CSI Buenos Aires: The Crime on Prudan Street

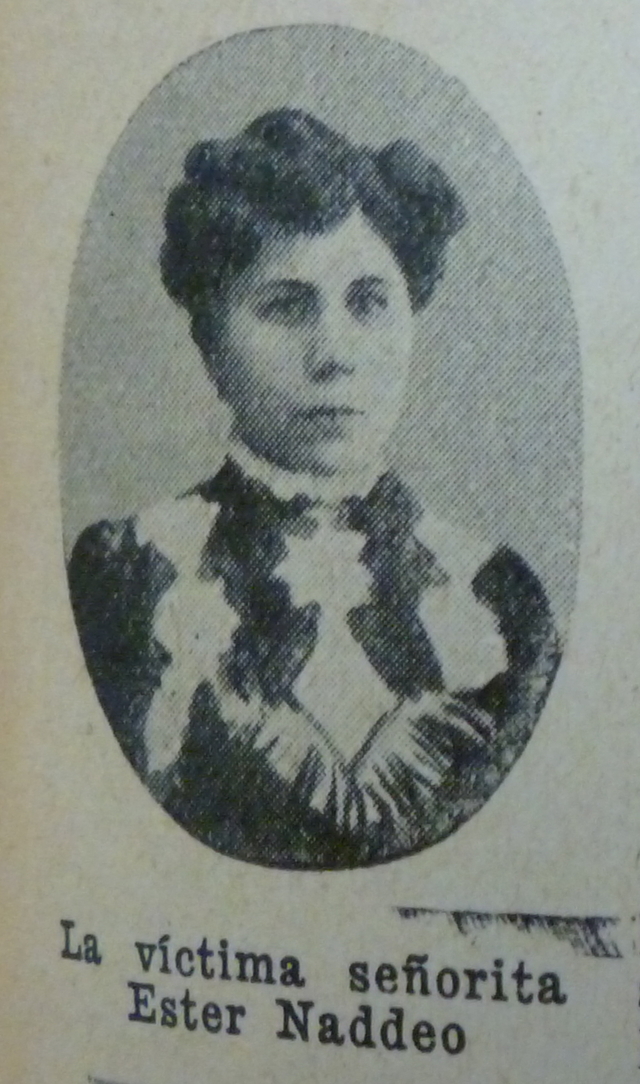

Ester Naddeo was dead. She had been living at 127 Calle Prudan in Buenos Aires for about four months. But on Sunday, the ninth of January, 1910, her corpse was removed from the apartment by police. She was just 33 years old.

In the following days the incident would simply be referred to as “El Crimen de la Calle Prudan.” It is evident from its title that this incident was public knowledge, an ephemeral shorthand. One could utter these words in early 1910 Buenos Aires and listeners would know exactly what was being discussed. And yet, there was nothing particularly interesting about the case, at least nothing extraordinary. Instead, it was the seemingly ordinary way in which the story was reported that warrants our attention. “The Crime on Prudan Street” is one of many headlines from that era that reveal a deeper history of popular interest in crime dramas, one that feels very familiar today.

I sat one night re-reading and transcribing newspaper reports on the incident after a day in the archives in Ushuaia, Argentina (nearly 2,400 kilometers south of the crime scene). While channel surfing to find some appropriate background noise for my night’s work, I noticed that so many of my options were crime shows. From Bones and the CSI series to one of the Sherlock Holmes movies and its small-screen incarnation, Elementary, these dramas aired in English with Spanish subtitles or were dubbed in a neutral Spanish for a diverse group of Latin American audiences. I was amazed at how similar the accounts from my 1910s newspapers were to those that I was watching (or not watching) a century later. The premises, questions, and cliffhangers, my archival photos of mug shots and crime-scenes—they all read like scripts from contemporary Hollywood. These shows, made in the United States and enjoyed in faraway countries like Argentina, were not solely representations of American pop-culture exported abroad, nor were they simply a sign of current Argentine interests—this is a continuation of sorts.

