On Looking: Friendship and the New Haven Green

Barber, J. W. E[ast] view of the public square, or Green, in New Haven Con[necticut]. Published and sold by J.W. Barber and by the booksellers in New Haven. 1831 & 1846

But you are here

for the story…

So it is a lost story

but we will be imagining it, anyway.

—Rita Dove, “Prologue of the Rambling Sort”

Many things are true at once.

—Elizabeth Alexander, “Amistad”

It’s summer, this evening. And it’s perfect. We’ve been waiting for weeks to call it that. This is our time to shed the Beinecke Library’s hunched and treasured promise. We nervously joke about whether the cameras over our shoulders are really watching us—even as we know their presence is about protecting the 500,000 volumes and millions of manuscripts housed here. We’ve put in our day’s hours, combing through Richard Wright’s papers and Langston Hughes’s meticulously catalogued correspondence, grateful for the intimate distance of handwriting curated across time. Once outside, we are grateful anew for the stretching of limbs and the city’s trafficked chatter.

This is the kind of twilight I want to put my skin against: seamless. I’m thankful for a friend I can set my whole self down in, and there you are, walking just a little bit ahead of me, down Chapel Street—past the coveted Lithuanian coffee cake at Claire’s Corner Copia, past the boutique stores that don’t seem to sell anything in particular, so much as to mark this street (at least those parts that shine behind glass) as the purveyor of excess—what Amanda Erickson must be referring to when she proclaims in The Washington Post that New Haven has “outgrown its reputation as a college town that’s more crime than coffee shop.”

In her gloss on this city’s history of the past sixty years—speaking back to an identity accruing since the wake of WWII, when manufacturing jobs plummeted and urban violence climbed—Erickson flippantly muses: “[O]n a recent weekend trip, I discovered that this New Haven doesn’t really exist any more (if it ever did).” If it ever did.

The constellation of burgeoning galleries and coffee shops that have ridden the aesthetic coattails of industrial renewal seem to induce not only blindness, but also amnesia—corralling the city’s present and multiple histories into an asset that is literally available for consumption: “divey ethnic food options.” For Erickson, these diverse eateries exist to bolster the city’s emergent “quaint”-ness and “historic charm.” This is our geography, even as we lament Yale’s encroachment on the rest of the city.

“Can you really know anything about the subjects of Wright’s interviews from his papers?” You wonder aloud, reflecting on the day’s research. We’re walking side-by-side now, and your voice gathers me from the city’s diffuse soundscape, drawing me into focus. You’re frustrated that Wright’s reflections on the 1955 Bandung Conference, which brought together the leaders of twenty-nine African and Asian nations, are a shadow screen on the South Asian subjects you want to engage. His archive testifies to their presence, even as his aggressive overwrites hold at bay a subjectivity that is not Wright’s, filing the contours of their personae against the cookie-cutter imposition of Orientalism. “Since I had resolved to go to Bandung, the problem of getting to know the Asian personality had been with me day and night,” Wright laments. “Knowing that I had no factual background to grapple with the swirling currents of the Asian maelstrom, I had weeks before devised a stratagem to enable me to grasp at least the basic Asian attitudes.” You spend the day coaxing dimension from Wright’s writing, reading the vectors of his desire like a map. Maybe the spaces between drafts will reveal the shapes of his erasures, you hope, opening up the carefully kept boxes of papers and trying to find a way to read otherwise.

This city is restless. The Dead Shall Be Raised, proffers the Egyptian revival arch that presides over the Grove Street Cemetery. America’s first chartered burial ground and the first cemetery to organize its burials by family, the Grove Street Cemetery was founded in 1796 when the previous burial site, the New Haven Green, became overcrowded after the preceding years’ yellow fever epidemics. The tombstones were transferred to Grove Street, but the bodies remain interred in their original place. Two years ago, Hurricane Sandy exhumed a skeleton from under an oak tree planted in 1909 in honor of Abraham Lincoln. New Haven seems to want to unbury itself.

