Mug Shots: A Small Town Noir

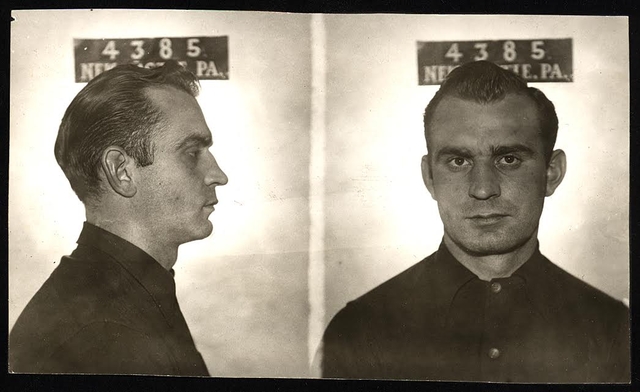

Floyd M. Armstrong, arrested for loitering (and possibly stealing a roll of pennies and a box of shotgun shells) on a summer night in 1957, in New Castle, PA. Diarmid Mogg

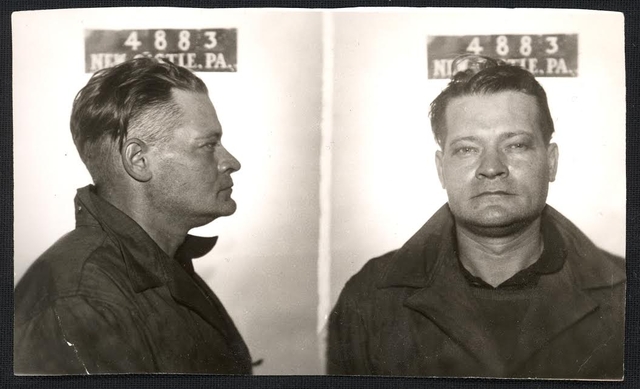

Martin Fobes woke up to the sound of officers from the New Castle police department banging on his front door.

It was early on a January morning, still dark, and he was lying flat on his living room floor, where he had passed out a few hours previously. The police took him downtown and charged him with driving while intoxicated. They sat him in a chair against a white wall and slotted numbered tiles into a board behind him, to record the fact that he was the four thousand eight hundred and eighty-third person to have been processed in that room. They took a picture of his profile, then turned him to take a picture face-on. While he was held for questioning, the negatives were developed and printed on a small piece of photographic paper that had been cut with scissors from a larger sheet. The print was then taken to a room in police headquarters known as the rogues gallery, where it joined the ever-growing archive of twinned portraits of citizens unfortunate enough to have been caught breaking the law in Lawrence County, Pennsylvania.

Sixty-one years later, the photograph dropped through my letterbox in Edinburgh, Scotland, in an envelope containing half a dozen old mug shots that I’d bought for a few pounds from an eBay seller who specialized in historic ephemera.

I’d become interested in mug shots through a book called Least Wanted, by Mark Michaelson, which contains hundreds of these strange and beautiful little portraits, taken as a matter of routine by law enforcement agencies across America but made haunting by the passage of time. I was fascinated by the range of expressions, the haircuts, the clothes. Such faces. Who were they? What had they done? What were their lives like?

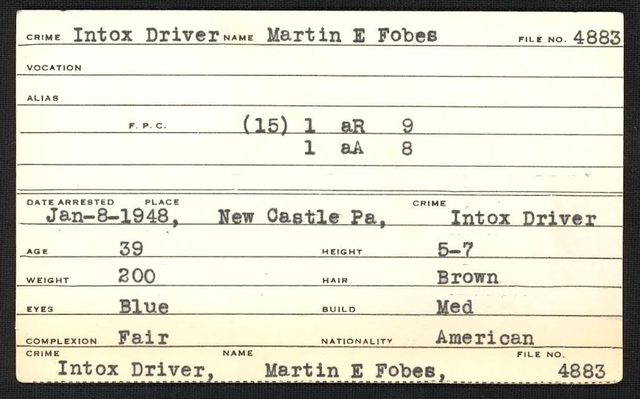

Almost all of the pictures in Least Wanted are anonymous, having become separated from their arrest information due to the carelessness of police departments, dealers, and collectors. Part of the reason why I bought the bundle from eBay was that the listing noted that they still had their police file cards attached, and I hoped it might be possible to use that information to find out more about the people in the photographs.