We are all familiar with Sherlock Holmes, one of the first and most treasured products of this era, whose fictional investigations captivated audiences in greater Britain and beyond. Indeed, silent films were already being made of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s character in the 1910s. But while detective innovations such as fingerprinting were being discovered by Englishmen in the colonies and refined by police teams in London at the turn of the century, they were simultaneously being perfected across the Atlantic in Argentina. So too were the proposal and creation of identification cards to be held by immigrants and criminals that included the carrier’s anthropometric and biographical data. Argentina, after all, was one of the world’s epicenters for modern criminology during this era. Embracing these new methods, news outlets as well as popular magazines invited readers along to investigate crimes by tracking and reporting on the operations of this fledgling yet burgeoning field of criminal experts. When La Prensa asked, “Did Arnold murder señorita Naddeo, and were his wife and the mulato his accomplices?” it was not simply a rhetorical question. The police were on the case, and so was the public, reading along in their living rooms, cafes, and trolley cars.

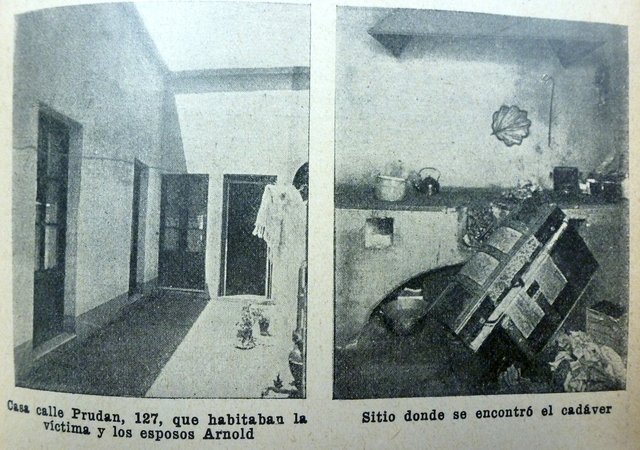

For those following Naddeo’s murder, a scrapbook of cutouts from public sources could start to look as detailed as a police file. Newspapers and magazines provided all of the available information, including a photo of the front façade of 127 Calle Prudan and a blueprint of its interior floor-plan, which numbered the various rooms within the building so that readers could visualize the crime scene and recreate the series of events for themselves. Police released home photographs obtained from the scene, including one of the now departed señorita Naddeo gowned in black and a photo of her next door neighbor, the adolescent Emilia Gurruchaga. Gurruchaga had witnessed a suspicious character exiting the home. “The mulato,” as he was named in these accounts, appeared sallow and poorly dressed. After an interview with Emilia’s father Teófilo, readers learned that one could hear everything that happened next door due to the design of the building.

But what did the neighbors hear?

Around noon on the day of the crime, Arnold’s wife Rosario Cesárea Gómez had encountered Teófilo’s wife Josefina Gurruchaga, who had heard Naddeo screaming, but Gómez assured Gurruchaga that her husband Enrique was tending to the matter. If señora Gurruchaga had known the truth of what had happened, La Prensa noted, the suspects would have been apprehended immediately. Instead, she had been calmed, at least temporarily, though her suspicions lingered. At 4 p.m. Gómez told señora Gurruchaga that Naddeo was away from the home and asked if she could stay with their family for fear of being alone until her husband returned. Around 10 p.m. that evening Gómez left the Gurruchaga’s home with “the mulato,” and in the middle of the night, unable to sleep and with no sign of Naddeo, señora Gurruchaga contacted the police.

Precinct 20a, now located under the Avenida 25 de Mayo overpass, began investigations immediately. Police passed through each room of Naddeo’s building. When they approached her kitchen they found the key was still in the lock. Inside they encountered semi-prepped vegetables and other ingredients abandoned on the stove. Naddeo’s body lay there in a dorsal position, her head under the stove and her legs half-covered by a trunk of clothing that had been placed atop the young victim. Officers assessed that Naddeo had been surprised, attacked from behind while preparing lunch. She had been strangled with a kitchen towel that was left tied around her neck. Her face showed scars and strain, the coroner later noted, evidence that she had struggled in the moments leading to her death—her moments of dying. Naddeo’s room had been ransacked, clothing and other items tossed about. All her valuables seemed to be missing. On the bed lay bank receipts and checks.

