Elegy and Effigy

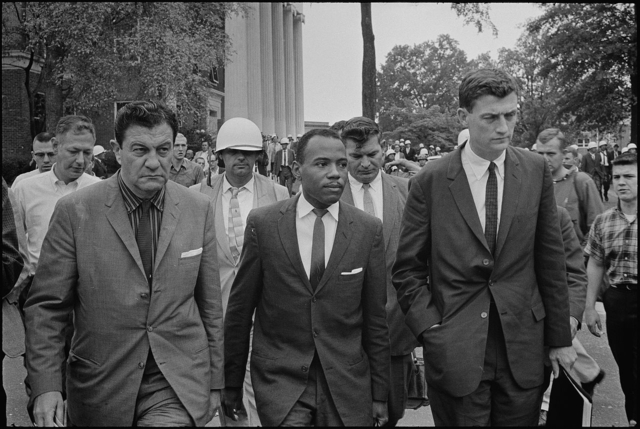

James Meredith (center) received hundreds of death threats when he integrated the University of Mississippi in the fall of 1962. His fellow students greeted him with taunts and jeers, but also with effigies they hanged and burned to register their disgust with his presence on campus. He spent the rest of his time at the university flanked by U.S. marshals charged with ensuring his safe passage around campus. Wikimedia Commons

An effigy dangled outside the second-story window of Vardaman Hall, a men’s dormitory on the University of Mississippi campus. Its head crooked from the rope tied around its neck, the limp figure wore a sign that read “GO BACK TO AFRICA WHERE YOU BELONG.” Tucked inside the back of the collar was a Confederate flag. The effigy’s crudely painted eyes stared out at Baxter Hall, the residence hall of James Meredith, the man the effigy was meant to represent.

The effigy was the third to appear on campus in as many weeks. The first appeared back on September 13, 1962, even before Meredith had enrolled in his state’s public university as its first African American student. His classmates strung up the second effigy on October 2, one day before the third effigy was hanged. The sign draped around this second figure informed Meredith, “We’re gonna miss you when you’re gone,” and in the middle of the night, a crowd of students gathered outside Vardaman Hall to set the effigy aflame and shoot off firecrackers to intimidate Meredith with the sound of the explosions.

The similarities between the effigies of James Meredith and the thousands of black bodies hanged and burned by southern lynch mobs over the years were intentional. Just as their parents and grandparents had used ritualized violence against black bodies to celebrate white supremacy, the University of Mississippi students who displayed and burned these effigies performed a ritual desecration of Meredith’s body. The bodies left hanging around campus may have been filled with cotton, not the flesh and blood of African Americans, but these effigies proudly invoked a tradition of lynching that reaffirmed the same culture of white supremacy that lynching had celebrated for over one hundred years.

To say that these effigies were merely representations of violence would ignore the reality that these were far from empty threats. Meredith’s “welcome” to the campus began with a violent riot put down by thousands of U.S. marshals that left two people dead and hundreds of marshals and rioters injured. For the remainder of the academic year, armed marshals accompanied Meredith almost everywhere he went to protect him from physical violence, though they could do little about the verbal barbs and epithets hurled his way almost daily. In the weeks and months that followed, Meredith received hundreds of death threats. A letter from Troy, Alabama signed “The Sovereign States of Alabama and Georgia” made a sorry attempt at poetry, practically shouting through the page in all uppercase letters:

ROSES ARE RED

VIOLETS ARE BLUE

I KILLED ONE NEGRO

I MAY MAKE IT TWO.