Each of the six cards listed various pieces of information, including, importantly, the person’s name and age, the crime with which they had been charged and the date and place of their arrest. All six people were from the same town: New Castle, Pennsylvania, a place I’d never heard of. I checked NewspaperArchive.com and saw that its database contained back issues of the local paper, the New Castle News, going back over a hundred years. A promising omen.

Martin’s mug shot was on top of the pile, so I ran a search on him first. His name appeared in the paper about thirty times over fifty years, from the announcement of the birth of his daughter in 1929 to his obituary in 1969. Most of the mentions were in the paper’s local events pages, where he appeared among lists of routine hospital admissions or as a pallbearer at the funerals of friends and relations—commonplace traces of a normal life.

The articles that came up for the month of his arrest, however, were a different matter: two front-page stories in one week, headlined, “Officers Probe Woman’s Death” and “Cause Of Girl’s Death Is Mystery.” I hope I can be forgiven for feeling a thrill of excitement as I scanned the pieces and saw Martin’s name emerge as part of a far more intriguing story than I’d been expecting. An unconscious eighteen-year-old girl named Anna Grace Robertson had been found lying in the middle of the street, battered and bleeding, in a residential part of town on the morning of 6 January, 1948. The police who woke Martin up from his drunken sleep and took his mug shot told him he had been seen with her that night. Martin said he remembered leaving the Rex Café with her and her sister sometime after midnight, but nothing after that. He had no recollection of how he ended up back home. He had blacked out. He didn’t know what had happened to the girl.

Anna Grace never regained consciousness. She died three days later, after being admitted to the hospital. A post-mortem found the cause of death to be hemorrhages of the brain. She also had a complete fracture of the left jaw, partial paralysis of the left arm and left leg, and friction burns on her face and right knee.

At the inquest, Martin said, again, that he had no recollection of what had happened that night. Others filled in some of the blanks.

Anna Grace’s sister, Eris, said that Martin had taken her and Anna Grace home from the Rex Café, where they had met him. Anna Grace knew Martin, it seemed, but Eris had never seen him before. When they got to the house, instead of coming in with Eris, Anna Grace went off with Martin. They said that they were going to a café called Jim’s Place on the east side, and were then going to the Square Deal café to meet Anna Grace’s mother, who worked there. It was half past midnight.

The bartender of the Rex Café, William Weidenhof, had gone over to the Square Deal after closing up his place, and saw Martin and Anna Grace there. Martin was drunk, and kept asking Anna Grace to leave with him. Eventually, just before two, Weidenhof saw Martin take Anna Grace’s arm and lead her to his truck.

About twenty minutes later, a man called Louis Smith found Anna Grace lying in North Mercer street, unconscious, with a bloody nose and a bruise on her forehead. He called the police, and an officer took her to the hospital.

People who had met Martin in town the next night, back in the Rex Café again, told the inquest that he seemed “pretty well loaded” and had scratches on his face. A friend of Martin’s, Joseph McKee, asked him if he knew what had happened to Anna Grace, but Martin ducked the question, saying only that he had been in a wreck at the harbor at about half past four in the morning, but that everything was “on the up and up.” Later that evening, he passed out in the bar.

At the end of the inquest, the members declared that they were unable to determine how Anna Grace sustained the injuries that caused her death and recommended further investigation. There was none. Anna Grace had already been buried, the witnesses had said all that they could and Martin Fobes wasn’t saying anything else. The case appears to have been dropped. The paper doesn’t mention it, or Anna Grace, again after that day. Martin was charged only with leaving the scene of a crime.

No one seems to have been certain what happened in the missing twenty minutes between Martin and Anna Grace leaving the Square Deal and Louis Smith finding her in the street. Anna Grace’s injuries suggest that she jumped from Martin’s speeding truck, but why did she jump? The most likely scenario would seem to be that Martin made a move on her as they drove through town, they struggled (which would be when his face was scratched) and she jumped from the truck to escape. That must have been obvious to anyone involved in the case but, if it occurred to the inquest’s members—all men—they chose not to pursue it. Perhaps it struck them as just a tragic accident, and not the kind of thing over which they should ruin the life of a hard-working family man.

I realized, of course, that it was impossible to say for sure how culpable Martin was, and also—at this date—quite unnecessary to try. The story itself was enough for me. I wrote it up and posted it online. It was the start of a project that would end up occupying all of my creative energy for years to come, in the form of a website called Small Town Noir, which has evolved into an attempt to chronicle the history of one small American town through the criminal records of its citizens.

