Machu Picchu, Revisited

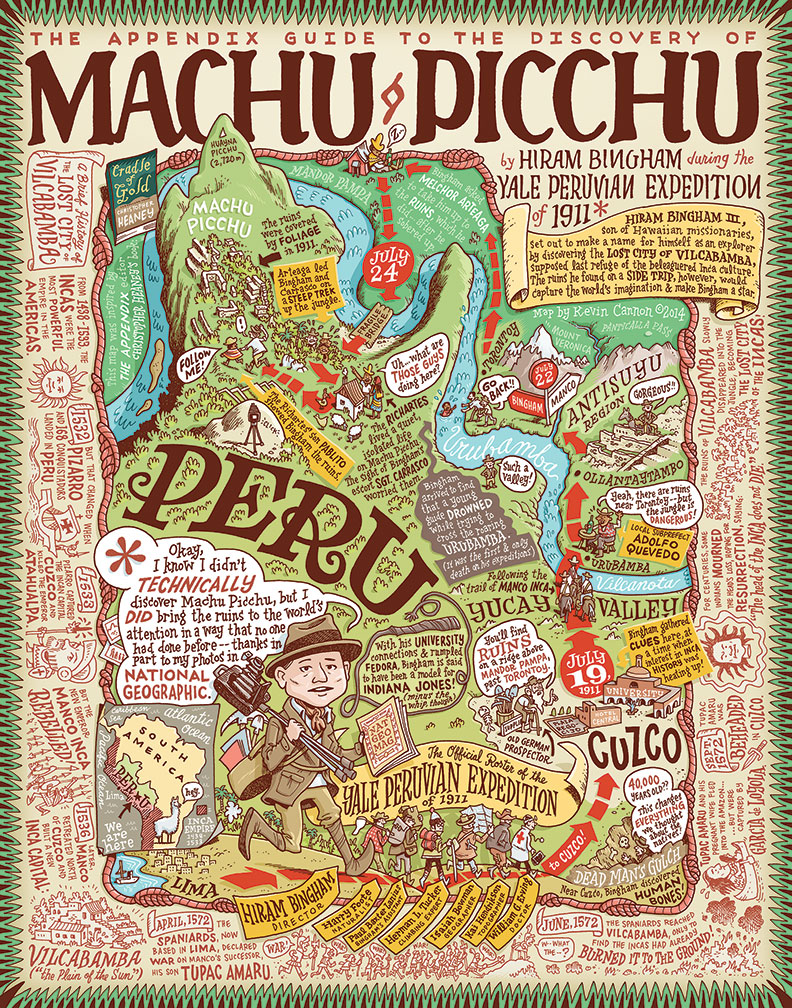

This one’s unique. The last two issues of The Appendix, ‘Off the Map,’ and ‘Digs,’ featured two wonderful and witty cartographic biographies of explorers: Dane Peter Freuchen and half-Inuit Knud Rasmussen, and Gertrude Bell, respectively. Kevin Cannon, a co-founder of the Minneapolis-based cartooning studio Big Time Attic, illustrated both. When we asked him about what explorer he wanted to cover for this issue, ‘Bodies,’ he was very clear: Hiram Bingham, the American historian who made Machu Picchu famous in 1911, and then proceeded to excavate its graves, causing a rather nasty subsequent custody battle between Yale University and Peru.

If you know your Appendix, you’ll know this is a subject near and dear to our heart. One of Kevin’s key sources in drafting his new map, in fact, was a history of Bingham’s expeditions by Appendix co-founder Christopher Heaney, Cradle of Gold. Their conversation over email about the politics of representation of an illustration like this was interesting enough that we thought it might accompany the map’s publication in this issue. For Chris, it was a way to revisit some of the hard choices he made while writing Cradle of Gold. For Kevin, it was a chance to further describe his process in creating for The Appendix. This map is his best yet, we believe, and its back story—while not as compelling as the story of Machu Picchu itself—is nonetheless worth revisiting.

CHRIS So, Kevin, I want to begin by saying how cool I think your new map is, and how much I love the ‘bio-cartographies’ you’ve done for The Appendix. (Have we settled on a name for this new artistic genre you’ve invented?) I especially like how you were able to fit two historical frames on the same map: the story of the conquest of the last city of the Incas, Vilcabamba, and the execution of Tupac Amaru; and the story of how Hiram Bingham reached what he thought was the last city of the Incas, Machu Picchu. There are all sorts of details here I hope we might tease out for Appendix readers in this conversation.