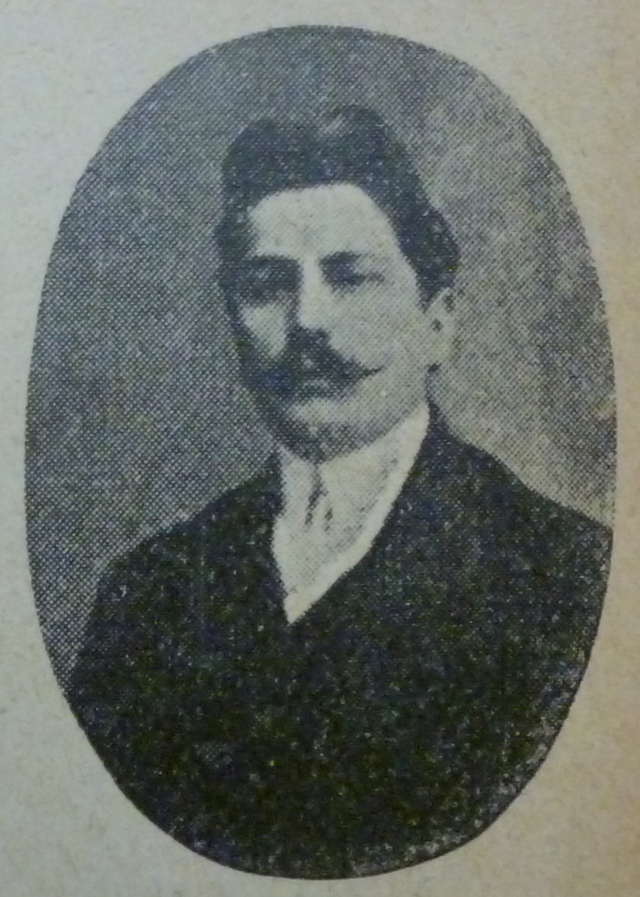

This was a robbery and homicide, but were both premeditated or did one hastily follow the other? Publications posed such questions to their readers as they introduced the primary suspect: Enrique V. Arnold.

Police quickly moved to Arnold’s kitchen where they found two plates of rice soup, bread, and an empty bottle of Italian wine. They traced that afternoon’s timeline and discovered that the wine had been purchased at a nearby shop after neighbors had already heard screams. It seemed that a hurried yet casual lunch had been consumed after the incident. This act proved sensational, interpreted by investigators as a display of the cold blood of the murderers. Or perhaps, this was some twisted fantasy that required unraveling. Arnold and Naddeo’s relationship, readers learned, had begun much earlier at 118 Culpina Flores where Arnold was living at the time. Later, Naddeo came under the care of Arnold and his wife Rosario, and the two women started to playfully call themselves cousins. Arnold and Naddeo soon engaged in a secret romantic relationship, during which time he learned of her large financial resources. She was a property owner and had family to the southeast in La Plata.

While the first police sweep suggested that all valuables had been lifted from Naddeo’s home, still present when they found her body were a pair of gold earrings and an imitation pearl necklace. Investigators also noted that many items found in Arnold’s home appeared to have been there before the crime and were acquired with the knowledge and consent of Naddeo. One photo was even signed with affection from Naddeo to her suspected murderer. As the plot thickened, potential motives leapt off each day’s freshly printed pages. But where was the primary suspect, Naddeo’s married lover? Papers published a photo of a well-dressed and mustachioed Arnold, putting the public on lookout.