None of the other mug shots in the bundle matched Martin’s for dramatic incident, but I researched the subjects’ lives as fully as I could, with a growing sense that I’d stumbled on something unique and valuable. By the time I was done, I’d uncovered a good few compelling stories and read an awful lot of old copies of the New Castle News—enough to make me feel that I’d perhaps caught a glimpse of something that might be more interesting than the stories themselves: the town in which they took place.

Like me, you’ve probably never heard of New Castle. It sits midway between Lake Erie and Pittsburgh, over by the Ohio border. It was founded after the Revolutionary War, in a valley that had been settled by the Lenape people, before they were forced out. Its growth was phenomenal. In the 1890s, its population increased by 144 per cent, faster than any other town in the country. By the turn of the century, it was one of the most industrially productive cities in America, with the biggest tinplate mill in the world and thousands of immigrants from Europe arriving every year to work in its steel factories, ceramics plants, foundries and paper mills.

All that’s gone now, of course. The Great Depression hit it hard, and the disastrous collapse of industry in the Northeast in the latter half of the century all but finished it off. Its present population is around 23,000, down from a wartime peak of nearly 50,000. You can imagine what the depopulated parts of town look like these days.

Yet something about New Castle captured my imagination. The place names—Locust Street, Croton Avenue, Shenango, Neshannock—were powerfully evocative of a certain idea of America, although one that, in all honesty, probably exists only in the minds of Europeans like me, whose imaginations have been shaped by a love of B-movies, pulp novels and old crime stories. None of the people in the photographs would have looked out of place working in Robert Mitchum’s garage in Out of the Past or hiding out in the boarding house where Burt Lancaster is murdered in The Killers. The more I learned about their world, the more their lives began to feel like the back-stories of minor characters in a richly detailed film noir that Hollywood had somehow neglected to make.

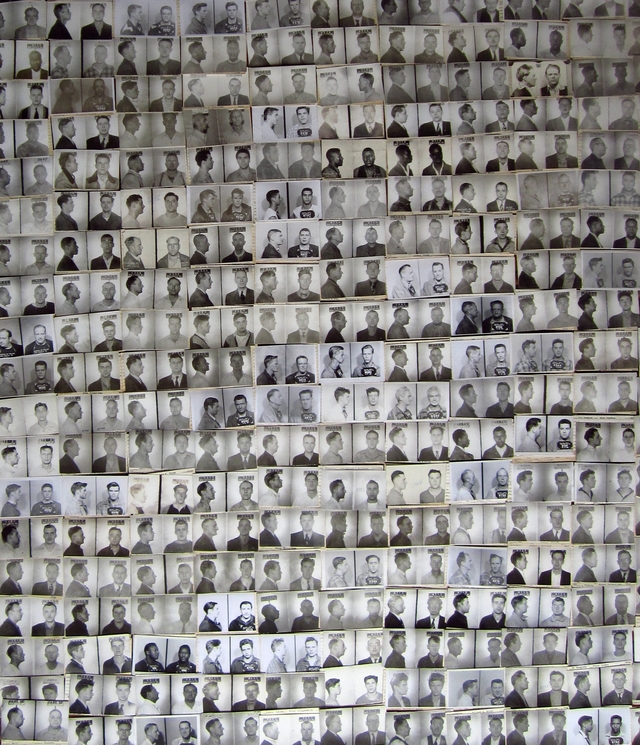

There were more New Castle mug shots on eBay, all from the decades between 1930 and 1960, and I bought as many as I could. The pictures had ended up all over the world—San Francisco, Tokyo, even a small island off the coast of Scotland. I always asked the seller how they had originally come by the pictures. The usual answer was that they’d bought them from other collectors. No one knew for sure how the photographs had first ended up for sale, but I gradually worked out that, sometime in the 1990s, the police department had cleared out its files and thrown hundreds—maybe thousands—of old photographs in the trash. A few hundred images were surreptitiously saved from destruction by a police officer nearing retirement.

The ones he picked up happened to come from the middle decades of the century. If he had passed by earlier, he might have come away with a selection from around the First World War. Later, and he might not have found any at all.

My collection grew over the next few years. Each batch—still carrying the strong smell of the cigarettes smoked by New Castle detectives over the years—brought to light wonderful characters: a quarry worker who was arrested after losing his false teeth at a crime scene; a prohibition agent whose house was dynamited by bootleggers; an upstanding poultry fancier who turned bank robber; immigrant families; civil war veterans; local capitalists; and a lot of drunks. And each research expedition into the archives of the New Castle News revealed more about the town and its history.

