A Pirate Surgeon in Panama

A photo taken from a dugout canoe in the San Blas islands, where Lionel Wafer returned to his English crewmates after being adopted into a Kuna Indian tribe. Olosipu via Wikimedia Commons

The ship came to anchor on an August evening. Sea fireflies glowed around the moorings, their indigo light making specters of the sailors’ gaunt faces. There had already been two mutinies, and the nerves of the crew were as frayed as the ship’s ropes.

At dawn the next morning, the captain fired two cannons to signal that it was time for the Kuna Indians to return their guests—or their hostages, depending on your point of view. Long dugout canoes glided toward the ship from the beach. At length, four bedraggled figures were hauled onto the deck: crewmembers who had been left behind in the spring. But a fifth, “painted like an Indian” and wearing a loincloth, stayed apart. “He was some time aboard before I knew him,” remembered his closest friend, the captain.

The fifth man left his own account. “I sat awhile cringing upon my hams among the Indians, after their Fashion, painted as they were, and all naked” he recalled. His face was partially obscured since “my nose-piece [was] hanging over my mouth.” It took almost an hour for his shipmates to recognize him. Then one started backwards in shock. “Why! Here’s our doctor!” the man cried, and a crowd gathered around him, trying to rub off the geometric paint that obscured his features.

It was Lionel Wafer, the pirate surgeon.

Almost everything we know about Dr. Lionel Wafer comes from his own pen. He enters the historical record as a teenage surgeon’s apprentice who risked the hazardous voyage to the Indian Ocean on an East India Company merchant ship in the 1660s. He surfaced next in Jamaica. The island, at that time a new possession of the British crown, was beginning to acquire a reputation as a place where working-class Britons could make their fortune—largely via the brutal exploitation of enslaved African sugar plantation laborers. Wafer found work as a plantation surgeon, tending to crushed limbs, malarial fevers, venereal diseases, and other dangers of colonial life.

But the 1670s was also the golden age of piracy, and pirates always needed surgeons. Wafer, evidently feeling wanderlust, joined an expedition in 1679. A year later, we find him among the crew of the notorious buccaneer Bartholomew Sharp on a voyage to pillage the rich ports of the Spanish American Pacific coast (the “South Seas” of pirate lore). It was there that he became close friends with William Dampier, who emerged as the expedition’s leader.

And it was on an expedition with William Dampier in the isthmus of Darien, on the Atlantic coast of present-day Panama, that Wafer’s troubles began.

The word “buccaneer” was a reference to the makeshift eating habits of early European settlers in the Caribbean, having been adapted from the French boucan, “a frame on which to cook meat,” originally from the native Tupí languages of Amazonia and the Antilles. The motif is still visible in this 1707 map of the South Seas showing the early English navigator Thomas Cavendish enjoying a proto-barbeque with his crew. Pieter van der Aa, “Zee-togten door Thomas Candys na de West Indien.” copperplate map, 1707 (Wikimedia Commons)

Three years ago, I visited the Rare Books and Manuscripts Room at the British Library to read Dampier’s manuscript account of his voyages. Throughout his text, Dampier refers to Wafer simply as “our chirurgeon [surgeon].” One day in the jungle, Dampier writes,

our chirurgeon came to a sad disaster. [While] drying his powder a carelesse man passed by with his pipe lighted and sett fire to his powder which scalded his knee and reduced him to that condition that he was not able to march, wherefore wee allowed him a slave to carry his things being all of us much dissatisfied at the accident.

With his knee “scorch’d” so badly “that the Bone was left bare, the Flesh being torn away,” it soon became apparent that Wafer was going nowhere. Almost immediately, according to Wafer’s account, the “Negro whom the Company had allow’d me for my particular Attendant, to carry my Medicines” absconded into the jungle. (I wish we could follow this unnamed man’s journey into the jungle, but unfortunately his disappearance in the undergrowth mirrors his disappearance from the historical record.)

Unable to travel and without his medicines, Wafer parted from the rest of the company. He stayed behind in the Darien with a crewmember named Richard Gopson, former apprentice druggist in London and “an ingenious Man, and a good Scholar,” in Wafer’s estimation. “The Indians undertook to cure me; and apply’d to my Knee some Herbs,” Wafer reported, applying a poultice for twenty days that left him “perfectly cured.” Before long he’d gained fluency in the local Kuna dialect, making observations about Central American medical and bodily practices in the process.