Arnold was spotted the morning after the murder at the local barbershop, but he was not apprehended. Upon exiting, he asked some kids on the street what they had heard about the incident. He quickly went to a friend’s home to collect his thoughts after learning that a suspect had been identified. From there Arnold checked into a hotel across from the downtown Retiro train station where he acquired some generic laborer’s clothing, further trimmed down his mustache, covered his hands and face with grease, then took the train south to Lanus, just outside of Buenos Aires. Meanwhile, at 5:30 a.m. on the eleventh, two days after the incident, Arnold’s wife Rosario appeared unexpectedly at the investigation office where she was promptly interrogated. She had just twenty cents to her name after having been abandoned by Arnold.

Two days after her interrogation policed detained the wanted accomplice “el mulato misterioso,” Victor Svarna, who also went by the aliases Guardado and Deseado. Svarna was twenty-five years old and had emigrated from Peru to Argentina, where he moved to the outskirts of Buenos Aires. According to police he displayed the typical traits of a child from the slums—cunning and shameless. Svarna was captured in Montevideo, Uruguay, where police had been informed of the crime and provided with photos of the suspects from the precincts in Buenos Aires. The arrest revealed a new clue: Svarna’s as of yet unknown link to Arnold. The two had been shipmates in Montevideo. Svarna wore the evidence on his maritime-themed tattooed sleeves. He had fled Argentina to Uruguay after the murder where he was to meet up with Arnold, but penniless and under pursuit, “the mulato” was identified before the two could reunite. With Arnold still missing, the case against Arnold’s wife and Svarna was quickly brought before a judge. Upon hearing the gravity of the scenario and their potential jail sentences for their connection to the murder, Gómez fainted.

With the two accomplices apprehended, readers had more to learn about Arnold, the still missing primary suspect. Less than a week had passed since the murder, and each subsequent day brought details to pique the public’s interest. Arnold, it turns out, had had an earlier run-in with the law for selling stolen carts to a Spanish farmer. A different incident, which until then went unreported, was that of a hunting ship captain who came forward to claim that Arnold and Svarna had participated in a maritime robbery during their prior stint in Montevideo. It appears that Arnold was quite good at covering his tracks, and that is exactly what he planned to do once more. According to Svarna, he and Arnold coordinated a clean-up. They would return to 127 Calle Prudan with a cart of plants, dirty and rearrange the scene, and then haul away any remaining evidence. With Svarna’s capture, the two never followed through on the plan. Despite these revelations, the story turned dormant for three months, as Arnold did well to evade capture. Finally on April 26th in the Pampa Central, the fertile grasslands outside of Buenos Aires, Arnold was apprehended. Comisario Julio Berdera provided press releases to Argentina’s major newspapers, noting that the publication of Arnold’s photo, like that of Svarna’s, had been helpful in locating the suspect.

Arnold had been lying low by cutting alfalfa outside of the capital. He confessed to his crimes quickly according to Berdera’s statement, suggesting that his conscience and paranoia had been getting the best of him. Robbery is one thing, but murder is quite another. Arnold claimed that he and Naddeo had ongoing intimate relations and that his actions had been provoked when she disrespected his honor. Arnold broke quickly, Berdera wrote. Perhaps he was seeking some kind of plea-bargain—the very thought of prison, Arnold had confessed, made him think suicide a better option. Arnold did not take his own life however, and at his trial in September 1911 a judge ruled that Arnold had premeditated the murder. Svarna was sentenced to two years in prison for his role in the robbery and the attempted cover-up of the murder. Arnold was sentenced to twenty-five years in Ushuaia, Argentina’s southern penal colony on the Beagle Channel.

So many of our TV dramas end here. The crime is solved, the perpetrator is brought to justice and put behind bars, the credits roll. As the case of “Calle Prudan” was coming to a close, magazines like PBT ran the newest episodes, like “El Crimen de la calle Anchorena,” displaying more building-fronts, murder weapons, and mug-shots. There had to be a new story to tell, a mystery to be solved; more blood, more bodies.

