Mozart’s Skull: the Hyrtl Skull Collection at the College of Physicians of Philadelphia

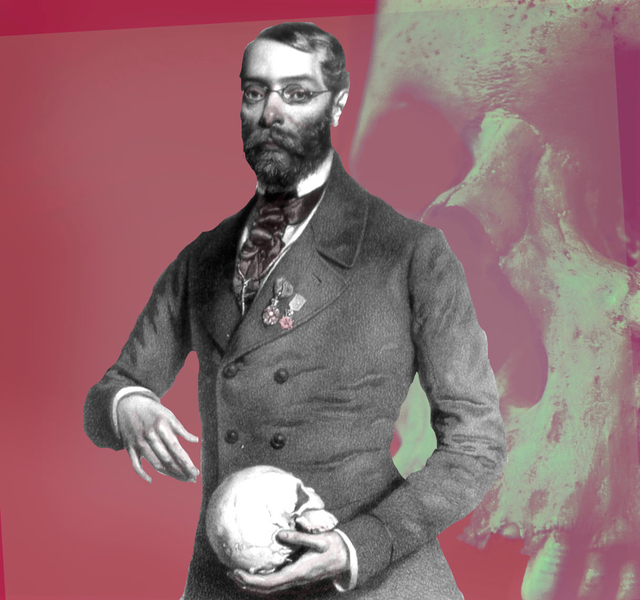

Joseph Hyrtl was proud of his hearing organs, and would not sell them cheap.

In 1866, the Viennese anatomist explained to the College of Physicians of Philadelphia that his collection of human and animal auditory bones could not be separated from each other. If Philadelphia wanted his collection—“the pride and ornament of my private museum since the English, in the exhibition of 1862, styled it admirable”—the college would have to pay $7000, or about $104,000 today, for the surround sound experience, as it were. “The fishes and reptiles of the same catalogue are also to be disposed of,” he added.

In 1874, the College talked the price down to about $4,800, and pulled in a lot more besides, including 139 human skulls that Hyrtl had used to try and debunk phrenology, the pseudoscience that theorized that a skull’s shape, size and bumps reflected the character of the mind—and the person—it protected. Today, a wall of those skulls stare down at visitors to the College’s Mütter Museum, Philadelphia’s most Appendix-y of destinations, overflowing with gruesomely human and humanly gruesome preparations of human skeletal and internal organs, including slices of Einstein’s brain. The collection is justly famous, but it takes some upkeep: last winter, the hot gift online—in some circles, at least—was a skull “adopted” from the Hyrtl wall; prospective “parents” paid $200 for a skull’s restoration and remounting.

The story of skull collecting in the nineteenth century is a dark one, rippling with scientific racism and the disquieting means by which many skulls were gathered—even in a collection built to debunk bad science. Many of the Hyrtl skulls, for example, belonged to people who died at a disadvantage: at their own hands, or those of the state, or in jails or poorhouses. Hyrtl also didn’t mind employing a resurrectionist (grave robber) or two.

But before we judge, it’s best to read the evidence for ourselves. For this issue of The Appendix, ‘Bodies,’ we reached out to our friends at the College, and Annie Brogan, the College’s Librarian, reached into their archives for the letters that brought Hyrtl’s collection to Pennsylvania’s capital. It makes for occasionally banal reading—a collection is a collection, and that means haggling—but there are flashes of the humanity beneath: preparations of placentas and organs injected with tinctures, humans working to ready human tissue for microscopic study.

Still more compelling is the catalogue of the collection, which we’re also proud to share. Tableaux of the skeletons of crocodiles, breaking their shells, jostle with preparations of six “well mounted” genital organs, showing “the blood vessels of the uterus & Vagina, with Ovary, in pregnancy, […] the vascular structure of the penis (splendid),” etc.

And of course, the seventy “perfect, snowy-white” skulls of “all the tribes of Eastern Europe,” some of them accused murderers. “It is easier to get the skulls of Islanders of the Pacific,” Hyrtl wrote, “than those of Moslim, Jews, and all the semisavage tribes of the Balkan & Karpathian [sic] valleys. Risking his life, the gravestealer must be largely bribed. My pupils who are physicians to Turkish Pachas [sic], procured most of them for me.”

There is as much inadvertent history in these brief accountings—of power, science, racism, gender, and culture—as there are in whole books.

But, lest it all be grim, there was also what may have been the “Skull of Mozart,” which Hyrtl claimed was “Authentic, without maxilla inferior.” Mozart’s hometown of Salzburg offered Hyrtl 200 Thalers for it; Hyrtl wanted 300. It wasn’t among the haul that reached the Mütter Museum, though. Mozart’s skull is, unsurprisingly, hard to “score.”

Here is Hyrtl’s letter on the subject:

Vienna, Oct. 29th. 873

Honoured Sir,

In reference to your letter, dated Oct. 7th, I hasten to give the following information.

1) The enclosed list contains my anatom. Preparations, which I can dispose of presently. Many of them were exposed in the Vienna exposition, as chosen objects of my private anat. Collection. They are perfect in every respect.

2) The letters A, B, C, of the list, denote three small treatises, which will come to your hands with this letter, and which contain a short explanation of the preparations. The collection of skulls is not contained in them because the skulls were exposed towards the end of the Exhibition, on demand of the Committee.

3) Each tableau of the organs of hearing (I & II) has been augmented of 5 numbers of great rarities (gorilla, embryo of elephant, otaria, mysticetus, bison, etc.). The small boxes III, IV, V, and VI, mentioned in C pag. 37, contain such objects which are partly already contained in the Tableaux I [page torn] partly are of a common kind. [Page torn] made presents of them to renowned brother-anatomists who visited my Exposition. The labyrinths of birds are so similar to each other, that the last preparation in Tableau I (Labyrinths of Mammalia), which is of a hawk is sufficient to give an idea of the not varying configuration of the Labyrinth in birds

4) The contents of the list are indeed models of technical anat. Workmanship. The placenta & corrosions, as well as the microscop. Injections /: many of them are things quite new & as beautiful as instructive.

5) I should feel very happy if my anat. treasures, or part of them, should find a hospitable roof in a great scientific establishment, instead of being dispersed in various Universities. The prizes [sic] in correspondence to the value of the objects.

If you will give orders, they shall be strictly executed by,

Your obedient servant

Prof. II Jos. Hyrtl