But I want to begin by pulling back the curtain. One of the key sources you used for this map was a book I wrote named Cradle of Gold, a history of Vilcabamba, Hiram Bingham’s discovery of Machu Picchu—with an asterisk, as you so delightfully visualized it—and the subsequent fight over the site’s artifacts between Peru and Yale University, Bingham’s employer. It’s an absolute honor that you were so inspired—but, for reasons I hope we can get into, it’s also a very interesting experience for me. Given all the choices that I know I needed to make in condensing what I gleaned from archives to tell Bingham’s story as a historical narrative, I’m wondering about the choices you decided to make, culling from what you had read.

So maybe let’s start this with a question of process, for you, before we get into the nitty-gritty of what you included, and how that helps me think about what I included, and what those small inclusions mean for how our work is read. How do you go about making these ‘carto-biographies’ (there’s another candidate), and how did you choose, in this specific case on Bingham and Machu Picchu, what you wanted to focus on?

KEVIN

Thanks, Chris. Part of the fun for me in creating these maps is picking a region of the world I know nothing about, and then picking a hyper-specific aspect of that region and learning as much as I can about it. I’ve found that for me to really learn anything—and have it stick—it helps to start learning a region through a particular explorer or an exciting adventure. Seeing Syria through Gertrude Bell’s eyes in the last map, for instance, taught me more about Druze culture and the pre-WWI Turkish/Syrian conflict than if I’d just read a Wikipedia article. Likewise, I couldn’t tell you much (or anything, really) about Peru and Inca culture until I saw them through Hiram Bingham’s adventures. These are biased lenses to see other parts of the world through, no doubt, but they give me a foundation to build on.

For the Peru map specifically, I was really struck by your narrative structure in Cradle of Gold and how you used the image of a khipu to weave together different timelines in Peru’s history. As a reader I was immersed in the fall of the Inca Empire and the adventures of Hiram Bingham simultaneously, and I was determined to have the illustrated map reflect this combining of timelines.

The hardest part about starting a map like this is narrowing down the scope of the story. In all three maps my eyes have been seriously larger than my stomach, so to speak. The Peter Freuchen map was initially intended to be a visual history of his whole life, but that had to be pared down to one simple trek across Greenland. Similarly, the Bell map illustrates only one short leg on her journey across Syria, and this Bingham map shows just a sliver of his 1911 trek. I make these cuts due to the obvious spatial limitations, but also because I think the fun of these maps come from the small anecdotes on a trip. Going back to the macro issue, if these carto-biographies only showed the big headlines, like “Bingham discovers Machu Picchu “ and left out details like Pablito Richarte showing Bingham the ruins, I think the maps would lose a lot of character.

But with a whole book to work with, you can seemingly add every detail you run across, I imagine. How difficult is it for you to craft your story when you don’t have rigid spatial limitations? I.e. to find that balance between explaining everything but also keeping the reader’s attention?

CHRIS ‘Carto-biographies,’ it is!

It’s harder than you might think, because there are spatial limitations, for better or worse. My publisher contracted Cradle of Gold for 100,000 words, footnotes included. I think it came in as about 115,000? Because once you get into it, and you commit to the conceit of, well, a four-hundred-year history with about six of those years told in incredible detail, it’s very easy to get lost in the weeds, which hide all sorts of interesting people and things lost long ago. Case in point, the letter that The Appendix printed last issue from the topographer on Bingham’s third expedition to Machu Picchu, in which he complains, hilariously, of his privileged tentmate. It was the funniest thing I have ever found in the archives, but it simply didn’t fit the tone of the book, and it would have required me to go into depth on these new actors.

I’m reminded of something the author George Saunders wrote in his terrific introduction to an edition of The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, to the effect that there’s the narrative, which is the conveyor belt that moves the story along for the reader, and that there’s the ‘stuff the author loves,’ which the author wants to just keep shoveling onto that conveyor belt as fast as possible but can’t because the belt will get jammed. Writing a long textual narrative is a combination of figuring out at what speed the belt moves, and then how much of what you, the author, loves that the belt can take. Because there’s a point at which you just have to say, ‘I love that, but it doesn’t flow.’ Does that ring true to you?