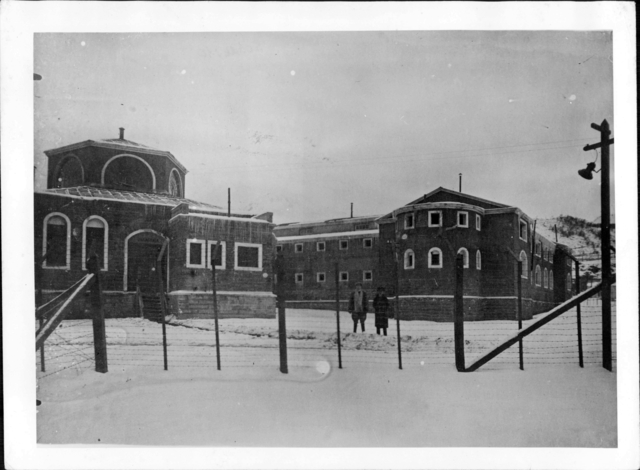

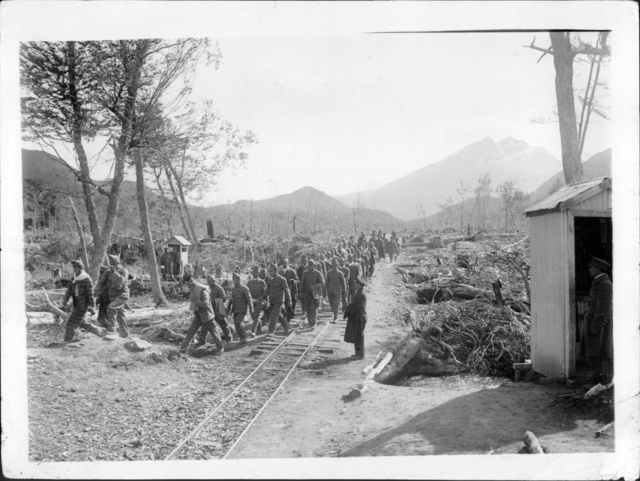

But what happened to Arnold? Though he was terrified of prison life and intent on suicide after his capture, Arnold did not take his own life. Instead, he was locked away in a penitentiary, but not the national penitentiary in Buenos Aires. No, Arnold was exiled to the panopticon penal colony in Ushuaia where he and his fellow inmates were closer to Antarctica than the nation’s capital. Commonly referred as la tierra maldita, or “the cursed land,” the term hardly captures the expletives imbedded in its reputation. There, the condemned labored in thin, damp prison garb marked with their new numerical identities: Arnold became Prisoner 165. Exposed to snow, howling winds, and extreme swings in daylight hours and temperatures, many prisoners died felling timber and laying railroad tracks, living out their days under strict prison regimens.

Prisoners built the local railroad line that then took them to the timber fields for felling. Archivo General de la Nación

While many died laboring to build this corner of southernmost Patagonia, some inmates did take their own lives. In Arnold’s case, it is hard to say why he chose to endure prison life despite his greatest fears. He penned a deeply reflective poem while in Ushuaia titled “De Profundis,” though it never mentioned Naddeo, murder, or suicide. Instead Arnold focused more generally on the human conditions of life and death, on the experiences of living and dying. He complicated any clear distinction between prison life and a life of freedom by questioning the fundamentals of being. In his Ushuaia jail cell, Arnold wrote, “I am dead to all, yet continue to exist.” He was “buried alive,” yet questioned if he was the only one. What surfaces in this poem is a deeper buried life, suggesting that there was another passing the day that Arnold killed Naddeo, not just that of a young female victim from the world of the living to the world of the dead.

“Life wants death,” Arnold wrote, but so too does “death want life.” It is here that we engage the often-untold part of the crime story. While Naddeo’s corpse was ripe for investigation, what about Arnold’s body—his flesh, his sweat and laboring muscles, his breaths in and out? What did these actions mean for the living dead, los muertos que caminan?