We cross the street, heading left onto the Green. So often, the sixteen-acre park seems a place of two speeds: a granter of shortcuts for those who have elsewhere to be and a dwelling place for those who have nowhere to go. But now, transformed, it is the city’s pulsing heart. The International Festival of Arts and Ideas promises us fifteen days of “performing arts, lectures, and conversations that celebrates the greatest artists and thinkers from around the world,” and some of its best events are held right here.

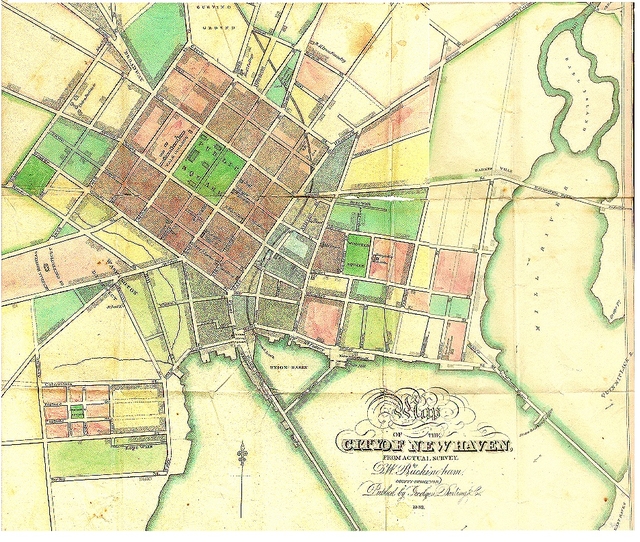

Map of the City of New Haven, from actual survey, Connecticut, D.W. Buckingham, 1830. Sterling Map Collection, Yale University

L’Homme Cirque. The one-man circus. The tickets are either full price ($35) or pay-as-you-wish. Between us, we pay $3 and feel generous when the teenager in the ice cream truck ticket booth tells us he has received donations starting at twenty-five cents. He motions behind him, to the tent set up on the Green. When we enter, it smells like elephants.

This evening, there is only one vested man. L’Homme Cirque. He is trainer and trick. His instruments: treadmill; tightrope; wooden horse. His exaggerated gestures forgo language. He seems at once impossible and inevitable, as though he might at any moment burst into a backflip.

We take our seats. There is a cannon off to the side. A small boy in a kippah covers his ears with his whole and flat hands. The fits and starts that jolt his small body are not correlated to anything visible to me. He knows these spaces are prone to eruption. There is a slim girl, who fidgets with the edges of her veil and smiles widely when a friend on either side leans in to whisper in her ear. There are teenagers on a date—grateful to have something they understand as harmless to cast their laughter on. And their fear, mock with a copper thread of truth. She buries her head in his shoulder because she wants to bury her head in his shoulder, but the man balanced on the tightrope is a delicate and beautiful excuse.

There is a chorus of kids who are young enough to fall noisily for the illusion. “Ewwwww.” Their voices come loud and high from every direction when a brown wooden ball drops from the fake horse. The kids who are just a little bit older—the ones who totter unstably on illusion’s edge—are afraid not that the poop is real, but that they alone are the ones that see through. Or, worse, that everyone else shares this knowledge but assumes that they don’t. “That’s not real! They know that’s fake, right?” They say, tugging on the sleeve of the nearest adult.

A small child whimpers when L’Homme Cirque tries to engage her, offering an amplified and quizzical glance. The child’s mother offers the performer a consoling look before taking her daughter outside. (I wonder, suddenly, whether he’s lonely; whether he feels this as a loss, the children being taken to an outside where protection trumps entertainment. Does the creation of this magical space lock him into his own boundaries?) The tent is small enough that I feel seen watching, responsible to the man for the way I’m looking at him. I’m glad for the sureness of you next to me. “It’s magic,” we say to each other, over and over again, knitting the night into a memory we know we will want to hold.