The subsequent stanzas threatened to castrate then hang Meredith and his “friends” if they ever set foot in Alabama or Georgia—his friends presumably being Martin Luther King, Jr., Medgar Evers, and Robert Kennedy. A letter signed simply “Buddy” predicted that someone would “pinch [his] head off” and make his wife a “black widow.” Others entertained fantasies about his death by lynching, like one postcard that read:

Dear Nigger bastard, I hope they hang your black ass from the biggest tree around. You fucking aborigini [sic] prick. You eight ball cocksucker. You prick cannibal. Your [sic] a mother-fucker you black fuck. Love, The Whites

These letters, and dozens if not hundreds of others like them, not only threatened Meredith’s life but did so by pointedly deploying the rhetoric of lynching. That letter from Alabama made a direct allusion to one common feature of lynching, the mutilation and castration of male victims. Descriptions of Meredith’s body hanging from a tree evoked the spectacle of lynching: the carnivalesque atmosphere of the ritual, the souvenir photographs sold afterwards, the display of the body for passersby to gawk at. These letters also spewed racial epithets that, like lynchings themselves, unequivocally illustrated that these warnings were directed not only at Meredith but at the African American community more generally.

Most of these threats arrived as letters and telegrams, but his fellow students hurled more than taunts and jeers at him—they also threw rocks, bottles, cherry bombs, and firecrackers. One day Meredith even found a dead raccoon on the hood of his car. Within a matter of weeks, the dead bodies had piled up, though, thanks in part to the marshals, Meredith’s was not among them. The list included three effigies, the remains of Paul Leslie Guihard and Ray Gunter who were killed in the riot, the dead raccoon, and the figurative corpse of Meredith imagined in a growing stack of death threats sitting on his dorm room desk. A couple weeks prior to Meredith’s enrollment, a white undertaker from Corinth, Mississippi named Bill McPeters even sent a telegram offering to take the corpses of Meredith and any other “troublemakers” off Governor Ross Barnett’s hands and to bury them free of charge. What might have seemed like rhetorical chest-thumping had some substance to it. In his telegram, McPeters boasted about “own[ing] the ground that the tree still stands on that was used about 55 years ago: when one got out of place.” The lynching the undertaker referenced had occurred well before he was even born, but he used the force and power of that lynching to lend credibility to his offer. Meredith was spared bodily harm and McPeters’s services weren’t necessary, but the students who repeatedly hanged these effigies intended these representations of lynching to have the same practical effect as lynching itself. They hoped to intimidate Meredith into dropping out of the university so that their “southern way of life” (i.e. white supremacy) could continue unchallenged.

Meredith remained remarkably unflappable despite the daily onslaught of verbal and physical threats. When a reporter asked what he would like to say to his classmates, he answered, “I’ve noticed that a number of students looked like they’re mad. I don’t know what they’re mad at, but if they’re mad at me, I’d like to know about what.” He gave measured responses to reporters’ questions about the violence and vitriol, the isolation and insults, but after his 71-year-old father was awoken in the dead of night by shotgun blasts fired into his house, he wondered how much harassment he could stand to put his family through. In an article he wrote for the April 19, 1963, issue of Look, he lamented that “hearts have now shown that they don’t intend to change,” but he also vowed to continue his fight for racial justice, despite his trepidations about threats to his family. Meredith made only passing reference to the threats directed at him, which he derided as undignified and shameful. What must have been an unnerving barrage of verbal and physical attacks to endure, he largely brushed off as more evidence of his home state’s well-deserved reputation for racial vitriol.

Americans, especially white southerners, have a tendency to ignore or silence the more disturbing elements of the South’s fraught racial history. In light of these tendencies, I bring to my writing a commitment to unearth what are often painful, ugly stories and to narrate them in ways that affirm the humanity of lynching victims, their families, and their communities. I see the recovery of these stories and images as an elegy of sorts for the victims and survivors of lynching, an elegy that so often has been confined to hushed conversations among family and friends or trapped in the subconscious memories of survivors.

Writing thoughtfully about extreme violence and responsibly using images depicting that extreme violence matters, especially because I so emphatically want to avoid reinscribing the very objectification of black bodies that I hope to combat through my work. Lynch mobs actively tried to transform people into objects (and object lessons) by pairing the public spectacle of these extralegal killings with the extended torture and grisly mutilation of black bodies. Likewise, lynching postcards that showed smiling white faces posing with dead bodies were reminiscent of the photographs that hunters took with their trophies after a successful kill. Effigies quite literally objectified the people they represented by dispensing with once-living bodies, which, in part, is why this subject presents particular challenges for humanizing the experiences of those targeted by the effigies.