During the period I was interested in, the New Castle News was one of those local newspapers that aimed to provide an indispensable daily record of the comings and goings in the communities that they served, along with a couple of pages of national and international news and opinion from the wire agencies.

Naturally, it reported on local politics and social events to an exhaustive degree. (It regularly included, for example, full descriptions of services in the town’s churches and synagogues.) Mixed in with those stories, however, are small impressions of everyday life that it’s hard to imagine finding in any other source. A few examples:

Over the week-end a couple of strange sights were seen on the streets of New Castle. One: a man was noticed mowing his lawn long after darkness had surrounded him. The other was a young girl running in the midst of a heavy downpour of rain with an unopened umbrella under her arm. (May 4, 1936)

Pa Newc saw a rather odd sight in the seventh ward yesterday. A man was driving a car which had a sign labelled ‘Funeral’ fastened on the wind-shield while fastened on the back end of the car was a trailer which had a large quantity of sheep’s wool loaded on it. (September 24, 1924)

The mystery of who it was who put the pigeons in one of the court house desks is still unsolved. The act is denied by all. (January 7, 1930)

Those details are gold, to me, and I make sure to include as many of them as I can when I write up the stories of the people in the mug shots. The fact that, on the night in 1943 when a man named Frank Heckathorn was arrested for indecent exposure, posses of youths were searching the town’s cemeteries for signs of a supposed half-man, half-beast mutant that they believed had been spotted waddling menacingly in the area strikes me as being just as relevant to the story as the country’s import/export balance for the year or what Patton was doing in North Africa.

What’s more, including that day-to-day perspective reduces the focus on crime. New Castle wasn’t a particularly crime-ridden place. And, although my point of entry into the townspeople’s lives is always, unavoidably, a criminal act that they’d been charged with, the majority of them couldn’t be described as criminals. They were ordinary people, by and large. Like Charles Cialella.

Charles played football for New Castle High and worked for his family’s florist business until he joined the Army Air Service, immediately after the attack on Pearl harbor. Two months after the end of the war, he was arrested for playing a numbers game. His mug shot was taken and put on file, but he was released without being charged.

He went to work with New Castle’s parks department and became supervisor of the Cascade Park swimming pool when it reopened in 1952, offering a pledge that, following a program of improvements, it would now be impossible for bathers to contract skin diseases or sinus trouble through use of the facility.

In 1968, Charles’s cousin, Carl, became mayor and appointed Charles superintendent of all the city’s parks. By the seventies, the administration had changed and Charles was made foreman of the city’s sewers. In 1976, he was working in a sewer in Winter Avenue when he found a 1942 class ring inscribed with the initials MAS hanging on a broken tree branch. He called New Castle High, whose staff checked their records and told him that it must have belonged to Mary Agnes Schetrom. Charles’s friend, Frank Gagliardo, had been the Schetrom’s paper boy and still knew some friends of the family, who told Charles that Mary Agnes was living on Kenneth street. Two hours after he had found the ring, Charles returned it to Mary Agnes, who told him she had accidentally dropped it down her toilet thirty years earlier and had not expected to see it again.

Charles was a Republican committeeman and president of the local lodge of the Sons of Italy. He played golf, went bowling and raised funds for charity. His wife bred exotic plants and worked as an Avon representative for fifty years. They raised five children and were both over eighty when they died.

Ordinary people.

Since I started researching and publishing the stories behind the mug shots on the Small Town Noir website, I’ve visited New Castle a couple of times, tracked down crime scenes, met relatives of the people I’ve written about—I’ve even attended the 95th birthday party of a man who had his mug shot taken at the age of seventeen, in 1935, when he was charged with stealing a car. (The return of his mug shot was my birthday gift to him.) Over those years, I’ve come to feel something like love for New Castle and the people whose lives I’ve tried to piece together.

The subjects of the mug shots were, for the most part, largely innocent of wrong-doing, aside from an occasional error of judgment or alcohol-induced indiscretion. They were citizens of a town—perhaps a nation—that was unaware it was experiencing its golden age. They worked in vast production lines. They shopped in crowded streets. They marched with their fraternal organizations to the music of faraway homelands. But they raised a generation of children who would grow up to find out that the place that had given their parents and grandparents everything they had in life was gone.

The steel mills have closed now, the downtown sidewalks are deserted. The men and women in these pictures saw things that none of us will ever see. All that we can do is look clearly at their faces, listen carefully to their stories and let them tell us what they can about their world, and what life was like in that long-gone town.