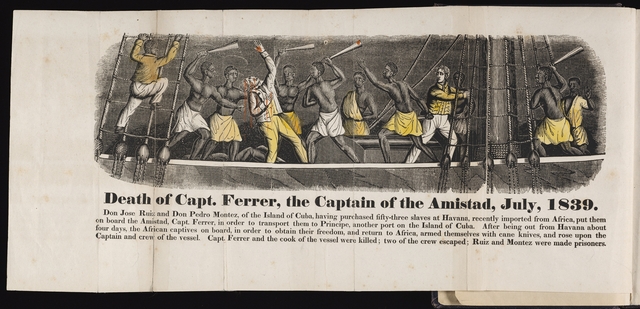

In 1839, people from the Mende ethnic group were abducted from their homes in today’s Sierra Leone and transported across the Atlantic to Havana, Cuba. One of the women who had been captured found a metal file on the ship. The woman’s name has not been kept. The ship was named the Tecora. The Tecora docked in Havana—nearly five thousand miles from her home—where the woman-whose-name-has-not-been-kept disembarked, keeping the file close and hidden, even when she and fifty-two of the people who had been illegally captured and brought across the Atlantic were purchased by Don Jose Ruiz and Don Pedro Montez. Ruiz and Montez put the Mende captives on yet another ship.

Shuttles in the rocking loom of history,

the dark ships move, the dark ships move

their bright, ironical names

like jests of kindness on a murderer’s mouth…

La Amistad. Friendship. The name of the two-masted schooner destined for Havana, the second vessel of the Mende captives’ illegal transport. The woman brought the file, which she gave to Sengbe Pieh, one of her fellow captives. Sengbe used that file to cut himself free and then to cut the chains from the bodies of his fellow slaves. They killed the ship’s captain, half of the crew, and Celestino, the mulatto cook. He had threatened the Mende captives that they would be eaten. They spared the navigator and commanded him to sail east, back to Africa.

Frontispiece from J.W. Barber’s A History of the Amistad Captives: Being a Circumstantial Account of the Capture of the Spanish Schooner Amistad, by the Africans on Board. Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University

The navigator directed the ship north and west. The ship was adrift for two months before the US Navy apprehended the vessel off the coast of Long Island. Were the captives free men who had the right to defend their freedom? The case was the nexus of numerous debates. The “symbolic fight to reconfigure the nation’s understanding of democracy” unified a fracturing abolitionist movement. Taking center stage in domestic disputes between abolitionists and advocates of the ‘peculiar institution,’ the case also implicated international debates about the global routes of slavery. President Martin Van Buren, galvanized by an impending election, sought to bolster his popularity in the Southern states and brought the case before the US Supreme Court in 1841. John Quincy Adams came out of retirement to represent the Mende captives on board the Amistad. The United States v. The Amistad.

And the Amistad captives waited, kept in a jail on the New Haven Green. For twelve-and-a-half cents, residents of the city could come look at them.

William Townsend was eighteen years old. He came to look and made pen-and-ink drawings of the Amistad captives while they were awaiting trial. In 1934, a relative of Townsend’s donated twenty-two of these drawings to the Beinecke Library. Eighty years later, I am running my finger across the sketched face of a little girl and wondering what the reliefs of her imagination looked like. What did she make of this white boy-on-the-hinge-of-manhood, come to draw her? What did he want of her picture? Did she see in his image anything of herself—anything of her mind in this head that floats on the paper like a matte phantom?

William Townsend, Marqu. ca. 1839-1840. Pencil drawing, 16.5x13.8 cm. Townsend, William H. Sketches of the Amistad Captives (Marqu). ca. 1839-1840. Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University

We see first and deepest who we might closest be, if not ourselves—your eyes on the round brown face of a wide-eyed child whose mother’s thin fingers show him the way: look at that! His path to L’Homme Cirque is laced with her elegant gesture. The frightened little boy’s kippah commands my gaze. We have learned to look. For pride? Protection? How do we understand ourselves in these closenesses?