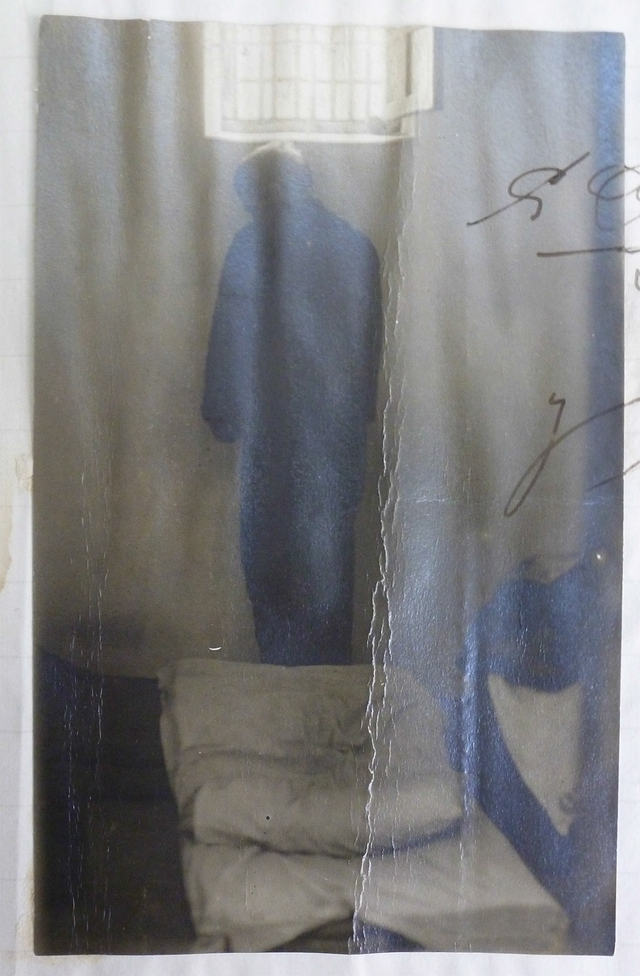

Prisoner 623 was found hanging from his cell window early one morning in September 1920. Museo del Fin del Mundo

Beyond Arnold’s poem, only a few official reports survived—or were ever written—to tell us more of his particular case. These reports would have been beyond the reach of the public, but inmate letters smuggled out of the prison sometimes made it to print. Fellow prisoner Simón Radowitzky, an anarchist exiled for the assassination of Buenos Aires police chief Ramón Falcón in 1909, provided some insight in letters he sent to the federación obrera regional Argentina (FORA). This worker syndicate collaborated with the anarchist publisher La Protesta to circulate these firsthand accounts. Guards labeled Arnold an intellectual subordinate and placed him in solitary confinement in his cell, Radowitzky noted. His rations were limited to bread and water and a perforated metal grate was fixed in place of his glass cell window so as to deny him light yet expose his body to the hissing winds and bitter cold air brought by Antarctic gales and northern glacial gusts. The infirmary doctor claimed that Arnold was on the verge of death after prolonged weeks spent in these conditions. This was in 1921, nearly ten years after his arrival in Ushuaia. Arnold petitioned judges in southern Patagonia with regard to his treatment, but to no avail. He still had fifteen years to serve.

But Arnold did not complete his sentence—he died in the Ushuaia penitentiary three years later, in 1924. His cause of death, unlike Naddeo’s, was not examined in great length, at least not publicly. When prisoners passed away, the official reports did not pad the language of death. Instead, an opening sentence explained how they were found, and all subsequent references to the individual were prefixed with “ex:” ex-preso, ex-recluso, ex-hombre (ex-prisoner, ex-inmate, ex-man). The tortures endured by these prisoners were not revealed to larger audiences until the 1930s, when reporters and prominent political exiles amplified the voice of the “farthest corner” of Argentina—el fin del mundo. Arnold’s cause of death is still not entirely clear, though inmates claimed that he died from tuberculosis induced by his treatment and living conditions in Ushuaia.

Arnold’s poem “De Profundis” on the other hand, rumored to have been found in his cell when guards noticed his corpse, suggests that he had died much, much earlier. Perhaps in Buenos Aires.