But before you answer—I think the bigger issue for me is the framing. I felt I had to publish Cradle of Gold in a timely manner: it spoke to an unfolding conflict between Yale and Peru over Machu Picchu’s artifacts, and my research spoke directly to the debate. I could not have gotten Cradle published that way, though, if Bingham wasn’t the central “Indiana Jones “ style figure. I love histories of Machu Picchu in which Bingham is more a tourist than explorer—there are great ones in Spanish—but given that the core archives I was using were his, and the files that I found in government archives centered on what the Peruvian and U.S. governments were trying to do with the problems Bingham caused, it was hard not to write it using him as the ‘protagonist’—even a ‘Lawrence of Arabia’ style protagonist, who, in David Lean’s 1962 biopic, is sympathetic in the first half, then becomes something far more complicated. Besides, there were key questions regarding Bingham’s intentions that hadn’t been answered: did he ever recognize Peru’s sovereignty over its Machu Picchu artifacts? (Yes.)

What I still struggle with, though, is all the things that focusing on Bingham still left out. There is much more to write about the interactions between Machu Picchu’s farmers and the expedition members. The latter measured the former’s skulls—something that will show up in my next project. The issue of race is central in a way that I didn’t fully unpack: what does it mean when Bingham distinguishes or lumps together the Incas and the Quechua-speaking people that guided him to the Incas’ dead? For example, one thing that jarred me about your map was Bingham’s line, in the lower right, “This changes everything we thought about the natives!” ‘Natives’ is a very charged word, but I didn’t ask you to think on changing it, because, well, Bingham was a very privileged white graduate of Yale in the early twentieth century, and that’s exactly the sort of word he’d used. Changing it would have whitewashed the racism of the era. But I did ask you to consider changing a piece of text related to the University of Cusco. Originally you had it reading “Bingham gave a lecture here when interest in Inca History was heating up! “ Which was true, but I worried that there wasn’t enough on the map that pointed to how local Peruvian knowledge of ruins and interest in history shaped Bingham’s expedition. So I asked you to change it to “Students shared clues here, or “Bingham collected clues here…”

All of which is to say, ‘Good lord, how I feel accountable to the dead…’ It limits what I do with what I find. Which raises a wonderfully perennial question to me: What is the point of history, and what is the point of fiction? How do you think of these maps? Are they documentary? A dramatization? Or adaptations? You also create graphic novels that are more straight fiction—how do you make the choices you do in longform? Do you feel accountable to characters like Army Shanks? Or do you feel more accountable to crafting a good narrative? Would you ever consider doing a longform ‘nonfiction’ graphic novel on your own? There’s the excellent work you and Zander have done with Jim Ottaviani—any other projects like that coming?

KEVIN First of all, I read the topographer’s letter that you referred to earlier, and if The Appendix ever gets into the game of developing sitcoms I hope you’ll strongly consider an Odd Couple spin-off featuring the topographer and his lazy roommate.

We’re in the same boat as far as having to leave out interesting historical details because they don’t fit on the conveyor belt, so to speak. I have an added element of restriction, which is an anecdote’s physical relation to another anecdote. For example, part of the reason why I added the Dead Man’s Gulch bit on the map is that it—being a dig that happened south of Cusco—happened to fall in a blank space in my sketch. So while the dig didn’t have a ton to do with the narrative of finding Machu Picchu, I needed to fill that space and it’s an interesting anecdote. As a side note, I was expecting you to come back and suggest different wording for when Bingham uses the term “native”, but now I understand your reasoning for keeping it in. As much as possible I try to create the map through the explorer’s eyes, even if it results in moments that seem racist, or if the map has features that are wrong or out of date (such as using Bingham’s antiquated spelling of “Cuzco”).

