Letter from the Editors: Bodies

Leonid Rogozov removes his own appendix—”the cursed appendage”—in Antarctica, 1961. Wikimedia Commons

In April of 1961, a twenty-seven year-old surgeon named Leonid Rogozov took a scalpel and sliced open his own abdomen, watching, in a mirror, to make sure that his hand didn’t slip and damage the organs inside. He and eleven other Russians were in Antarctica, in a base beyond the help of any other doctors, and Leonid had been feeling sick for days. It was appendicitis, he had realized, and he needed to operate on himself before that strange, vestigial organ—otherwise ignored—ruptured. Reclining on the operating table, dressed in both surgical mask and patient’s smock, doctor and doctored, he rummaged about in his insides, without gloves, feeling for the inflamed organ, growing weaker and weaker.

“Finally, here it is, the cursed appendage!” he later wrote in his journal.

With horror I notice the dark stain at its base. That means just a day longer and it would have burst … At the worst moment of removing the appendix I flagged: my heart seized up and noticeably slowed; my hands felt like rubber. Well, I thought it’s going to end badly.

It didn’t. Rogozov successfully excised his appendix, lived on, and died in 2000. His journal got a nice swell of attention a few years later, after an article about his auto-appendectomy co-written by his son, Vladislav, appeared in the British Medical Journal. We at The Appendix have avoided writing about Leonid’s lost organ until now for obvious reasons—a little too on the nose, yes—but also because we were saving it for this, our long-planned sixth issue, ‘Bodies.’

With apologies to Raymond Carver: what do we talk about when we talk about history? Politics? Religion? Economics? Culture? But what about that bright sharp knife pressed—cold, hard—into our own warm skin, and the blood that wells up after?

It is very easy for history to untether and float away into abstractions; but it is far harder for it to do so when we remember that history, no matter what, happens to bodies. Not just our own, but those of others, and indeed of other species, bodies of water, planetary bodies, and so on. History itself is a body of knowledge. There’s abstraction here too, but it’s a useful abstraction. It suggests the connectedness of the body being considered: its ability to be born, live, and change. Its sensitivity to foreign objects, and the complexity of the organs it contains—ignored organs, sometimes, that might just go corrupt and provoke the death of the body entire.

Bodies. We have them, and we see and make them everywhere we go. As much as we try and divide, and distinguish, we ultimately come back to the core fact that all of us have a heart that, for some short spell of eternity, will pump blood out over our skin and into the world.

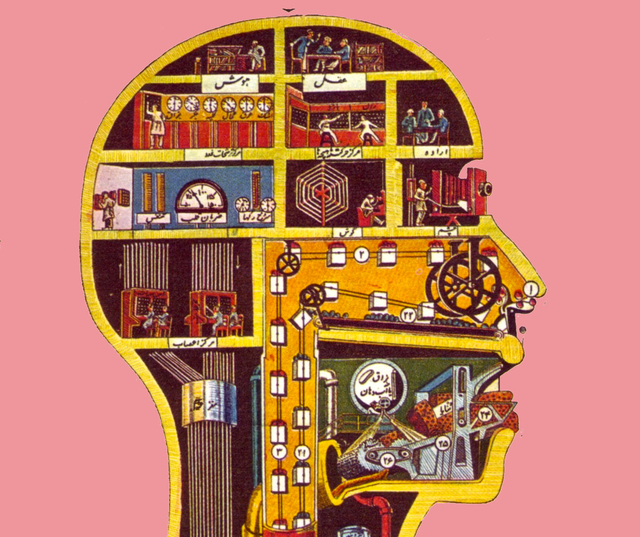

A Persian version of Fritz Kahn’s famous “Man as Industrial Palace” image from 1967. Machinatorium

Chapter One: Human Bodies

Bodies in the world of classical antiquity, writes Peter Brown, were “little fiery universes, through whose heart, brain and veins there pulsed the same heat and vital spirit as glowed in the stars.” The microcosm of the human frame mirrored the macrocosm of the universe. But this tidy of the conception of the body hides the complexity of what it means to be a physical being: as the eight pieces in chapter one of this issue explore, every human culture and epoch has embodied itself in different ways, from preserved hearts to barbered beards, and from Panamanian blood-letting to Pennsylvania mugshots, scurvy sailors, and early modern apothecaries.

Chapter Two: Bodies on Display

When the South Asian ruler Tipu Sultan commissioned a pipe organ in the shape of a tiger mauling an Englishman, what precisely was he doing? That’s the question posed in “Robot of Jihad,” but it also informs the other pieces in this chapter. From extinct species given new life to cuts of meat in an icebox and the skulls in a museum, bodies on display speak a language of their own. They can be assertions of will, or threats of violence. And the memory of their display often outlives the bodies themselves.

Chapter Three: Foreign Bodies

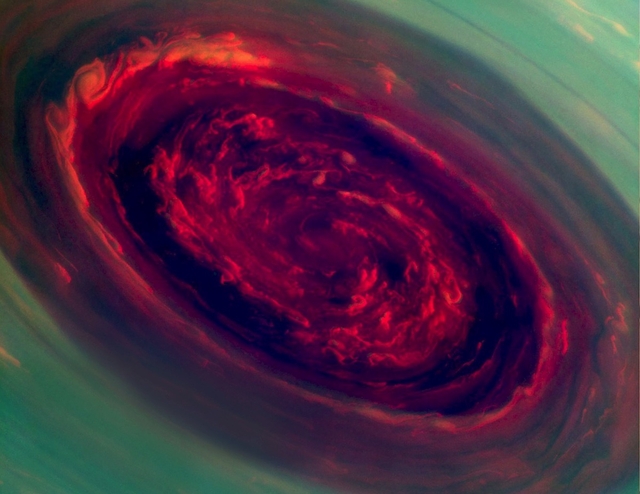

Bodies, by their very nature, occupy a liminal space between the inner world of the mind and the external cosmos. They are gatekeepers, fighting off fevers, negotiating linkages between mother and child, or transmitting the sensory world to the brain. Yet there are other kinds of foreign bodies: in the realm of religion, we envision mystical resonances between bodies at a distance, and in bodies of water we search for unfamiliar creatures. Beyond our sublunary sphere, cosmic bodies survey it all, forever out of reach.

“What it is like to be a human being, or a bat, or a Martian?” the philosopher Thomas Nagel famously asked in 1974. His conclusion? Every experience of selfhood is based on “facts that embody a particular point of view.” To have a body, to inhabit it, to experience reality through it, is the core of our consciousness—what makes an experience ours, and not someone else’s. Our bodies both instruct and construct us.

Here’s hoping that the body of work in this issue does the same.

Your Appendix editors,

Benjamin Breen

Felipe Cruz

Christopher Heaney

Brian Jones

Amy Kohout

Lydia Pyne