country in the western hemisphere to ban the ownership of humans). The country’s economy was still centered on cash crops that had long been enabled by slavery, namely its sugar and coffee exports.

Santos-Dumont himself grew up in a coffee plantation, and in his autobiography, he claims that his love of machinery and engineering stemmed from working on all the advanced equipment at the plantation. He was also quite aware that Europeans or Americans might think just the opposite, and to dispel such stigma he made sure to tell them otherwise:

Inhabitants of Europe comically figure those Brazilian plantations to themselves as primitive stations of the boundless pampas, as innocent of the cart and the wheelbarrow as of the electric light and the telephone. […] I can scarcely imagine a more suggestive environment for a boy dreaming over mechanical inventions […] I think it is not generally understood how scientifically a Brazilian coffee plantation may be operated. From the moment when a railway train has brought the green berries to the works to the moment when the finished and assorted product is loaded on the transatlantic ships, no human hand touches the coffee.

There lies the importance of Santos-Dumont as a national idol. He allowed Brazilians to imagine themselves rid of the stigma of backwardness. In the Brazilian imaginary, the nation had just given birth to the greatest technological innovation in history. Santos-Dumont was, to his contemporary compatriots, a ticket to an elite club of nations.

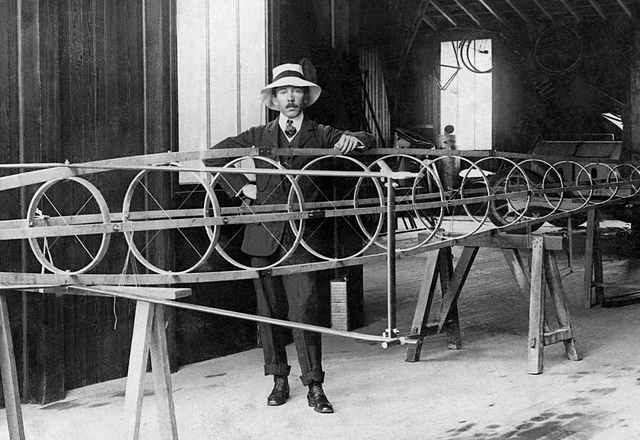

But his flying days were soon coming to an end. After his success with heavier-than-air flight, he eventually produced aircraft no. 20, the Demoiselle. Much like his personal airship, this was a small airplane, the structure of which centered around one single piece of bamboo. It was small and light, and could be carried in the back of his car. But in January 1910, one of the cables holding the wing collapsed, and he crashed from a hundred feet in the air. He survived, but serious damage was done. He soon fell ill, suffering from vertigo and double vision. A doctor diagnosed him with multiple sclerosis. His flying days were over.

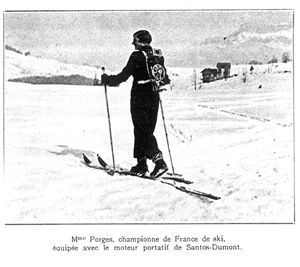

He continued tinkering with many other inventions. One of them was a set of motorized skis to bring him up the mountain—think of it as a personal ski lift, back when there were no ski-lifts at all. There was also a slingshot-like device to throw life preservers from a ship (perhaps inspired by his own experience of crashing an airship in the ocean outside of Monaco). He also created a device for dragging treats around a race-track, to keep racing greyhounds enticed.

But his life was never the same. Flying was his passion. Soon, Santos-Dumont became severely depressed and was mostly a recluse. Despite the fact that he had once volunteered his services to the French military in the event of war (unless it was a war against any nation of the Americas), he now lobbied governments to demilitarize airplanes. The notion that aircraft, “his babies,” were killing people, seemed to severely impact his psyche. He spent most of the 1920s in various sanatoriums in Switzerland and France.

In a visit to Rio de Janeiro in 1920, Santos-Dumont decided to dig his own grave. He selected a plot at a prominent cemetery. He then ordered a replica of the statue that was built in his honor in Paris to be placed at his grave site. He then proceeded to dig, insisting that the soil had to be removed by his own hands. He transferred the remains of his parents to the site, leaving space between them for his own burial.

He left again for a sanatorium in Switzerland, his mental health deteriorating. At one point, according to biographer Paul Hoffman, he even attempted to fly again by strapping wings to his arms and adding a small engine to a backpack. He was stopped by a psychiatric nurse. Needless to say, he was not quite himself. By 1928, he felt well enough to go back to Brazil. Even if much of the world had forgotten him, he was still received with a hero’s welcome in Brazil.

Unfortunately, the hero’s welcome was rather tragic. As his ship pulled into the harbor in Rio de Janeiro, an aircraft made a flyover to greet him. The plane had been baptized “Santos-Dumont” and carried some of Brazil’s most prominent scientists. It was the first time Brazil had airplanes to receive their aeronautical hero. But the plane exploded, plunging into the Guanabara Bay—taking with it Brazil’s scientific elite. He never recovered from this tragedy.

He memorized all the obituaries, and attended all twelve funerals. He once again visited his own gravesite, which he had dug just eight years earlier. Soon Santos-Dumont returned to a Swiss sanatorium.

In 1931, concerned for his health, his nephew went to Switzerland to retrieve him and bring him to Brazil. His doctors recommended that he stay in the tranquil beach resort of Guarujá. But in 1932, civil war broke out in Brazil. The state of São Paulo rebelled against the federal government and its new president, Getúlio Vargas, who had seized power in 1930. This was the first military engagement in Brazil that prominently featured military aircraft.

It seems that the use of the airplane by Brazilians to kill other Brazilians severely depressed him.

According to the testimony of the elevator operator at the hotel, the last person to see him alive, Santos-Dumont’s last words were “I never thought that my invention would cause bloodshed between brothers. What have I done?”

He was known as an impeccable dresser, a fashion trendsetter. But he had not worn a suit for many months during his severe depression. He went into his closet, and donned a suit. He went into the bathroom. He then found two red ties he used while flying in Paris. He tied them around his neck, once again looking like the debonair bon-vivant aeronaut he once was in the city of lights. He stood in a chair. But this time, he let the chair (not a seven-foot aerial dinner chair, just a regular chair) slip from under him. The fashionable red tie tightened around his neck. For a man who so many times defied gravity, he now just let gravity do its work.

It was July 23rd, 1932. Santos-Dumont hanged himself in Guarujá. He died closer to home, yet far away from his days of glory in Paris.

Brazilians could hardly admit that their hero had killed himself. The authorities obscured that fact, claiming cardiac arrest. The medical examiner knew better. But he was also left alone with the body for just long enough … just long enough to remove his heart, and preserve it in a jar full of formaldehyde. Just over a decade later, the doctor felt some remorse. He attempted to give the heart back to the Dumont family.

But they would not have it. It must have been too painful.

So the heart was donated to the Brazilian government. Eventually, it was put in a display at the Air and Space museum. And it stands there to this day. A religious relic in the temple of aviation. A small piece of one of the most beloved Brazilians in history: a saint, as far as any Brazilian is concerned. And what other church could be a better place for the heart of Saint Santos-Dumont.