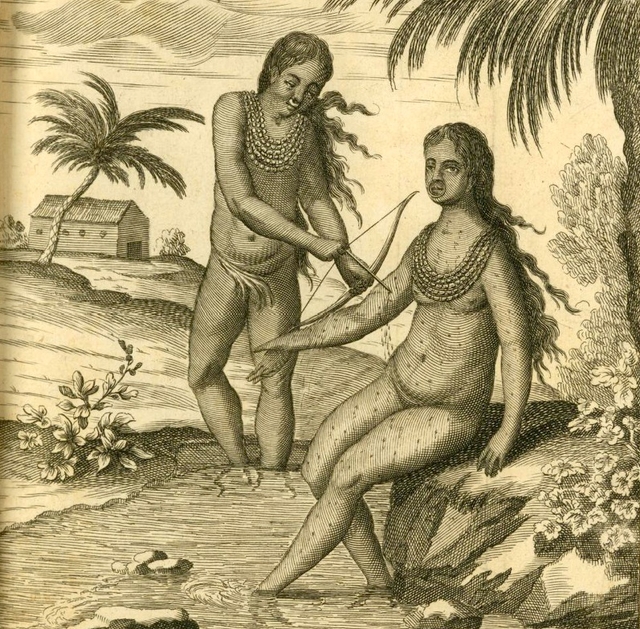

A depiction of Wafer’s patron, Lacenta, along with his wife, children and attendants, from Wafer’s New Voyage and Description (London, 1699). “I went naked as the Salvages,” Wafer remembered, “and was painted by their Women; but I would not suffer them to prick my Skin, to rub the Paint in.” Internet Archive

In one memorable episode, Wafer participated in a medicinal ‘bleeding’ of the wife of the local Kuna leader, Lacenta. Wafer’s own account of the incident portrays him as a heroic ‘civilized’ physician who was able to convince the Indian medical practitioners that the European style of medicinal bleeding (phlebotomy) was far superior:

It soe happened that the day after our arrival at the Kings Pallace one of his Queens being indisposed was to be lett blood which their Drs. thus performe[:] The Patient is seated on a Stone in the River and the Doctors with a small bow shoot their arrowes into the naked body of the Patient from head to foote shooting their arrowes as fast as they can not missing any part[.] [B]ut the arrows are gaged soe that they penetrate noe further then wee generally thrust our Lancetts and if they hitt a veine which is fulle of winde and blood spurt out a little they will leape and skip about shewing many antick gestures in triumph of soe great a piece of Arte…

The result was a bizarre battle between competing approaches to phlebotomy. For Wafer, as for other early modern physicians, the body was a microcosm of vital humors that it was the physician’s job to keep in balance. Diet and medicines could do part of the work, but when symptoms became dire, harmful humors had to be forcibly evacuated from the body, and bloodletting was the preferred way to achieve a balance.

Wafer failed to acknowledge the obvious parallels between his own medical techniques and those of the Kuna healers, who also practiced extensive bloodletting. Instead, he portrayed himself as an enlightened purveyor of modern medical techniques to a backward culture: “Perceiving their Ignorance,” Wafer wrote, he “told the King that if he pleased I would shew him a better way without putting the Patient to Soe much torments.” The king gave the word, “and at his Comand I bound up her Arme with a piece of Barke and with my Lancett breached a veine.”

The Kuna practice of bloodletting, as depicted by John Savage, the engraver for Wafer’s 1699 book. Internet Archive

Despite Wafer’s confident belief in European medical superiority on this occasion, other parts of his account hint that he embraced indigenous American culture and practices. Although Wafer himself minimized this acceptance, Dampier’s parallel account makes it clear that Wafer fully adopted the bodily aesthetics of the Kuna, appearing “painted like an Indian,” complete with a large golden nose ring. In his account Wafer played down his adoption of Kuna customs, but there’s a perceptible wistfulness in his remembrance of his time in the Darien. Back in England, Wafer was a commoner with no medical license and no social status. But among the Kuna, he “was carried from plantation to plantation and lived in great Splendor and repute.”

Although Lionel Wafer’s story is largely forgotten today, it offers a fascinating parallel with the far more famous “captivity narratives” of Puritan New Englanders who lived among Algonquian tribes in precisely the same period (you can read Glenda Goodman’s account of one of the most famous in a previous Appendix article). Like North American captives, Wafer was formally adopted into a Kuna community and declared a “son” of King Lacenta. He learned the Kuna language, traveled in a royal hunting party, and gained knowledge of local plants and medicines.