I want these maps to be as historical and factual as possible, but I also want people to realize that they are seen through the lenses of two unreliable narrators. The first narrator is me, a non-historian who will make visual and editorial choices based on both personal interest and artistic limitations or marketing purposes. And as much as possible I try to pull the adventures from the explorer’s mouths. The Greenland map, for instance, was taken directly from two different published accounts of the trip, both written by Freuchen himself. I have no doubt that Freuchen is devoted to conveying the truth, but he’s also a natural showman with a keen interest in selling books, so anything he writes—and thus anything that then ends up on my map—should be taken with skepticism. The Gertrude Bell map was a little different in that I was able to read both the published account and transcriptions of her journals written while on the trip. But there again a skeptical reader will question whether she, someone traveling through foreign country in 1905, could ever write a truly honest account—or was she always crafting her journals knowing that a third party might read it? So when you ask whether I think my maps are documentary or dramatization or adaptation, I guess my answer is “all of the above.”

The difference between the maps and the nonfiction graphic novels I’ve worked on is that I’m fully aware that the maps don’t tell the whole story, so my aim is that they’ll be entertaining enough to inspire someone to go to the library or bookstore to get the whole story. Conversely, we aim to tell the whole story—or as much of it as we can—with the graphic novels. Jim Ottaviani is probably the best known and most highly acclaimed nonfiction graphic novel writer working today, and Zander and I are thrilled to have illustrated two of his books, Bone Sharps, Cowboys, and Thunder Lizards (the story of Cope and Marsh, America’s first feuding paleontologists) and T-Minus: The Race to the Moon (the story of the US/Soviet space race, with a balanced look at both sides). I don’t know a ton about Jim’s writing habits, but it’s my impression that he produces his scripts with an academic eye, using as many sources as he’s able to, and writing a narrative that is as objective as he can make it. In Bone Sharps, for example, he has to stretch the truth a bit to make it a compelling narrative, but he acknowledges that by disclosing all of these factual errors and omissions in a big “fact vs. fiction” section at the end of the book. Other books that we’ve done, which touch on subjects like evolution, genetics, and rhetoric, are all heavily vetted. Currently we’re both writing and illustrating a graphic novel introduction to philosophy. And when I say “writing” I mean we’re crafting a sometimes-humorous narrative around philosophical content provided by a professor of philosophy, so the hard part has basically been done for us.

What’s on the horizon for you? You must get inundated with interesting content while working on The Appendix—do you ever come across something that screams out to be a longer book? Something on rocket cats, perhaps? Or does writing a published book, with all of its limitations and people looking over your shoulder, look less attractive now that you have a vehicle like The Appendix?

CHRIS I will get on writing that sitcom posthaste.

We run across great things every day at The Appendix, and many of the pieces we the editors write are pulling from long, long-standing interests. (Rocket cats are very much Ben’s, for example!) Right now the majority of my writing time is consumed by my dissertation, a long history of grave-opening in Peru. Pieces of it may end up in The Appendix as an article or two, but I’m mostly trying to save that for a possible eventual book. The other book I keep tapping at is the Death of a Sailor serialization I’ve shared with the journal. There have been three chapters so far, and it’s paused, for the moment, while I wrap other things up. (It may be paused for a year or more, given that the next wave of research I have to do on it might need travel to Portugal, Brazil, and London. Which will be fun, I’m sure, but something else will have to pay for that.)

Speaking of travel, how’s this for a last set of questions: where would you most like to travel, why, and with whom? And when, chronology being no limit? And maybe as a preface: you’ve done so much interesting stuff with Canada’s frozen north. Have you been there? If so, what was that like?

KEVIN I’d like to visit the polar regions some day, but it’s the getting there that interests me more than the place itself. My ideal trip would be as a deckhand on a sailing ship headed north, or maybe as a cartographer helping to chart the Canadian islands on Otto Sverdrup’s Fram voyage a hundred years ago. There’s something incredibly romantic about sailing north without knowing what was up there. Rumors used to abound about a warm open polar sea or even a hole at the North Pole that led straight to the center of the Earth. On the flipside, scurvy doesn’t sound like much fun, so an ideal trip would be AFTER scurvy had been figured out, but BEFORE everything up north had been all mapped out.

I’ve never been to the Canadian Arctic before, but during college my friend and I spent a week in Alaska, biking around Anchorage and kayaking in Prince William Sound. We didn’t see any icebergs but we definitely got a taste of what it’s like to be alone in a vast, cold environment. Part of me longs to go on another adventure like that, but another part of me is happy to do my traveling through books and Google Maps, where I don’t risk losing my fingers to frostbite.