I have linked to only one image of an effigy here. I could have included several more, but I imagined my readers scrolling through slide after disturbing slide of symbolic death, losing track of which stuffed figure represented which flesh-and-blood person. I worried that, after the first few images, readers might reach their capacity for processing this onslaught of violence. They might gaze at each subsequent image in a way that unwittingly would risk anonymizing and objectifying the people depicted by those effigies, which would be an insult to their memory. To forego images altogether would seem to replicate the erasure of lynching from public consciousness, so I chose one image: a photograph taken on October 3, 1962, of James Meredith in effigy. Although the question of how to represent lynching is always up for debate, I hope I have, for the time being, settled on a respectful and ethically defensible position that best serves the elegy I am writing.

The number of lynchings declined significantly by the time the United States entered World War II, but effigies like the ones left hanging on the grounds of the University of Mississippi cropped up all across the South in the decades that followed. Even before the war, back in 1939, the Ku Klux Klan hanged a black effigy from a telephone pole in Miami, Florida to intimidate African Americans who had registered to vote. The bloodstain that spread from the effigy’s heart and ran down its torso onto its legs was partly covered by a sign announcing, “THIS NIGGER VOTED.” Three decades later, in 1965, dead black crows with nooses around their necks hanged from the limbs of the grand oak trees lining the road just outside Tchula, Mississippi. African Americans driving to the county seat knew those crows swinging from the tree limbs were meant for them to see, even without a sign telling them what would happen if they registered to vote.

These effigies and numerous others explode the comforting (not to mention ahistorical) myth that the moral fiber of humanity inevitably improves with the march of time. As recently as February 16, 2014, three white fraternity brothers at the University of Mississippi allegedly vandalized the statue of James Meredith that stands between the university’s library and the Lyceum, where the 1962 riot had been concentrated. Early that morning, a contractor noticed the vandalized statue with an older version of the Georgia state flag—one that prominently featured the Confederate battle flag—draped over its shoulders and a noose tightened around its neck. The full monument depicts Meredith walking through a door labeled “courage,” “knowledge,” “opportunity,” and “perseverance,” and though the perseverance referenced on the door celebrates Meredith’s unflagging persistence in his fight for racial justice in Mississippi, the perseverance of a white supremacist element on that campus exposes the bitter irony of the monument.

This is not to say that the racial status quo is forever stagnated or that these racist images are impossible to dislodge. Depending on the findings of the ongoing criminal investigation, these students may be charged with a hate crime, and the investigation itself is evidence of a significant shift in social tolerance for lynching since 1962, much less since 1891 or 1908 or 1935 when actual lynchings occurred in Oxford, Mississippi but went unpunished. But what makes the repetition of the symbolic lynching of James Meredith so troubling comes to the fore when we remember that you don’t need a flesh-and-blood body dangling from the end of a noose to realize that these representations, and the racist sentiments behind these representations, carry with them a standing threat to the African American students and residents living in Oxford, Mississippi.

Dedicated on October 1, 2006, this monument on the University of Mississippi campus commemorates the integration of the university with a statue of James Meredith walking through the doorway of courage, knowledge, opportunity, and perseverance. Just a few hundred yards away is an enormous monument to Confederate soldiers. December 7, 2011. Mari N. Crabtree

I have struggled to figure out how to write an elegy for a living person and how to write an elegy for a practice that persists today. An elegy implies a kind of finality or closure, but the issue of racial violence seems far from resolved in places like Oxford, Mississippi. Nevertheless, the impulse to remember and the imperative to humanize these effigies remain at the core of my work. I remain cautiously hopeful though—after all one needs at least a sliver of hope when writing about lynching and effigies. I hope that recovering how and why white southerners have deployed the rhetoric and imagery of lynching will prevent fresh bodies from appearing so we can properly eulogize the ones that have come before.