“A boy lights one end of a [tobacco] Roll,” Wafer recalled, “the End so lighted he puts into his Mouth, and blows the Smoak through the whole length of the Roll into the Face of every one of the Company or Council, tho’ there be 2 or 300 of them.” Internet Archive

But if Wafer is far from the only seventeenth-century European to leave a report of his adoption into an Indian tribe, there are aspects of his story that are virtually unique. As we’ve seen, he practiced a form of hybrid Kuna-European medicine. He also left a curious report of what he called the “Moon-ey’d” Kuna, with “Milk-white skins … much like that of a white Horse,” and crescent-shaped eyes. They were “dull and restive in the Day-time, yet when Moon-shiny nights come, they are all Life and Activity … running as fast by Moon-light, even in the Gloom and Shade of the Woods, as the other Indians by Day.” This strange account reflects a well-documented propensity toward albinism among the Kuna—but for Wafer, it was further proof of the supernatural nature of the Panamanian jungles.

While with the Kuna, Wafer also witnessed the work of shamans (Pawawers or conjurors, as Europeans called them) who predicted the circumstances of his return to the Christian world with uncanny accuracy. They had done so, Wafer claimed, by summoning the devil:

They sent for one of their Conjurers, who immediately went to work to raise the Devil, to enquire of him at what time a Ship would arrive here; for they are very expert and skillful in their sort of Diabolical Conjurations … They continued some time at the Exercise, and we could hear them make most hideous Yellings and Shrieks; imitating the Voices of all their kind of Birds and Beasts.

The pawawers declared that Wafer would be rescued in ten days, but that his companion Gopson would die soon after: “All of which fell out exactly according to the Prediction.” Wafer’s account of the devil in the New World was to be expected–Spanish and Portuguese chronicles of American conquest described indigenous Americans who wielded the power of Satan to prognosticate, curse, or cure.

Tupi Indians in Brazil tormented by devils (detail). Theodor de Bry, Americae tertia pars (Frankfurt, 1592), 223. John Carter Brown Library

Yet because it portrayed these “Diabolical Conjurations” as accurate, Wafer’s account raised unsettling questions about the potentially supernatural origin of travelers’ knowledge during an era when such knowledge had never been more valuable. As David Livingstone, Harold Cook, and other historians have shown, travelers’ accounts provided the first-hand reporting of phenomena that fueled the development of the natural sciences. But who was an acceptable source for this data? Could it come from shamans as well as surgeons?

By the close of the seventeenth century, what Anna Neil has called ‘buccaneer ethnographers’ like Dampier had demonstrated that even criminals and pirates could collect empirical data about the world’s ethnography and geography. Yet the personal histories of such individuals, who frequently resided among non-Christian indigenous peoples for extended periods, put them in the complex position of serving as mediators between scientific travel and indigenous spirituality.

Wafer’s adoption of Kuna dress and ceremonial body paint, in particular, raised concerns about his trustworthiness that were tied to larger debates about the role of the devil in society. John Bulwer’s 1656 frontispiece to Anthropometamorphosis, or the Artificial Changeling, for instance, shows a European woman, a hair-covered man and a South American Indian with full body paint standing side by side. They are being judged by Nature, Adam and Eve and a body of disapproving magistrates (including the ghost of Galen) for transforming their bodies, while the devil flies above them laughing and saying, “In the image of God created he them! But I have new-molded them to my likeness.”

Europeans and indigenous Americans being judged at the court of Nature for modifying their bodies, from the frontispiece to John Bulwer’s Anthropometamorphosis (London, 1656). Wikimedia Commons

Wafer had written that his Kuna body paint eventually rubbed off, often with the “peeling off of Skin and all,” to reveal a European underneath–but did his time in the world of the Kuna leave traces of the indigenous that took longer to disappear? (Mairin Odle has written previously for The Appendix about the difficulties of removing early modern tattoos).

As a pirate surgeon, Wafer stood squarely in between these two worlds. As Britain’s preeminent firsthand witness of the Panama region, he was a key figure in early attempts to understand the American tropics—and in efforts to make use of its resources. Indeed, in July of 1687 Wafer had been interviewed regarding the Darien’s colonization potential by none other than John Locke. Wafer’s account had also been printed and bound together with an account of Darien written by an unspecified “member of the Royal Society” in the same year.

In the preface to the second edition to the New Voyage and Description, printed in 1704, Wafer attempted to reaffirm his status as a credible observer, writing that he wished to “vindicat[e] my self to the World” regarding his previous account of “the Indian way of Conjuring,” which, he explained vaguely, had “very much startled … several of the most eminent Men of the Nation.” In this preface Wafer continued to maintain that the Kuna shamans practiced Satanism, and he buttressed his authority by citing parallel accounts produced by Scottish settlers in the Darién. He pointedly refrained, however, from defending his earlier claims about the accurate predictions this method produced.

Would Wafer have affirmed the truth of “diabolical conjurations” if he were in Europe and not Panama? Or did these powers exist only in relation to the spaces that harbored them? Was the devil different in the tropics, and among tropical bodies? The story of Lionel Wafer, the pirate surgeon of Panama, leaves the question open.