When I graduated college and found myself in South Africa and lost between work and the room I’d rented, my mother said: find a door with a mezuzah, and knock—like that marked prayer makes my closest neighbor. It is the same year that Leiby Kletzky, an eight-year-old Hasidic boy found his murderer in Boro Park, Brooklyn. July 11, 2011; Leiby’s first day walking alone from camp to a point where his mother had agreed to meet him. They had practiced the walk together the day before but, by himself, he has lost his way. He stops to ask direction from Levi Aron. A kippah on both heads, their shared marker toward God. Surely this man knows the way; he will point the boy safely toward home.

But it is only tonight, and we are here. We’ve just sat down in this magical tent on this magical evening, and I am looking first at this beautiful boy in the kippah whose sister calms him with a hand on his shoulder, and I am whispering, achot, sister, so quietly it fills and never leaves the home of my mouth, this word that fits my tongue.

Jose Ruiz changed Sengbe’s name to Cinque, the Spanish name meant to suggest that he had been born into slavery in Cuba, where slavery would not be abolished until 1866. If only Ruiz could rub away the Mende name, make him Cinque—born black in Cuba—he and Montez would have been within their legal rights to take him.

What can we find of this man in these kept files? We write back to Montez and Ruiz: Sengbe. No, Cinque is not his name. He was not born into your language. But Sengbe, too, is only an approximation of the Mende. Did he ever hear this name as his? If Sengbe refuses to fold to Ruiz’s scheme, it also marks the limits of my tongue’s empathy.

I will be called bad motherfucker.

I will be venerated.

I will be misremembered.

I will be Seng-Pieh, Cinqueze, Joseph,

and end up CINQUE.

In the 1830s, every freshman entering Yale College knew Latin. They anchored their tongues in a transatlantic claim to civilization. They watched the return of Halley’s comet through a 5-inch Dollond, the most powerful telescope in America. They saw furthest. They made sense.

A is for abolitionism, the first entry in the Dictionary of Afro-American Slavery.

“Throughout British North America, formal opposition to slavery was rare outside of the Society of Friends (see Quakers).” See, Quaker abolition movements believed that black people should neither be slaves nor fellow citizens. What of the “formal opposition” of enslaved people? F is not for file, the kept-close and way-making tool Sengbe used to render useless his chains. Elizabeth Alexander writes:

The historian laments caesuras in the historical record; the artist can offer deeply informed imagining that, while not empirically verifiable, offers one of the only routes we may have to imagine a past whose records have not been kept precious.

What opposition? Whose form?

The deep immortal human wish,

the timeless will:

Cinquez its deathless primaveral image,

life that transfigures many lives.

Voyage through death

to life upon these shores.

The Green continues to serve as a central node around which the city grows and develops. “New Haven Green.” 41°18'29.37" N and 72°55'34.05" W. Google Earth, March 29, 2012. February 12, 2014

With comic grace and clipped exactitude L’Homme Cirque runs a match up the side of the cannon and tucks himself into its narrow shaft. He is ejected and lands with impossible precision on a high wire. A trickle of blood down his scalp blunts our applause—not knowing, at first, whether this is part of the stunt and what our clapping, if offered, would affirm. The air is hazy and thick with the dangerous magic of our not-knowing. We are the child saying “They know that’s fake, right?” and fearing the consequences when there is no one to oversee the boundaries of our uncertainty. But it is softer, somehow, the edges of danger dulled by collective confusion.

L’Homme Cirque climbs through a flap in the top of the tent, and we gather outside to watch him, placing one foot slowly in front of the other, into the red and dusk of sky; we are woven together by our uneasily shared spot of looking—though I wonder how often I have stood on the Green with these or other people before and not thought of our jagged intimacy. From where we stand: the bloody scalp invisible, its health restored by our distance. He is only the miracle pressed into the blanket of twilight. The sky is purple and orange and he is walking up into it. Slowly, he turns around and takes a photo of us watching and waving and wishing him well.